Chapter 14

Xerostomia

Jadwiga Hjertstedt

Department of Clinical Services, Marquette University School of Dentistry, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Introduction

Xerostomia (dry mouth) is a subjective sensation of oral dryness and it may be associated with salivary gland hypofunction (SGH), and changes in salivary composition. It is a very common complaint among older adults but it is not a normal part of the aging process (Heft & Baum, 1984). Dry mouth is often neglected or unrecognized by some practitioners due to a variety of reasons such as diverse symptom presentation, patients not reporting due to an unawareness of its consequences to oral health, and practitioners being more focused on restorative needs of their patients considering these as more urgent or important. Nonetheless, clinicians need to have a good understanding of this condition and recognize its etiology, signs, and symptoms in order to recommend the most effective treatment to prevent oral health complications and improve their patients’ overall well-being and quality of life.

Role of saliva and functions of salivary components

An adequate amount of saliva is vital for maintaining oral health and for overall well-being. Saliva with its components (over 300 proteins, peptides, and electrolytes) plays an essential role in the maintenance of healthy soft and hard oral tissues as well as overall oral comfort (Dawes, 2008). The unpleasant symptoms reported by patients who experience xerostomia are the best evidence of how important saliva is to quality of life and serve as reminders of saliva’s important and versatile properties. Saliva has several protective functions affecting the oral mucosa and teeth. The salivary mucins lubricate and protect mucous membranes by coating and enhancing elasticity. Several proteins such as lysozyme, lactoferrin, histatins, cystatins, and secretory immunoglobulins have broad antimicrobial activity with the overlapping defensive systems. Together they prevent oral microorganisms’ aggregation and adherence; the proteins also inhibit microbial growth. Additionally, the bicarbonate/carbonate buffer system stabilizes intraoral pH by neutralizing acids which, in combination with certain proteins coating tooth enamel, is essential in the remineralization process thus protecting the dentition from dental caries (van Nieuw Amerongen et al., 2004). In addition, saliva facilitates speech and has several food intake-related functions. It assists with chewing activities, bolus formation, and digestion of starches (amylase) and fats (lipase), as well as aids in swallowing and taste mediation (Kaplan & Baum 1993).

Xerostomia has been called the “invisible” oral disease. Both patients and clinicians take saliva for granted and usually recognize the importance of its presence by the sequellae of its absence; therefore, it is important to recognize clinical signs and symptoms of xerostomia and/or SGH and to elucidate its cause. By doing so, clinicians may offer the patient recommendations and interventions that will prevent deleterious effects of hyposalivation, alleviate discomfort, and enhance a person’s quality of life.

Defining and recognizing xerostomia and SGH

Although xerostomia and SGH share common causes and seem to be interrelated, they refer to two separate entities. Xerostomia is the subjective sensation of dry mouth; therefore, patients themselves are its best “diagnosticians.” It should be differentiated from SGH or hyposalivation, which is an objective finding determined by measuring salivary gland output. The accepted reference values for hyposalivation are <0.1 ml/minute for unstimulated whole saliva (UWS) and <0.5 ml/min for stimulated whole saliva (SWS) (Dawes, 1996). These cut-off flow rates, however, do not account for variations based on factors that may affect salivary output such as degree of hydration, gender, circadian rhythms, gland size, medications, and age, among others.

Patients with xerostomia and/or SGH experience a variety of oral and nonoral symptoms (Närhi, 1994; Sreebny et al., 1989;) which may vary somewhat in nature, duration, and intensity among individuals. Common oral complaints associated with xerostomia include the sensation of a dry sticky mouth and tongue, thick saliva, mouth soreness, altered taste, increased thirst, and difficulty with speaking, eating, and swallowing (Table 14.1). Diets consisting of dry and spicy foods exacerbate problematic swallowing. Additionally, the need to drink in order to swallow when eating particularly dry foods is common, and it is known as the cracker sign, associated with the experience of eating dry crackers. Patients with xerostomia who wear removable prosthesis report several problems related to dry mouth including impaired denture retention, mouth soreness, and fungal infections (Turner et al., 2008).

Table 14.1 Subjective symptoms and clinical findings associated with xerostomia and/or salivary gland hypofunction

| Oral symptoms | Nonoral symptoms |

|

|

| Clinical findings and consequences of salivary gland hypofunction | |

|

|

These oral-related symptoms may lead to changes in eating habits including selection and avoidance of certain foods. For older adults social interaction with friends and family is a major aspect of their overall well-being. Since food plays an important role in the feeling of connecting with relatives, friends, and culture, xerostomia-associated oral symptoms may be very upsetting and frustrating, and ultimately may adversely affect their quality of life and contribute to social isolation. In addition, avoidance of certain foods may compromise the nutritional status in the geriatric population (Rhodus & Brown, 1990). Patients with xerostomia and SGH may also present with several nonoral symptoms such as dry skin and throat; dry, itching eyes and blurred vision; as well as vaginal itching and fungal infections (Table 14.1).

Dry mouth is a difficult and complex issue, with many questions still unanswered. The reasons for the complexity surrounding xerostomia will be discussed in this chapter. While xerostomia is most commonly linked to SGH, not all patients complaining of oral dryness have abnormally low salivary flow rates (Sreebny & Valdini, 1988; Thomson et al., 1999). Similarly, not all patients with SGH complain of dry mouth sensation. This may possibly be explained by the fact that patients first begin to experience symptoms of dry mouth when their unstimulated salivary volume has decreased by approximately 40–50% (Dawes, 1987).

Because hyposalivation has the potential to lead to significant deterioration of oral health including rapidly developing cervical and root caries, erosion, mucosal lesions, and opportunistic infections to name a few, it is imperative to properly identify patients with suspected SGH. The clinician should elicit responses to follow-up questions about their symptoms from those patients who complain of continual oral dryness. Positive responses to questions such as those listed below have been shown to be predictive in identifying patients with hyposalivation (Fox, 1996):

- Do you sip liquids to aid in swallowing dry foods?

- Does your mouth feel dry when eating a meal?

- Do you have difficulties swallowing any foods?

- Does the amount of the saliva in your mouth seem to be too little, too much, or you don’t notice it?

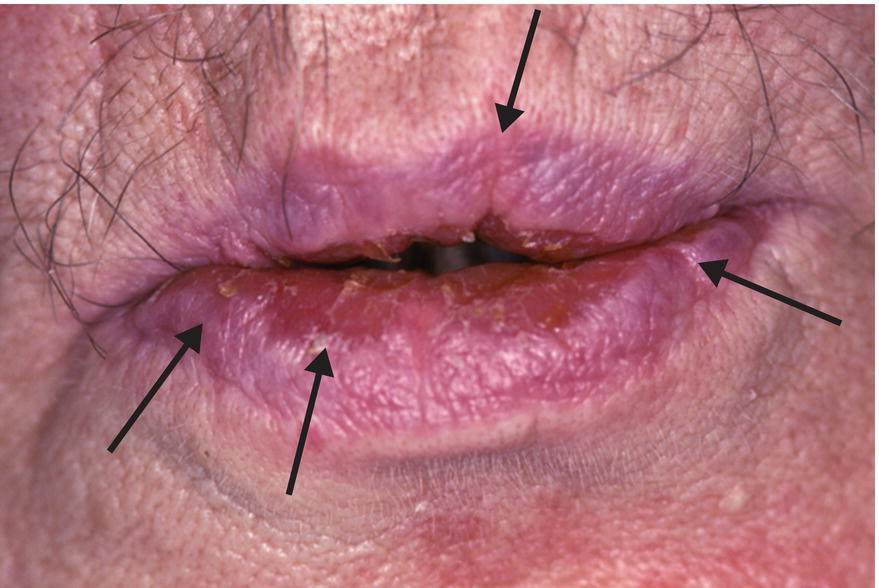

Additionally, several extraoral and intraoral findings identified during oral examination should alert the astute clinician to consider SGH in a differential diagnosis (with or without xerostomia) (Table 14.1). Extraoral signs frequently include: dry, cracked lips (Fig. 14.1) often with redness in the corners of the mouth suggesting angular cheilitis. Some patients (including those with Sjögren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis or viral infections) may have unilateral- or bilaterally enlarged parotid or submandibular glands that may or may not be tender on palpation. In some instances, salivary gland palpation will yield very little or no saliva. The expressed secretion may be more viscous than watery. Intraoral findings through visual inspection may reveal: dry, pale mucous membranes; reddened, fissured, and often a depapillated tongue (Fig. 14.2); and decreased or absent pooling of saliva on the floor of the mouth. One simple objective method to identify patients with SGH is whether the examiner’s gloved finger, a dental mirror, or a tongue blade sticks to the cheek during retraction.

Figure 14.1 Dry, cracked (arrows) lips in an elderly patient with medication-induced xerostomia.

Courtesy of Dr. Ralph H. Saunders, URMC, Rochester, NY.

Figure 14.2 Dry, red and depapillated, fissured tongue.

Courtesy of Dr. Ralph H. Saunders, URMC, Rochester, NY.

The most deleterious consequence of hyposalivation (with or without xerostomia) is the increased risk of rapidly progressive dental caries. Patients with severe SGH often present with rampant new or recurrent caries lesions that are often present on atypical surfaces such as cervical margins or incisal edges of the mandibular anterior teeth. Older adults with remaining teeth are a particularly vulnerable group. They are at significant risk for root caries (Fig. 14.3) because of exposed root surfaces from gingival recession as well as their compromised ability (i.e., impaired manual dexterity, sensory and cognitive deficits) to maintain good oral hygiene.

Figure 14.3 Root caries, plaque accumulation and dry erythematous oral mucosa due to medication-induced dry mouth.

Courtesy of Dr. Ralph H. Saunders, URMC, Rochester, NY.

Other common intraoral findings with SGH in older adults include increased plaque accumulation and frequent oral mucosal yeast infections primarily resulting from Candida albicans (Fig. 14.4). Together these extraoral and intraoral findings are valid indicators of hyposalivation (Navazesh et al., 1992) and stand as evidence to the importance of saliva for healthy soft and hard oral structures.

Figure 14.4 Erythematous, dry palatal mucosa (mucositis) with white plaques indicative of an opportunistic fungal infection caused by Candida albicans.

Courtesy of Dr. Ralph H. Saunders, URMC Rochester, NY.

Prevalence

Dry mouth is a common patient complaint, particularly among the elderly. Reviews of studies on the prevalence of xerostomia show that approximately 20% of the general adult population and 30% of those aged 65 and older report symptoms of oral dryness (Orellana et al., 2006; Ship et al., 2002). The reported estimates from studies on xerostomia prevalence have shown rates ranging from 0.9 to 64.8% with generally higher rates for women and for those in nursing homes (Handelman et al., 1989; Locker, 1995). The considerable variability in prevalence rates may be explained by lack of uniform methodology to measure and collect data. For example, inconsistent definition of xerostomia, varying content, and number of questions asked in the questionnaires, and use of small convenience study samples may affect reported prevalence rates (Orellana et al., 2006; Thomson, 2005). Understandably, nearly all patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and those who received radiotherapy for head and neck cancers report xerostomia (Chambers et al., 2007; Fox et al., 2000).

Similarly, studies conducted on prevalence of the SGH have shown significant variability, mainly due to the inconsistent measurement standards such as cut-off measurement values used for defining hyposalivation (Nederfors, 2000). Studies investigating concurrent prevalence of xerostomia and SGH within the same sample found much lower rates (ranging from 2 to 5.7%) of both conditions compared to rates reported separately (Bergdahl, 2000; Hochberg et al., 1998; Thomson et al., 1999). This finding supports the notion that these are two discrete conditions and further research is needed to explain the complex relationship between xerostomia and SGH.

Effect of aging on salivary glands and flow rates

There are significant age-related structural changes affecting all major and minor salivary glands. The reported histologic changes include significant acinar atrophy, with the acinar cells being replaced by fat, connective tissue, and duct-like epithelial structures (Scott et al., 1987; Waterhouse et al., 1973). These changes affect men and women similarly (Azevedo et al., 2005).

In the past it was the general belief that dry mouth is a natural part of aging. This notion was based on the fact that early studies found age-related changes in salivary glands and lower salivary flow rates among older adults when compared to younger individuals. These studies, however, had methodologic flaws, such as cross-sectional designs, and did not control for medication use nor health status (Becks & Wainwright, 1943; Bertram, 1967; Gutman & Ben-Aryeh, 1974).

Contrary to the past assumption that xerostomia is a normal part of aging, more recent data on changes in salivary glands function indicate that they retain their secretory capacity with aging. Prospective longitudinal studies conducted on healthy older adults consistently demonstrated no age-related changes in both unstimulated and stimulated secretions from parotid glands (Heft & Baum, 1984; Ship et al., 1995). Reports from studies on the flow rates from submandibular/sublingual and minor salivary glands provide conflicting results of reduced secretions (Pedersen et al., 1985) or no changes in salivary output with aging (Ship et al., 1995; Tylenda et al., 1988).

The retained overall functional capacity, despite age-related acinar atrophy, has been explained by the remaining adequate secretory reserve in salivary glands to compensate for some losses without causing dry mouth symptoms in healthy unmedicated older adults (Ghezzi & Ship, 2003). Therefore, complaints of dry mouth and/or SGH in older adults are likely to be caused by factors other than aging.

Etiology of xerostomia and/or SGH

Patients who present with complaints of dry mouth or clinical evidence of reduced salivary flow require careful assessment for possible etiologic factors in order to select appropriate interventions to prevent oral complications. Xerostomia and/or SGH have been linked to several different origins such as medications, radiation therapy to the head and neck, underlying systemic disease, and behavioral as well as other local factors. These factors will be discussed in the sections that follow.

Medication use

The predominant cause of dry mouth is the use of medications; both prescription and nonprescription. Older adults are the primary consumers of medications and this may explain why dry mouth complaints are far more common among them than among younger individuals. More than 500 commonly prescribed and over-the-counter drugs are associated with xerostomia or reduced salivary flow (Sreebny & Swartz, 1997). The agents that are most frequently implicated in dry mouth symptoms and reduced salivary output have anticholinergic properties that reduce the volume of serous saliva or have a sympathomimetic mechanism of action that makes saliva more viscous. Table 14.2 lists examples of common xerogenic drugs and their classes that include: antihistamines, anticholinergics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, antihypertensive agents, and diuretics among others. It is worth noting that certain drugs such as loop diuretics and inhaled medications may cause xerostomia without any adverse effects on salivary secretion (Atkinson et al., 1989). The prevalence and severity of dry mouth symptoms have been linked to the duration of use and the number of medications that an individual is taking. Polypharmacy, or the use of multiple medications, and the interaction between these medications has been shown to increase the incidence of xerostomia and SGH in the elderly because of the cumulative effects of combining drug therapies in an individual with multiple systemic problems (Thomson et al., 2000, 2006). Increased number of medications has also been associated with reduction in stimulated and unstimulated saliva flow rates (Wu & Ship 1993). Moreover, older adults who take multiple medications report more severe and longer-lasting symptoms of xerostomia than do younger individuals (Patel et al., 2001).

Table 14.2 Examples of frequently used medications causing xerostomia

| Classification (by therapeutic/pharmacologic category) | Generic name | Brand name |

| Analgesics (opioids and nonopioids) | Hydrocodone/acetaminophen | Anexia®; Dolacet®; Hydrocet®; Hydrogesic®; Vicodin® |

| Propoxyphene | Darvon® | |

| Analgesics (NSAIDS) | Ibuprofen | Advil®, Excedrin IB®, Ibuprin®, Motrin®, Nuprin® |

| Antianginals (nitrates) | Isosorbide | Isordil® |

| Antianxiety/ sedative/ hypnotics | ||

| Benzodiazepines (sedatives) | Alprazolam Diazepam Clonazapam Lorazepam Oxazepam |

Xanax® Valium® Klonopin® Ativan® Serax® |

| Benzodiazepines (hypnotics) | Temazepam | Restoril® |

| Anticonvulsants | Gabapentin | Neurontin® |

| Antidepressants | ||

| Tricyclic

Tetracyclic Atypical |

Amitriptyline Doxepin Maprotiline HCL Paroxetine Sertraline Escitalopram Fluoxetine Trazodone HCL |

Elavil® Sinequan® Ludiomil® Paxil® Zoloft® Lexapro® Prozac® Desyrel® |

| Antiarrhythmics | Procainamide Disopyramide |

Pronestyl® Norpace® |

| Antihistamines | Cetirizine HCL Diphenhydramine Fexofenadine HCL Loratadine |

Zyrtec® Benadryl® Allegra® Claritin® |

| Antihypertensives | ||

| Beta-adrenergic antagonists | Atenolol Metoprolol succinate |

Tenormin® Toprol-XL®; Lopressor® |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Lisinopril | Prinivil®; Zestril® |

| Calcium channel blockers | Amlodipine besylate | Norvasc® |

| Antiparkinsonian drugs | Benztropine Trihexyphenidyl HCL |

Cogentin® Artane® |

| Antipsychotics (butyrophenones and phenothiazines) |

Haloperidol Chlorpromazine Clozapine Quetiapine fumarate Risperidone Olanzapine |

Haldol® Thorazine® Clozaril® Seroquel XR® Risperdal® Zyprexa® |

| Antispasmodics | Oxybutynin | Ditropan® |

| Bronchodilators | Albuterol | Airet®; Proventil®; Rotocaps®; Ventolin®; Ventomax® |

| Diuretics | Furosemide Hydrochlorothiazide |

Lasix® Dyazide®; Maxzide® |

| Gastrointestinal drugs (gastric acid secretion inhibitor) | Lansoprazole | Prevacid® |

| Sedative – hypnotics | Zolpidem | Ambien® |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants | Cyclobenzaprine | Flexeril® |

Radiotherapy to head and neck

Another major cause of xerostomia is associated with fractionated radiation for treatment of malignant tumors of head and neck (Chambers et al., 2007). In the USA more than 50,000 individuals are annually diagnosed with head and neck cancers, which account for 3–5% of all cancers. A majority of these patients are older than 50 years of age (Jemal et al., 2010). Standard treatment is usually 5–7 weeks of radiotherapy for oral cancers with a dose of up to 70 Gy. This can have a profound and a long-lasting adverse effect on the function of salivary glands within the field of radiation. Loss of function is total dose, time, and gland dependent. Serous cells are more radiosensitive than mucous cells and parotid glands’ serous cells are more sensitive than the acinar cells in other glands. Patients receiving radiation begin to experience a significant decrease in salivary flow, increase in saliva viscosity, and xerostomia within the first week after initiation of therapy or when doses exceed 10 Gy. Doses exceeding 60 Gy cause permanent damage consisting of the loss of acinar cells, glandular fibrosis, and fatty degeneration of the gland parenchyma (Henriksson et al., 1994). The multiple symptoms resulting from salivary gland destruction and hyposalivation persist indefinitely, adversely affecting the patients’ quality of life.

Systemic disorders

Xerostomia in patients not taking any medications may be an indication of underlying systemic disease requiring further evaluation. The coexistence of multiple chronic diseases is very common among older adults. Many of these conditions adversely affect salivary gland function and are associated with hyposalivation.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is the most common autoimmune disease affecting exocrine glands predominantly in middle-aged women. The characteristic histopathologic features of affected salivary glands in SS include lymphocytic infiltration, sialadenitis, acinar atrophy, and ductal hyperplasia leading to the formation of epithelial foci called epimyoepithelial islands. These are irreversible and destructive changes of salivary and/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses