Chapter 18

Problem-Solving Challenges That Require Periradicular Surgical Intervention

Problem-solving challenges requiring periradicular surgical considerations addressed in this chapter are:

“The successful management of perforative defects is dependent not only on the etiology of the perforation, but also on the early diagnosis of the defect, choice of treatment, materials used, host response and practitioner expertise.”

Periapical surgery (see < ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

There are two general approaches to problem solving the treatment of lesions or defects on root surfaces below the attachment. The first is aimed at the repair of defects on the root surfaces, with the nature of the defect and its location being of major importance. The surgical techniques advocated are modifications of the periapical surgical procedures discussed in

Surgical Management of Problems Associated With Lateral Canals

The clinical incidence of problems associated with natural lateral canals does not rise to the statistical percentage of roots that actually have anatomically demonstrable lateral canals.

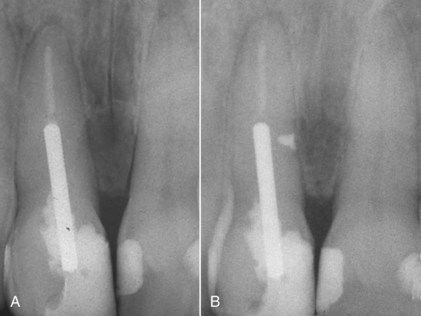

FIGURE 18-1 A, Preoperative radiograph of an endodontically treated mandibular premolar with a lateral canal lesion. B, One-year reevaluation radiograph showing resolution of the lateral lesion.

(Courtesy Dr. Ryan Wynne.)

FIGURE 18-2 Postoperative image showing extrusion of the filling materials and/or sealer through the lateral canal.

There are relatively few teeth with lateral lesions that fail to heal after root canal treatment. Even fewer are those which develop lateral lesions after root canal treatment.

FIGURE 18-3 Amalgam repair of a lateral canal communicating with an unfilled canal space between the root canal filling material and the post. Case was treated in 1976.

In the preoperative evaluation, determining the location of the lateral canal is a diagnostic challenge. Lateral canals can occur on any surface of the root and are rarely visible radiographically.

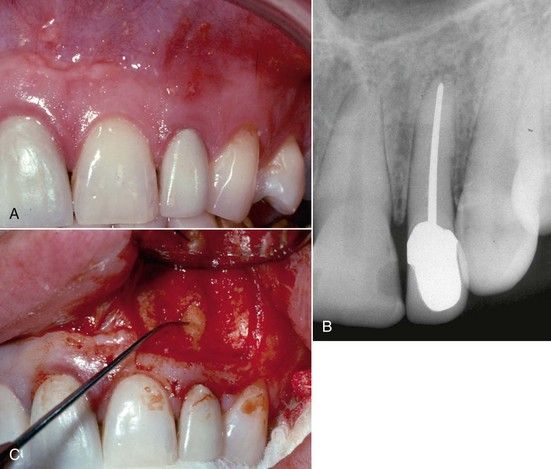

FIGURE 18-4 A, Clinical view of a sinus tract found on the labial aspect of the maxillary left lateral incisor. B, No radiolucency is visible in this area. C, Surgical exploration reveals a midroot lateral canal on the labial surface.

The presence of most lateral canals is inferred by the presence of a lateral radiolucency, which is only a two-dimensional representation of a dynamic three-dimensional process (

FIGURE 18-5 Messal bony lesion associated with a lateral canal presumably due to coronal leakage from recurrent caries.

A second anatomic problem is the surgical accessibility of the canal in interproximal or interradicular spaces. Lateral canals occurring in fluting of molar roots can be impossible to see at surgery, although some may be large enough to locate tactilely with an explorer. Even if they can be located, space limitations can prevent successful completion of the repair. The only avenue for possible resolution of these dilemmas is surgical exploration. Preoperatively, the patient should be informed that if the lateral canal is not accessible, the root may have to be removed in its entirety or the tooth may have to be extracted (

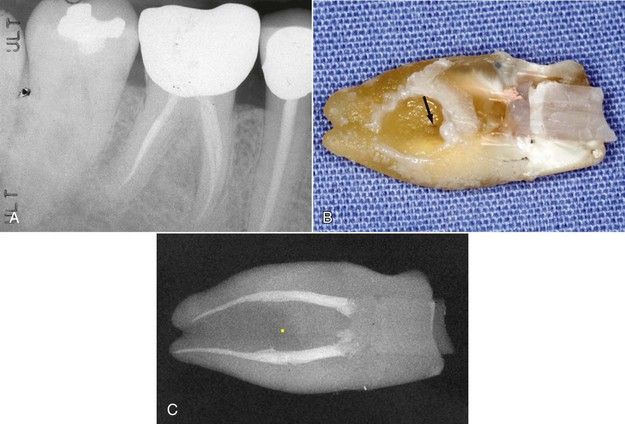

FIGURE 18-6 A, Lateral canal lesion located on the distal aspect of the mesial root of the mandibular right first molar. B, Extracted mesial root. Surgical repair was attempted, but it was not possible to visualize the lateral canal, owing to deep fluting of root surface. Note lateral canal (arrow). C, A radiograph of the root. Note the distance of the lateral canal (yellow dot) from the treated canals. Revision would have had no effect on this problem.

The essential elements of the surgical procedure are the same as for periapical surgery, which is described in detail in

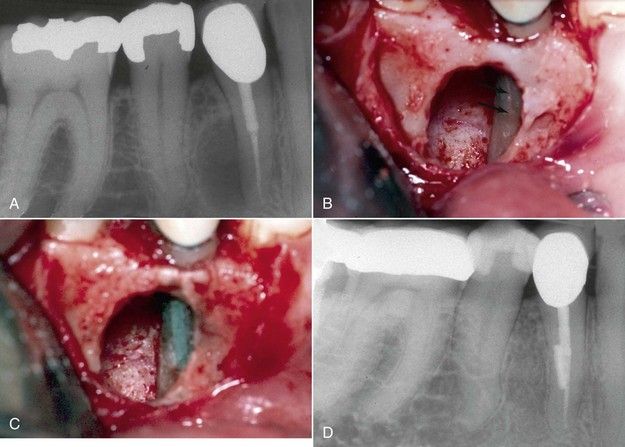

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 47-year-old male presented with a draining sinus tract on the midline of the labial papilla adjacent to the maxillary right central incisor. The lesion was difficult to discern radiographically (

Solution

Because of the presence of a post in the root and the absence of any periapical pathosis, the midroot area was exposed surgically, and the presence of a lateral canal was confirmed and repaired. A 9-year, 3-month reevaluation radiograph indicated excellent healing with restoration of the periodontal ligament space and lamina dura in the surgical site (see

As described for apical surgery in

Surgical Repair of Root Perforations Below the Attachment

Most perforations during access opening occur in the marginal periodontium (see

FIGURE 18-8 A, Furcal bone loss associated with an access perforation through the floor of the furcation. B, Calcium hydroxide used as a temporary seal during completion of the endodontic treatment. C, Reevaluation after 1 year. The perforation was permanently sealed with mineral trioxide aggregate. Note the restoration of normal bone architecture in the furcation.

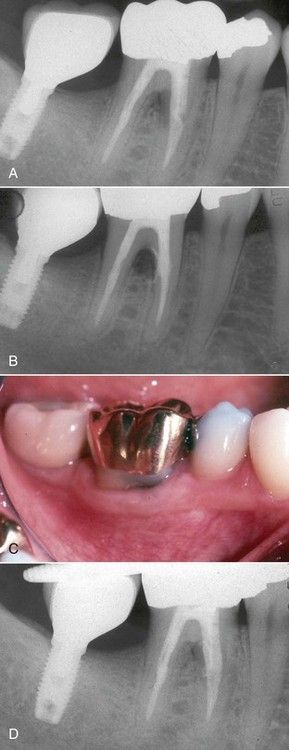

Larger perforations in the furcation can be problematic. If significant portions of the floor of the pulp chamber have been removed, the chance of successful repair is poor (![]() years, a furcation radiolucency lesion had developed, and a surgical repair was attempted. One year later, the bone had not healed completely. Although the patient was symptom free and the tooth functional, the prognosis was guarded.

years, a furcation radiolucency lesion had developed, and a surgical repair was attempted. One year later, the bone had not healed completely. Although the patient was symptom free and the tooth functional, the prognosis was guarded.

FIGURE 18-9 Extrusion of cement repair material through a furcation perforation. Chronic drainage through the gingival sulcus was apparent at the time of examination. Extraction was recommended.

FIGURE 18-10 A, Referral radiograph of mandibular left first molar. The furcation was perforated in the access procedure and was temporarily repaired with calcium hydroxide (arrows). B, Root canal treatment completed and perforation filled with mineral trioxide aggregate. It was a challenge to pack the material and not have extrusion. C, Reevaluation radiograph after ![]() years. Probings were normal but tooth was symptomatic, and the tooth had a sinus tract on the buccal mucosa. D, Surgical repair in progress. Note the intact crestal bone over the furcation. E, Fifteen-month reevaluation. Patient was asymptomatic, sinus tract had not reappeared, but prognosis was guarded.

years. Probings were normal but tooth was symptomatic, and the tooth had a sinus tract on the buccal mucosa. D, Surgical repair in progress. Note the intact crestal bone over the furcation. E, Fifteen-month reevaluation. Patient was asymptomatic, sinus tract had not reappeared, but prognosis was guarded.

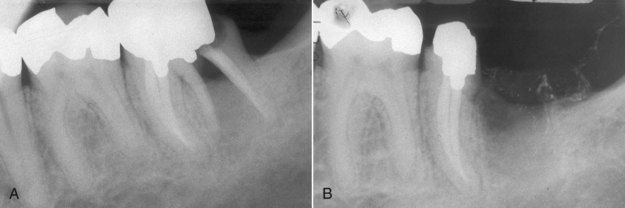

Lateral strip perforations can occur during root canal cleaning and shaping, generally with hand instruments or excessive use of large nickel-titanium instruments (see

FIGURE 18-11 Routine access and orifice-widening procedures on extracted tooth with a deeply fluted mesial root. A strip perforation quickly occurred that appeared to be unavoidable in a clinical case.

As with lesions adjacent to lateral canals, accessibility to the defect can be a major problem for repair, but these defects are usually larger and much easier to locate. If the defect is visible, the repair can be made in the same manner as with the repair of defects from lateral canals. Often the preparation must be longer vertically because of the thin dentin above and below the perforation itself (

FIGURE 18-12 A, Lateral lesion associated with a strip perforation. Probings are normal. B, Radiograph of repair with mineral trioxide aggregate. C, One-year reevaluation film showing restoration of normal periodontium on the buccal. Probings were normal. D, One-year reevaluation radiograph indicating bone healing in the furcation.

Strip perforations can also occur from excessive enlargement of the canal during post space preparation.

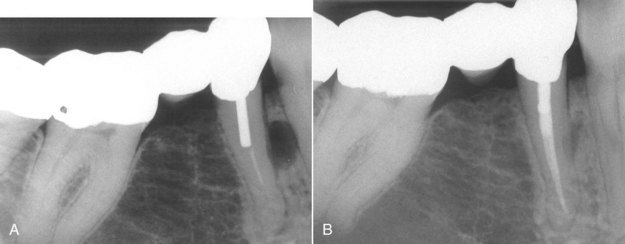

FIGURE 18-13 A, Lateral lesion associated with a stripping perforation due to overenlargement of the canal for post preparation. B, Five-month reevaluation indicating healing of the lesion.

FIGURE 18-14 A, Intraradicular post protruding through a perforation. B, Removal of the post is preferred, rather than attempting to cut the post back into the root prior to repairing the perforation.

Perforations with endodontic instruments can occur deep in the root from failure to negotiate curves, attempting to bypass blockages, or failing to consider the normal anatomy of the tooth during cleaning and shaping procedures. If discovered early, internal repairs may effectively resolve the perforation problem; if not possible, then surgery will probably be necessary.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 38-year-old female presented with what was considered to be a failing root canal procedure on a maxillary right central incisor (

FIGURE 18-15 A, Root-treated maxillary right central incisor with a large apical lesion. B, Instrument in perforation. The perforation was repaired with mineral trioxide aggregate. C, One-year reevaluation. Note that the post space was not used in placement of crown. This presents a long-term liability for continued success of the repair.

Solution

The tooth was reopened, and while the existing filling material was being removed, the patient felt pain at a level well short of the estimated tooth length. An instrument was placed, and a radiograph was made. A labial perforation was revealed that proved to be the etiology of all the current pathosis (

Surgical Repair of Problems Associated With Some Root Fractures

The etiology of partial root fractures on the lateral root surface of some teeth is unknown. Clinical findings are typical of lesions associated with lateral canals or strip perforations along with normal periodontal probings. Often the signs of acute or chronic inflammation/infection (midroot swelling, sinus tracts, etc.) are present.

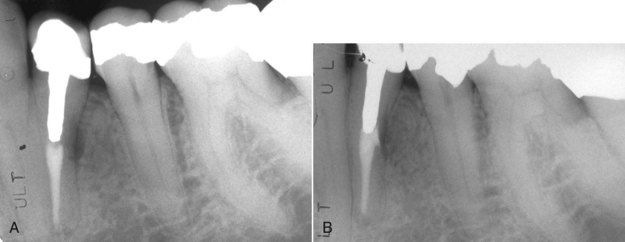

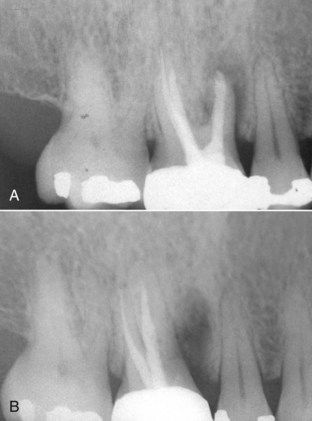

Radiographic findings are similarly nonspecific. The radiolucency is characterized by an apical and a coronal border. In these cases, the apex is usually not involved (see

FIGURE 18-16 A, Preoperative radiograph of a large radiolucent lesion assumed to be associated with a lateral canal on the treated second premolar. B, Fracture line (arrows) located on palatal surface. Tooth was extracted due to inaccessibility.

If the fracture line is in a position where repair is possible, the techniques for lateral repairs will be effective. The most significant and difficult modification is the preparation that must follow the crack line to its full extent. The result is a narrow slot preparation similar to the preparation of an isthmus between two canal orifices in periapical surgery.

If straight-line access is possible, a quarter-round (0.5 mm) bur is ideal. For maximum control, the straight, low-speed handpiece, held in the pencil grip, works well. If straight-line access is not possible, the ultrasonic instrument can be used with either a small, angled apical surgery tip or an endodontic file that has been shortened to increase stiffness and placed in a special ultrasonic adaptor.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

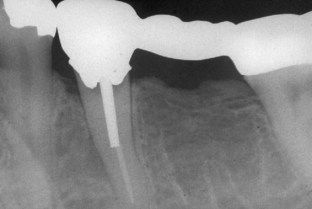

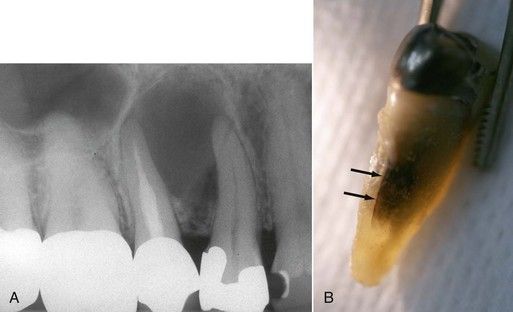

A 40-year-old patient presented with a swelling in the midroot area of the mandibular left second premolar. The tooth had a previous root canal procedure and was restored with a post and crown. Radiographically, a large midroot radiolucency was present, and a large uncleaned lateral canal was suspected (

FIGURE 18-17 A, Preoperative radiograph of a lateral radiolucency assumed to be associated with a lateral canal on the treated first premolar. B, Surgical exposure reveals a vertical midroot fracture line (arrows). C, Repair of the fracture line with MTA. D, Four-year reevaluation radiograph indicating excellent healing.

Solution

Nonsurgical revision was not considered and the defect was exposed surgically. Following curettage, a midroot fracture line was observed on the distal buccal aspect (see

Surgical Techniques for Resection of Roots and Teeth

General Considerations

Root resection, or root amputation, involves removing the root and either leaving the crown intact (

FIGURE 18-18 A, Maxillary first molar with a vertical fracture in the mesial-buccal root. B, Following root amputation of the fractured root.

Tooth resection, or hemisection, is a technique in which a tooth is “cut in half.”

FIGURE 18-21 A, Mandibular first molar with a vertical fracture in the distal root. B, Post root resection. This is one of the most common endodontic indications for tooth resection.

Performing root/tooth resections to allow retention of compromised teeth has been all but abandoned owing to the success of contemporary implants.

Multiple published studies in the periodontal literature have supported root resection as a successful long-term treatment.

Case Selection Criteria

Root resection (root amputation) and tooth resection (hemisection) procedures are useful solutions for a variety of clinical problems. From a periodontal standpoint, the most common indication is significant periodontal bone loss localized to one root, with adequate bone support for the adjacent roots. Additional periodontal indications are grade II or III horizontal furcation involvement, dehiscence/fenestration, invasive resorption, and adverse root proximity.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 58-year-old male presented for examination with palpation tenderness and dull pain in the area of the maxillary left first molar. A periapical radiograph indicated a large radiolucency over the apex of the mesial buccal root, suggesting periapical pathosis of pulpal origin, specifically associated with a necrotic pulp (

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses