Management of cleft lip and palate

Nicky Kilpatrick

Introduction

Epidemiology

Clefts of the lip and cleft palate are fusion disorders that affect the midfacial skeleton. They are one of the most common congenital anomalies with a worldwide incidence of between 0.8 and 2.7 cases per 1000 live births. The incidence of clefting varies by region, gender, ethnicity and maternal characteristics. Racial differences are apparent with Native Americans having the highest incidence (followed by Maoris, Chinese, Anglo Saxons) and African-Americans the lowest.

Aetiology

Despite being common, the aetiology of many clefts of the lip/palate remains obscure. In addition to chromosomal abnormalities and teratogenic effects, there are over 500 recognized Mendelian syndromes associated with a cleft of the lip/palate. In many instances, specific genetic mutations have been identified, e.g. van de Woude syndrome (IRF6) and Treacher Collins (TCOF1). However, over 70% of clefts of the lip and palate and up to 50% of clefts of the palate only are apparently isolated anomalies. The aetiology of these non-syndromic forms of cleft is multifactorial and the relative genetic and environmental contributions remain unclear. Consequently, while it is understood that offspring and siblings of individuals with a cleft have a higher risk of having a cleft themselves this lack of clarity makes it difficult to give families accurate information regarding the recurrence risks or to offer informed genetic counselling.

Embryology

Orofacial clefts result from a failure of complete fusion between any of the independently derived facial primordia that form the orofacial complex. Development of the human face begins around day 22 with the migration of cranial neural crest cells (ectomesenchyme) from the dorsal region of the anterior neural tube into the facial region. On either side of the foregut, ectodermal swellings form five pairs of branchial (pharyngeal) arches that are derived from primitive gill or visceral arches of fish. These facial primordial establish during the 4th week of gestation, consisting of five distinct prominences:

• A pair of mandibular prominences develop into the lower jaw.

• A pair of bilateral maxillary prominences that result in the upper jaw.

The secondary palate protrudes as a medial outgrowth from the maxillary prominences and consists of neural crest-derived mesenchymal cells. The shelves grow vertically (downwards) initially from the bilateral maxillary processes during the 6th week. Growth of the embryo causes rotation and extension of the head, dropping the tongue that was lying in the nasal cavity into the mouth (stomodeum). At the same time, the palatal shelves elevate to the horizontal position above the tongue during the 7th week of gestation. Following elevation, the palatal shelves continue to grow towards each other during the 8th week until the epithelial surfaces covering the opposing palatal shelves meet and fuse at the midline to form the secondary palate. The epithelium breaks down allowing mesenchymal consolidation.

Events that disrupt the fusion may result in clefting:

Anatomy

Clefts of the lip and palate may be unilateral or bilateral, complete or incomplete. The presentation of clefting conditions can be categorized into the following groups:

Clefts of the lip and alveolus (primary palate)

The primary palate forms anterior to the incisive foramen. A cleft of the primary palate may vary from an incomplete cleft (forme fruste) to a minimal defect involving just the vermilion border, to a complete defect extending from the vermilion border to the floor of the nose with clefting of the alveolus. Even in the absence of a frank cleft of the bony alveolus there may be evidence of clefting in the form of a dental anomaly such as a missing or microdont lateral incisor (see Chapter 11). Clefts of the primary palate may be unilateral or bilateral.

Cleft lip and palate (CL/P)

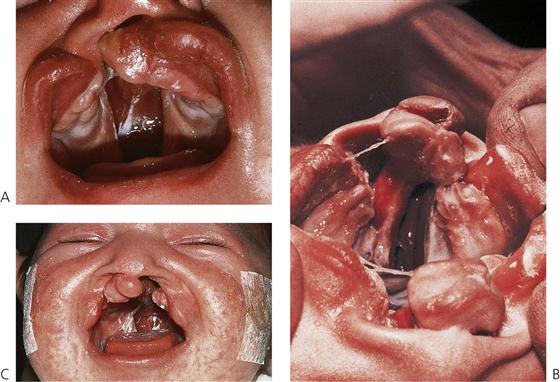

Varying degrees of clefting of the lip and palate can also exist; complete to incomplete, in a wide range of combinations; uni- and bilateral, symmetrical and asymmetrical. In complete clefts, a direct communication exists between the oral and nasal cavities on the cleft side (Figure 15.1A). There can be substantial variation in the degree of palatal shelf separation and while the maxillary arch form generally appears normal at birth, medial collapse of the maxillary segments occurs soon after.

Bilateral clefts of the lip and palate can be either symmetrical or asymmetrical. In the bilateral complete cleft lip and palate, both nasal chambers are in direct communication with the oral cavity. The palatal processes are divided into two equal parts and the turbinates are clearly visible within both nasal cavities. The nasal septum forms a midline structure that is firmly attached to the base of the skull but is fairly mobile anteriorly, where it supports the premaxilla and columella (Figure 15.1B). In these clefts, the premaxilla protrudes considerably forward of the facial profile and is attached to a stalk-like vomer and the nasal septum. The ‘lip’ component of the medial segment contains only collagenous connective tissue. It is, therefore, grossly deficient in bulk and lacks the features normally produced by muscle (Figure 15.1C).

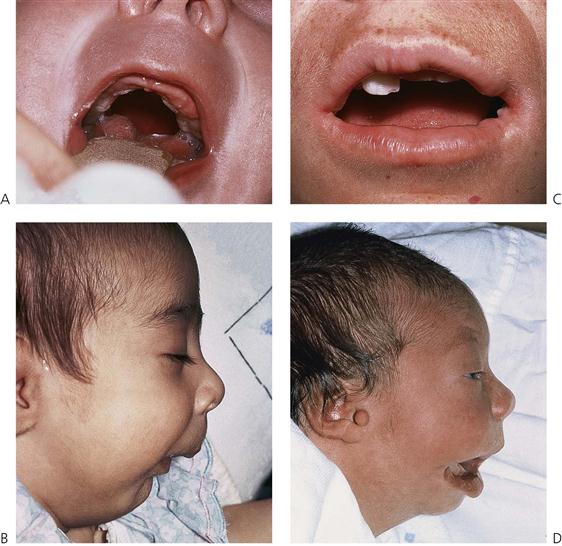

Cleft palate

A cleft of the palate may involve only the soft palate, both soft and hard palates, but almost never the hard palate alone. Deficiency of mucosa and bone are the main features of clefts of the hard palate (Figure 15.2). The cleft may extend forward from the uvula to varying degrees, from a bifid uvula (Figure 15.3) to a ‘V’-shaped cleft extending through the hard palate to the incisive foramen. Some babies have a ‘U’-shaped cleft of the palate that is described in ‘Robin sequence’ (Figure 15.2). Robin sequence is characterized by upper airway problems associated with a very small mandible and glossoptosis and is thought to be secondary to mandibular hypoplasia in the 1st trimester, which causes the tongue to sit high in the mouth and prevent fusion of the palatal shelves.

Submucous cleft palate

Clefting of the velum or soft palate can be ‘submucous’ where the mucous membrane remains intact, despite clefting of the underlying musculature. Submucous clefts of the palate occur in around 1 in 1200 live births, with only half of the cases having clinically significant symptoms.

Diagnosis

Clefting disorders are now increasingly diagnosed prenatally as part of routine ultrasound screening between 18 and 20 weeks in utero. The reported diagnostic accuracy of routine 2D ultrasonography in a low risk population varies between 9–100% for complete clefts of lip and palate but is much lower (0–22%) for clefts of the palate only (Maarse et al 2010). Much higher accuracy is achieved using 3D ultrasound but again isolated clefts of the palate often remain undetected. Prenatal screening provides knowledge of the impending birth of a baby with a cleft, which allows both the family and appropriate clinicians to prepare for this event.

Management of individuals with clefts of the lip and/or palate

Although surgery can correct many of the structural defects, affected individuals can still face a lifetime of functional, social and aesthetic challenges. In addition, there is growing evidence that individuals with CL/P may also have subtle neuropsychological and developmental deficits, which are associated with learning difficulties and other educational challenges. The care of these infants often starts antenatally and continues from birth through to adulthood and involves a large multidisciplinary team of clinicians. The specialties involved in this team vary greatly but usually include:

In addition, genetics, ophthalmology, neurosurgery, periodontics and implantology may be involved at different times. Such orofacial clefting places enormous burdens, both financial and psychosocial on, not just the individual themselves, but also their family and society more broadly.

While there is a lot of variation (and very little high-level evidence) in the sequencing and timing of treatment and the clinical techniques and interventions used, there are some commonly accepted aims and principles of treatment. The appropriate specialists (usually a specialist nurse and/or primary surgeon) within a cleft team aim to provide a rapid initial evaluation, often within hours of birth. Subsequent regular contact through either home visits or attendance at specialist cleft review clinics ensures that families are supported appropriately and social and psychological issues identified and resolved early. Treatment plans can then be formulated and implemented collaboratively by the multidisciplinary team in partnership with the families.

The goals of the treatment of a child with a cleft of the lip and/or palate are to restore both form (appearance) and function (especially speech and mastication), while optimizing an individual’s general health and well-being.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses