Periodontics

Basic Features of the Periodontium

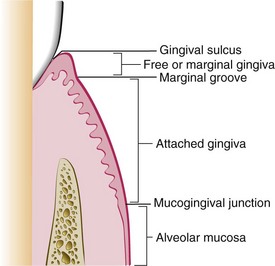

A The periodontium (Figure 14-1) is composed of gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone

FIGURE 14-1 Anatomy of the periodontium.

B The function of the periodontium is to attach the teeth to the alveolar bone tissues of the mandible and the maxilla

Gingiva

Definition

A Part of the oral masticatory mucosa that surrounds the cervical portion of the teeth and covers the alveolar process of the jaws

1. Marginal gingiva (unattached or free gingiva)

a. Unattached cuff-like tissue that surrounds teeth facially, lingually, and interproximally

(1) Gingival margin—most coronal portion; surrounds the teeth in a scalloped outline; located at or approximately 0.5 millimeters (mm) coronal to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ)

(2) Gingival groove—present in only 50% of gingival surfaces; when present, it is located 1 to 1.5 mm apical to the gingival margin at the base of the gingival sulcus

(3) Gingival sulcus—space formed by the tooth and the sulcular epithelium laterally and by the coronal end of the junctional epithelium (base of the sulcus) apically; in periodontal health, almost no gingival sulcus exists; a sulcular measurement of 1 to 2 mm facially and lingually and 1 to 3 mm interproximally is considered normal

(4) Interdental gingiva—occupies the interdental space coronal to the alveolar crest (clinically, it fills the embrasure space beneath the area of tooth contact)

(a) Interdental gingiva—consists of two interdental papillae (one facial and one lingual) that are connected by the concave interdental col

(b) Col is absent when teeth are not in contact

(c) Interdental gingiva, like facial and lingual gingivae, is attached to the tooth by the junctional epithelium and connective tissue fibers

a. Portion of the gingiva that is attached to the underlying periosteum of the alveolar bone and to the cementum by connective tissue fibers and the epithelial attachment

3. Changes in the width of attached gingiva result from changes at the coronal end

Histologic Features1,2

See the sections on “Oral histology,” “Oral mucosa,” and “Dento-gingival junction,” in Chapter 2.

1. Sulcular (crevicular) epithelium—stratified squamous, nonkeratinized epithelium that is continuous with the oral epithelium; lines the peripheral surface of the sulcus extending to the coronal border of the junctional epithelium

2. Junctional epithelium—part of the dento-gingival junction; stratified squamous, nonkeratinized epithelium that surrounds and attaches to the tooth on one side and attaches on the other side to the gingival connective tissue; new cells originate from the cells in the apical portion adjacent to the tooth and from the cells in contact with the connective tissue; epithelial cells are shed (desquamation) at the coronal end of the junctional epithelium, which forms the base of the gingival sulcus

a. The junctional epithelium is more permeable to cells and fluids than is the oral epithelium

b. The junctional epithelium serves as the route for the passage of fluid and cells from the connective tissue into the sulcus and for the passage of bacteria and bacterial products from the sulcus into the connective tissue

c. The junctional epithelium is easily penetrated by the periodontal probe; penetration is increased in inflamed gingiva

d. The length of the junctional epithelium ranges from 0.25 to 1.35 mm; most coronal portion of the anchoring periodontium in health

3. Epithelial attachment—basal lamina, hemidesmosomes, adhesion proteins (laminins), and anchoring fibrils that connect the junctional epithelium to the tooth surface at or slightly coronal to the CEJ

B Connective tissue (or lamina propria)—composed of gingival fibers (connective tissue fibers), intercellular ground substance, cells, and vessels and nerves (see Chapter 2, Figures 2-20 and 2-27)

1. Gingival fibers—composed of collagen fibers (60% of connective tissue volume) and an elastic fiber system composed of oxytalan, elaunin, and elastin fibers; fiber bundle groups provide support for marginal gingiva, including the interdental papilla (see also Chapter 2, Figure 2-28, B, and the section on “Oral histology, periodontal ligament for gingival fiber groups”)

2. Intercellular ground substance (or matrix)–similar to connective tissue in periodontal ligament

a. Fibroblasts (predominant cells)

(1) Produce various types of fibers found in connective tissue

(2) Instrumental in synthesis of intercellular ground substance

(3) Wound healing or healing after therapy is regulated by fibroblasts (see the section on “Regeneration and wound healing” in Chapter 7)

b. Other connective tissue cellular components—host defense cells

4. Vessels and nerves (see the section on “Blood supply to the periodontium”)

Normal Clinical Features

A Color—in light-skinned individuals, pale or coral pink; in dark-skinned individuals, coral pink to brown; color varies, depending on the degree of vascularity, amount of melanin, epithelial keratinization, and thickness of epithelium

1. Gingival margin—dull, smooth surface

2. Attached—stippled, “orange peel” surface present on facial surfaces; may not always be present in health

1. Gingival margin—firm and resilient; resists displacement

2. Attached gingiva—firmly bound to the underlying alveolar bone and cementum

1. Papillary contour—pointed; papilla fills proximal embrasure space to the contact point

2. Marginal contour—most coronal edge should form a knife-like edge with a scalloped configuration mesiodistally (follows the CEJ)

3. The contour varies with the shape and alignment of teeth and with the size and position of contacts

Periodontal Ligament

See the section on “Periodontal ligament” and Figure 2-27 in Chapter 2.

Functions

A Physical—attachment of the tooth to the bone, transmission of occlusal forces to the bone, absorption of the impact of occlusal forces, and maintenance of the proper relationship of gingival tissues to teeth

B Formative—participation in formation of cementum and bone and remodeling of the periodontal ligament by activities of connective tissue cells (cementoblasts, fibroblasts, osteoblasts)

C Resorptive—by the activity of connective tissue cells (primarily osteoclasts)

D Nutritive—nutrients carried through blood vessels to cementum, bone, and gingiva

E Sensory—proprioceptive and tactile sensitivity provided by innervation to the ligament

Clinical Considerations

A Thickness varies from 0.05 to 0.25 mm (mean, 0.2 mm), depending on the stage of eruption, the person’s age, and the function of a tooth; the ligament is thickest in the apical area and is thicker in functioning than in nonfunctioning teeth and in areas of tension than in areas of compression

B Periodontal ligament cells that form collagen in ligament bundles can also remodel the ligament through secretion of new collagen (fibroblasts) and resorption of older collagen (fibroclasts), as well as lateral resorption of adjacent bone (osteoclasts) when altered forces are applied (e.g., orthodontics)

C Accidentally exfoliated teeth can be reimplanted if handling of torn ligament is minimized before reimplantation

Cementum

See the section on “Cementum” in Chapter 2.

Clinical Considerations

A Compensates for occlusal wear and continuous eruption by apical deposition of cementum throughout life

B Protects the root surface from resorption during tooth movement

C Has a reparative function, which permits re-establishment of new connective tissue attachment after certain types of periodontal therapies

D When enamel and cementum do not meet, cervical hypersensitivity and caries are more likely

Alveolar Process

See the section on “Alveolar bone” and Figure 2-26 in Chapter 2.

Shape, Thickness, and Location

A The contour of the alveolar bone follows the contour of the CEJ and the arrangement of the dentition

B The shape of the alveolar crest is generally parallel to the CEJ of adjacent teeth; is approximately 1.5 to 2 mm apical to the CEJ

C Cortical plates generally are thicker in the mandible than in the maxilla

D Posterior areas—bone generally is thick, and cancellous bone separates the cortical plate from the alveolar bone proper

E Anterior areas—bone is thin, with little or no cancellous bone separating the cortical plate from the alveolar bone proper

F Dehiscence—situation in which the marginal alveolar bone is denuded, forming a defect extending apical to the normal level, exposing an abnormal amount of root surface

G Fenestration—situation in which the margin of alveolar bone is intact; an isolated lack of alveolar bone on the root surface leaves it covered only by the periosteum and overlying gingiva

Radiographic Features of the Normal Periodontium

A Alveolar crest—thin, radiopaque line continuous with the lamina dura; the shape is dependent on the following:

B Interdental septum—proximal alveolar bone bordered by the alveolar crest

C Lamina dura—radiographic image of the alveolar bone proper; may or may not be present as a thin radiopaque line surrounding the bone adjacent to the periodontal ligament

D Periodontal ligament space—thin radiolucent line surrounding each tooth between the root and adjacent alveolar bone

E Supporting bone—radiopacity of the trabecular pattern varies, depending on the amount, pattern, and presence of cancellous and cortical bone

F Limitations of radiographs—radiographs:

1. Do not show the relationships between soft and hard tissues

2. Do not show the initial signs of early bone loss

3. May not accurately show interproximal bony changes

4. Do not show bone changes on facial or lingual surfaces; these bony plates are obscured by teeth roots

5. Do not reveal current cellular activity; only reflect past events

6. Have their diagnostic value affected by variations in technique

Blood Supply, Lymph, and Innervation of the Periodontium1,2

See the section on “Blood and lymph” and “Nerve tissue” in Chapter 2.

A Blood supply originates from the inferior and superior alveolar arteries

B Lymph drains into larger lymph nodes and veins

C The nerve supply is derived from the branches of the trigeminal nerve and thus is sensory in nature; nerve branches terminate in the periodontal ligament, on the surface of alveolar bone, and within gingival connective tissue; receives stimuli for pain (nociceptors) and for position and pressure (mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors)

Diseases of the Periodontium

Classification of Periodontal Diseases1–3

See the section on “Periodontal diseases” in Chapter 9.

A Importance of disease classification

1. Useful for dental hygiene diagnosis, prognosis, care plans, and legal documentation

2. Classifications of periodontal diseases are changing as new information about causes, pathogenicity, and host factors continues to evolve

B Current classifications of periodontal diseases3

a. Dental plaque–induced gingival diseases—can occur on a periodontium with no attachment loss that is not progressing; include plaque-associated gingivitis and gingival diseases modified by systemic factors such as disorders of the endocrine system (hormonal), blood dyscrasias, medications, and malnutrition

b. Non–plaque-induced gingival lesions—include gingival diseases of specific bacterial, viral, fungal, or genetic origin; gingival manifestations of systemic conditions such as mucocutaneous disorders and allergic reactions; and traumatic lesions, foreign body reactions, and otherwise nonspecified gingival lesions

2. Chronic periodontitis—localized or generalized

3. Aggressive periodontitis—localized or generalized

4. Periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic diseases (i.e., hematologic or genetic)

5. Necrotizing periodontal diseases

6. Abscesses of the periodontium

Gingival Diseases1,3

1. Signs and symptoms confined to the gingiva

2. Presence of bacterial plaque, which initiates or exacerbates the lesion

3. Clinical signs of inflammation

4. No loss of attachment or stable attachment levels; possible precursor to attachment loss

B Dental plaque–induced gingivitis

1. Inflammation of the gingiva resulting from bacterial plaque biofilm at the gingival margin

2. Most common form of periodontal disease; prevalent in all age groups

3. Change in gingival color and contour (redness, swelling, enlargement); increased sulcular temperature and gingival exudate; bleeding on provocation; reversible with plaque removal

4. Sensitivity or tenderness can occur, although not necessarily present in all clients

5. Absence of attachment loss and bone loss is characteristic; after active periodontal treatment and resolution of inflammation in periodontitis, tissue becomes healthy, but attachment loss remains; dental plaque–induced gingivitis on a reduced periodontium can occur in these cases if gingival inflammation arises without evidence of progressive attachment loss

C Gingival diseases associated with endocrine changes or endogenous sex hormones

1. Periodontal tissues are modulated by androgens, estrogens, and progestin

2. Most information exists about sex hormone–induced effects in women: menstruation, pregnancy, and puberty

3. Gingival response requires bacterial plaque in conjunction with steroid hormones

a. Puberty-associated gingivitis—occurs in adolescents during puberty in both genders when the dramatic rise in hormone levels has a transient effect on gingival inflammation; signs of gingivitis exist in the presence of relatively sparse deposits

b. Menstrual cycle–associated gingivitis—significant and observable inflammatory changes occur most frequently during ovulation

c. Pregnancy-associated gingivitis—some of the most remarkable endocrine changes occur during pregnancy owing to increased plasma hormone levels; features are similar to plaque-induced gingivitis, but relatively little bacterial plaque may be present

d. Pregnancy-associated pyogenic granuloma (pregnancy tumor)—pronounced response of gingiva to bacterial plaque at gingival margin in the form of a sessile or pedunculated protuberant mass; more common interproximally; regresses after parturition

D Gingival diseases associated with medications (drug-influenced gingival diseases)2–4

1. Drug-influenced gingival enlargement—overgrowth of the gingiva most commonly associated with the following:

a. Anticonvulsant agents (e.g., phenytoin)—occurs in about 50% of users

b. Immunosuppressant agents (e.g., cyclosporin A)—occurs in about 30% of users

c. Calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine, verapamil, diltiazem, sodium valproate)—occurs in 6% to 20% of users

2. Occurs most frequently in the anterior gingiva, especially in children; onset within 3 months of drug regimen

3. Changes in gingival contour, size, and color all because of enlargement; increased gingival exudate and bleeding on provocation can coexist; first occurs interproximally

4. Found in the gingiva, with or without bone loss; not associated with attachment loss

5. Plaque control can limit the severity of the pronounced inflammatory response of the gingiva

6. Oral contraceptive–associated gingivitis—also can occur in the presence of marginal plaque because of the pronounced inflammatory response of the gingiva in women using certain oral contraceptive agents; inflammation and enlargement are reversible when the drug is discontinued

E Gingival diseases associated with systemic diseases

1. Diabetes mellitus–associated gingivitis—found in children with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus

2. Leukemia-associated gingivitis (hematologic gingival disease)—primarily found in persons with acute leukemia

3. Both diseases manifest with pronounced inflammatory response to bacterial plaque; changes in gingival color and contour; increased bleeding on provocation

F Gingival diseases associated with malnutrition

1. Malnutrition leads to compromised host response and defense mechanisms

2. Increased susceptibility to infection may exacerbate gingival response to bacterial plaque

3. Scurvy can also result from ascorbic acid (vitamin C) deficiency; the resultant gingival lesions are described as erythematous, bulbous, hemorrhagic, swollen, and spongy

G Non–plaque-induced gingival lesions3

1. Infectious gingivitis—includes specific bacteria (e.g., Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Treponema pallidum, streptococci), viruses (e.g., herpes simplex types 1 and 2, varicella zoster, and papillomavirus), fungi (e.g., Candida species), or genetic conditions (e.g., hereditary gingival fibromatosis) (see the section on “Periodontal diseases” in Chapter 9); linear gingival erythema occurs in individuals who have acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or other immunocompromising diseases

a. Clinical changes—distinct band of severe erythema on marginal gingiva; can be localized or generalized; sometimes punctuated red dots are also present on attached gingiva; no ulceration or loss of attachment occurs

b. Radiographic changes—none; normal findings

c. Cause—immunosuppressed host response to bacterial plaque

d. Treatment—scaling and debridement with povidone–iodine irrigation for antimicrobial and topical anesthetic effect; prescription of antifungal agents if candidiasis is also present; critical importance of thorough self-care practices, including mechanical removal of bacterial plaque and twice-daily 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses, 1-month re-evaluation, and continued care, must be stressed to the client

2. Dermatologic diseases, including lichen planus, pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, erythema multiforme, psoriasis, and lupus erythematosus, also may present with gingival manifestations; the diagnosis depends on clinical findings and biopsy specimens (see the sections on “Major aphthous ulcers,” “Skin diseases,” and “White lesions” in Chapter 8)

3. Allergic reactions in the oral mucosa are uncommon but can be caused by dental restorations, dentifrices, mouthwashes, and food allergens; signs and symptoms do not resolve when oral hygiene is instituted

4. Foreign body reactions occur when ulceration of the gingival epithelium allows entry of a substance into the gingival connective tissue; most commonly is an amalgam tattoo

5. Mechanical trauma can be accidental, iatrogenic, or factitious; results in gingival or tooth abrasion, recession, ulceration, inflammation, or laceration

Chronic Periodontitis2,3

A Slowly progressive; most common in adults; can also occur in children and adolescents

B The disease results from the inflammatory process originating in the gingiva (gingivitis) and extending into the supporting periodontal structures; may have periods of activity and remission; has slow to moderate progression; may have periods of rapid progression

1. Can be further classified on the basis of extent and severity

a. Extent—number of sites involved

b. Severity—clinical attachment loss (CAL)

(1) Early—progression of gingival inflammation into the deeper periodontal structures and alveolar bone crest, with slight bone loss; with normal gingival contour, usual periodontal probing depth is 2 to 3 mm, with slight loss of connective tissue attachment and alveolar bone; average 1 to 2 mm attachment loss

(2) Moderate—a more advanced state of the above condition, with increased destruction of periodontal structures and noticeable loss of bone support, possibly accompanied by an increase in tooth mobility; average probing depth of 4 to 5 mm, with normal gingival contour; average 3 to 4 mm attachment loss

(3) Advanced—further progression of periodontitis, with major loss of alveolar bone support >30%;5 usually accompanied by increased tooth mobility; furcation involvement in multiple-rooted teeth is likely; recession is common; average probing depth 6 mm or more, with normal gingival contour; average ≥5 mm attachment loss

2. Radiographic features (see the section on “Changes in the periodontium associated with disease”)

3. Cause—host response to bacterial plaque biofilm; the amount of destruction is consistent with the presence of local factors; subgingival calculus is frequently seen; is associated with various microbial patterns; can be associated with local predisposing factors; may be modified by systemic diseases and other risk factors

4. Treatment—nonsurgical or surgical periodontal therapy, or both, depending on extent and severity, followed by periodontal maintenance procedures

C Chronic periodontitis can be recurrent and refractory (nonresponsive); not all cases of periodontitis have successful treatment outcomes

Aggressive Periodontitis1–3,6

A Can occur at any age; may be localized or generalized

1. Occurs in persons otherwise healthy

2. Rapid attachment loss and bone loss, which may or may not be self-arresting

4. Secondary features that are less universal include the following:

a. Bacterial plaque inconsistent with the severity of periodontal destruction

b. Elevated proportions of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and sometimes Porphyromonas gingivalis

c. Phagocyte abnormalities and poor antibody response

d. Progression of attachment loss and bone loss can be self-arresting

C Localized aggressive periodontitis

1. Circumpubertal onset most common

2. Localized incisor and first-molar onset with interproximal attachment loss on at least two teeth (one first molar) and involving no more than two teeth other than incisors and first molars

D Generalized aggressive periodontitis

1. Most common before age 30, but may also occur in older persons

2. Pronounced episodic nature of bone loss and attachment loss

3. Generalized interproximal attachment loss affecting at least three permanent teeth other than incisors and first molars

E Treatment—same as for chronic periodontitis; systemic antibiotic (tetracycline derivative or metronidazole and amoxicillin therapy) and diligent periodontal maintenance procedures

Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Diseases2,3

A Systemic factors modify all forms of periodontal disease, but some systemic diseases cause periodontitis; the listing is categorized under broad headings; other diseases may be added to the list in the future

B Hematologic disorders—see the section on “Blood dyscrasias” in Chapter 8

1. Neutrophil deficiencies cause severe destruction of periodontal tissues; leukocyte activities such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and killing or neutralization of ingested organisms or substances must be integrated for adequate protection

2. Quantitative leukocyte disorders

a. Neutropenia—the malignant form involves necrosis and ulceration of marginal gingiva and bleeding; more cyclic or chronic forms involve deep periodontal pockets with extensive, generalized bone loss

b. Leukemia—most common in the acute form; symptoms include generalized gingival enlargement, swelling caused by cellular infiltrate, and bleeding related to associated thrombocytopenia

C Genetic disorders1,6 (see the section on “Genetics” in Chapter 7)

1. Genetic disorders usually manifest early in life and have similar signs and symptoms as those of aggressive forms of periodontitis; host genetic factors are believed to be important determinants in a person’s susceptibility to periodontitis

2. Disorders associated with periodontitis include familial and cyclic neutropenia, Down syndrome, leukocytic deficiency syndrome, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, histiocytosis syndrome, glycogen storage disease, infantile genetic agranulocytosis, Cohen syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (types IV and VIII), and hypophosphatasia; rare conditions such as Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome have the strongest evidence linking genetic mutations with periodontitis6

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses