Diseases of the Skin

Ectodermal Dysplasia: (Hereditary ectodermal dysplasia, ectodermal dysplasia syndrome)

Etiology

Ectodermal dysplasia syndrome results from aberrant development of ectodermal derivatives in early embryonic life. Genes responsible for the varied syndromes are located on different chromosomes and may be mutated or deleted.

Oral Manifestations

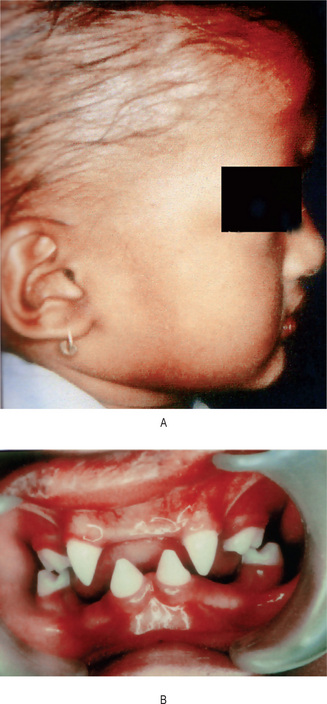

The oral findings are of particular interest, since patients with this abnormality invariably manifest anodontia or oligodontia, complete or partial absence of teeth, with frequent malformation of any teeth present, both deciduous and permanent dentitions (Fig. 19-1B and C). Where some teeth are present, they are commonly truncated or cone shaped. It should be pointed out that even when complete anodontia exists, the growth of the jaw is not impaired. This would imply that the development of the jaws, except for the alveolar process, is not dependent upon the presence of teeth. However, since the alveolar process does not develop in the absence of teeth, there is a reduction from the normal vertical dimension resulting in the protuberant lips. In addition, the palatal arch is frequently high and a cleft palate may be present (Fig. 19-2).

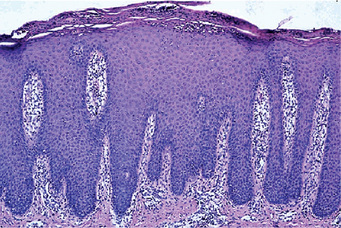

Figure 19-1 Hereditary ectodermal dysplasia.

(A)The protuberant lips, the thin, scanty hair and the saddle-nose are characteristic of the disease. (B) The teeth are cone-shaped. (C) Radiographs showing congenitally missing teeth Courtesy of Dr Ralph E McDonald.

Chondroectodermal Dysplasia: (Ellis-van Creveld syndrome)

Oral Lichen Planus: (Lichen ruber planus)

Etiology

An interesting association of lichen planus, diabetes mellitus and vascular hypertension has been described by Grinspan, the triad being described as Grinspan’s syndrome by Grupper. However, the reported associations between OLP and systemic diseases may be coincidental, because OLP is relatively common, it occurs predominantly in older adults, and many drugs used in the treatment of systemic diseases trigger the development of oral lichenoid lesions as an adverse effect.

Oral Manifestations

Shklar and McCarthy have reported the following distribution of oral lesions: buccal mucosa, 80%; tongue, 65%; lips, 20%; gingiva, floor of mouth and palate, less than 10% (Fig. 19-3). These oral lesions produce no significant symptoms, although occasionally patients will complain of a burning sensation in the involved areas.

Figure 19-3 Oral lichen planus.

Plaque-like oral lichen planus on the buccal mucosa on the left side.

Vesicle and bulla formation has been reported in oral lesions of lichen planus, but this is not a common finding, and the diagnosis of lichen planus from the clinical appearance of the lesions is extremely difficult. This bullous form of lichen planus has been discussed by Shklar and Andreasen. Still another type, the so-called erosive form of lichen planus, usually begins as such and not as a progressive process from ‘nonerosive’ lichen planus. Nevertheless the vesicular or bullous form of the disease may clinically resemble erosive lichen planus when the vesicles rupture. Eroded or frankly ulcerated lesions are irregular in size and shape and appear as raw, painful areas in the same general sites involved by the simple or reticular form of the disease (Fig. 19-4). Despite the erosion of the mucosa, the characteristic radiating striae may often be noted on the periphery of the individual lesions.

A hypertrophic form of lichen planus may also occur on the oral mucosa, generally appearing as a well-circumscribed, elevated white lesion resembling leukoplakia. In such cases biopsy is usually necessary to establish the diagnosis.

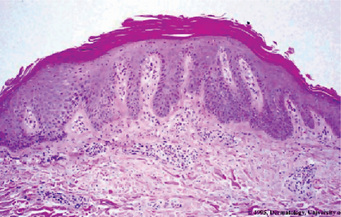

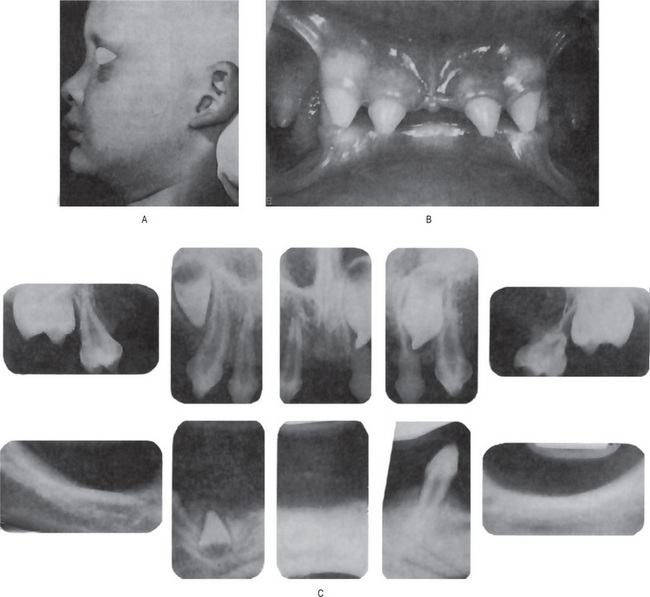

Histologic Findings

Degeneration of the basal keratinocytes and disruption of the anchoring elements of the epithelial basement membrane and basal keratinocytes (e.g. hemidesmosomes, filaments, fibrils) weakens the epithelial-connective tissue interface. As a result, histologic clefts (i.e. Max-Joseph spaces) may form, and blisters on the oral mucosa (bullous lichen planus) may be seen at clinical examination. B cells and plasma cells are uncommon findings (Fig. 19-5).

Figure 19-5 Oral lichen planus.

(A) Note the basilar degeneration and band-like infiltration of inflammatory cells in the subepithelial zone. (B) Histopathology of lichenoid mucositis (H and E x 100). Note the diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells involving parts of submucosa. (C) Photomicrograph of Langerhans cells in lichen planus (Gold Chloride staining x400). (D) Photomicrograph of Langerhans cells in lichenoid mucositis (Gold Chloride staining x400) Courtesy of the Dept of Oral Pathology, Ragas Dental College and Hospital, Chennai.

In OLP, electron microscopy is used principally as a research tool. The ultrastructure of the colloid bodies suggests that they are apoptotic keratinocytes, and recent studies of the endlabeling method revealed DNA fragmentation in these cells. Electron microscopy shows breaks, branches, and duplications of the basement membrane in OLP.

Treatment

At present there is no cure, although various agents have been tried. Due to its minimal potential for malignant transformation, these patients used to be kept on longterm follow-up. Medical treatment of OLP is essential for the management of painful, erythematous, erosive, or bullous lesions. The principal aims of current OLP therapy are the resolution of painful symptoms, the resolution of oral mucosal lesions, the reduction of the risk of oral cancer, and the maintenance of good oral hygiene. As it is an autoimmune mediated condition, corticosteroids are recommended. In patients with recurrent painful disease, another goal is the prolongation of their symptom free intervals. The main concerns with the current therapies are the local and systemic adverse effects and lesion recurrence after treatment is withdrawn. Patients should be observed periodically, particularly those with the erosive or atrophic forms and those who also have a history of alcohol and tobacco misuse, because of the risk of malignant transformation.

Psoriasis

Etiology

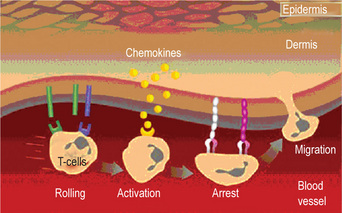

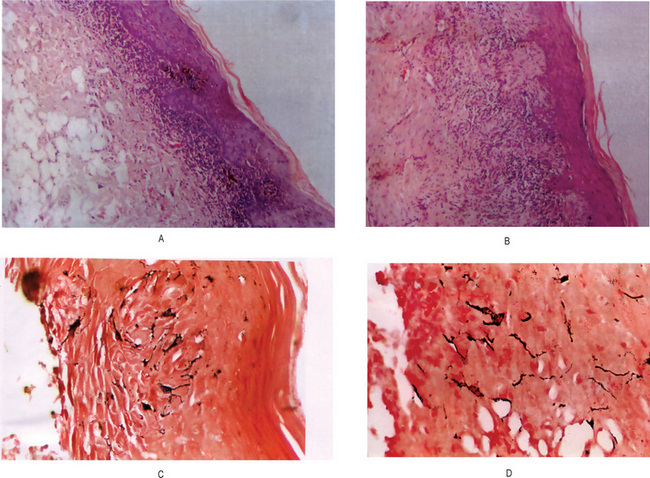

The cause of psoriasis is unknown. Patients do have a genetic predisposition for the disease; the disease has a strong association with HLA Cw6 and B57 region. Recent evidence suggests that in addition to these regions many other gene loci such as 19p13, 17q25, and 1q21 may also increase the susceptibility to this disease. The trigger event may be unknown in most cases but is likely to be an immunologic event. Significant evidence is accumulating that psoriasis is an autoimmune disease. Lesions of psoriasis are associated with increased activity of T-cells in underlying skin. Also of significance is that 2.5% of persons with HIV develop psoriasis during the course of the disease. Perceived stress can cause exacerbation of psoriasis. Some authors suggest that psoriasis is a stress-related disease and offer findings of increased concentrations of neurotransmitters in psoriatic plaques. The pathogenesis of psoriatic lesions is due to an increase in the turnover rate of dermal cells, from the normal turnover duration of 23 days to three to five days in affected areas (Fig. 19-6). As would be expected, there is also a dramatic increase in the mitotic index of psoriatic skin which is said to even surpass that of epidermoid carcinoma.

Oral Manifestations

Such lesions have been reported on the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, gingiva and floor of the mouth (Fig. 19-7). Clinically, they are described as gray or yellowish-white plaques; as silvery white, scaly lesions with an erythematous base; as multiple papular eruptions which may be ulcerated; or as small, papillary, elevated lesions with a scaly surface. Reports by Goldman and Bloom and by Levin emphasized the vagaries in the clinical appearance of oral psoriasis. Psoriasis of the gingiva was reported by Brayshaw and Orban and that of the alveolar ridge by Wooten and his associates in patients without skin lesions; however, cases of mucosal involvement without skin manifestations must be viewed with caution even though the histologic sections of the lesions do present a psoriasiform pattern. White and his associates have reviewed the literature on intraoral psoriasis while reporting an additional case. Fischman and his coworkers studied an oral lesion in a patient with skin lesions of psoriasis utilizing light and electron microscopy, as well as immunologic methods, and noted in all instances that the findings in the oral lesion were similar to those in the skin lesions. They concluded that true oral lesions do occur in psoriasis.

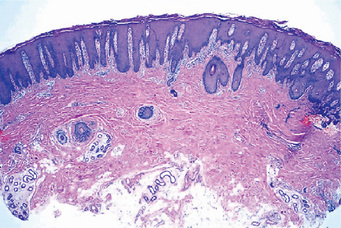

Histologic Features

The microscopic appearance of psoriasis is characterized by uniform parakeratosis, absence of the stratum granulosum and elongation and clubbing of the rete pegs (Figs. 19-8, 19-9). The epithelium over the connective tissue papillae is thinned, and it is from these points that bleeding occurs when the scales are peeled off. Tortuous, dilated capillaries extending high in the papillae are prominent. Intraepithelial microabscesses (Monro’s abscesses) are a common but not invariable finding; they are reported by Pisanty and Ship to be absent in oral psoriasis (Fig. 19-10). Mild lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltration of the connective tissue is also typical, particularly perivascular and periadnexal in location.

Pityriasis Rosea

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a common benign papulosquamous disease causing acute skin eruption of unknown etiology. Pityriasis denotes fine scales, and rosea implies rose-colored or pink. It can have a number of clinical manifestations and its diagnosis is important because it may resemble secondary syphilis.

Erythema Multiforme: (Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme major, erythema multiforme minor, herpes-induced EM major, herpes-associated erythema multiforme, drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome)

Etiology

Many suspected etiologic factors have been reported to cause EM. EM and SJS are both caused by drugs, but infectious agents are considered to be the major cause of EM. Today, EM minor is regarded as being triggered by HSV in nearly 100% of cases; many instances of idiopathic EM minor may be precipitated by subclinical HSV infection. A herpetic etiology also accounts for 55% of cases of EM major. Among the other infections, Mycoplasma infection appears to be a common cause. Drugs are reported in many documented cases of SJS and EM major. Sulfa drugs are the most common triggers.

Clinical Features

Erythema multiforme occurs chiefly in young adults, although it may develop at any age, the highest incidence is in the second to fourth decades of life and affects males more frequently than females. This disease is characterized by the occurrence of asymptomatic, vividly erythematous discrete macules, papules or occasionally vesicles and bullae distributed in a rather symmetrical pattern most commonly over the hands and arms, feet and legs, face and neck. The individual lesions may vary considerably in size even in the same patient, but are generally only a few centimeters or less in diameter. A concentric ringlike appearance of the lesions, resulting from the varying shades of erythema, occurs in some cases and has given rise to the terms ‘target’, ‘iris’, or ‘bull’s eye’ in describing them (Fig. 19-11). They are most common on the hands, wrists and ankles. Mucous membrane involvement, including the oral cavity, is common. The lesions make their appearance rapidly, usually within a day or two, and persist from several days to a few weeks, gradually fading and eventually clearing. Recurrence of the disease over a period of years is common, however.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Pemphigus

. Pemphigus . Bullous Pemphigoid

. Bullous Pemphigoid . Epidermolysis Bullosa

. Epidermolysis Bullosa . Dermatitis Herpetiformis

. Dermatitis Herpetiformis . Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

. Acrodermatitis Enteropathica . Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus . Systemic Sclerosis

. Systemic Sclerosis . Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome . Focal Dermal Hypoplasia Syndrome

. Focal Dermal Hypoplasia Syndrome . Solar Elastosis

. Solar Elastosis