15

Adverse drug reactions and interactions

Adverse drug reactions

These reactions are unwanted effects arising from a patient’s medication. Such reactions can be conveniently classified as type A (Augmented reactions) or type B (Bizarre reactions).

Type A reactions are the result of an exaggerated but otherwise normal pharmacological action of a drug given in the usual therapeutic dose. An example would include prolonged bleeding due to the antiplatelet action of aspirin. These reactions are largely predictable on the basis of a drug’s known pharmacology.

In contrast, type B reactions have totally aberrant effects that are not to be expected from the known pharmacological actions of a drug when given in the usual therapeutic doses to a patient whose body handles the drug in the normal way. Examples include hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin, angioedema arising from ACE inhibitors and drug-induced gingival overgrowth.

Oral and dental structures are frequently the sites of adverse drug reactions. Targets include salivary glands, oral mucosa, periodontal tissues, teeth and alveolar bone.

Salivary glands

Systemic drug therapy can have a profound effect upon salivary gland function. Drug-induced xerostomia is perhaps the most widespread oral adverse drug reaction seen in dentistry. Other adverse drug reactions impacting upon salivary glands and function include sialorrhoea, gland swelling, and pain and taste disturbances.

Drug-induced xerostomia

The salivary glands are under the control of the autonomic nervous system and hence their function can be affected by a variety of drugs. Most of the drugs that reduce salivary flow do so by competing with acetylcholine release at the parasympathetic effector junction. Some 400 drugs have been implicated in causing xerostomia, and a list of the different categories with examples is shown in Table 15.1.

Oral problems associated with xerostomia include impaired speech, eating and swallowing. Patients become more susceptible to oral infections, especially those caused by Candida albicans. For dentate patients, the reduced salivary flow rate and hence its reduced buffering capacity increases the risk of dental caries, especially root caries. Other oral problems associated with xerostomia include an increased risk of angular cheilitis, mucosal ulceration and development of leukoplakia. For the edentulous patient, drug-induced xerostomia produces significant problems with denture retention.

Management of drug-induced xerostomia

For the most part, patients learn to adapt and cope with their reduced salivary flow. Local measures such as frequent sips of water or chewing sugar-free gum may help to alleviate some of the problems. A variety of salivary substitutes are commercially available, but one which contains fluoride would be beneficial in reducing the risk of root caries.

Pilocarpine 50 mg (a muscarinic antagonist) has been shown to be useful in the management of xerostomia. The drug does have unwanted effects including increased sweating, headache, nausea, urinary frequency and palpitations. Such unwanted effects may affect compliance.

Many of the xerogenic drugs are taken once a day, and patients may prefer to take such medications first thing in the morning. This does cause the maximum xerogenic effect to occur during the day and has maximum impact upon eating and swallowing. Switching the timing of the medication, if appropriate, to night time will reduce the impact of the drug’s xerostomic effect.

Table 15.1 Categories of drugs and examples that can cause xerostomia

| Category | Example |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Amitriptyline |

| Muscarinic receptor antagonist | Oxybutynin |

| α-Receptor antagonist | Terazosin |

| Antipsychotics | Phenothiazines |

| Lithium | |

| Diuretics | Furosemide |

| Histamine H1 receptor blockers | Chlorphenamine |

| Histamine H2 receptor blockers | Cimetidine |

| Central antihypertensives | Moxonidine |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Lisinopril |

| Serotonin antagonists | Fluoxetine |

| Noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors | Reboxetine |

| Dopamine re-uptake inhibitors | Bupropion |

| Appetite suppressants | Fenfluramine |

| Phentamine | |

| Systemic bronchodilators | Tiotropium |

| Opioids | Morphine |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Omeprazole |

| Cytotoxic drugs | 5-Fluorouracil |

| Retinoids | Isotretinoin |

| Anti-HIV drugs | Didanosine and HIV protease inhibitors |

| Antimigraine drugs | Rizatriptan |

| Decongestants | Pseudoephedrine |

Drug-induced sialorrhoea

Hypersalivation or sialorrhoea is often recognised as drooling. The latter is caused either by an increase in saliva flow that cannot be compensated by swallowing or by impaired swallowing that cannot manage normal or even reduced amounts of saliva. The drug most frequently associated with sialorrhoea is the antipsychotic agent, clozapine. This drug is one of the first-line agents in the management of schizophrenia, thus switching medication may not be an option for the management of this unwanted effect.

Drug-induced pain and swelling of the salivary glands

Several drugs have been cited as causing pain and swelling mainly in the parotid gland, in particular, drugs which can either concentrate in the gland or be accidentally aspirated into it. Iodine, which is used as a radiographic contrast medium, does concentrate in the parotid gland up to 100-fold the levels in plasma. Parotid swelling is a rare unwanted effect arising from chlorhexidine mouthrinsing. The swelling appears to subside spontaneously within a few days after discontinuing use. The clinical features have the appearance of mechanical obstruction of the parotid duct. It is suggested that overvigorous mouthrinsing may create a negative pressure in the parotid and aspiration of chlorhexidine into the gland. Patients should be instructed to be less vigorous with their mouthrinsing so as to avoid this unwanted effect.

Drug-induced taste disturbances

Many drugs induce abnormalities of taste either via reducing serum zinc levels (zinc is essential for taste acuity) or by a direct interaction with proteins or taste bud receptors. The alteration in taste may be simply a blunting or decreased sensitivity in taste perception (hypogeusia), a total loss of the ability to taste (ageusia) or a distortion in perception of the correct taste of a substance, e.g. sour for sweet (dysgeusia).

Drugs that contain a sulfhydryl group (e.g. penicillamine and captopril) are common causes of taste disturbances. The sulfhydryl group binds with proteins on taste buds and reduces taste acuity. Loop diuretics (e.g. furosemide) and to a lesser extent thiazide diuretics (e.g. bendroflumethiazide) are a cause of taste disturbances. Both types of diuretic deplete the body of a variety of metallic salts including zinc. Of particular concern to the dental profession is the relationship between chlorhexidine and taste disturbances. Following a chlorhexidine rinse, the appreciation of sweetness is affected first, followed by saltiness and bitterness. This unwanted effect is compounded by repeated use. The mechanism of chlorhexidine-induced taste disturbances may be related to the drug’s ability to bind to proteins on the taste buds.

Oral mucosa and tongue

A variety of drugs can cause or exacerbate well-recognised conditions of the oral mucosa and tongue. Such conditions can be classified by specific lesions, and include drug-induced vesiculobullous conditions, oral ulceration, lichenoid eruptions and other white lesions of the oral mucosa, and discoloration of the oral mucosa.

Drug-induced vesiculobullous lesions

Such conditions include erythema multiforme (which also includes Stevens–Johnson syndrome), mucous membrane, pemphigoid and pehmpigus vulgaris (Chapter 11). Drugs that are frequently cited as causal in these various vesiculobullous conditions are shown in Table 15.2.

Table 15.2 Categories of drugs that have been cited as causing vesiculobullous lesions

| Category | Example |

| Analgesics | Aspirin, diclofenac, diflunisal, mefenamic acid, piroxicam, ibuprofen |

| Antibiotics | Clindamycin, streptomycin, tetracyclines, vancomycin, co-trimoxazole |

| Calcium channel blockers | Diltiazem, nifedipine, verapamil, amlodipine |

| Antiepileptic | Carbamazepine, phenytoin |

| Antifungals | Fluconazole, griseofulvin |

| Diuretics | Hydrochlorothiazide, furosemide |

| Antidiabetics | Chlorpropamide, tolbutamide |

| Hormones | Mesterolone, progesterone |

| Miscellaneous | Quinine, retinol, mercury, omeprazole, zidovudine |

Lichen planus

Oral lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory oral mucosal disease of unknown aetiology. The term lichenoid drug eruptions can be used in two senses. First, drug eruptions similar or identical to lichen planus and, secondly, drug eruptions which do not necessarily appear like lichen planus, but have histological features very like this condition. A list of drugs that have been associated with lichenoid eruptions are shown in Table 15.3.

In addition to systemic medication, lichenoid reactions can be associated with dental materials. Amalgam, especially mercuric chloride, is the material most frequently cited. For some patients, replacing their amalgam restorations may result in an improvement of their oral lesions.

Other drug-related white lesions of the oral mucosa

Such lesions include candidosis, hairy leukoplakia and leukoplakia. Many of these conditions arise in immunosuppressed organ transplant patients and are secondary to a combination of ciclosporin, azathioprine and prednisolone.

It should also be emphasised that these types of lesions can be found in HIV patients, further underlying the aspect of immunosuppression in their pathogenesis.

Drug-induced discoloration of the oral mucosa

Many food substances and beverages can stain the oral mucosa, albeit temporarily. Apart from food, the most common discoloration of the tongue is known as black hairy tongue. This results from hypertrophy of the filiform papillae, which may grow up to 1 cm in length. Oral penicillins and other topical antimicrobials can cause black hairy tongue. Brushing the tongue may reduce this unwanted effect.

Table 15.3 Drugs that have been associated with lichen planus

| ACE-1 inhibitors, e.g. captopril | Lorazepam |

| Antimalarials | Mercury (amalgam) |

| β-Adrenoceptor blockers, e.g. propranolol | Metronidazole |

| Carbamazepine | NSAIDs |

| Chloral hydrate | Oral contraceptives |

| Chlorpropamide | Penicillins |

| Cinnarizine | Phenytoin |

| Dipyridamole | Quinine |

| Furosemide | Rifampicin |

| Ketoconazole | Streptomycin |

| Lincomycin | Sulfonamides |

| Lithium | Tetracyclines |

| Thiazide diuretics | |

| Tolbutamide |

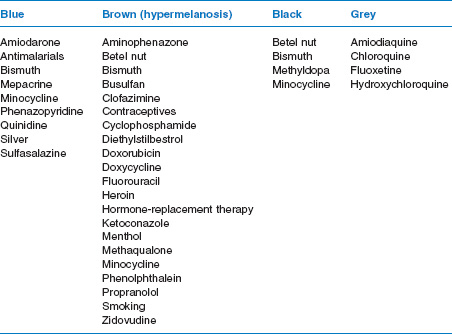

A common cause of drug-induced discoloration of the oral mucosa relates to a drug enhancement of melano-genesis. Hormones are the main drug implicated in this unwanted effect. Other details of drug-induced discoloration of the oral mucosa, together with possible underlying mechanisms, are shown Table 15.4.

Drug-induced oral ulceration

A number of drugs can cause a wide range of ulcerative lesions of the oral mucosa. These range from local irritants that cause oral burns, drug-related aphthous-type ulceration and fixed drug eruptions.

Local irritants

The best known example is the so-called ‘aspirin burn’ arising from patients placing an aspirin tablet against a tooth with a view to relieving their pain. Such a practice has no benefit in the management of toothache and the corrosive action of the acidic aspirin can result in a fairly large area of ulceration. Similar burns have been reported following the use of proprietary toothache solutions.

Cocaine abusers have been reported to suffer from extensive oral ulceration when the drug is applied topically. Often cocaine abusers or ‘drug pushers’ rub the cocaine powder into the attached gingivae, often in the upper premolar area. Since cocaine is a powerful topical anaesthetic, this local application onto the oral mucosa is used to ‘test’ the purity of the substance. The ulceration is probably due to the intense vasoconstrictive properties of cocaine.

Other drugs can act as local irritants including potassium chloride, isoprenaline, pancreatin and ergotamine tartrate. Damage results when the drug is retained in the mouth for too long, e.g. sucking the tablets as opposed to swallowing them.

Table 15.4 Drugs that can cause discoloration of the oral mucosa

Drug-related aphthous-type ulceration

Aphthous ulceration, often referred to as recurrent aphthous ulceration (RAU), is a common condition that is characterised by multiple, recurrent, small, round or ovoid ulcers (Fig. 15.1). The aetiology of RAU is for the most part unknown, but several risk factors have been identified.

Systemic medication can cause RAU, and drugs implicated include certain NSAIDs, β-adrenoceptor blockers, captopril (an ACE-1 inhibitor), nicorandil (a potassium channel activator), protease inhibitors and the new immunosuppressant agent, tacrolimus.

Diagnosis of drug-induced RAU can be problematic. The ulcers usually occur and then disappear with discontinuation of the drug. To confirm the cause and effect requires rechallenging the patient with the same drug. This does raise ethical issues. The mechanisms of drug-induced RAU remain uncertain.

Fixed drug eruptions

Such eruptions often occur as repeated ulcerations at the same site in response to a particular drug or other compound. They are essentially type IV or a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. When the ulceration is due to a systemic medication, then the term fixed drug eruption is appropriate. If the ulceration is from local contact, then it is more appropriate to refer to this as contact stomatitis. Table 15.5 lists the drugs commonly cited as causing fixed drug eruptions.

Figure 15.1 Drug-related aphthous ulceration.

Table 15.5 Some drugs that have been implicated in causing fixed drug eruptions

|

|

|

|

|

Many compounds have been cited as causing contact stomatitis. These include cosmetics, chewing gum, ingredients of toothpaste and certain dental materials. Metals are frequently implicated, especially nickel-containing alloys. The increasing fashion of tongue and lip piercing has resulted in a rise in contact dermatitis since many of the lip and tongue decorations contain nickel.

Dental structures

Systemic drug therapy can affect the dental structures, although this is mainly an indirect effect mediated by a drug-induced alteration in the oral environment. Considered under this heading are drugs that affect dental structures and the problems of sugar-based medicines.

Tooth development

The antiepileptic drug, phenytoin, can cause abnormalities in the roots of the teeth. Defects include shortening of the root, root resorption and an increased deposition of cementum. The mechanism of phenytoin-induced root abnormalities is uncertain, but may be related to the drug inhibiting vitamin D metabolism or PTH production.

Intraligamentary injections of lidocaine and prilocaine are cytotoxic to the enamel organ and will interfere with amelogenesis. Chemotherapeutic agents used in treatments of childhood malignancies can interfere with the formation of dental tissues. Such drugs can disrupt the development of the enamel organ and produce a number of dental abnormalities including failure of the tooth to develop, microdontia, hypoplasia, enamel opacities and impaired root development.

Drug-induced staining of the dental structures

Chlorhexidine

Staining of the teeth, restorations and dentures is the most common problem associated with chlorhexidine usage. The extent and severity of the staining does appear to be related to concentration. Less staining is reported to occur after use of 0.12% solution compared with the 0.2% solution.

Chlorhexidine-induced staining is enhanced by dietary factors, especially foods and drink that contain high levels of tannins, e.g. red wine, tea and coffee. The primary site for discoloration appears to be the acquired pellicle, which suggests that salivary proteins (the source of the pellicle) play an important role in the chlorhexidine-induced staining process. Removal of chlorhexidine staining can be problematic and often requires professional cleaning.

Tetracyclines and other antibiotics

The possible effects of tetracyclines on the developing teeth are well established. Immediately after absorption, tetracyclines are incorporated into the calcifying tissues, which become a permanent feature in the teeth. For the most part, the discoloration is grey, but brownish-yellow discoloration can occur with certain tetracycline preparations. Tetracycline-induced discoloration only occurs during the formative stages of tooth development and hence these drugs should be avoided during this time. Ciprofloxacillin has also been reported to cause a greenish discoloration of the teeth.

Sugar-based medicines

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses