Periodontal Surgery

Peter M. Loomer and Dorothy A. Perry

• Describe the rationale for periodontal surgical treatment.

• Recognize the clinical conditions that are most likely to benefit from periodontal surgery.

• Define the types of periodontal surgery:

Excisional periodontal surgery

Excisional periodontal surgery

Incisional periodontal surgery

Incisional periodontal surgery

• Describe the healing of tissues after periodontal surgery.

• Define postoperative procedures.

• Describe postoperative instructions for patients receiving periodontal surgery.

• Define the changes and modifications in plaque biofilm control required for patients after periodontal surgery.

• Identify the role of the dental hygienist in the surgical treatment of periodontal disease.

Rationale for Periodontal Surgery

Periodontal educators have identified a number of goals for periodontal surgery.1 These goals are defined in Box 14-1. All these goals are valid reasons for recommending periodontal surgery.

Advantages Of Periodontal Surgery

The major benefit and indication for periodontal surgery as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal treatment is to gain access to the root surface for scaling and root planing. It also improves access for plaque biofilm control. Periodontal surgery results in better access to furcations, complex root surfaces, and infrabony pockets (those apical to the crest of bone, surrounded by bone on one or more sides), areas that are the most difficult to treat by scaling and root planing. Improving access for plaque biofilm control by the patient may require removing tissues or bony forms that block the patient from adequately removing as much biofilm as necessary to control the disease. Other advantages of periodontal surgery include improved access to periodontal abscesses to obtain drainage and the ability to expose root surfaces for restorative dentistry. In addition, numerous new techniques are being used to improve patient aesthetics by altering the position of the gingival margin.2

Disadvantages and Contraindications Of Periodontal Surgery

There are a number of disadvantages and contraindications to periodontal surgery. These include the health status or age of the patient and the specific limitations of each procedure.2 From the patient’s perspective, the disadvantages of surgery are usually limited to time, cost, aesthetics, and discomfort.

General Considerations for Periodontal Surgery

Probing Pocket Depth

A periodontal pocket is a deepened gingival sulcus with an infected root surface covered by an ulcerated epithelial surface, with underlying inflamed connective tissue. The pocket is bound coronally by the gingival margin on one side by the root surface, on the other side by the epithelial surface, and at the base by the junctional epithelium. Studies have shown that scaling and root planing is effective in controlling periodontal disease to probing depths of about 4 mm.4 Pockets deeper than 5 mm are difficult to instrument and therefore often remain infected, even after the best dental hygiene care. Pockets with probing depths greater than 9 mm suggest extreme loss of attachment, which makes the long-term prognosis for retaining the affected teeth poor.

Probing pocket depth is not always equal to clinical attachment loss. The probing depth is the measurement from the crest of the gingival margin to the base of the pocket. The deeper the probing depth, the more difficult is the complete removal of calculus. Therefore, the indication for periodontal surgery is stronger. Attachment loss, rather than probing depth, is measured from the cementoenamel junction to the base of the pocket. If the gingival margin is on the root surface, as when there has been recession, the attachment loss is greater than the probing depth. If the gingival margin is on the enamel surface of the crown, as in gingival hypertrophy, then the attachment loss is less than the probing depth. Attachment loss represents bone destruction, which in turn affects the long-term prognosis of the tooth. The concepts of probing depth and clinical attachment loss are discussed in Chapter 8.

Although surgery may be needed to treat pockets deeper than 5 mm, not all pockets of this depth require surgery. The 5-mm guideline is only the first step in identifying patients who may be helped by periodontal surgery. Patients with moderate pocket depths of 5 to 6 mm may be monitored with a wait-and-see approach to determine whether nonsurgical periodontal therapy and careful maintenance are adequate. If there is no progression of the periodontal disease in these cases, then periodontal surgery is not necessary. However, it is not always safe to wait and see. If the periodontal disease progresses and more attachment loss results, the prognosis for a tooth may worsen. Also, probing measurements are inexact. Measurements may differ by as much as 1 mm because of variations in probing technique. Therefore, to know that the disease is definitely progressing, a 2-mm increase in probing depth (and thus bone loss) must be observed over time. If surgery is postponed, the dentist (and patient) must be willing to risk this 2-mm bone loss.5

Bone Loss

The base of the periodontal pocket is not at the level of the crest of the alveolar bone. There is usually 1 to 2 mm of connective tissue attachment covered by epithelium between the probing depth and the alveolar bone. This area is termed the biologic width6 and must be considered when estimating the amount of attachment remaining on a periodontally involved tooth.

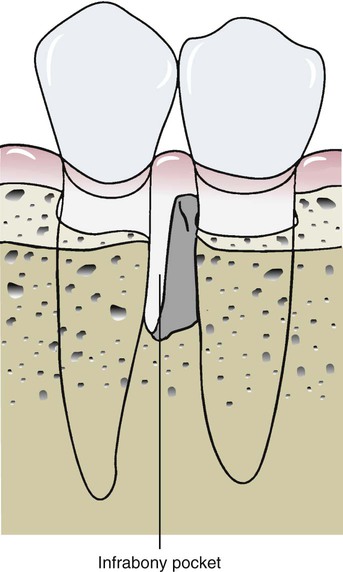

Bone loss caused by periodontal disease results in osseous defects. These may occur in either a horizontal dimension, where the bone resorbs equally on the mesial and distal surfaces of the teeth, as seen in Figure 14-1, or a vertical dimension, where the resorption is unequal around the teeth, as illustrated in Figure 14-2. Pockets that are coronal to horizontal bone loss are often called suprabony pockets, whereas those that extend apically beyond the crest of the bone are called infrabony pockets.

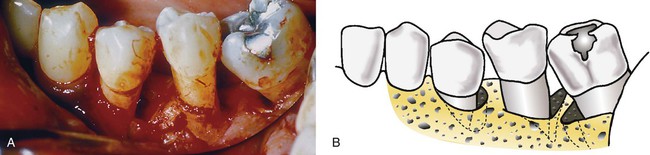

Obvious furcation involvement of the first molar and cervical caries is seen at the mesial and distal cementoenamel junction of the first molar. (Courtesy of University of California, San Francisco, Division of Periodontology.)

Although there has been some horizontal bone loss on the adjacent teeth, the bone level is greatly reduced on the premolar, resulting in infrabony pockets.

Vertical bone loss may also occur in a variety of configurations that are usually described by the number of bony walls remaining. When all the walls of the osseous defect are within the bone housing, they may be termed intrabony pockets. These types of bony defects are shown in Figure 14-3.

A, A two-wall defect on the distal aspect of the first premolar, a one-wall defect on the distal aspect of the second premolar, and a three-wall defect on the mesial aspect of the first molar are evident in this photograph. B, The diagram shows the remaining walls of bone around the periodontal pockets. The two-wall defect on the first premolar shows bone destroyed on the distal root surface and the buccal alveolar process; therefore, two bony walls remain. The one-wall defect on the second premolar shows bone destroyed on the distal root surface and on both the buccal and the lingual alveolar processes; therefore, one wall remains. The three-wall defect on the mesial aspect of the molar shows bone destroyed on the root surface, but the alveolar process remains; therefore, three walls of bone remain surrounding the pocket.

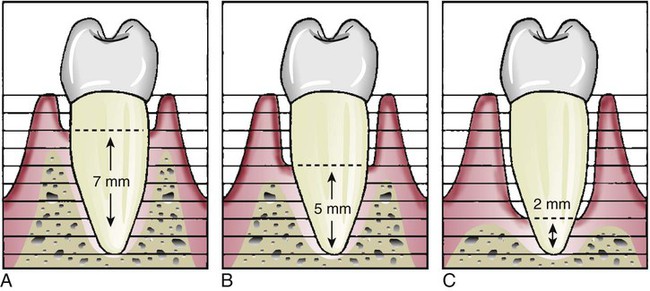

The amount of bone remaining around a tooth is an important consideration in the decision to perform periodontal surgery. Large amounts of bone supporting a tooth may allow the clinician to take a wait-and-see approach to postpone or avoid periodontal surgery. However, if the amount of bone is already reduced, delaying periodontal surgery may radically decrease the prognosis for the tooth. This rationale is illustrated in Figure 14-4.

A, When some bone loss is present, it may be safe to postpone surgery and take a wait-and-see approach; an additional bone loss of 2 mm may not alter the prognosis of the tooth. B, When half of the bone has been lost, an additional 2-mm loss can seriously jeopardize the tooth; therefore, surgery is highly recommended. C, With advanced bone loss, surgery may be performed in an effort to save the tooth, but the prognosis is poor.

Periodontal surgery that includes modification of the bone level or shape is called osseous surgery. The amount of bone remaining is important in determining whether periodontal surgery will be beneficial. If too much bone has been lost through disease or so much bone must be removed during surgery that the tooth will be weakened, osseous surgery becomes a less attractive option for treatment. Other procedures, such as grafting or regeneration techniques, may be required. Generally, osseous surgery performed to correct irregularly shaped defects of the bony support around the tooth is indicated when at least half of the bone support remains, as shown in Figure 14-5.

The shaded portion shows bone that would need to be removed during surgery to eliminate the bony defect. However, this bone removal would substantially weaken the adjacent tooth, which is a consideration in planning the surgery and can be a contraindication for osseous recontouring.

Personal Plaque Biofilm Control Of The Patient

The progression of periodontal disease may increase after periodontal surgery if plaque biofilm is not adequately controlled.7 Therefore, every patient should establish the best possible supragingival plaque biofilm control before surgical therapy is initiated. If plaque biofilm control is poor, surgical intervention should be postponed or abandoned because it will not prevent the recurrence of periodontal infection and the possible loss of teeth.

Types of Periodontal Surgery

Many methods of classifying periodontal surgery have been described. One approach is to name the procedure for the clinician who first described it—for example, the Widman flap. Another approach is to describe how the procedure is performed, as with gingivectomy, which means to remove the gingiva. Lang and Löe proposed a convenient classification of periodontal surgical procedures into five basic categories8:

• Procedures for pocket reduction or elimination

• Procedures for access to root surfaces

• Procedures for treatment of osseous defects

Procedures For Pocket Reduction Or Elimination

Excisional Periodontal Surgery

Procedure.

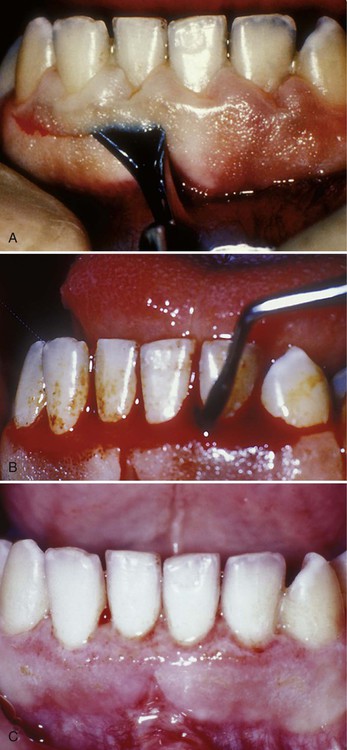

During gingivectomy, the surgeon marks the bottom of the pockets with a periodontal probe or forceps. The gingiva is excised with knives at a 45-degree angle to the gingival surface, keeping the incision within the keratinized gingiva. This practice results in a thin tissue margin at the dentogingival junction. After removal of the majority of the gingival tissues, the underlying exposed connective tissue is refined and trimmed with knives, burs, or other instruments. Exposed root surfaces are carefully examined for residual calculus and roughness and they are cleaned and smoothed as necessary with curettes. Bleeding after surgery is controlled with gauze pads dampened with saline solution, and the surgical area is packed with a periodontal dressing to reduce postoperative discomfort and protect the sensitive underlying connective tissue. Healing is usually uneventful and the gingival epithelium is reestablished 2 weeks after surgery.9 An example of a gingivectomy procedure is presented in Figure 14-6.

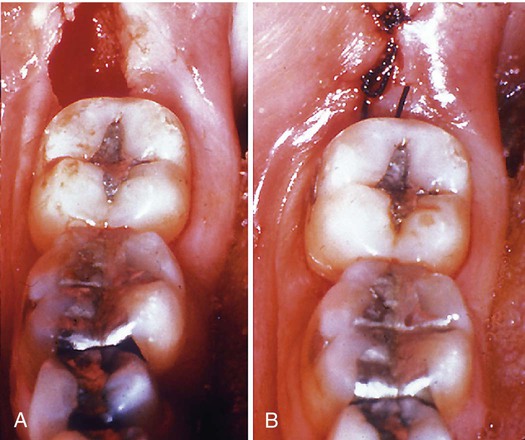

A, The gingivectomy incision is through the keratinized tissue to the root surfaces of the teeth. B, The exposed connective tissue is trimmed with a periodontal knife to smooth and shape it to a physiologic form. C, Healing of the gingivectomy wound after 1 week. The tissue is reepithelialized by growing in from the margins of the wound.

Contraindications.

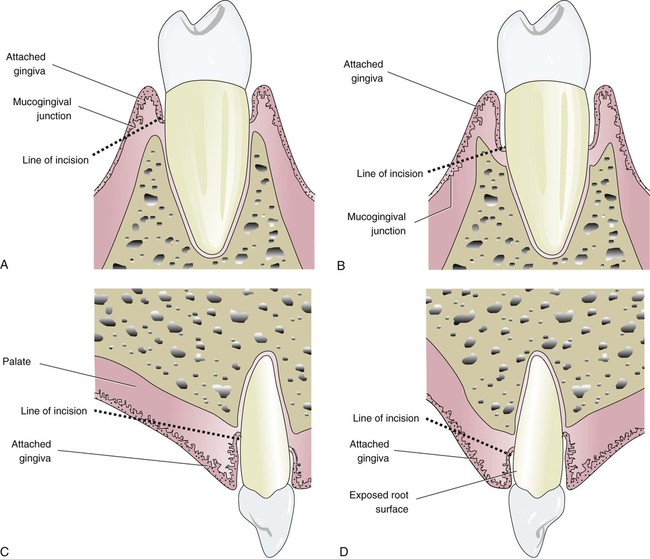

There are many contraindications to excisional surgery, which is why it is rarely used for periodontal pocket reduction. Concerns about this procedure, which are illustrated in Figure 14-7, include the following:

Excisional surgery is not the treatment of choice under the following circumstances. A, The incision cannot be made entirely through the keratinized gingiva. B, Infrabony pockets interfere with the correct line of incision. C, The incision would leave a wide wound—for example, on a palatal surface. D, Removal of the gingiva could expose long root surfaces that may be unsightly to the patient, sensitive to cold, and susceptible to root caries.

• The primary contraindication is that the procedure does not permit access to infrabony pockets, those below the crest of the alveolar bone, a highly common occurrence in periodontitis.

• A wide wound is created, so healing is relatively slow while the epithelium grows in from the edges of the wound, and there is significant postoperative discomfort.

• The anatomy of the surrounding area may prevent incising the tissues at the proper angle or minimal width of attached gingiva may prevent keeping the incision within the keratinized tissue.

• The procedure exposes the root surfaces of the teeth, often resulting in unacceptable aesthetics, sensitivity to heat and cold, and susceptibility to root caries.

Incisional Periodontal Surgery

Incisional surgery, commonly called periodontal flap surgery or simply flap surgery, is the procedure of choice when excisional periodontal surgery cannot be performed for pocket reduction. This procedure is called flap surgery because the tissues are pushed away from the underlying tooth roots and alveolar bone, much like the flap of an envelope. Flap surgery includes a variety of techniques for pocket depth reduction. Depending on the clinical circumstances and the preference of the surgeon, the alveolar bone may be resected or modified during the surgical procedure. The usual incisional technique for pocket reduction with flap surgery is called the apically positioned flap because the flap is sutured at a more apical location on the tooth roots to reduce pocket depth.9

Procedure.

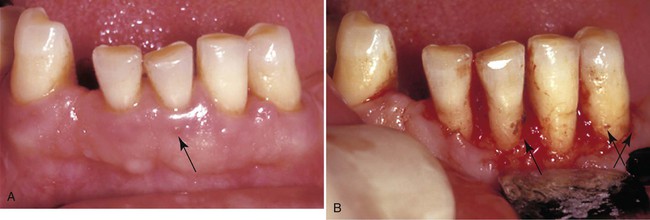

After anesthesia is given, pockets are probed to determine their depths and the bony contours are “sounded” by pushing the periodontal probe through the tissues until the crest of the alveolar bone is detected. The surgeon uses this information to design the incision around the necks of the teeth to retain as much tissue as possible while allowing for pocket reduction. In thick tissues, this incision may be several millimeters away from the root surfaces. Flaps of gingiva are created that are pushed away from the alveolar bone and teeth, usually on the buccal and lingual surfaces, with a periosteal elevator. In this way, the infected epithelium, connective tissue, and granulation tissues can be removed with curettes, scalers, and ultrasonic instruments. The roots are examined for residual calculus and cleaned and smoothed as necessary. The flaps are then readapted at a more apical level to reduce the pockets. At this stage, the surgeon may reduce the bony ledges or may further elevate the flaps past the mucogingival junction to position it for proper adaptation. The surgical wound is closed by suturing the flaps together in the interproximal papillae and closely adapting them around the root surfaces. A periodontal dressing may be applied to help adapt the gingiva to the alveolar bone and assist with pocket reduction by applying pressure to the healing flap. This procedure is illustrated in Figure 14-8.

The access flap permits thorough cleaning of root surfaces. In this case, nonsurgical therapy did not result in pocket reduction and adequate healing of the gingival tissues. A, Presurgical appearance. Note the reddened and inflamed tissue around the anterior teeth, particularly the swelling on the facial surface of the incisor (arrow). B, When the flap is reflected, significant calculus remains on all the root surfaces (arrows). (Courtesy of Dr. Gary C. Armitage, University of California, San Francisco, School of Dentistry, Division of Periodontology.)

Contraindications.

Special modifications of pocket reduction surgery include combinations of incisional and excisional techniques, such as distal wedge surgery and internal beveled gingivectomy. These techniques are indicated in specific areas, such as the palatal tuberosity region, or where tissues are thick and not easily managed by one method alone.9 The distal wedge procedure is shown in Figure 14-9. It permits adequate plaque control on the distal surface of the last tooth in the mandibular arch.

Procedures for Gaining Access To The Root Surface

The goal of access flap procedures is to provide access to the root surfaces for debridement and to create conditions for reattachment of the gingival tissues to the root. These access procedures include the modified Widman flap,9,10 the excisional new attachment procedure,11 and open flap curettage.12 Most of these procedures are similar and differ only in the details of the technique. The modified Widman flap, for example, uses three incisions to separate the pocket lining from the tooth in a controlled manner, whereas the excisional new attachment procedure usually does not involve elevating the flap past the mucogingival junction. The goal of all these procedures is the same—to gain access to the root surface for plaque biofilm and calculus removal, including scaling and root planing. Pocket reduction by apical positioning is not the goal of access flap procedures.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses