Chapter 15

Professional, ethical and legal issues

Richard Griffith

INTRODUCTION

Law and ethics are now fundamental to the practice of dentistry and underpin your relationship with the profession and with your patients. Probity lies at the heart of your professionalism and requires strict adherence to a code of ethics and the law.

The law informs dentistry at every stage and it is essential that dental professionals understand and are able to critically reflect on the legal issues relevant to practice. This is particularly true in emergency situations when an appropriate and timely response is required.

When dental professionals treat patients they undertake a duty of care towards those persons not to harm them in accordance with the law of negligence. Where dental professionals provide treatment to a patient for a fee then that treatment will be regulated under the laws of contract with the patient able to sue if the contract is not fulfilled. Dental professionals’ right to touch a patient will be based on the law of consent and the informed and freely given permission of the patient will be a prerequisite to any lawful treatment. The legal principles of confidentiality and negligence regulate the relationship between the dental professional and the patient while they are in the professional’s care.

The standards of the profession and its regulatory body, the General Dental Council, are derived from fundamental human rights principles. These principles largely underpin the law relating to health care and the standards of conduct and performance required of dental professionals by the General Dental Council’s Standards for Dental Professionals (2005a).

THE SCOPE OF A DENTAL PROFESSIONAL’S ACCOUNTABILITY

A registered dental professional is legally and professionally accountable for his or her actions, irrespective of whether they are following the instruction of another or using their own initiative. Healthcare litigation is increasing and patients are increasingly prepared to assert their legal rights. It is perhaps little wonder therefore that the General Dental Council insists that dental professionals are able to practise in accordance with an ethical and legal framework which ensures the primacy of patient and client interest (General Dental Council, 2005a, 2005b).

A thorough and critical appreciation of the legal and professional issues affecting dental practice is essential if you are to develop the professional awareness necessary to satisfy the probity required by the General Dental Council that you are competent to practise as a registered dental professional (see Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Advantages of legal awareness for the dental professional

|

The legally aware dental professional:

|

Defining accountability

In their seminal work on the subject, Lewis and Batey (1982) defined accountability as ‘the fulfilment of a formal obligation to disclose to reverent others the purposes, principles, procedures, relationships, results, income and expenditures for which one has authority’.

An analysis of Lewis and Batey’s definition reveals the fundamental nature of accountability. The ‘fulfilment of a formal obligation’ suggests that accountability has its basis in law. That is, there is a formal or legal relationship between the practitioner and higher authorities (the ‘reverent others’) that are entitled to hold the dental professional to account. The extent of the scrutiny is illustrated by the inclusion of ‘the purposes, principles, procedures, relationships, results, income and expenditures for which one has authority’ in the definition. Put more concisely, to be accountable is to be answerable for the acts and omissions within your practice.

This is the approach adopted by the General Dental Council (2005a), the profession’s regulatory body, who states in Standards for Dental Professionals that:

‘You have a professional responsibility to be prepared to justify your actions, and we may ask you to do so. You must be willing and able to show that you are aware of this booklet; and you have followed the principles it explains.

‘If you cannot give a satisfactory account of your behaviour or practice in line with the principles explained in this booklet, your registration will be at risk.’

Accountability may be defined as being answerable for personal acts or omissions to a higher authority with whom the dental professional has a legal relationship.

Exercising accountability

A common misconception about accountability is that a dentist has some choice over what they are accountable for. Meeting their professional responsibility is often expressed as exercising accountability.

While it is true to say that the General Dental Council sets out the standard of conduct required of dental professionals, accountability cannot be exercised as this would require the practitioner to have control over what they were accountable for. It suggests that dentists can pick and choose whether they wish to be accountable for this action or that patient. This cannot be the case as the purpose of accountability is to protect the public and offer redress to those who have been harmed by dental professionals’ acts or omissions. Dental professionals are answerable through the law to a number of higher authorities and it is these higher authorities, not the professionals themselves, who decide if they are to be held to account.

Accountability has four functions as set out in Table 15.2.

Table 15.2 Functions of accountability

|

Protective function – The purpose of accountability is to protect the public from the acts or omissions of dental professionals that might cause harm. Deterrent function – The threat of sanction available to the higher authorities against registered practitioners is seen as protecting the public by deterring acts or omissions that might cause harm. Regulatory function – By making the dental professional accountable to a range of higher authorities, the law regulates their behaviour and allows action to be taken to protect the public should they breach the regulatory framework. Educative function – Accountability has an educative function in that those found liable have their cases heard in public with a view to reassuring society that only the highest standards of practice will be tolerated. Other practitioners will learn from such cases and refrain from acting in a similar manner. |

Accountable to whom?

Dental professionals owe a formal obligation to answer for their practice to a range of higher authorities. These have a legal relationship with you that enable them to demand that you justify your practice. If you fail to satisfy those requirements, sanctions may be applied against you.

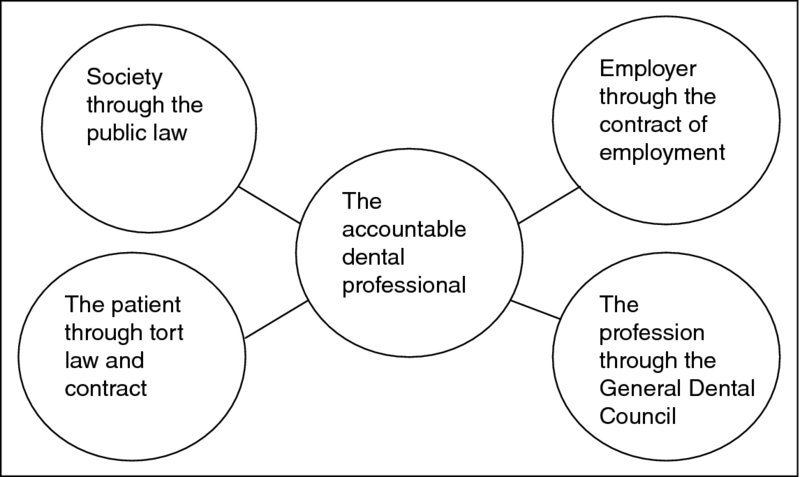

In order to provide maximum protection to the public four areas of law are drawn together and can individually or collectively hold you to account. Figure 15.1 depicts to whom you are accountable as a dental professional and the legal basis of that relationship.

Figure 15.1 Accountability to whom.

Accountability to society

Dental professionals are subject to the same laws as any other member of society. There is nothing about the status of a dentist that exempts them from these laws. If a dentist is suspected of committing a crime during the course of their practice or otherwise they can be called to account.

Accountability to society is achieved through the public law. Many of these laws are derived from Acts of Parliament such as the Road Traffic Act 1988, the Theft Act 1968 or the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. Such Acts are known as public general acts and it is entirely possible to breach them in the course of your practice. A dentist who defrauded the National Health Service (NHS) of £1.4 million, by submitting claims for treating over a hundred patients who were dead and making duplicate claims for others, was jailed for 7 years (Oldham, 2012).

The treatment a dental professional provides to their patient often requires interventions that are personal and intimate in nature. The public law demands that such interventions are only carried out when it is convincingly shown to be medically necessary and by staff who are properly qualified (R v Tabassum, 2000). Where this occurs the dentist’s actions stand outside the criminal law (Airedale NHS Trust v Bland, 1993). However, the acts of the dental professional will lose their immunity if the necessity cannot be made out or the treatment proceeds without either the consent of a capable patient or the best interests of an incapable patient. For example, a dental practitioner who repeatedly touched a female patient in unnecessary intimate examinations was sentenced to 9 months imprisonment for indecent assault that the judge described as a gross breach of trust (Yorkshire Evening Post, 2008).

The public law seeks to protect patients through the regulation of practice and the environment of care. The National Health Service Litigation Authority (2007) estimates that some £500 million is paid annually by the health service in compensation claims and fines for breaching health and safety laws. The cost in human terms can also be high. Mistakes and errors can compromise safety to the point where lives are put at risk and, sadly, fatalities do occur.

To prevent the avoidable loss of life and minimise the days lost to absence, an employer has a legal duty to comply with the requirements relating to health and safety at work. The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 is the basis of health and safety law in the United Kingdom and it sets out general duties which:

- employers have towards employees and members of the public using their service; and

- employees have to themselves and to each other.

Breaching or failing to comply with these duties are criminal offences.

The employer’s general duty is set out in Section 2 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and states that an employer has a duty to ensure so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of employees and any others who may be affected by the undertaking.

The legal standard imposed by the 1974 Act is reasonably practicable or so far as is reasonably practicable. The standard implies a weighing up of the risk against the cost in terms of time, money or trouble of preventing or controlling the risk.

The duty of employees at work is set out in Section 7 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 that states that:

‘It shall be the duty of every employee whilst at work:

- To take reasonable care of their own health and safety and of any other person who may be affected by their acts or omissions; and

- To co-operate with their employer so far as is necessary to enable that employer to meet their requirements with regard to any statutory provisions’.

As well as a duty under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 a dental professional is also under a professional duty to act to identify and minimise the risk to patients and clients (General Dental Council, 2005a).

The General Dental Council (2005a) has acknowledged that medical emergencies can occur at any time so all members of staff must know their role in the event of a medical emergency. It is essential therefore that dental professionals and their staff are suitably trained in dealing with emergencies and practise together regularly in simulated emergency situations to maintain their competence. This includes where to locate and use an automated external defibrillator.

A dental professional who raises an issue of health and safety with an employer either directly or through a union is entitled to protection from dismissal and victimisation under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998. Under the Act each NHS employer has a duty to establish a procedure for employees to raise concerns where:

- a criminal offence has been, is being or is likely to be committed; or

- the health or safety of an individual has been, is being or is likely to be endangered.

It is essential that employers and staff work together to ensure effective implementation of health and safety measures. This joint approach helps to promote and raise awareness among employers and staff, thereby creating a positive safety culture.

Workplace risk assessments

A risk assessment is the identification of hazards present in the workplace and an estimate of the risk associated with performing the task. A hazard is something that has the potential to cause harm and a risk is the likelihood of that hazard causing an accident or an incident.

There is a legal duty to perform risk assessments under the provisions of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999.

Once a hazard has been identified the likelihood of the risk occurring and the severity of the harm must be considered. The law requires that risks should be reduced so far as is reasonably practicable. That means that the degree of risk should be balanced against the time, trouble, cost and physical difficulty of taking measures to avoid it.

On identifying a risk, steps must be taken to minimise it by:

- Elimination of the hazard at source, if this is not possible then the hazard must be reduced;

- If the hazard has to be reduced then action must be taken to control the risk by introducing workplace precautions such as alarms, training and information, safety cabinets, ventilation systems, etc.;

- Once workplace precautions have been introduced then a system to monitor compliance with those precautions must be put in place.

Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007

Under the provisions of this Act dental practices, companies and organisations can be found guilty of corporate manslaughter as a result of serious management failures resulting in a gross breach of a duty of care.

The Act, which came into force on 6 April 2008, clarifies the criminal liabilities of companies including large organisations where serious failures in the management of health and safety result in a fatality.

Dental practitioners can also face gross negligence manslaughter charges where a patient dies as a result of a breach of duty.

A dentist was initially investigated for manslaughter following the death of a child after a general anaesthetic was administered for the extraction of a tooth. The charges were later reduced to five offences under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 to which the dentist pleaded guilty. The offences included:

- failure to notify a local hospital that a general anaesthetic was taking place;

- failure to provide the appropriate oxygen monitor;

- failure to provide an assistant for the anaesthetist;

- failure to provide adrenaline in the surgery; and

- failure to estimate the weight of the patient before the operation.

Source: Evans (2001)

Medicines

Modern dental practice often requires the use of medicines in the treatment of patients. While medicines are used for their therapeutic benefits they can and do cause adverse effects in some patients. In Forman v Saroya (1992) a woman contracted hepatitis as a result of a reaction to halothane anaesthetic administered by her dentist. The dentist ought to have known of her susceptibility because she had suffered a similar reaction when he had given it on a previous occasion. The patient experienced severe abdominal pains soon after the halothane anaesthetic was administered and began to vomit, then suffered lethargy and loss of appetite. These symptoms persisted for just over 2 weeks and required a period in hospital. The dentist was found negligent.

The principal statutory framework for the regulation of medicines are the Human Medicines Regulations (2012). They regulate the licensing, supply and administration of medicines. The Secretary of State for Health has a duty under 2012 regulations to place on prescription only medicines that represent a danger to the patient if their use is not supervised by an appropriate practitioner. Therefore, prescription-only medicines may only be administered by or in accordance with the directions of an appropriate practitioner (Human Medicines Regulations, 2012, reg. 214).

Appropriate practitioners include registered dentists who have their own formulary of medicines from which they are authorised to prescribe (Human Medicines Regulations, 2012, reg. 214). Other dental professionals are not appropriate practitioners and generally must only administer medicines in accordance with the directions issued by an appropriate practitioner.

A degree of flexibility over the supply and administration of prescription-only medicines to patients has been provided by the introduction of Patient Group Directions which is a written instruction for the supply or administration of a licensed medicine in an identified clinical situation where the patient may not be individually identified before presenting for treatment.

A Patient Group Direction is drawn up locally by doctors, pharmacists and other health professionals and must meet the legal criteria set out in the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, schedule 16. Patient Group Directions can only be used by registered healthcare professionals acting as named individuals, and a list of individuals named as competent to supply and administer medicines under the direction must be included.

The Human Medicines Regulations 2012, reg. 230 and 232 exempt registered health professionals from the need to obtain a prescription to supply a prescription-only medicine if they act according to a valid Patient Group Direction when assisting a dentist or working in a dental practice in England and Wales.

A Patient Specific Direction is a written instruction for prescription-only medicines to be supplied for administering to a named patient without a prescription. An example would be an instruction by a dentist to supply and administer a medicine in the surgery such as an antibiotic.

To be valid the Patient Specific Direction must:

- be in writing;

- relate to the particular person to whom the medicine is to be administered; and

- be issued by a dentist.

Exemption in an emergency

In an emergency certain prescription-only medicines may be supplied and administered without prescription. The Human Medicines Regulations 2012, reg. 238 allows for the parenteral administration of prescription-only medicines including adrenaline and hydrocortisone injection for the purpose of saving life in an emergency and there is no specific restriction on who is entitled to administer these medicines.

Accountability to the patient

As well as being accountable to society in general, dental professionals are also accountable to the individual patients in their care. The tort or civil law system allows a patient to sue for compensation if they believe that harm has been caused through carelessness. Liability for carelessness is given its legal expression in the law relating to negligence.

Negligence is a civil wrong and best defined as actionable harm. That is, a person sues for compensation because they have been harmed by the carelessness of another person.

Negligence in the healthcare setting has developed under the common law by judges setting rules through decided cases. In certain circumstances, called duty situations, the nature of the relationship between people gives rise to a duty of care. For example, a manufacturer owes a duty to the consumer of his product (Donoghue v Stevenson, 1932) and one road user owes a duty of care to the other road users in his vicinity (Rouse v Squires, 1973). Similarly the dentist–patient relationship gives rise to a duty of care (Kent v Griffiths, 2001). Dentists owe their patients a duty of care and are accountable to the patient if they cause harm by breaching that duty.

In civil law dental professionals are expected to meet the standard of care set by reference to Bolam v Friern HMC (1957). Known as the Bolam test, it requires that dental professionals meet the standard of the ordinary skilled person exercising and professing to have that special skill or art (Gold v Haringey HA 1998).

Case law demonstrates that the standard covers the whole of the professional relationship with the patient and includes direct care (Bayliss v Blagg and another, (1954)), advice giving and record keeping (Greenfield v Irwin (A Firm), 2001), even the standard of handwriting (Prendergast v Sam and Dee, 1989). If the dental professional’s actions were in keeping with a respected body of professional opinion then practice will not have fallen below the standard required in law and there will be no liability in negligence (Bolam v Friern HMC, 1957). This will be the case even if there were different ways of performing a task. A judge cannot find negligence just because he prefers one professional’s view over another (Maynard v West Midlands RHA, 1984).

However, in Bolitho v City and Hackney HA (1997) the House of Lords held that any expert evidence used to support a dentist’s actions must stand up to logical analysis. That is, the existence of a common practice does not necessarily mean that it is not negligent. A defendant will not be exonerated because others too are negligent or because common professional practice is slack.

The duty of care to the patient also requires dental professionals to keep their knowledge up to date throughout their career (Roe v Ministry of Health, 1954).

Emergencies

Dental professionals continue to owe their patient a duty of care in an emergency situation. They are expected to be able to respond effectively to the common emergencies that might arise in dental surgeries. They are expected to ensure that their practice is up to date and evidence based (Reynolds v North Tyneside Health Authority, 2002).

In relation to treatment decisions taken in an emergency, a dental professional will not be found negligent simply because the reasonably competent dentist would have made a different decision, given more time and information.

In Wilson v Swanson (1956), the Supreme Court of Canada held that there was no negligence when a surgeon had to make an immediate decision whether to operate during an emergency, when the operation was subsequently found to have been unnecessary.

Moreover, the skill required in the execution of treatment may be somewhat lower because an emergency may overburden the available resources, and, if a dental professional is forced by circumstances to do too many things at once, the fact that he or she does one of them incorrectly would not lightly be taken as negligence.

Carelessness as a crime

Although legal proceedings for carelessness are usually instigated at civil law, it is possible to face criminal prosecution where gross negligence has occurred. In R v Misra and Srivasta (2004) the Court of Appeal stated that a health p/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses