14

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

The overall incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is approximately 30% but can be as high as 80%. It is not only unpleasant and distressing for the patient, but also has important medical consequences:

- aspiration of gastric contents (especially in the recovery period following an anaesthetic when protective airway reflexes might not have fully returned);

- dehydration and electrolyte disturbance;

- increased intraocular and intracranial pressure in susceptible patients;

- delayed hospital discharge, and the need for day surgery patients to be admitted overnight;

- it is unpleasant and can lead to increased anxiety for subsequent operations.

Mechanism

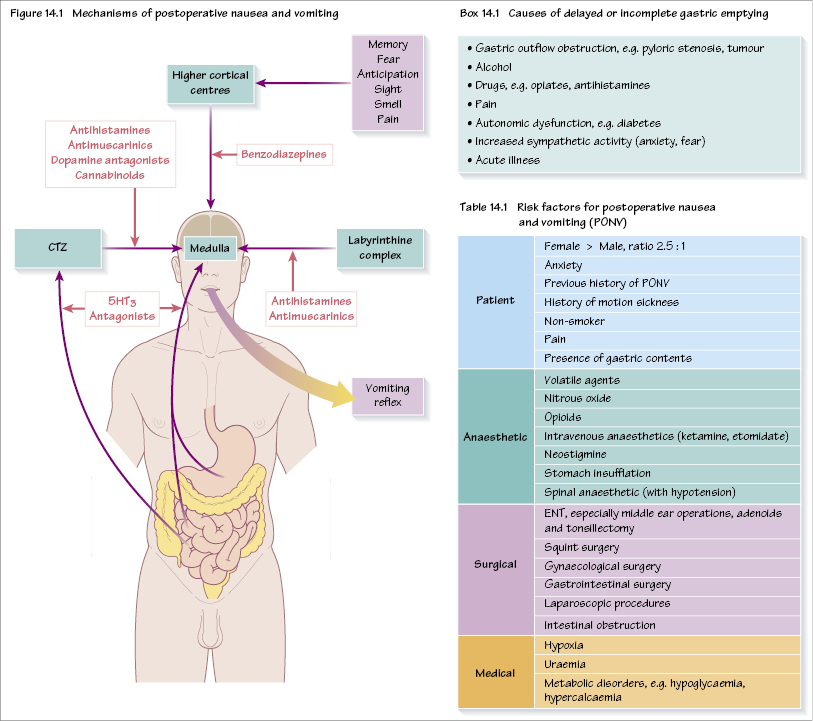

Afferent nerve fibres (mainly vagal) from the GI tract supply the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) which is situated in the area postrema in the caudal part of the floor of the 4th ventricle. There are both mechanoreceptors (detecting gut wall distension, e.g. in bowel obstruction) and chemoreceptors (detecting toxins etc.). Other afferents (e.g. higher cortical centres, vestibular apparatus) converge on the CTZ. The CTZ lies outside both the blood–brain barrier and the CSF–brain barrier, and so is able to detect stimulants to vomiting from both blood and CSF. The CTZ interacts with the vomiting centre (dorsolateral reticular formation of the medulla). Several receptors are involved: H1, ACh (M3), 5-HT3 and dopamine (D2) (Figure 14.1).

Treatment

Drug treatment

Most antiemetic drugs act on more than one receptor.

Antihistamines

e.g. cyclizine. These act on H1 central receptors (as opposed to H2 gastric receptors). Cyclizine also has an anticholinergic action and causes tachycardia when given intravenously.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses