CHAPTER 16 COMPLEX IMPLANT RESTORATIVE THERAPY

Patient Assessment

Patient Assessment

Evaluation of the patient involves much more than just a simple examination of the oral condition. Patients requiring complex care present with myriad physical and psychosomatic issues. Ignoring these issues can doom treatment to failure before it even commences.1–6

The initial patient interview may be the most critical portion of the evaluation process. This step allows the practitioner to ascertain not only the patient’s history but also the patient’s personal goals and objectives. We need to know, in the patient’s own words, the chief complaint and the past and present medical history. With a clear understanding of the patient’s concerns, we can tailor the course of treatment to allow the patient to participate in this complex process in a comfortable, nonthreatening fashion.1–8

The patient’s questions should allow the interviewer to determine why the patient has reached his or her current state. What has kept the patient from care in the past, and what are the patient’s fears of dental treatment? The chief complaint is the starting point for all later presentation for the patient. This allows the team insight into the patient’s mindset. What are the patient’s specific concerns? What treatment has been presented to the patient in the past? Why was the treatment either unsuccessful or never initiated? What we learn from the patient’s history will keep us from repeating failures from the past.1–10

Assessment of the patient’s goals and expectations allows the practitioner to create a treatment plan and presentation that will encourage the patient to accept treatment and achieve a successful result. Although we are first and foremost health care providers, we must also possess the skills and abilities to create a scenario that allows patients to consent to the initiation of treatment. Determination of the patient’s motivational keys is an additional goal of the interview. Because of the intricacy of the treatment, the complexity of the sequence of care, and the generally high fees involved, a treatment presentation directed toward these motivators, or “hot buttons,” may allow the patient to understand the value of the treatment. When we are personally seeking information and have to commit to a decision, we always want to know the benefits to ourselves. Business sales literature lists some of these hot button triggers relative to personal decision making as aesthetics, health, pain, business advancement, self-confidence, embarrassment, sex, and money. When the time comes to present the proposed treatment plan to a patient, knowledge of these motivators is invaluable.11–14 We commit to a course of action based on value—“what’s in it for me”—but we all view value differently. Throughout the evaluation process the dental staff must also assist in determining the patient’s motivators and what the patient is seeking from care, later discussing this information with the dentist. Care must be taken to ensure that a patient does not simply acquiesce to treatment but truly agrees with and comprehends the therapy and its relationship to his or her overall health and well-being.

As discussed in prior chapters, a complete medical history and medication list must be obtained. Patients requiring complex restorative care may be more medically compromised than the average dental patient. The interrelationship between medications, healing, and patient response should never be taken lightly. When necessary, a request for additional information and consultation with the patient’s physician should be obtained before proceeding with care.2–10,15,16,18,19

Dental Evaluation

Dental Evaluation

A traditional dental evaluation is only the starting point when analyzing these severely compromised patients.1–7, 9, 10, 15–18 This should include a written evaluation of the following:

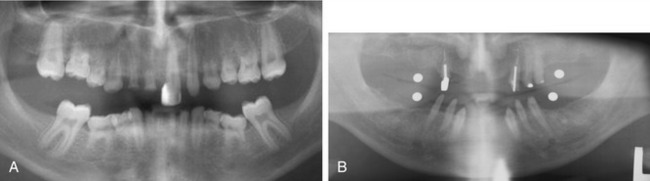

Figure 16-4. A, The panoramic radiograph is the base standard for implant diagnosis and treatment planning. This panoramic radiograph shows the partial anodontia seen in the patient discussed in Case 4. B, Utilization of a 5-mm stainless steel ball bearing is an acceptable method of calibrating a panoramic radiograph when a computed tomographic scan is unavailable or deemed unnecessary. This panoramic radiograph was used in the diagnosis for the patient discussed in Case 1.

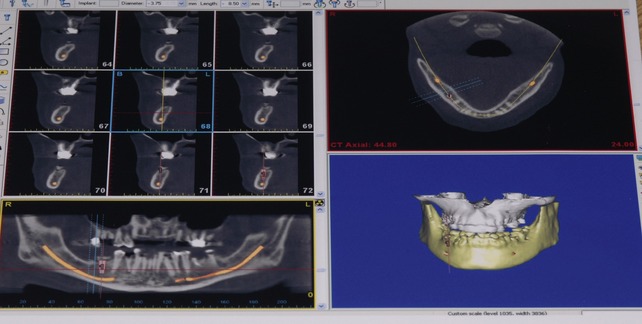

Manipulation of the implant placement around osseous abnormalities, voids, and critical structures within the osseous frame frequently require much more information than can be garnered from a two-dimensional panoramic radiograph. Information from computer-assisted studies provides the surgical and prosthetic team with the precise location and volume of available bone, and the quality of the bone (Figure 16-5). The use of newer software programs provides the ability to generate surgical guides, prosthetic templates, and a provisional or final prosthesis before the beginning of any surgical treatment. Guided surgical and prosthetic therapy will significantly advance the treatment of these complex cases by providing access to areas of bone that were simply too difficult or too dangerous to approach with unguided techniques. These advances in diagnostic planning and directed surgical techniques will allow practitioners to provide implant restorative options to patients previously deemed unrestorable without elaborate surgical manipulations.*

Case Planning

Case Planning

Only after all of these questions and issues are discussed is the team ready to present the treatment plan to the patient.1–5, 10, 15–18, 35–46

Restorative Options

Fixed prosthetic options for the partially edentulous patient are generally variations of traditional crown and bridge techniques. With regard to implants, every attempt should be made not to attach implants to natural dentition.2–6,10,18,47 Creation of a prosthetic result that allows the patient to easily perform personal daily oral hygiene processes also must be discussed carefully with the often-forgotten members of the treatment team, the dental technician and laboratory.48 If large spans of missing teeth cannot be restored safely with a fully fixed prosthesis, a segmental removable prosthesis can be used in combination with fixed crowns and bridges. This type of prosthesis allows replacement of wide edentulous spans without overstressing the implants or natural abutments.* The segmental prosthesis makes use of the same principles as the fully edentulous variation, with the level of retentive stability dependent on the bar attachment devices selected.

Removable prosthetic options come in two basic types: with or without a bar. Lack of a bar definitely reduces the complexity of prosthetic fabrication, but a bar significantly increases the stability of the final prosthesis. The level of stability can range from limited retention of a two-implant self-standing prosthesis to a multi-implant spark erosion bar prosthesis that has the feel of a fixed prosthesis.* It is important for the team to remember, when planning the final restoration, that when patients think of implants they think of stability.

Fixed prosthetic options for the edentulous patient have undergone significant modification in recent years. Aside from fixed crowns and bridgework, the original Brånemark-style hybrid prosthesis is still the model on which most are based.5,53 The use of angled implants and fixation in nontraditional locations such as the zygoma has added tremendous additional treatment options for the patient. In concert with or without guided surgical techniques, these concepts are evolving rapidly.54–5781 The patient’s ability to create a long-term healthy environment must also be part of the planning process when developing the fixed implant prosthesis for the patient. If there is any question as to the patient’s willingness or ability to perform the necessary daily hygiene procedures, a removable prosthesis should be planned.

Treatment Presentation

Treatment Presentation

In general, it is not effective to discuss the specific details of treatment when presenting the plan to the patient. The patient does not need to be taught how to place an implant or achieve proper contouring of a crown during the consultation. Patients often are confused when we try to turn them into doctors by explaining all the intricacies of treatment. We must be sure that our patients understand what is being planned for them, the steps of therapy, and the anticipated outcome as well as the potential risks to achieve our responsibilities of informed consent. However, we must be careful not to overwhelm patients with too much information and create confusion. It should be noted that there are two exceptions to the rule of not discussing the details of the prosthesis with patients: the engineer and the researcher. Because of these individuals’ backgrounds and their more analytical approach to decision making, the practitioner must be ready to provide to them both the value-building piece and the specifics of the therapy during the consultation. It should still be noted that even with such detail-oriented individuals, the decision to commit to treatment is still based on their individual values and goals.4,5, 12–14, 58–62

When the total restorative and surgical treatment plan is finalized, an anticipated timeline must also be presented to the patient. Patients have no basis for comprehending the exceptional complexity of these therapies and the amount of time it takes for healing and fabrication of the final prosthesis. It can easily take from 6 to 24 months to complete a complex treatment plan. It is imperative that during the treatment presentation we address one of the patient’s greatest unspoken concerns over this type of extended therapy: How will they function, both physically and aesthetically, during the course of treatment? 1–5,7,10

Provisionalization

Provisionalization

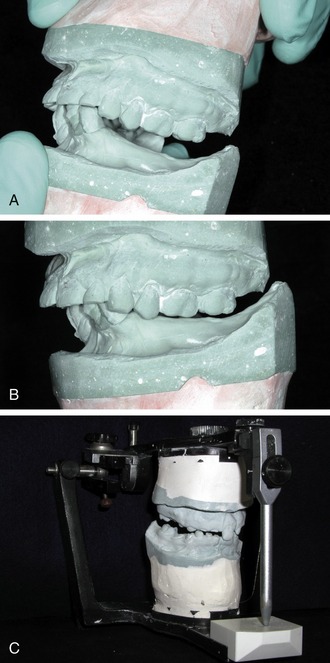

It is always preferable to provide an immediate fixed provisional restoration for the patient. This is generally the most comfortable option for a patient because it obviates the need for a removable prosthesis, which may be foreign to the patient. It also allows for passive healing of the tissues without direct pressure during function, eliminates the risk of movement or dislodgment for the patient, and prevents coverage of the palate when the maxilla is involved (Figure 16-6). As part of the treatment planning process the team must determine before the consultation if it will be possible to place the implant fixtures at the initial surgery.*

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to provide a fixed provisional restoration for every patient. Placement and loading of the implant fixtures are totally dependent on adequate osseous support, acceptable levels of initial torque on the fixtures, and the presence of stable soft tissues at the point of surgery. If implant fixture placement or loading is not initially possible, a complete or partial provisional denture prosthesis may be necessary. This type of prosthesis may be problematic because it is generally in direct contact with the surgerized tissues. Excessive pressure must not be applied over the suture line, underlying grafted bone, subgingival fixtures, or exposed fixtures. To avoid this pressure, a semi-flexible base material should be used on the tissue surface of the prosthesis (Figure 16-7). A variety of materials are marketed as soft or transitional reline materials, and one should be selected based on ease of application and ability to trim cleanly with a bur, blade, or electric hot knife. The material should adapt fully to the current ridge to provide support to the tissues. Because the semi-flexible base has very little strength, consideration must be given to provide enough bulk of acrylic within the prosthesis to prevent fracture during function. Do not assume that the soft liner will provide enough protection to keep an implant with an exposed healing cap totally out of function. All soft lining materials will load an exposed healing cap if in direct contact and this can be problematic during the 2- to 8-week relaxation stage of integration. To prevent this problem, trim away any base material that comes into direct contact with the fixture or healing cap.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses