Metabolic and Genetic Diseases

Metabolic Conditions

Paget’s Disease

Paget’s disease, or osteitis deformans, is a chronic, slowly progressive metabolic disorder of bone of undetermined cause (Box 15-1). Etiologic theories include infection by paramyxovirus and mutations in several genes that are involved in osteoclastogenesis. Altered osteoclast development and function result in abnormal bone remodeling. Osteoblast function may also be abnormal in Paget’s disease. This condition generally progresses through several stages that include an initial resorptive phase, followed by a vascular phase, and eventually by a sclerosing phase.

Clinical Features

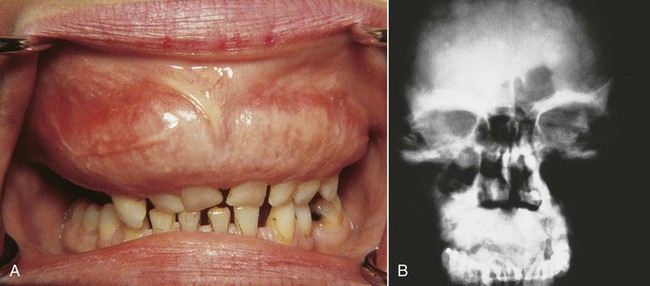

The most common sites of involvement include the pelvis, skull, tibia, vertebrae, humerus, and sternum. The jaws are affected in approximately 20% of patients, and the maxilla is involved twice as often as the mandible (Figure 15-1). At initial presentation, symptoms often relate to deformity or pain in the affected bone(s). Bone pain is described as deep and aching. A perception of elevated skin temperature over the affected bone is often noted because of the hypervascularity of the underlying bone. Neurologic complaints—including headache, auditory or visual disturbances, facial paralysis, vertigo, and weakness—may be related, in large part, to narrowing of the skull foramina, resulting in compression of vascular and neural elements. Approximately 10% to 20% of patients are asymptomatic and are incidentally diagnosed after radiographic or laboratory studies are performed for unrelated problems.

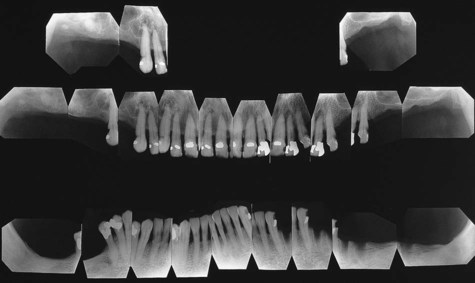

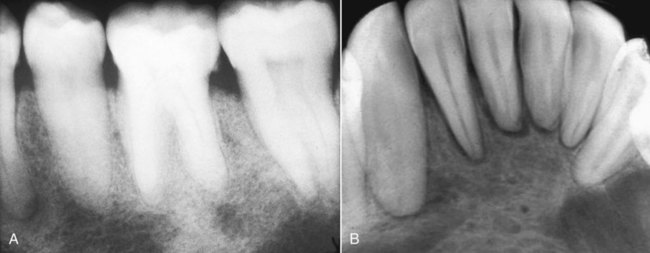

Classic radiographic findings in the late stage of Paget’s disease are due to bony sclerosis providing a patchy radiopaque pattern described as resembling cotton or wool. In the jaws, this pattern of bone change may be associated with hypercementosis or resorption of tooth roots, loss of lamina dura, and obliteration of the periodontal ligament space (Figures 15-2 and 15-3).

Histopathology

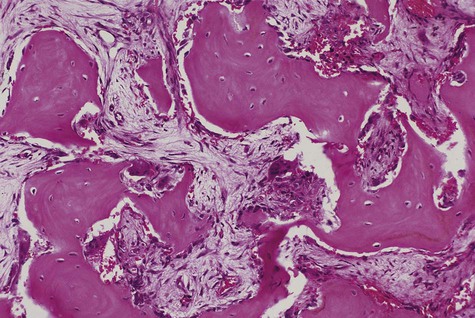

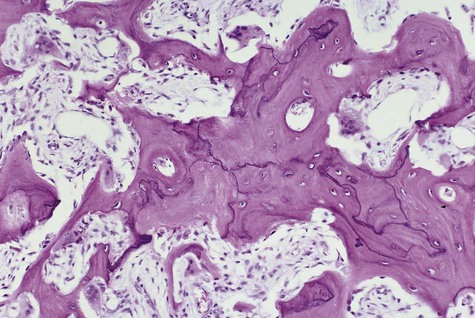

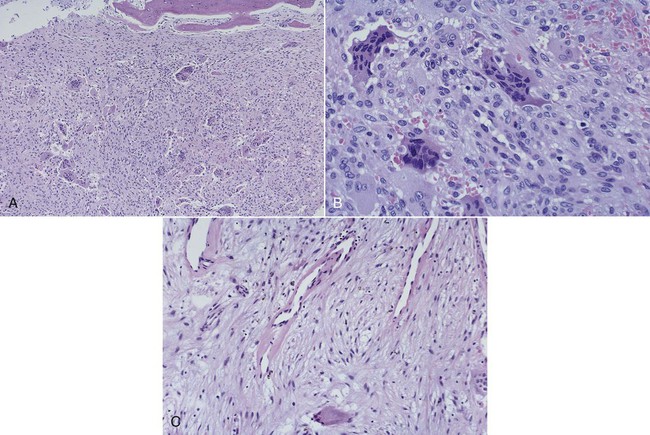

In the initial resorptive phase, random overactive osteoclastic bone resorption is evident. Resorbed bone is replaced by vascularized connective tissue in company with prominent osteolysis and osteogenesis. Bone eventually develops a dense mosaic pattern as a result of reversal lines in increasingly sclerotic bone, as osteoclasts give way to osteoblasts (Figures 15-4 and 15-5).

Treatment

The primary indicator for therapeutic intervention is patient discomfort. Elevation of alkaline phosphatase levels to twice normal levels is also an indication for treatment. Therapy has been directed at controlling osteoclast formation and function. The use of calcitonin and bisphosphonate has been effective. Both suppress bone resorption and deposition, as reflected in a reduction in the biochemical indices, including alkaline phosphatase and urinary hydroxyproline levels. A 50% reduction in either index constitutes a good therapeutic response (see Chapter 13 for complications of bisphosphonate therapy).

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism may be one of three types: primary, secondary, or hereditary (Box 15-2). Rarely, hyperparathyroidism may be associated with a Noonan-type syndrome, a complex, autosomal-dominant inherited trait comprising short stature, unusual facies, mental retardation, and cardiac defects.

Clinical Features

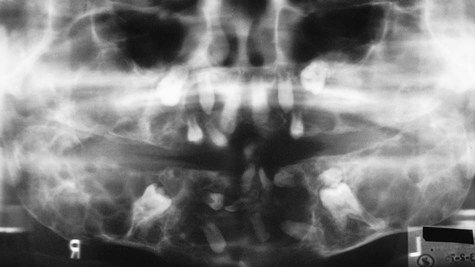

Severe osseous changes (called, in the past, osteitis fibrosa cystica) are the result of significant bone demineralization, with fibrous replacement producing radiographic changes that appear cystlike. In the jaws, these lesions microscopically resemble central giant cell granuloma. Less obvious radiographic changes may include an osteoporotic appearance of the mandible and maxilla, reflecting more generalized resorption (Figure 15-6). Loosening of the teeth may occur, as well as corresponding obfuscation of trabecular detail and overall cortical thinning. Partial loss of the lamina dura is seen in a minority of patients with hyperparathyroidism (Figures 15-7 and 15-8). Pulpal obliteration, with complete calcification of the pulp chamber and canals, has been reported in association with secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Hyperthyroidism

Although the oral manifestations of this condition are not specific, they are consistent (Box 15-3). In children, premature or accelerated exfoliation of deciduous teeth and the concomitant rapid eruption of permanent teeth are often noted. In adults, osteoporosis of the mandible and maxilla may be found. On occasion, patients may complain of a burning tongue, as well as other, nonspecific symptoms. Of interest is a reported threefold increase in the incidence of dental erosion in these patients in comparison with euthyroid control subjects.

Hypothyroidism

The key clinical features are listed in Box 15-4. Diagnosis is based on the history, the physical examination, and determination of serum levels of TSH, and tetraiodothyronine (T4). In typical hypothyroid patients with primary disease, T4 levels are low (sometimes normal) and TSH levels are high (compensatory pituitary reaction). In secondary disease in which the pituitary gland is malfunctioning, both T4 and TSH levels are low. Treatment is based on gradual replacement with synthetic and natural thyroid hormone preparations.

Hypophosphatasia

Four clinical types of hypophosphatasia have been recognized:

1. A congenital type has a 75% rate of neonatal mortality.

2. An early infantile type appears within the first 6 months of life, with a mortality rate of 50%. Renal calcinosis, as well as risks of cranial synostosis, delayed motor development, and premature loss of teeth, may accompany this disease.

3. A late infantile or childhood type begins between 6 and 24 months of age. Skeletal findings tend to be less pronounced, but abnormalities of long bone structures, including irregular ossifications at the metaphysis, may be observed, along with rickets-type changes at the costochondral junctions. Of importance in this form of the disease is premature loss of the anterior primary teeth, often the first sign of the illness.

4. The adult type, although distinctly uncommon, is characterized by bone pain, pathologic fractures, and a childhood history of rickets.

Acromegaly

Clinical Features

Clinical signs and symptoms result from local effects of the expanding pituitary mass and the effects of excess growth hormone secretion (Figure 15-9). Affected individuals present with hyperhidrosis; coarse body hair; muscle weakness; paresthesia, especially carpal tunnel syndrome; dysmenorrhea; and decreased libido or impotence. Sleep apnea, hypertension, and heart disease are also encountered. Skin tag formation is common and may be a marker for colonic polyps. In the facial bones and the jawbones, new periosteal bone formation may be seen, as well as cartilaginous hyperplasia and ossification. Resultant orofacial changes include frontal bossing, nasal bone hypertrophy, and relative mandibular prognathism or prominence. Enlargement of the paranasal sinuses, as well as secondary laryngeal hypertrophy, produces a rather deep, resonant voice, which is typical of acromegaly. Overall coarsening of the facial features is noted, resulting from connective tissue hyperplasia.

Genetic Abnormalities

Cherubism

Clinical Features

Cherubism affects the maxilla and/or mandible and usually is found in children by 5 years of age (Box 15-5). The term cherubism has been used to describe patients with cherubic facies of marked fullness of the jaws and cheeks and upwardly gazing eyes. The mandibular angle, ascending ramus, retromolar region, and posterior maxilla are most often affected. The coronoid process can also be involved, but the condyles are always spared. A vast majority of cases occur only in the mandible. The bony expansion is most often bilateral, although unilateral involvement has been reported. The specific gene maps to chromosome 4p16.3, which encodes the SH3-binding protein, SH3BP2.

Patients typically have painless symmetric enlargement of the posterior region of the mandible, with expansion of the alveolar process and ascending ramus. The clinical appearance may vary from barely discernible posterior swelling of a single jaw to marked anterior and posterior expansion of both jaws, resulting in masticatory, speech, and swallowing difficulties (Figures 15-10 and 15-11). Intraorally, a hard, nontender swelling can be palpated in the affected area.

With maxillary disease, involvement of the orbital floor and the anterior wall of the antrum occurs. Superiorly directed pressure on the orbit results in increasing prominence of the sclera and the appearance of upturned eyes. The palatal vault may be reduced or obliterated. Maxillary involvement usually results in the greatest deformity. All four quadrants of the jaws may be simultaneously involved with this painless process of bony expansion (Figure 15-12). Premature exfoliation of the primary dentition may occur as early as 3 years of age. Displacement of developing tooth follicles results in poor development of selective permanent teeth and ectopic eruption or impaction. Permanent teeth may be missing or malformed, with the mandibular second and third molars most often affected. Significant malocclusions can be anticipated even with unifocal involvement.

Histopathology

Histologically, the lesions are composed of a vascularized fibrous stroma containing multinucleated giant cells, resembling central giant cell granuloma (Figure 15-13). Mature lesions exhibit a large amount of fibrous tissue and fewer giant cells. A distinctive feature that is often present is eosinophilic perivascular cuffing of collagen surrounding small capillaries throughout the lesion.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses