CHAPTER 18

Implants in Orthodontics

As one of the oldest specialties in dentistry, orthodontics has seen several periods of radical transformation. New theories, new devices, and new ways of treatment have often dramatically changed the way orthodontists move teeth or jaws. From bracket development such as edgewise slots, bondable adhesives, ceramics, and self-ligating brackets to NiTi wires, coils, and rapid palatal expanders, all the way through LeFort osteotomies and distraction osteogenesis, the world of orthodontics is radically different from what the founding fathers might remember.

Orthodontics is once again poised for greater and more efficient treatment, less reliance on patient cooperation, and possibly even less need for surgical interventions. Temporary implantation of material to gain a mechanical advantage during orthodontic treatment will undoubtedly be one of the great transformers of orthodontics in the early portion of the 21st century. Knowledge of the history of implants as well as various implant types available to practitioners is critical in being able to provide patients with the best and most up-to-date technical materials available for orthodontic treatment with temporary implant anchors (TIAs).

1 What is the history of implants in dentistry?

The history of implantable material in the oral cavity goes back several millennia. There are reports of items such as seashells, precious stones, ivory, and bone being used as implants.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

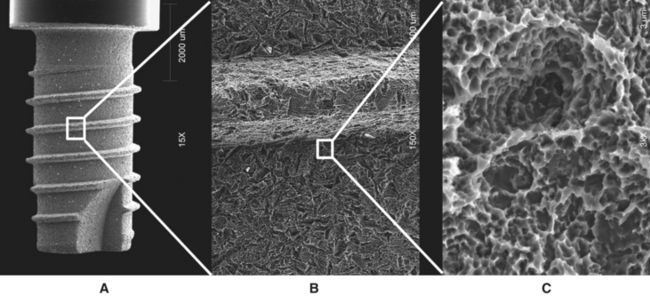

In the mid 1960s, P.I. Brånemark made famous the body’s ability to accept and bond to titanium, a process coined osseointegration.

2 What is the history of implants in orthodontics?

Attempts to use implants in orthodontic treatment can be traced back to the early 1900s

The first mention of implant osseous anchorage in the palate was by Triaca

3 Why would one consider implants for orthodontic treatment?

Implants are useful in orthodontic treatment for the very fact that orthodontists rely exclusively on anchorage to move teeth.

Force transfer is less than complete when the anchor teeth experience movement themselves.

BENEFITS OF IMPLANTS IN ORTHODONTICS

4 What are some of the advantages of using implants for orthodontic treatment?

5 What are some of the disadvantages of using implants for orthodontic treatment?

A disadvantage of using implants can be the cost, the procedure involved, and possible complications encountered. With all types of implants, cost should be addressed. When a surgeon’s office is placing an implant, there is usually a fee for placement as well as for removal. This fee will vary depending on the cost of the materials as well as the variation in location. Even if an implant is to be placed by the orthodontist, a fee may still be considered necessary for financial as well as for procedural purposes.

The procedure, although often espoused to be “minor,” should still be thought of as a surgical procedure. Nonsurgical correction of patients traditionally considered surgical patients is promising but has not been verified with adequate long-term results; thus, the ability to maintain the end treatment result is not completely confirmed. Finally, the complications that may arise from placing an implant into a tooth or with the movement of a tooth into an implant would be less than desirable. Complications with every device an orthodontist uses should always be considered a disadvantage.

6 What are some of the considerations in regard to specific treatment mechanics?

When any orthodontic implant is used, force vectors need to be appropriately applied and delivered.

If the maxillary anterior teeth exhibit a shallow or negative vertical overlap (open bite tendency), retraction from a mini-implant placed closer to the gingival margin of the teeth would be appropriate, as would the attachment of the retraction force to a hook extending a distance off the wire. This would place the retraction force higher into the vestibule and thus retract in a more horizontal vector to help correct the open bite. With palatal implants, the teeth themselves can either be moved with the use of activation from the implant or locked down as anchors to move adjacent teeth with traditional mechanics.

7 How can implants benefit orthodontics beyond traditional mechanics?

Implants may release some of the constraints that Newton’s Third Law holds on the orthodontist when working with tooth-borne anchorage. Of course, Newton’s Third Law still applies, but the resultant force on the implant releases the other teeth from force application and hence movement. Newton’s First Law gains greater importance in that teeth that are not “in motion” will likely stay put. Depending on the implant system and mechanics, a greater expression of the force applied results in more accurate torque control and movement of the teeth to be moved.

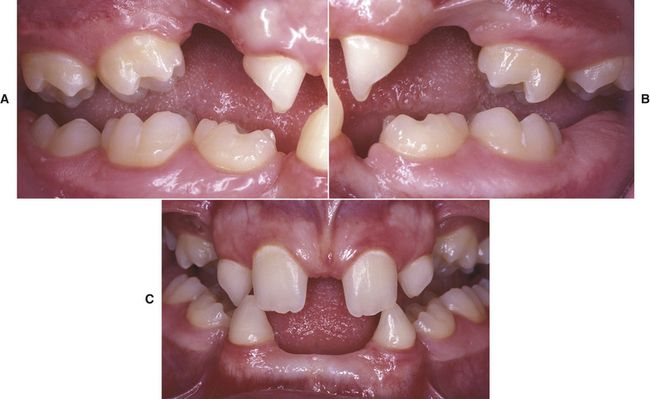

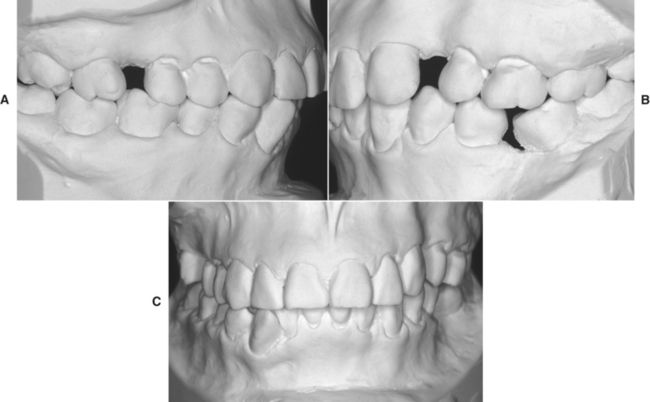

Implants also allow the orthodontist to treat patients who may have an inadequate number of teeth to act as anchors (

FIG 18-2 A-C, Adult patient with compromised maxillary and mandibular dentition caused by long-standing loss of teeth, supereruption, crowding, midline shifts, and angulation problems.

8 Should we consider implants in more orthodontic treatments?

Whether or not an individual practitioner decides to consider implants as an option in treatment plans that are “more routine” is entirely up to the practitioner’s desire. If implants can aid treatment, decrease morbidity of teeth, and increase the effectiveness of the bracket system, then most certainly they should be considered for use in any complex treatments that are not being featured on an “extreme makeover” edition.

One might argue that using implants is too invasive to consider using for routine application because of the surgical procedure. Many practitioners could counter that the use of a transpalatal arch (TPA) and headgear is much more invasive, certainly more taxing on the patient, and obviously affecting the patient in a far greater way than the placement of some form of temporary implant. Where the line is drawn should not be relative to the perceived “invasiveness” or a claimed “extraneous” application of dental materials.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses