Prevention of Dental Disease

Fluoride Administration

Dietary Fluoride Supplementation

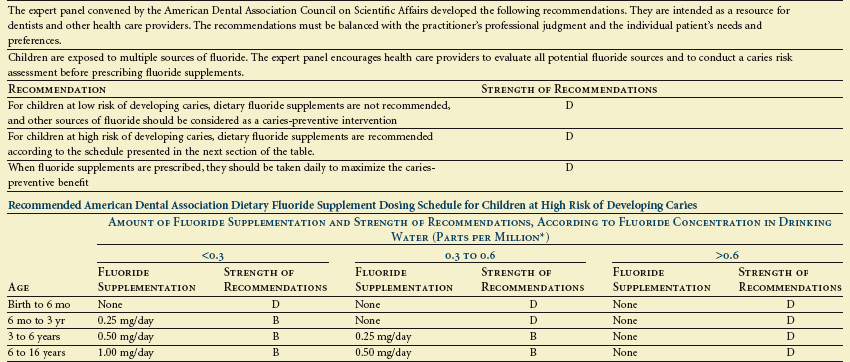

Recommendations on the prescription of dietary fluoride supplementation for caries prevention were modified in 2010.1 Dietary fluoride supplementation should be prescribed only for children who are at high risk of developing caries and whose primary source of drinking water is deficient in fluoride. Therefore the first step for the clinician is to determine if the child is at high risk as described in Chapters 13 and 14. If the child is at high risk and drinks water that is deficient in fluoride, then fluoride supplementation should be considered (Table 19-1).

TABLE 19-1

TABLE 19-1

Clinical Recommendations for the Use of Dietary Fluoride Supplements

*1.0 part per million = 1 milligram per liter.

From Rozier RG, Adair S, Graham F et al: Evidence-based clinical recommendations on the prescription of dietary fluoride supplements for caries prevention. A report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs, J Am Dent Assoc 141(12):1480–1489, 2010.

Professional Applications OF Fluoride

Topical application of highly concentrated forms of fluoride has been provided in clinical settings for many years. The most commonly used agents include 8% to 10% solutions of stannous fluoride as well as 2% sodium fluoride and 1.23% acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF); the latter two compounds are available in solution, gel, and foam formulations. Numerous studies conducted before 1980 reported caries reductions averaging approximately 30% following use of these agents.2,3 However, several studies, including a large-scale national demonstration program4 have reported a more limited effect from semiannual applications of these agents (i.e., caries reductions of roughly 25%), especially in areas with fluoridated water.5 Fluoride varnish (Figure 19-1) has become a popular topical agent for preschool children and children with special health care needs, and it has been recommended for conditions in which decalcified enamel secondary to poor plaque removal or poor feeding practices is present.6–8

Cost-Benefit Considerations

In a private practice setting the patient’s willingness or ability to pay for different forms of treatment usually is an important factor in determining what types of services are provided. In the case of public programs or private third-party payors, the decision to provide reimbursement for various services may be based on a more formal analysis of the relationship between the costs and benefits associated with those services. The ratio of costs to benefits has historically been higher for topical fluoride applications provided in dental offices than for other types of preventive services or for the same services provided in other settings. Consequently, professional topical fluoride treatments have not been recommended as a public health measure because of their unfavorable cost/benefit ratio. Documented changes in caries levels and patterns of decay in children in the United States have pushed these ratios even higher. Studies have reported that a substantial proportion of school-aged children in the United States are caries free and that a relatively small percentage of children account for a large percentage of all tooth decay.9 In addition to the overall decline in the level of caries, there has been a decrease in the proportion of smooth-surface caries and a corresponding increase in the proportion of pit and fissure caries. The combination of these factors seems to be associated with a reduction in the effectiveness of concentrated topical fluoride therapy in terms of the actual number of surfaces saved from becoming carious during a given period.3

A factor that has been repeatedly demonstrated to be associated with a reduction in both the risk of developing caries and the relative effectiveness of topical fluoride therapy is the availability of drinking water containing fluoride. Studies have shown that topical fluorides are considerably more effective in reducing the incidence of decay in nonfluoridated areas compared with fluoridated areas.5 Therefore, the cost of preventing a carious lesion in a fluoridated area by means of professional topical fluoride therapy is significantly greater than the cost of preventing a lesion in a non-fluoridated area. From a cost-benefit perspective, this suggests that in fluoridated areas topical fluoride treatments should be reserved for patients who have a history of moderate to high caries development or who are in proven high-risk categories. Those who do not seem to be particularly prone to developing caries, especially smooth-surface decay, would probably benefit more from other forms of prevention such as occlusal sealants.

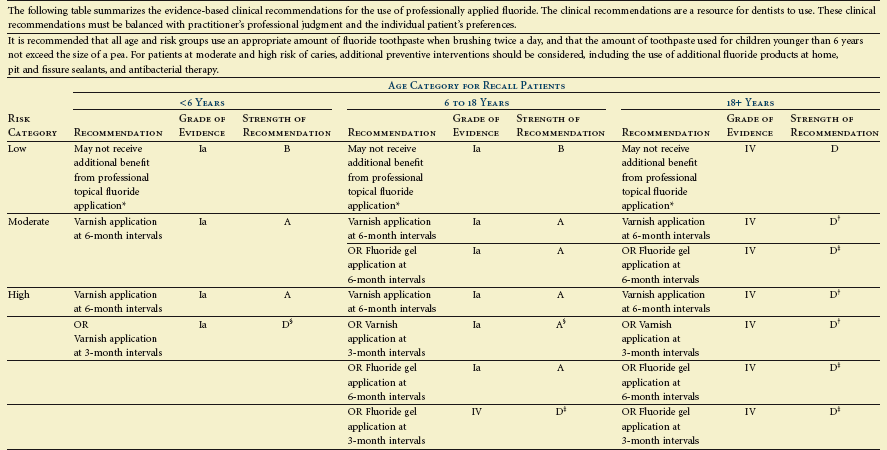

Presently the recommendations for professionally applied topical fluoride are that children 3 to 6 years old at moderate risk should receive topical fluoride applications every 6 months. Those children with high caries risk should receive the treatments more frequently (i.e., every 3 to 6 months)10 (Table 19-2).

TABLE 19-2

TABLE 19-2

Evidenced-Based Clinical Recommendations for Professionally Applied Topical Fluoride

*Fluoridated water and fluoride toothpastes may provide adequate caries prevention in this risk category. Whether or not to apply topical fluoride in such cases is a decision that should balance this consideration with the practitioner’s professional judgment and the individual patient’s preferences.

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline

FIGURE 19-1

FIGURE 19-1