Periodontal Maintenance and Prevention

Gwen Essex, Based on the original work by

and Mari-Anne L. Low

• Explain the effectiveness of periodontal maintenance therapy in the prevention of disease, disease progression, and tooth loss.

• Describe the elements of a successful maintenance program.

• State five major objectives of periodontal maintenance.

• Define the importance of patient compliance.

• Describe strategies to improve compliance with recommended maintenance intervals and oral hygiene regimens.

• List the principal aims and components of the maintenance appointment.

• Recognize the signs of recurrent periodontitis and assess the factors that contribute to its development.

• Describe the causes of root surface caries and therapeutic approaches to prevent development of this common problem.

• Explain the theory, causes, and management of dentin sensitivity.

Preventing recurrent disease and maintaining oral health are of fundamental importance for the success of periodontal therapy. Chronic gingival inflammation can resolve if the local etiologic factors are removed during the active phase of periodontal treatment. However, the long-term stability of results and the prevention of recurring disease require regular supervision in an effective periodontal maintenance program. Periodontal maintenance is “the continuing periodic assessment and prophylactic treatment of the periodontal structures that permit early detection and treatment of new or recurring abnormalities or disease,”1 commonly referred to as recall, periodontal maintenance therapy, supportive periodontal therapy, or the maintenance phase of periodontal treatment.

• Effectiveness of periodontal therapy in arresting the progression of periodontitis and preventing tooth loss

• Objectives of periodontal maintenance

• Importance of patient compliance with recommended recall schedules and plaque biofilm control regimens

• Components of the maintenance appointment

• Recurrence of periodontal disease

• Significance of caries in the periodontal maintenance population and the appropriate use of fluorides in caries prevention

• Sensitivity of dentin after periodontal therapy and recommended treatment

Effectiveness of Periodontal Therapy

The major objective of periodontal therapy is to arrest the progression of periodontal disease by eliminating or reducing the local microbial etiologic factors—that is, removal of the pathogens that illicit the inflammatory response in the host. Overwhelming evidence shows the effectiveness of periodontal therapy in preventing disease, slowing the progression of disease, and minimizing tooth loss caused by the periodontal disease process. Many longitudinal studies show that periodontal therapy is effective in maintaining teeth in a state of health, function, and comfort for many years.2 In contrast, untreated periodontal disease progresses, with a continual loss of the periodontium over time.3 Ultimately, this chronic destruction is responsible for tooth mortality. Furthermore, the stability of results obtained through active periodontal therapy requires a regular maintenance program.

Prevention of Disease

Epidemiologic and clinical studies have provided strong evidence to correlate poor personal oral hygiene care and the presence of gingivitis. A landmark study by Löe and colleagues4 and Theilade and associates5 described heavy plaque biofilm accumulation and generalized mild gingivitis in patients with a normally healthy periodontium after 9 to 21 days without any personal oral hygiene. The observed experimental gingivitis was reversed when daily plaque biofilm control procedures were reinstituted. These results provide the foundation on which plaque biofilm control is based. To encourage and support the patient in maintaining a clean and healthy oral environment, the dental hygienist should emphasize the significance of personal oral hygiene and review appropriate plaque biofilm control techniques during each maintenance visit.

Gingivitis is associated with the occurrence of periodontal disease. Both human and laboratory animal studies have shown that gingivitis does not always proceed to periodontitis; however, periodontitis is always preceded by gingivitis.3 Therefore, the recognition and treatment of gingivitis are vital to the goals of maintenance therapy.

Both effective personal oral hygiene and professional maintenance therapy are critical to the prevention of periodontal disease. Despite their benefit in resolving gingivitis, daily oral hygiene procedures alone have limited effects on periodontal disease. Evidence suggests that supragingival plaque biofilm control alone can reduce inflammation associated with gingivitis; however, improvement in probing depths and clinical attachment from plaque biofilm control alone is minimal in patients with periodontitis.6 This limited clinical improvement may be a result of the unpredictable effect of supragingival plaque biofilm control in altering the subgingival microbiota in pocket depths greater than 5 mm. However, scaling and root planing have a significant effect on subgingival biota and probing depths.7–10 This observation reinforces the importance of professional subgingival mechanical instrumentation at regular intervals in conjunction with personal oral hygiene to maintain periodontal health.

Prevention of Disease Progression

The periodontal response after effective nonsurgical and surgical therapy favors the reestablishment and maintenance of periodontal health. Numerous studies have shown that removing supragingival and subgingival bacterial deposits can resolve inflammation and halt disease progression.6 In addition, significant advances in understanding the complex causes of periodontal disease and a wider selection of therapeutic modalities have contributed to successful periodontal treatment.

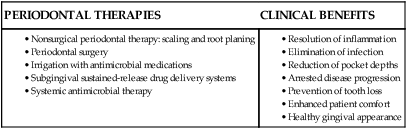

Commonly, several forms of therapy are combined to disrupt the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Current periodontal therapies and the clinical benefits provided are shown in Table 17-1.

Research has verified the effect of periodontal therapies on clinical parameters such as bleeding on probing, loss of clinical attachment, and changes in gingival color and form. For example, two longitudinal studies evaluated the effects of four types of periodontal therapy—coronal scaling, root planing, modified Widman surgery (flap surgery to provide access for scaling and root planing), and flap surgery with osseous resection—on the prevalence of bleeding on probing and suppuration.11,12 Both studies confirmed that all four therapies, followed by maintenance care at 3-month intervals, reduced the prevalence of these disease indicators. However, coronal scaling alone was less effective in sites with greater than 5-mm pocket depths. It may be that areas with increased probing depths continued to exhibit greater inflammation because adequate debridement was more difficult without surgical intervention. Maintenance care at 3-month intervals promoted the long-term results of all therapies.

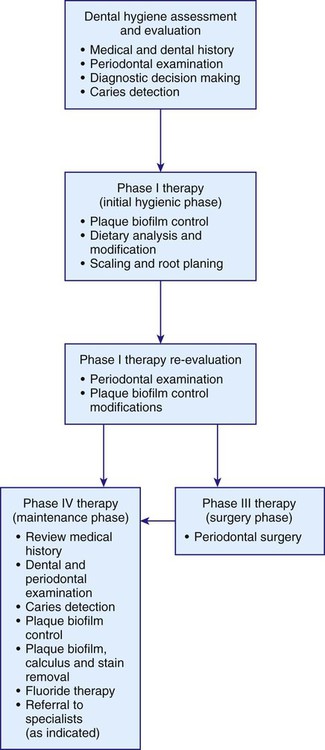

Nonsurgical periodontal therapy, also called Phase I therapy, or the hygienic phase, is recognized as an effective treatment to arrest or retard the progression of early periodontal disease. The American Academy of Periodontology defines nonsurgical periodontal treatment as the phase of periodontal therapy that includes plaque biofilm control, plaque biofilm removal, supragingival and subgingival scaling, root planing, and the use of chemical adjuncts.13 Several longitudinal studies confirmed the effectiveness of nonsurgical periodontal therapy for early intervention of periodontal disease when it is followed by regular maintenance visits.6 Research conducted in a patient group with moderate to advanced periodontal disease treated with oral hygiene instruction, scaling and root planing, and elimination of plaque biofilm retentive factors demonstrated the short-term effects of initial periodontal therapy. When examined 3 to 5 months after therapy, patients had reduced probing pocket depths and improved probing attachment levels.9

Regular periodontal maintenance is critical to the lasting success of both nonsurgical and surgical periodontal therapy. Numerous long-term studies have established the effectiveness of frequent maintenance care to halt or significantly reduce the rate of disease progression. Studies comparing patients who received maintenance care three to six times per year with patients who received maintenance care only once per year clearly showed the arrest of disease progression with frequent recall visits. Patients who underwent maintenance care visits only once per year showed gradual worsening of plaque biofilm and gingival indices, probing depths, and clinical attachment loss.14–16 Clearly, the benefits achieved by active periodontal therapy must be maintained by frequent maintenance care to prevent further deterioration of the periodontium.

Prevention of Tooth Loss

Many long-term studies have shown the effectiveness of periodontal therapy and maintenance care in reducing the number of teeth extracted because of end-stage periodontal destruction. Several researchers have documented tooth loss in longitudinal studies of individuals either receiving or not receiving periodontal treatment, including maintenance therapy.17,18 Tooth mortality rates in treated individuals ranged from 0.6 to 2.2 teeth lost over 10 years. By comparison, individuals with untreated periodontitis lost five to six teeth over 10 years.19 For more detailed information regarding prognosis, see Chapter 18.

Effectiveness of Periodontal Maintenance

The long-term success of periodontal and maintenance therapy has been documented in both prospective and retrospective studies.6 These studies demonstrated that surgical and nonsurgical periodontal therapies were effective in halting the destructive disease if routine professional maintenance was followed. Maintenance care must begin soon after active therapy and must occur at 3- to 4-month intervals. Conversely, periodontal therapy without comprehensive maintenance care resulted in higher rates of loss of attachment than expected without treatment.20 In fact, alveolar bone loss and tooth mortality rates in unmaintained individuals have been reported to be twice those observed in patients receiving maintenance therapy.21 Furthermore, regular effective plaque biofilm control by the patient, in addition to proper maintenance care by the clinician, is necessary to maintain the results of periodontal therapy.17 Poor oral hygiene permits an environment for opportunistic reinfection by pathogenic microbes, possibly resulting in disease progression.

Determinants of Successful Periodontal Maintenance

The success of periodontal treatment relies on surgical and nonsurgical procedures for thorough root debridement and long-term maintenance through periodic professional therapy and daily personal oral hygiene. There are several integrated factors that contribute to the success of periodontal maintenance, as listed in Table 17-2.

TABLE 17-2

Determinants of Successful Periodontal Maintenance

| FACTORS | RATIONALE |

| •Collaboration among periodontist, dentist, and dental hygienist is established. | •This ensures that all oral care providers understand the patient’s goals, the treatment plan, and case prognosis. |

| •Partnership between patient and oral health care team is created. | •This facilitates a positive relationship and favorable outcome. |

| •Patient accepts responsibility for oral health. | •Success relies on the patient’s commitment to achieve and maintain oral health. |

| •Maintenance of periodontal health is influenced by patient’s overall condition. | •Factors to be considered include the nature and severity of periodontal disease, systemic health, mental health, and host response to therapy. |

Objectives of Periodontal Maintenance

The overall objective of periodontal maintenance is to prevent the development of new or recurrent periodontal disease through supervised care and to preserve a functional and comfortable dentition for life. Specifically, there are five underlying objectives22:

• Preservation of clinical attachment levels

• Maintenance of alveolar bone height

Preservation of Clinical Attachment Levels

Monitoring the gain or loss of clinical attachment levels and probing depths is necessary to assess periodontal health. A gain of clinical attachment and improved probe depth measurements are common findings after active periodontal therapy. However, long-term results are highly dependent on patient compliance with maintenance care and the frequency of maintenance visits. For poorly maintained patients with insufficient plaque biofilm control, clinical inflammatory parameters soon resemble those observed before treatment and deeper probe depths, indicating the continued loss of attachment and alveolar bone, are common.17

Reductions in probe depths after periodontal therapy result from healing at the epithelial attachment and reduction of gingival swelling.8 Therefore, increasing probe depths are the most valuable and practical measurements to predict clinical attachment loss during maintenance therapy. They are more predictable than increased plaque biofilm scores, bleeding sites, or amount of suppuration.23

Evaluation of the stability of periodontal health requires thorough documentation of probe depths and clinical attachment levels. These measurements are essential for monitoring patient periodontal status during the maintenance phase. However, there are no national guidelines recommending the frequency of these comprehensive evaluations. Suggestions include evaluation at annual or biannual intervals or at every maintenance visit.24 Despite this lack of standardization of the comprehensive evaluation, every recall appointment must include a periodontal evaluation, regardless of whether it is a comprehensive or a monitoring assessment. The monitoring examination has been described as a “directed” assessment in which all sites are evaluated for inflammatory changes, with problem sites recorded. Thus, comparisons with baseline data can be made and significant changes identified.

Control of Inflammation

Maintenance of satisfactory periodontal health requires control of inflammation and prevention of recurrent disease. Toward this end, personal oral hygiene is one of the most important aspects of periodontal maintenance. Studies of supervised maintenance programs that focused on refinement of personal oral hygiene skills showed that improved gingival and periodontal conditions were achieved in compliant subjects.25 In contrast, Lindhe and colleagues26 showed that maintenance patients with imperfect plaque biofilm control continued to exhibit loss of periodontal attachment. Other studies have shown that patients with imperfect plaque biofilm control could maintain clinical attachment levels as long as regular, professional, subgingival instrumentation was performed.27 Poor oral hygiene alone, resulting in marginal gingival inflammation in maintenance patients, may not lead to increased periodontal destruction. Evidence-based review confirms that routine professional care, including disruption of the subgingival microbial biofilm ecosystem, plays a vital role in conjunction with daily oral home care in maintaining a stable periodontium.

Evaluation and Reinforcement of Personal Oral Hygiene

Daily personal oral hygiene, in conjunction with professional maintenance care, is the foundation of preventive periodontics. Each maintenance visit must include an evaluation of the patient’s oral home care and personalized instruction on proper plaque biofilm control techniques, as indicated by current assessments. It has been shown that in patients who had 2 years of professionally monitored plaque biofilm control emphasizing meticulous oral hygiene, the subgingival microbiota changed to one associated with health.26 Although perfect supragingival plaque biofilm control is an unrealistic goal for most patients, the amount of plaque biofilm can be reduced to levels tolerated by the body. This change can prevent the reestablishment of gingivitis or reinfection by opportunistic periodontal pathogens. Using behavioral modification and motivational techniques, the dental hygienist plays a role in plaque biofilm control education that is equally as important and demanding as the more technical aspects of maintenance therapy.

Compliance with Periodontal Maintenance

The overall success of periodontal therapy depends significantly on patient compliance with recommended recall schedules and personal oral hygiene regimens. Many studies show that patients who comply with maintenance recommendations have better periodontal health and overall prognoses than patients who forgo maintenance care.27 Periodontal patients must be made aware that continued maintenance care and personal plaque biofilm control are essential elements of successful treatment. Failure to comply with these regimens can lead to further periodontal destruction and possibly to tooth loss. In essence, periodontal disease can be arrested and controlled, but not cured. Compliance requirements seem demanding, but for most individuals, the benefits of compliance far outweigh the risks of periodontal disease and tooth loss.

Compliance with Recommended Maintenance Intervals

Numerous studies verify that periodontal health is maintained in individuals who comply with suggested maintenance intervals, regardless of the type of surgical or nonsurgical therapy received.6 In contrast, patients who do not comply or who comply erratically have increased periodontal deterioration. Typically, patients who comply erratically show an increased loss of periodontal attachment,28 require more corrective surgical procedures,29 and tend to lose more teeth.18

Large variations are seen in studies describing patient compliance with recommended maintenance therapy. In private periodontal practices, 16% to 95% of patients complied with 3-month maintenance intervals.29,30 University-based studies reported relatively low percentages of maintenance schedule compliance, ranging from 11% to 45%.31,32 These discrepancies, like compliance, may have many causes and are not easily explained. However, it appears that obtaining patient cooperation is a major challenge for dental hygienists.

The reasons patients do not comply with maintenance schedules are complex, because each individual has different needs and experiences. Some of these reasons are detailed in Box 17-1. In general, noncompliance is seen more commonly in patients who do not perceive chronic diseases to be life-threatening.32 It is the dental hygienist who must take the time to identify the factors that will be personally motivating for each patient and individualize instruction.

Compliance with Recommended Oral Hygiene Regimens

Reported rates of compliance with suggested oral hygiene procedures vary, but they are often disappointing. A survey of patients in a private dental practice showed approximately equal proportions of patients claiming to be highly, moderately, and poorly compliant.33 Other findings suggest that at most, 51% of patients claim high compliance, 38% report moderate compliance, and 11% are noncompliant 30 days after oral hygiene instruction.34 Patient compliance with the use of interproximal cleaning devices appears no better, with less than 50% compliance.35

Periodontal patients report that oral hygiene procedures are cumbersome and time-consuming. Improved plaque biofilm control may be achieved in these patients by introducing an electric toothbrush, which they perceive as faster and simpler than manual brushing.36 Compliance with suggested oral hygiene regimens may also be directly related to the number of cleaning aids recommended at the maintenance visit. When more oral hygiene aids are recommended, decreased compliance is observed.37 The dental hygienist should therefore avoid giving instruction for every possible aid at one time and instead create a plan for implementation of recommended tools over time.

Strategies to Improve Patient Compliance

Strategies to increase compliance start with increasing the patient’s knowledge. The importance of periodontal maintenance, the benefits of preventive therapy, an appreciation of improved oral health, and the dental hygienist’s commitment to maintaining a caring attitude and providing the highest quality professional services should be emphasized. Recommendations to improve compliance are listed in Table 17-3.32

TABLE 17-3

Recommendations to Improve Patient Compliance

| STEP | RATIONALE |

| 1. Simplify | Speaking at the patient’s level of understanding enhances communication efforts; patients tend to remember what is told to them first; the simpler the required behavior, the more likely it is that the patient will comply. |

| 2. Accommodate | Recommendations should be tailored to the patient’s needs and lifestyle; satisfied patients tend to comply more than dissatisfied patients. |

| 3. Remind patients of appointments | Patients must recognize the importance of frequent recall appointments to maintain periodontal health. |

| 4. Keep records of compliance | Noting the patient’s history of compliance with recommended maintenance schedules and plaque control regimens provides legal documentation as well as a guideline for behavior modification. |

| 5. Inform | Written specifications of the recommended regimens can be reminders for patients. |

| 6. Provide positive reinforcement | Positive feedback enhances compliance more than a negative approach. |

| 7. Identify | If noncompliance is suspected in a patient, the consequences of failure to comply should be discussed before therapy is initiated. |

(From Wilson TG. Compliance: a review of the literature with possible applications to periodontics. J Periodontol. 1987;58:709.)

Research suggests that the highest patient dropout rate occurs during the first year of maintenance therapy. Up to 35% of patients who received periodontal therapy thought that treatment was complete after the initial phase, before maintenance even began.38 Therefore, special attention should be given to patients at the initiation of treatment and again at the commencement of periodontal maintenance to emphasize the importance of compliance and establish a positive long-term relationship.

Economic considerations are a common source of concern about suggested maintenance intervals. Socioeconomic status, educational level, and perception of oral health may affect a patient’s attitude toward purchasing oral health care services. The cost of maintenance appointments is often a primary determinant of patient compliance. A survey of noncompliant maintenance patients in a private periodontal practice showed that many were concerned about the long-term expense of treatment.32 This concern may reflect a lack of appreciation for the cost-effectiveness of maintenance care. Because chronic periodontal disease is often asymptomatic, disease progression goes unnoticed. Subsequent re-treatment can be much more expensive than maintenance in terms of financial cost and tooth loss. The dental hygienist can correct these misconceptions and help patients understand the preventive and cost-effective aspects of maintenance care.

The popularity of healthy lifestyles and physical fitness has skyrocketed and health concerns have become a part of mainstream American life. The promotion of physical and mental health and well-being focuses on prevention. This requires individuals to make decisions leading to healthier lifestyles. The promotion of oral health is a part of this trend. The media, federal and state governments, employers, health professionals, family, and friends greatly influence an individual’s attitude toward health. Because oral health is often a reflection of systemic health, the dental hygienist is in an excellent position to encourage patients to maintain both their oral and physical health. As evidence continues to emerge suggesting a link between periodontal and systemic diseases, patients’ awareness of oral health as an essential component of overall well-being will increase. Moreover, evidence suggests that health-related behavior, including compliance, is often dictated by the individual’s beliefs about health.38 Hence, an appreciation of oral health is likely to improve compliance and ultimately help achieve success in periodontal maintenance.

As a health professional, the dental hygienist is obligated to educate and motivate patients continually to comply with recommendations for good oral health. The establishment of a partnership between the patient and the dental hygienist is essential to facilitate this learning relationship. Dental hygienists have sometimes been perceived as indifferent to patient concerns.32 Maintaining a caring attitude and good rapport encourages patients to ask questions and express their fears and concerns regarding therapy. Dental hygienists should take advantage of opportunities to teach and provide a better understanding of maintenance therapy; this understanding, in turn, promotes patient compliance.

The Maintenance Appointment

• To evaluate the stability of results after active therapy

• To remove bacterial plaque biofilm accumulations on the tooth surface thoroughly

• To eliminate all factors that favor the persistence of pathogenic bacteria

To achieve these objectives, the maintenance visit consists of a medical history update, a complete periodontal and dental examination, a radiographic examination if needed, a review of personal oral hygiene, and removal of supragingival and subgingival plaque biofilm and calculus. The maintenance visit is outlined in Box 17-2. On average, the maintenance appointment lasts 1 hour and generally provides sufficient time for thorough and proper care.39 However, the length of the appointment can be adjusted depending on the needs of the patient. The next section describes the components of a periodontal maintenance appointment, commonly referred to as a maintenance visit or periodontal recall.

Components of the Maintenance Visit

Medical and Dental History Update

Periodontal Evaluation

Probing Pocket Depths

Research shows that changes in clinical attachment are more accurately represented in measurements of attachment loss than by probing depths.40 Determination of attachment loss is made from a fixed reference point on the tooth surface, such as the cementoenamel junction or the margin of a restoration to the base of the pocket. For a complete discussion of measuring attachment loss, see Chapter 8. This procedure is time-consuming but important to include in practice.

Gingival Recession

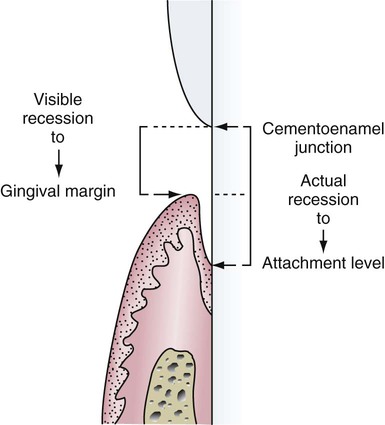

Gingival recession is apparent when the root surface is clinically exposed as a result of apical migration of the junctional epithelium and loss of marginal gingiva, as illustrated in Figure 17-2. It represents increased attachment loss, but it is not equivalent to the measurement of loss of attachment. Recession is measured from the cementoenamel junction to the gingival margin, and when added to probing depths in the area, it provides an estimate of total clinical attachment loss. The exposed root surfaces in the areas of recession are of special concern because of the increased risk for dentin sensitivity or hypersensitivity and carious lesions. The dental hygienist must carefully assess all areas of recession for these conditions.

The left side shows the visible recession measured from the cementoenamel junction to the gingival margin. The right side shows the actual recession measured from the cementoenamel junction to the base of the sulcus. (Modified from Wilkins EM. The gingiva. In: Wilkins EM, ed. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 11th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses