Tumors of Orofacial Region

Focal Epithelial Hyperplasia/Heck’s Disease

Keratoacanthoma/Self-healing Carcinoma

Benign Chondroblastoma (Codman’s Tumor)

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

Fibrous Hyperplasia: Denture-related

Odontogenic Tumors

Odontogenic tumors are lesions of great interest and importance to oral physicians, pathologists and maxillofacial surgeons alike, who for several decades have studied and catalogued these lesions and developed modalities for adequate treatment.

Benign Odontogenic Tumors

Theories of Tumor Development

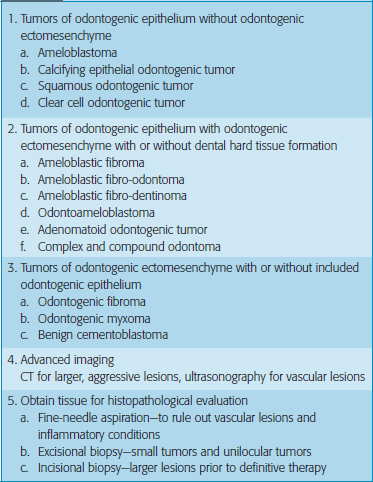

Classification

With the first edition of the WHO classification on tumors, about 30 years ago, the terminology and the diagnostic framework became available, and this modern and logically constructed classification greatly intensified research into the subject, and markedly stimulated the urge to publish new findings. In 2000, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in Lyon, France started a new book series, WHO Classification of Tumors. The new WHO Blue Books encompass both histopathological and genetic criteria for tumor classification (Table 1). Clinically it also can be classified based on site, age and gender predilection as given in Tables 2–4.

Table 2

Tumors based on the age of predilection

| 0–25 years | More than 40 years |

| Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor | Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor |

| Ameloblastic fibroma | |

| Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma | Ameloblastoma |

| Odontoma | Squamous odontogenic tumor |

| Peripheral ossifying fibroma | Odontogenic myxoma |

| Benign cementoblastoma | Calcifying odontogenic fibroma |

| Ameloblastic odontoma |

Table 4

Tumors based on the site of predilection

| Maxilla | Mandible |

| Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor | Ameloblastoma |

| Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor | Ameloblastic odontoma |

| Odontoma | |

| Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma | Benign cementoblastoma |

| Squamous odontogenic tumor | Odontogenic myxoma |

| Calcifying odontogenic fibroma |

Diagnosis of benign tumors

Complete history: Pain, loose teeth, occlusion, swellings, dysesthesia, delayed tooth eruption

Complete history: Pain, loose teeth, occlusion, swellings, dysesthesia, delayed tooth eruption

Thorough physical examination: Inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation

Thorough physical examination: Inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation

Plain radiographs: Panaromic radiographs and dental radiographs at contrasting angles

Plain radiographs: Panaromic radiographs and dental radiographs at contrasting angles

Ameloblastoma

Classification

Table 3

Tumors based on the gender of predilection

| Male | Female |

| Ameloblastoma | Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor |

| Ameloblastic fibroma | |

| Ameloblastic fibro-odontoma | Squamous odontogenic tumor |

| Ameloblastic odontoma | |

| Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor | Odontogenic myxoma |

| Odontoma | Calcifying odontogenic fibroma |

| Benign cementoblastoma |

Clinical features

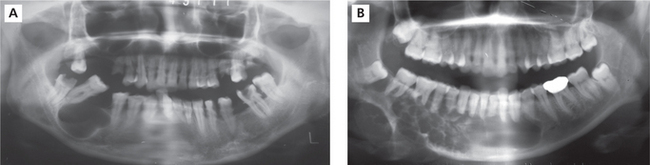

The tumor is slow growing and in the early stages may be asymptomatic and discovered as an incidental finding. As the tumor enlarges the patient may become aware of a gradually increasing facial deformity and expansion of the jaw bone (Figure 1A, B). The enlargement is usually bony hard, non-tender, and ovoid or fusiform in outline but in advanced cases, egg-shell crackling may be elicited due to thinning of the overlying bone. However, perforation of bone and extension of the tumor into soft tissues are late features. In the maxilla, even large tumors may produce little expansion as the lesion can extend into the sinus and beyond. Teeth in the area of the tumor may become loosened, but pain is seldom a feature.

Figure 1 A.B (A)Ameloblastoma involving mandible.(B)Intraoral view of ameloblastoma involving mandible. Courtesy: Dr Foluso Owotade

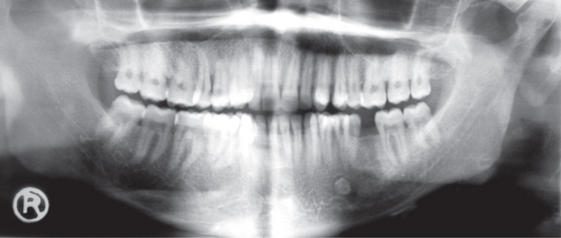

Radiographically, the ameloblastoma appears most commonly as a multiloculated radiolucency (Figure 2A, B). Roots of teeth involved by the tumor show varying degrees of resorption. As the tumor enlarges it may become associated with an unerupted tooth, particularly an impacted third molar, and the appearances may mimic those of a dentigerous cyst. Less frequently, ameloblastomas present as a single unilocular radiolucency indistinguishable from an odontogenic cyst.

Histopathology

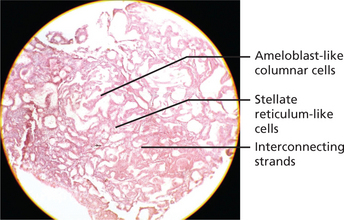

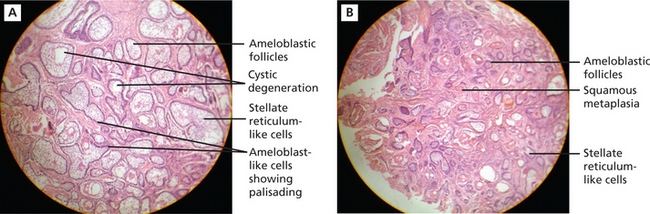

There are six histologic subtypes: follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, granular cells, basal cell and desmoplastic. These can be found combined or isolated and not related to prognosis of the tumor. The two main patterns are anastomosing epithelial strands and fields or discrete epithelial islands. The former pattern is called the plexiform (Figure 3) type, the others the follicular (Figure 4A). Both may occur within the same lesion. The follicles consist of a central mass of loosely connected, angular cells resembling the stellate reticulum of the normal enamel organ, surrounded by a layer of cuboidal or columnar cells resembling ameloblasts. The nuclei of the latter are situated away from the basal ends of the cells, and this is described as reversed polarity. The follicles are separated by varying amounts of fibrous connective tissue stroma. A variety of changes can occur within the stellate area of the follicles and these include cystic breakdown, squamous metaplasia, and granular cell change. The tumor epithelium in the plexiform type is arranged as a tangled network of anastomosing strands and irregular masses, each of which shows the same cell layers as for the follicular pattern. Thus, each strand or mass is bounded by columnar or cuboidal cells resembling ameloblasts, while the central area is occupied by stellate reticulum-like cells. Microcyst formation is commonly seen.

Figure 3 Histopathological picture showing plexiform ameloblastoma. Courtesy: Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, MCODS, Mangalore

Figure 4 A.B (A) Histopathological picture showing follicular ameloblastoma. (B) Acanthomatous ameloblastoma. Courtesy: Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, MCODS, Mangalore

When extensive squamous metaplasia, often associated with keratin formation, occurs in the central portion of a follicular ameloblastoma, the term ‘acanthomaotus ameloblastoma’ is used (Figure 4B).

Literature review

Ameloblastoma is a tumor with a complex biological character and presents a high recurrence rate even in patients treated with radical therapy. It has been reported that the aggressiveness of ameloblastoma may be related to the histological subtype, in fact.

Clear-Cell Odontogenic Tumor (Carcinoma)

Microscopically, nests and cords of clear cells are seen. Some peripheral palisading may be present.

Calcifying Epithelial Odontogenic Tumor

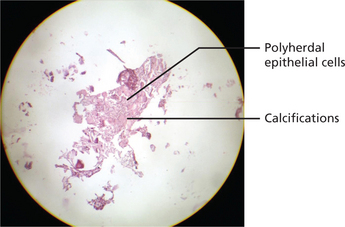

Histopathology

The calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor consists of sheets of polygonal cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm, distinct cell borders, and very conspicuous intercellular bridges. Nuclei are pleomorphic with prominent nucleoli; cells with giant nuclei and multiple nuclei are also present. The epithelial tumor islands as well as the surrounding stroma frequently contain concentrically lamellated calcifications. Stromal deposits of bone and cementum may occur (Figure 5).

Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor

Clinical features

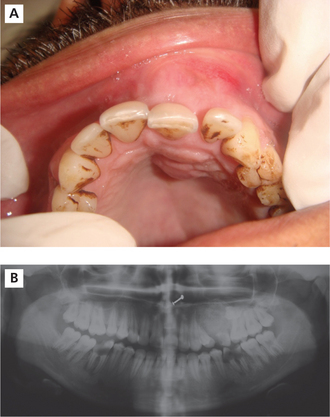

The adenomatoid odontogenic tumor usually presents during the 2nd and 3rd decades of life. The majority of tumors arise in the anterior part of the maxilla (Figure 6A), especially in the canine areas, and there are usually few symptoms apart from a slowly enlarging swelling. Clinical features generally focus on complaints regarding a missing tooth. The lesion usually presents as asymptomatic swelling which is slowly growing and often associated with an unerupted tooth. However, the rare peripheral variant occurs primarily in the gingival tissue of tooth-bearing areas. Unerupted permanent canines are the teeth most often involved in AOT.

(A) Intraoral photograph showing obliteration of the labial vestibule and the expansion of the labial and palatal cortical palate on the left side of the anterior maxilla.

Courtesy: Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, MCODS, Mangalore

Radiographic features

On radiographs it usually appears as a well-defined radiolucency but in some cases calcification within the tumor may produce faint radiopacities (Figure 6B). The lesion is often associated with an unerupted tooth and may simulate a dentigerous cyst (simulating a ‘target’ like appearance).

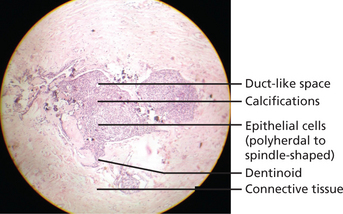

Histopathology

Lesion is well encapsulated and may be solid or partly cystic; in some cases the tumor is almost entirely cystic. It consists of sheets, strands, and whorled masses of epithelium which in places differentiate into columnar, ameloblast-like cells. The columnar cells form duct or tubule-like structures (hence adenomatoid) with the central spaces containing homogeneous eosinophilic material. These are thought to represent abortive attempts at enamel organ formation. There is very little supporting stroma. Small foci of calcification are scattered throughout the tumor and occasionally tubular dentin and enamel matrix may be seen (Figure 7).

Differential diagnosis

Radiologically, it should be differentiated from dentigerous cyst, which most frequently occurs as a pericoronal radiolucency in the jaws. Dentigerous cyst encloses only the coronal portion of the impacted tooth, whereas AOT shows radiolucency usually surrounding both the coronal and radicular aspects of the involved tooth.

Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst

Clinical features

Radiographically, the lesion appears as a well-defined unilocular or multilocular radiolucent area containing varying amounts of radiopaque, calcified material. It may be associated with the crown of an unerupted tooth (Figure 8).

Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor

Keratocystic odontogenic tumor is more universally known as odontogenic keratocyst, but has been renamed as there is sufficient evidence that this lesion actually represents a cystic neoplasm. First described by Philipsen in 1956, the odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) was later designated by the WHO as a keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT) and is defined as ‘a benign uni– or multicystic, intraosseous tumor of odontogenic origin, with a characteristic lining of parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium and potential for aggressive, infiltrative behavior’. WHO recommends the term ‘keratocystic odontogenic tumor’ as it better reflects its neoplastic nature.

Clinical features

KCOTs comprise approximately 11% of all cysts of the jaws. These occur most commonly in the mandible, especially in the posterior body and ramus regions (Figure 8). They almost always occur within bone, although a small number of cases of peripheral KCOT have been reported. Patients may present with swelling, pain and discharge or may be asymptomatic. Distinctive clinical features include a potential for local destruction and a tendency for multiplicity, especially when the lesion is associated with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) or Gorlin–Goltz syndrome. In the recent years, published reports have influenced WHO to reclassify the lesion as a tumor.

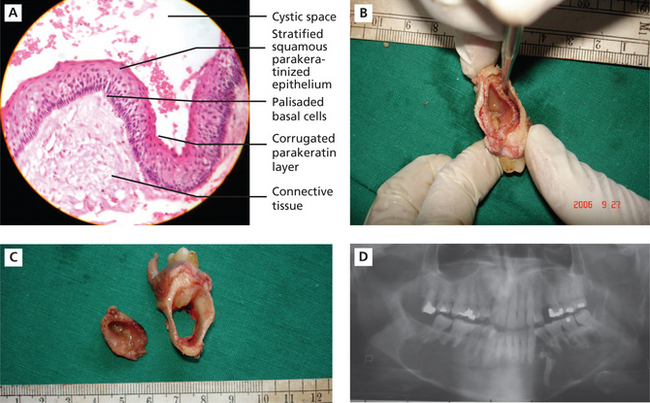

Histopathology

Histologically, these cysts are formed with a stratified squamous epithelium that produces orthokeratin (10%), parakeratin (83%), or both types of keratin (7%). The epithelial lining appears corrugated when viewed under a microscope. A well-polarized hyperchromatic basal layer is observed, and the cells remain basaloid almost to the surface. No rete ridges are present; therefore, the epithelium often sloughs from the connective tissue. The epithelium is thin, and mitotic activity is frequent; therefore, OKCs grow in a neoplastic fashion and not in response to internal pressure. The lumen frequently is filled with a foul-smelling cheese-like material that is not pus but rather collected degenerating keratin (Figure 9A–C).

Figure 9 A.B.C.D (A) Histopathological features of keratocystic odontogenic tumor. (B) and (C) Gross specimens of the resected tumor, showing removal of the cystic lining and the resultant hollowing in the bone. Courtesy: Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, MCODS, Mangalore. (D) Orthopantomograph showing well-defined scalloped radiolucent area extending across the midline. Courtesy: Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, MCODS, Mangalore

Radiographic features

Radiographically, KCOT presents predominantly as a unilocular radiolucency with well-developed sclerotic borders. These may also present as a multilocular radiolucency or unilocular radiolucency at varying ratio. The multilocular appearance can be more of a unilocular with scalloped borders lacking true compartment formation. Odontogenic keratocysts of the maxilla are smaller in size compared to the mandible. When they are large, they tend to expand bone. No difference in site distribution is seen between unilocular and multilocular cysts. These lesions can also present as a small and oval radiolucency between teeth simulating a lateral periodontal cyst. They can also appear as a radiolucency simulating a residual apical periodontal cyst (Figure 9D).

Odontome

History

Recent WHO classification

1. Complex odontome: Malformation in which all the dental tissues are represented, individual tissues being mainly well formed but occurring in a more or less disorderly pattern.

2. Compound odontome: Malformation in which all the dental tissues are represented, in a more orderly pattern; consists of tooth-like structures called the tooth-lets.

Radiographic features

1. First stage is characterized by radiotransparency due to the absence of dental tissue calcification.

2. Second or intermediate stage presents partial calcification.

3. Third or classically radiopaque stage exhibits predominant tissue calcification with a surrounding radio-transparent halo.

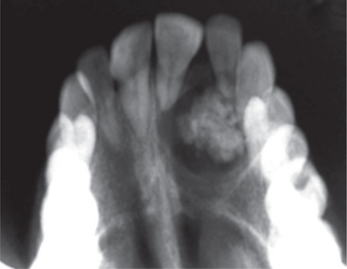

Compound odontomas show an irregular radiopaque image with variations in contour and size, composed of multiple radiopacities corresponding to the so-called denticles. In the complex type of lesion radiopacity is not specific; rather, a disorganized, irregular single or multiple mass is identified (Figure 10).

Prognosis

Odontomas are benign tumors that sometimes produce no symptoms and constitute casual findings of routine radiological studies. However, they usually tend to cause signs and/or symptoms such as delayed eruption. If no signs or symptoms appear then the lesions go undetected. A very infrequent situation in relation to odontomas can be in the form of eruption.

Ameloblastic Fibroma, Ameloblastic Fibrodentinoma and Ameloblastic Fibro-odontoma

Histopathology

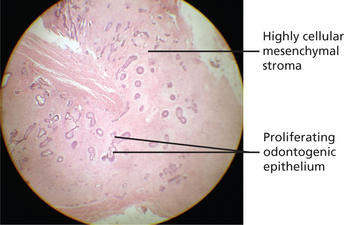

The tumor consists of proliferating strands and clumps of odontogenic epithelium lying in highly cellular fibroblastic tissue resembling the dental papilla of the developing tooth. The epithelial component shows a peripheral layer of cuboidal or columnar cells which encloses a few stellate reticulum-like cells (Figure 11). The appearances are similar to ameloblastoma but the stellate cells are much less abundant and cyst formation is unusual. In some lesions dentin may be present and such tumors may be designated ameloblastic fibrodentinoma. The dentin is usually poorly formed and includes entrapped cells. Tubular dentin is rare.

Odontogenic Myxoma

Clinical features

Commonly seen in the 3rd decade of life with higher prevalence among women, and occurs mainly in the mandibular molar area. Presents as painless swelling or incidental finding.

Radiographic features

Often multilocular with internal osseous trabeculae arranged in ‘tennis racket’ pattern.

Odontogenic Fibroma

Benign Non-Odontogenic Tumors

The primary disease processes that give rise to swellings and tumors of the oral cavity include cysts, mucous extravasations and retention in the minor salivary glands, foci of granulation tissue and inflammation, abscesses and connective-tissue proliferations that are well-defined or encapsulated, as well as infiltrative sarcomas. Both epithelial and connective-tissue disease processes can present as tumors. From a clinical perspective the three most important defining characteristics of any soft tissue swelling are location, coloration, and palpable nature.

Location

Certain diseases tend to occur in specific sites to the exclusion of others, as given in Table 5.

Table 5

Soft tissue swellings according to site

| Site | Type of lesion |

| Lips and buccal mucosa | Fibroma, mucocele, mesenchymal tumor, salivary tumor |

| Gingiva | Parulis, pyogenic granuloma, peripheral fibroma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, peripheral ossifying fibroma, gingival cyst, peripheral odontogenic tumors |

| Palate | Abscess, torus, salivary gland tumor |

| Dorsum of the tongue | Fibroma, granular cell tumor, pyogenic granuloma |

| Ventral aspect of the tongue | Mucocele, ranula, lymphoid aggregates, lymphoepithelial cyst, osteocartilaginous choristoma |

Coloration

It is dependent upon the tissues present in the mass and the depth of the lesion. In general, yellow-appearing lesions are comprised of lymphoid tissue or adipose tissue, red swellings are vascular, blue swellings are mucinous or venous, and brown swellings contain melanin or blood pigments. Lesions with normal mucosal pink coloration are generally composed of fibrous tissues or some other tissues lying deeper in the connective tissues (Table 6).

Table 6

Soft tissue swellings according to their color

| Color | Soft tissue mass |

| Blue-purple | Hemangioma, varix, hematoma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, mucocele, Kaposi sarcoma |

| Red | Hemangioma, pyogenic granuloma, Kaposi sarcoma |

| Brown | Nevus, hematoma, seborrheic keratosis, Kaposi sarcoma, melanoma |

| Black | Melanoma |

| Yellow-orange | Lymphoid aggregates, lymphoepithelial cyst, lipoma, granular cell tumor |

Palpable nature

Based on the consistency they can be grouped as shown in Table 7.

Table 7

Soft tissue swellings according to their consistency

| Palpation characteristic | Swelling |

| Soft, fluctuant | Mucocele, ranula Developmental cysts Sialocysts Gingival cysts Parulis Abscess |

| Soft non-fluctuant | Lipoma Fibroma Organized mucocele |

| Firm fixed | Mesenchymal tumors Granulomas Salivary adenomas Adnexal skin tumors |

| Firm movable | Granular cell tumor Seborrheic keratosis Keratoacanthoma Fibromatosis |

Human papillomavirus (HPV) and oral lesions given in Box 5.

Classification based on the tissue of origin is given in Table 8.

Table 8

Classification based on the tissue of origin

| Epithelial | Papilloma Keratoacanthoma Nevus |

| Connective tissue | Fibroma Giant cell fibroma Peripheral ossifying fibroma Lipoma |

| Vascular tissue | Hemangioma AV fistula Carotid body tumor |

| Lymphatic origin | Lymphangioma |

| Neural tissue | Neurilemmoma Neuroma Neurofibroma Neurofibromatosis |

| Muscular origin | Leiomyoma Rhabdomyoma |

| Bone origin | Osteoblastoma Osteoid osteoma Benign osteoblastoma Desmoplastic fibroma of bone |

| Cartilaginous | Chondroblastoma |

Squamous Papilloma

Clinical features

Exophytic, papillary mass, measuring less than 1 cm, usually pedunculated and soft in texture.

In the form of white lesion, usually solitary; may be multiple.

Squamous papilloma affects the buccal mucosa, soft palate, uvula, tongue and gingiva.

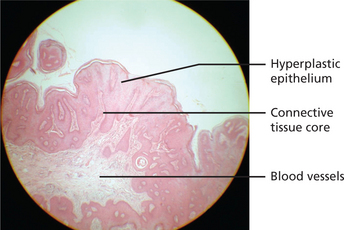

Histopathology

Epithelial hyperplasia with fibrovascular cores may be seen. The papillary projections may be sharp to blunt (Figure 12). Epithelium may be dysplastic in some lesions from HIV-positive patients.

Verruca Vulgaris (Oral Warts)

Infection of mucosal epithelium by members of the human papillomavirus group—usually HPV-2, 4, 6, or 11.

Histopathology

Histological changes can be in the form of surface hyperkeratosis, granulosis and koilocytosis.

AIDS-associated oral warts may appear dysplastic microscopically.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses