Medical Conditions

• Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

• Oral Anticoagulation Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Congestive Heart Failure

Examination

Maxillofacial. Findings consistent with a mildly displaced Le Fort I fracture (see the section Le Fort I Fracture in Chapter 8).

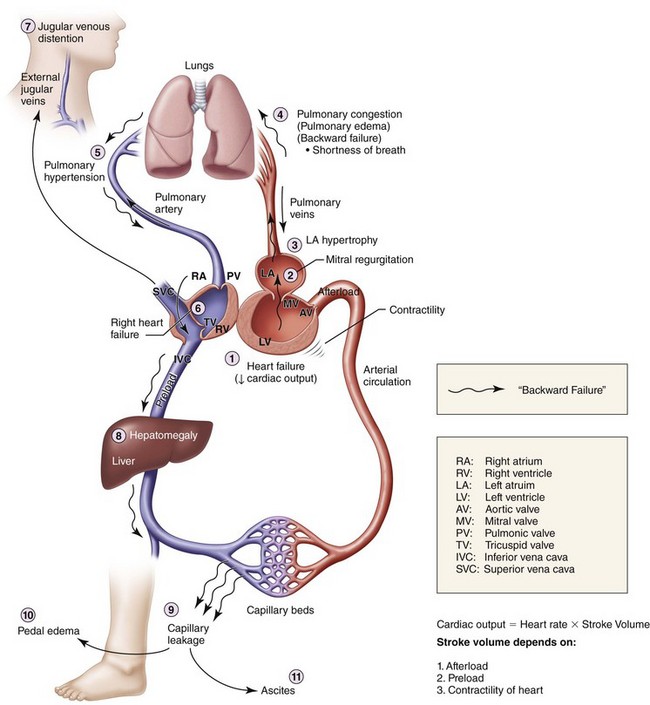

Extremity. Lower extremities show 3+ pitting edema at the ankles (significant fluid in the extravascular compartments due to venous congestion, causing capillary leakage; this is usually first noted in the lower extremities due to the added effect of gravity; Figure 15-1).

Labs

Brain natriuretic peptide level was 2,000 pg/ml (normal is less than 100 pg/ml).

Electrocardiogram Findings

The electrocardiographic findings for the current patient were as follows:

• Rate. Tachycardic at 120 bpm

• Rhythm. Regular; each P wave followed by a QRS complex; each QRS complex preceded by a P wave; QRS complexes occurring at regular intervals

• Axis. Positive deflection in lead I; negative deflection in lead aVF (indicative of left-axis deviation secondary to left ventricular hypertrophy)

• Intervals. PR interval less than 0.20 second, or 5 small boxes on electrocardiograph paper (more than 5 small boxes is consistent with first-degree atrioventricular node block); QRS complex less than 0.12 second, or 3 small boxes (more than 3 small boxes indicates widened QRS complex); QT interval less than half the distance from QRS complex to QRS complex (normal)

• Infarctions. Q waves in leads V1 through V5 (hallmark of old anteroseptal myocardial infarction); no flipped T waves, and no ST-segment elevation or depression (signs of acute ischemic events)

• Other. Loss of precordial R wave progression in leads V1 through V6 (suggestive of old anteroseptal MI and loss of anterior electrical forces)

Discussion

• Class I: Symptoms of heart failure only at levels that would limit normal individuals

• Class II: Symptoms of heart failure with ordinary exertion

• Class III: Symptoms of heart failure on less than ordinary exertion

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association classification and guidelines for the treatment of heart failure can be found in Table 15-1.

Table 15-1

Classification and Guidelines for the Treatment of Heart Failure

| Stage | Characteristics | Treatment |

| A | High risk for heart failure without structural heart disease or symptoms | ACEI or ARB |

| B | Structural heart disease without signs or symptoms | ACEI or ARB + β-blocker (devices such as defibrillators in appropriate patients) |

| C | Structural heart disease with prior/current symptoms of heart failure. | Routine use of diuretics, ACEI, or β-blockers, and aldosterone antagonist, ARB, digitalis, or hydralazine/nitrates, and devices such as biventricular pacing or implantable defibrillator in selected patients |

| D | Advanced heart disease | Medications from stages A through C, with optional use of palliative care, heart transplantation, chronic inotropes, permanent mechanical support, or experimental surgery or drugs |

ACEI, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Data from Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al: ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). American College of Cardiology Web Site. Available at: http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/failure//index.pdf.

Dickstein, K, Cohen-Solal, A, Filippatos, G, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur J Heart Fail. 2008; 10(10):933–989.

Grady, KL, Dracup, K, Kennedy, G, et al. Team management of patients with heart failure: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiovascular Nursing Council of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000; 102:2443.

Hunt, SA, Abraham, WT, Chin, MH, et al. Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53(15):e1–e90.

Knudsen, CW, Omland, T, Clopton, P, et al. Diagnostic value of B-type natriuretic peptide and chest radiographic findings in patients with acute dyspnea. Am J Med. 2004; 116:363.

Young, JB, Gheorghiade, M, Uretsky, BF, et al. Superiority of “triple” drug therapy in heart failure: insights from the PROVED and RADIANCE trials—prospective randomized study of ventricular function and efficacy of digoxin; randomized assessment of digoxin and inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 32(3):686–692.

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Treatment

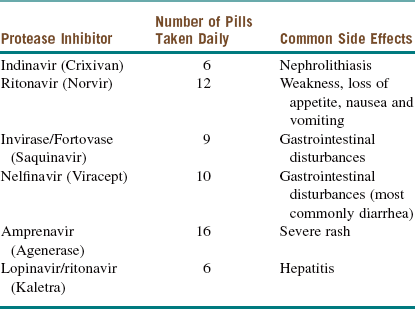

There is some controversy regarding the optimal time to initiate treatment for patients who are seropositive for HIV. Most infectious disease specialists start pharmacotherapy when the CD4 count drops below 50 cells/µl. Regardless of the CD4 count, treatment should be initiated as soon as possible in patients with HIV nephropathy, pregnant patients, and those coinfected with hepatitis B. Current recommendations consist of a combination of a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI; Table 15-2), a non–nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI; Table 15-3), protease inhibitors (Table 15-4), integrase inhibitors, fusion inhibitors, and CCR5 antagonists. A combination of these medications is commonly referred to as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

Table 15-2

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

| Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor | Abbreviation | Side Effects |

| Retrovir | AZT | Anemia, neutropenia |

| Videx | DDI | Pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy (PN) |

| Hivid | DDC | Pancreatitis, PN |

| Zerit | D4T | Pancreatitis, PN |

| Epivir | 3TC | Also used for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection |

| Ziagen | ABC | Rash, death |

Table 15-3

Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

| Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor | Side Effects |

| Nevirapine (Viramune) | Hepatotoxicity, hepatic necrosis during the first 4 weeks |

| Delavirdine (Rescriptor) | Rash, headache |

| Efavirenz (Sustiva) | Teratogenic; Stevens-Johnson rash, hallucinations, nightmares |

Discussion

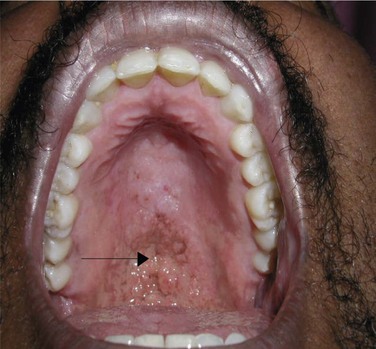

The differential diagnosis of oral lesions seen with HIV may be divided into bacterial, viral, fungal, neoplastic, and idiopathic categories. Bacterial infections may present as acute necrotizing gingivitis or periodontitis. Viral infections, such oral papillomas, are caused by the human papillomavirus and are commonly seen. Fungal infections, such as histoplasmosis or cryptococcosis (Figure 15-2), can cause oral ulcerations. An example of intraoral neoplastic disease is Kaposi sarcoma, caused by human herpes virus 8, which is most commonly seen in homosexual males. Idiopathic xerostomia is commonly seen, resulting in cervical caries.

Aguirre, JM, Echebrria, MA, Ocina, E. Reduction of HIV-associated oral lesion after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999; 88:114–115.

Carey, JW, Dodson, TB. Hospital course of HIV-positive patients with odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Med Oral Radiol Endod. 2001; 91:23–27.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Atlanta: the CDC; 2008.

Depoala, LG. Human immunodeficiency virus disease: natural history and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000; 90:266–270.

Diz Dios, P, Ocampo, A, Miralles, C, et al. Changing prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus–associated oral lesion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000; 90:403–404.

Dodson, TB. HIV status and the risk of post-extraction complications. J Dent Res. 1997; 76:1644–1652.

Dodson, TB. Predictors of postextraction complications in HIV-positive patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997; 84:474–479.

Dodson, TB, Nguyen, T, Kaban, LB. Prevalence of HIV infection oral and maxillofacial surgery patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1993; 76:272–275.

Dodson, TB, Perrott, DH, Gongloff, RK, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus serostatus and the risk of postextraction complications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 23:100–103.

Frame, PT. HIV disease in primary care. Prim Care. 2003; 30:205–237.

Mehrabi, M, Bagheri, S, Leonard, MK, Jr., et al. Mucocutaneous manifestation of cryptococcal infection: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005; 63:1543–1549.

Miller, EJ, Jr., Dodson, TB. The risk of serious odontogenic infection in HIV-positive patients: a pilot study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998; 86:406–409.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for adult and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo. nih. gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl. pdf.

Patton, LL. Hematologic abnormalities among HIV-infected patients: associations of significance for dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999; 88:561–567.

Ray, N, Doms, RW. HIV-1 coreceptors and their inhibitors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006; 303:97–120.

Schmidt, B, Kearns, G, Perrott, D, et al. Infection following treatment of mandibular fractures in human immunodeficiency virus seropositive patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995; 53:1134–1139.

Shanti, RB, Aziz, SR. HIV-associated salivary gland disease. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009; 21:339–343.

Sleasman, JW, Goodenow, MM. HIV-1 infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 111:S582–S592.

Tappuni, AR, Flemming, JP. The effect of antiretroviral therapy on the prevalence of oral manifestations in HIV-infected patients: a UK study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001; 92:623–628.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Examination

General. The patient is a mildly obese woman in mild distress secondary to pain.

Neurologic. Patient is alert and oriented to place, time, and person.

Pulmonary. The chest is clear on auscultation bilaterally.

Cardiovascular. Regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

Labs

The following laboratory study results were obtained for the current patient:

• Complete blood count: White blood cells 14,000/µl, hemoglobin 9.2 g/dl, hematocrit 29.2%, platelets 265,000/µl

• Chemistry: Sodium 145 mEq/L, potassium 5.6 mEq/L, bicarbonate 22 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen 48 mg/dl, creatinine 3.9 mg/dl, glucose 167 mg/dl, calcium 7 mg/dl, phosphate 5.2 mg/dl

• Coagulation studies: Prothrombin time 11 seconds, partial thromboplastin time 33 seconds, international normalized ratio 1.0

• Liver function tests: Aspartate aminotransferase 42 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 33 U/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 43 U/L, alkaline phosphate 34 U/L

• Urinalysis: 300 mg/dL proteinuria; no red blood cells, white blood cells, or casts

Complications

The development of uremic syndrome due to end-stage renal disease (often when the glomerular filtration rate is less than 10 ml/minute) is associated with a variety of symptoms (Table 15-5) and herald the urgent need for dialysis. This syndrome is due to the combined effects of the accumulation of various metabolites (not just urea). Other indications for dialysis include acidosis, electrolyte abnormalities, drug toxicity, and fluid overload. Thrombosis, hypotension, occlusion through blood pressure cuffs, and improper tucking of extremities may compromise the vascular access (arteriovenous fistulas, synthetic grafts, and central venous catheters) used to perform dialysis and should be avoided.

Table 15-5

Symptoms of Uremic Syndrome Due to End-Stage Renal Disease

| System | Symptoms |

| Central nervous | Irritability, insomnia, lethargy, seizures, coma |

| Musculoskeletal | Weakness, gout, pseudogout, renal osteodystrophy |

| Hematologic | Anemia, coagulopathy |

| Pulmonary | Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, pneumonitis |

| Cerebrovascular | Pericarditis, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, atherosclerosis |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Acid-base/volume | Hyperkalemia, volume overload (other electrolyte disturbances) |

| Endocrine | Hyperparathyroidism, hyperlipidemia, increased insulin resistance |

| Dermatologic | Pruritus, skin discoloration (yellow) |

Carrasco, LR, Chou, JC. Perioperative management of patients with renal disease. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2006; 18:203–212.

Coca, SG, Singanamala, S, Parikh, CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012; 81:442–448.

Susantitaphong, P, Altamimi, S, Ashkar, M, et al. GFR at initiation of dialysis and mortality in CKD: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012; 59(6):829–840.

Liver Disease

Labs

For the current patient, the following laboratory tests were obtained:

• Chemistry: Sodium 133 mEq/L, potassium 3.1 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen 48 mg/dl, creatinine 1.6 mg/dl, glucose 172 mg/dl, magnesium 1.0 mg/dl, bilirubin 1.3 mg/ dl, ammonia 67 mmol/L, albumin 2.2 mg/dl

• Complete blood count: White blood cells 4,500/µl, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dl, hematocrit 30.1%, platelets 62,000/µl

• Coagulation studies: Prothrombin time 17 seconds, partial thromboplastin time 43 seconds, international normalized ratio 1.5

• Liver function tests: Aspartate aminotransferase 141 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 84 U/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 45 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 51 U/L.

Complications

End-stage liver disease (ESLD) can be treated with liver transplantation, although most patients die of liver disease or are not eligible for transplantation. In 2002, the Mayo Clinic began to stratify ESLD liver transplant recipients with an objective calculator to determine the severity of liver dysfunction. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score can be used to predict morbidity and mortality in patients needing nonliver surgery. The MELD score is readily calculated using the patient’s INR, bilirubin and creatinine. The formula is available at the website www.mayoclinic.org/meld/mayomodel5.html. Elective nonliver surgery is acceptable in a patient with a MELD score below 10; a score between 10 and 15 necessitates careful assessment of risks and benefit; and a score above 16 effectively eliminates elective procedures. Our patient, despite a MELD score of 16, was a candidate for open reduction and internal fixation of his fractured mandible, because this is not elective surgery. However, elevated MELD scores are associated with increased perioperative morbidity and mortality. Successful liver transplant recipients have a functionally normal liver but are immunosuppressed to prevent graft rejection. This may result in an increase in both opportunistic and perioperative infections.

Kamath, PS, Wiesner, RH, Malinchoc, M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001; 33:464–470.

Muir, AJ. Surgical clearance for the patient with chronic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2012; 16:421–433.

O’Leary, JG, Yachimski, PS, Friedman, LS. Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2009; 13:211–231.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses