CHAPTER 15 Hospital Dental Services for Children and the Use of General Anesthesia

OBTAINING HOSPITAL STAFF PRIVILEGES

As active members of the hospital staff, dentists should be aware of the hospital’s bylaws, rules, regulations, and meetings. A copy of the bylaws should be obtained for easy reference. Fully understanding the responsibilities of staff membership will enable dentists to treat their patients within the established protocol of the institution. Most important, dentists should endeavor to provide the highest quality care within the specialty area for which they are trained. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry encourages the participation of pediatric dentistry practitioners on hospital medical-dental staffs, recognizes the American Dental Association as a corporate member of the Joint Commission, and encourages hospital member pediatric dentists to maintain strict adherence to the rules and regulations of the policies of the hospital medical staff.

INDICATIONS FOR GENERAL ANESTHESIA IN THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN

The safety of the patient and practitioner, as well as the need to diagnose and treat, must justify the use of general anesthesia. All available management techniques, including acceptable restraints and sedation, should be considered before the decision is made to use a general anesthetic. Crespi and Friedman cite several authors who agree in recommending that at least one or two attempts be made using conventional behavior management techniques or conscious sedation before general anesthesia is considered.1

PSYCHOLOGIC EFFECTS OF HOSPITALIZATION ON CHILDREN

Hospitalization is a frequent source of anxiety for children. According to King and Nielson, 20% to 50% of children demonstrate some degree of behavioral change after hospitalization.2 Separation of the child from the parent appears to be a significant factor in post-hospitalization anxiety, although other causes are also documented. Allowing the parent to stay with the child during the hospitalization, and especially to be present when the child leaves for and returns from surgery, can reduce anxiety for the child and parent alike.

According to Camm and colleagues, postoperative behavioral changes reported by mothers in a limited sample of children who received dental treatment with general anesthesia in a hospital were similar to those observed in children who received treatment under conscious sedation in a dental clinic.3 Mothers of children receiving dental treatment with general anesthesia in a hospital setting were found to experience more stress during the procedure. Ways to decrease these stresses include the following: providing a prior tour of the operating room facility, informing the parents of the status of the child during the procedure, and letting them know that “everything is all right.” Seventy-five percent of the children receiving general anesthesia exhibited some type of behavioral change. Positive changes included less fuss about eating, fewer temper tantrums, and better appetite. Negative changes included biting the fingernails, becoming upset when left alone, being more cautious or avoiding new things, staying with the parent more, needing more attention, and being afraid of the dark. Ways to minimize negative changes include (1) involving the child in the operating room tour, (2) allowing the child to bring along a favorite doll or toy, (3) giving preinduction sedation, (4) providing a nonthreatening environment, (5) giving postprocedure sedation as needed, and (6) allowing parents to rejoin their children as early as possible in the recovery area.

Peretz and colleagues concluded that children treated for early childhood caries under general anesthesia or under conscious sedation at a very young age behaved similarly or better in a follow-up examination approximately 14 months after treatment than at their pretreatment visit, as measured by the Frankl scale and by the “sitting pattern.”4

Fuhrer and colleagues found children were more likely to exhibit positive behavior at their 6-month recall appointment following dental treatment for childhood caries under general anesthesia versus those treated under oral conscious sedation.5

OUTPATIENT VERSUS INPATIENT SURGERY

Good patient selection is an important criterion of a successful outpatient surgery program. A young child or adolescent who requires a general anesthetic and is free of any significant medical disorders (i.e., is categorized as class I or II on the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification—see Box 14-1) can be considered a candidate for outpatient surgery. Certain patients with well-controlled chronic systemic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, and congenital heart disease can also be considered for outpatient anesthesia following prior consultation with an anesthesiologist.

When the outpatient surgery is planned, the child undergoes a complete preoperative evaluation, including a comprehensive medical history and physical examination, anesthesia assessment, and limited hematologic evaluation. Many medical facilities allow this preadmission preparation to be performed outside of the medical outpatient treatment facility. Biery and associates suggest that routine laboratory tests, such as urinalysis and complete blood count with indices and electrolyte levels, are not cost effective nor are they necessary for patients categorized as ASA class I in whom the prior complete medical history and physical examination was unremarkable.6

The dentist will be more responsible for team communication, physical assessment, management, and postoperative evaluation for outpatient procedures under general anesthesia than for inpatient procedures. Ferretti reported that pediatric outpatient general anesthesia patients must have reliable parents or guardians to qualify for treatment.7 For example, the parents must have transportation available to return the child to the hospital in case postoperative complications develop at home.

MEDICAL HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

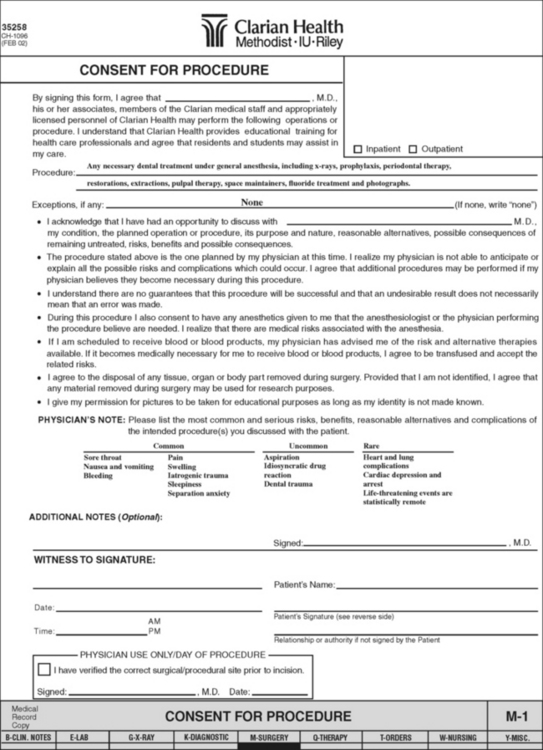

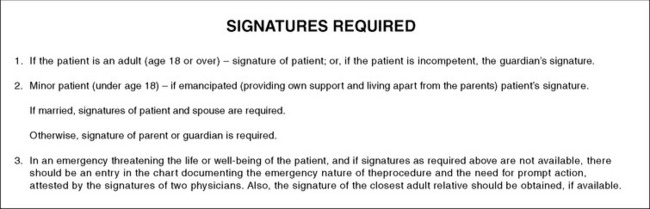

Once the decision has been made that a general anesthetic would be preferable for a pediatric patient, the dentist should evaluate the child’s medical history, the current medical status, and the possibility of complications resulting from the procedure. This risk assessment process is discussed in Chapter 14, and the patientclassification categories are shown in Box 14-1. The parents should be told of any potential complications, and their informed consent must be obtained (Fig. 15-1).474

Intraoperative medical complications of dental patients with and without disabilities undergoing general anesthesia have been reported at 0% to 1.4%. In a survey of 200 pediatric dental general anesthesia cases, Enger and Mourino indicated that the most common postoperative complications following general anesthesia in children younger than the age of 5 years were vomiting, fever, and sore throat.8 Treatment of complications consisted of administration of antiemetic medications for nausea with vomiting, ice chips for sore throat, and acetaminophen (Tylenol) for fever postoperatively. Bradley and Lynch found that no significant long-term complications resulting from anesthesia or operative procedures were observed in 100 disabled and nondisabled patients.9

The Joint Commission requires that all patients admitted to a hospital or treated under general anesthesia as an outpatient have a physical examination performed by a physician or qualified dentist. The child’s physician must therefore be consulted for the completion of a comprehensive medical history and physical examination (Box 15-1). If the physician is not a member of the hospital staff, a staff physician should complete the medical history and physical examination before admission. The dentist should perform a thorough intraoral examination and submit a record of the findings together with a summary of the child’s dental history and the reason for admission (Box 15-2). The hospital must be notified to reserve an appropriate surgical suite and a bed for the child. Two weeks before admission or an outpatient dental surgery appointment, a letter containing general instructions concerning the procedure, results of the dental examination, and pertinent dates and times should be mailed to the parents.

Box 15-1 Components of the Pediatric Medical History and Physical Examination for Admission to the Hospital

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses