13

Oral Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

- the role of bacterial plaque in dental disease

- the methods available to control bacterial plaque

- dietary advice to control caries incidence

- the use of fluoride in caries prevention

- the modification of risk factors to control periodontal disease

- the use of communication skills in oral health evaluation, motivation and promotion

- the effect of general health on oral health

- the genetic predisposition to periodontal disease

As discussed in Chapter 11, the main oral diseases of concern to the dental team are as follows.

- Dental caries – the bacterial infection of the mineralised tissues of the tooth.

- Gingivitis – the inflammation of the gingival tissues at the neck of the tooth.

- Periodontitis – the inflammation of the supporting structures of the tooth.

- Oral cancer – the malignancy specific to the oral cavity that presents as squamous cell carcinoma (this accounts for 90% of oral cancers, although others do occur).

A huge part of the day-to-day work of the dental team is to educate patients in the risk factors of these four diseases, so that they can avoid their initial onset or avoid their recurrence once treatment has resolved any diagnosed disease that was present.

The success of this ‘dental education’ depends on various factors, listed below, some of which are outside the control of the dental team.

- Communication skills – irrespective of how important the advice is to the patient, if it is delivered in a way that the patient cannot understand, it will not be followed.

- Age group – the style of communication and the advice to be given will vary between age groups, and these groups are generally divided into:

- adults

- young people

- children.

- Patient motivation – despite the best attempts by the dental team, some patients are simply uninterested in their own oral health, and are unwilling to participate in efforts to assist them in achieving good oral health.

- General health – some medical and physical conditions (including old age) will affect the likelihood of oral disease development in some patients, while other conditions will affect the patient’s ability to carry out effective oral hygiene methods.

All of these factors and their influence on the patient’s standard of oral health will be discussed here, but throughout and in following chapters it will be seen that the old adage holds true:‘Prevention is better than cure’. Self-help by patients, supported by the robust oral health efforts of the dental team, is much easier to achieve and obviously better than suffering the pain, misery and expense of dental disease and its necessary treatment.

Bacterial plaque as a risk factor in dental disease

As discussed in detail in Chapter 11, the presence of bacterial dental plaque is a prerequisite for the development of all three of the main dental diseases (dental caries, gingivitis and periodontitis), in addition to other causative factors as described below.

The causative factors of dental caries are:

- a diet containing a high proportion of non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMEs)

- poor oral hygiene allowing the accumulation of dental plaque and the bacteria it contains

- stagnation areas of the teeth themselves such as occlusal fissures, overhanging restorations and abutments with dentures and orthodontic appliances

- the action of the bacteria on the NMEs to produce acid, which demineralises the tooth structure and allows cavities to develop.

The causative factors of gingivitis and periodontitis are:

- poor oral hygiene which allows the accumulation of dental plaque, specifically in the gingival crevice and periodontal pockets, and on any pre-existing surface of tartar

- the existence of stagnation areas, including the gingival crevice, which allows the plaque to accumulate specifically around the necks of the teeth against the gingiva

- failure to treat and eradicate the subsequent gingivitis allows inflammation of the periodontal supporting structures, leading to periodontitis.

Dental plaque

The full name is bacterial dental plaque but in general usage, and hereafter, it is simply referred to as plaque. As it plays such an important part in dental disease, its origin and effects should be clearly understood by all whose work involves dental treatment or dental health education.

Plaque is a thin transparent layer of saliva, oral debris and normal mouth bacteria which sticks to the tooth surface and can only be removed by cleaning. It is replaced within a few hours by a new deposit of plaque, and its presence in the mouth may be regarded as a natural occurrence. The harm it causes comes from food debris which sticks to the plaque during meals and snacks and provides a plentiful supply of nourishment for its bacteria and other micro-organisms. They accordingly flourish, the plaque grows thicker, and caries and periodontal disease begin.

Which of the two diseases predominates depends on the following factors, but the plaque is the same whichever disease occurs.

- The site of the plaque.

- The diet, and specifically the presence of NMEs.

- The age of the patient.

If the plaque is in contact with a tooth surface, caries will develop there unless the plaque is removed. If the plaque is in contact with the gingiva, gingivitis and then periodontitis will develop unless the plaque is removed.

Caries is mainly a disease of children and young adults whereas periodontal disease predominates in later life. The difference is caused by the rate at which the two diseases progress. Caries can cause loss of teeth within a few years whereas periodontal disease may take decades to have the same effect. By the time periodontal disease has reached an advanced stage, the earlier onslaught of caries has already been overcome and is no longer a problem, as the teeth which were susceptible to caries have already been treated by exposure to fluoride, fissure sealing, filling or other restoration, or extraction.

Another reason explaining which disease predominates in each age group is the diet they tend to follow. Consumption of sweets and sugary food and drinks is probably far greater, and far less controlled, in children and young people, and their teeth are consequently much more vulnerable to caries. However, it must not be assumed that adults and older people are immune to caries. It still occurs if childhood patterns of unrestricted, indiscriminate consumption of sweets persist. A typical example is the adult smoker who continually sucks mints after giving up the habit for health reasons – and then develops rampant caries affecting the buccal tooth surfaces, as the sugary mints dissolve and wash over the teeth.

Likewise, an aggressive form of periodontal disease can also occur in juveniles, although it is relatively uncommon.

The role of saliva in dental disease development

As discussed in Chapters 10 and 11, saliva is the watery secretion from the salivary glands that bathes the oral cavity to keep the tissues moist. It also protects against:

- caries by promoting remineralisation of early enamel caries

- periodontal disease by its cleansing and antibacterial properties

and promotes overall health of the mouth by its lubricating and cleansing effects.

People suffering from the condition of xerostomia (or dry mouth) do not benefit from these effects and are accordingly at much greater risk of both caries and periodontal disease. This disorder is covered in greater detail later.

Prevention of dental disease

As indicated previously, caries occurs due to a combination of certain types of bacteria being present within dental plaque that use NMEs to produce acids that cause enamel demineralisation, There are therefore three main areas of caries prevention available to the patient and dental team.

- Increase the tooth resistance to acid attack – by incorporating fluoride into the enamel structure.

- Modify the diet – to include fewer cariogenic foods and drinks, and to reduce their frequency of intake.

- Control the build-up of bacterial plaque – practise its regular removal by using good oral hygiene techniques.

The main cause of periodontal disease is consistently poor oral hygiene, along with contributory factors such as smoking, and in some cases an unfortunate genetic predisposition to periodontal problems.

The prevention of periodontal disease can be achieved in most patients, whereas it can only be controlled in others.

- Control the build-up of bacterial plaque –practise its regular removal by using good oral hygiene techniques.

- Modify the contributory factors – by giving advice on smoking cessation, for instance.

- Control the host response – in patients predisposed to periodontal problems, by more frequent dental attendance for monitoring and evaluation, and intervention where necessary.

It can be seen that controlling the build-up of bacterial plaque is a common requirement in the prevention of both dental caries and periodontal disease (including gingivitis). Educating patients in how to successfully remove bacterial plaque, on a daily basis and for the rest of their lives, is the most important aim of the dental team in helping their patients maintain a good standard of oral health.

Control of bacterial plaque

Plaque forms within hours on newly cleaned tooth surfaces, due to the action of oral bacteria on foods. Unless removed from these areas, the plaque will allow dental caries to develop, while that formed around the gingival crevice will be involved in the onset of gingivitis and eventually periodontitis.

Controlling bacterial plaque on a daily basis is the main method by which patients can promote their oral health. It is the role of the dental team to ensure that patients are taught the correct oral hygiene methods suitable to them, and that they carry them out on a frequent enough basis to avoid damage to their oral health.

Plaque can be easily removed by the patient at home by carrying out a combination of the following oral hygiene techniques on a daily basis.

- Tooth brushing, using a recommended toothpaste.

- Interdental cleaning.

- Using suitable mouthwashes.

Figure 13.1 Sonicare toothbrush.

Tooth brushing

Tooth brushing is the method used to remove supragingival plaque and food debris from the smooth surfaces of the teeth – that is, the buccal, labial, lingual, palatal and occlusal surfaces, as well as the gingival crevice. Unless the patient has widely spaced teeth, the interdental areas will require special techniques of cleaning to remove plaque efficiently.

- Toothbrushes with a small head and multi-tufted medium nylon bristles are probably the most effective for the vast majority of patients.

- Good-quality, rechargeable electric toothbrushes take the need for consistently good manual techniques away from the patient, and are more likely to achieve prolonged high standards of oral hygiene (Figure 13.1).

- The brush is rinsed to wet the bristles and a portion of the recommended toothpaste added (see below).

- Each dental arch is divided into three sections: left and right sides, and front.

- Side sections are subdivided into buccal, lingual and occlusal surfaces; front into labial and lingual.

- When instructing patients, these areas should be referred to in terms the patient can understand – such as ‘cheek side’, ‘tongue side’, ‘lip side’, and so on.

- This amounts to eight groups of surfaces in each jaw, and at least 5 sec should be spent on each group.

- Egg timers or similar devices can give the patient an idea of how long the recommended 2-min brushing cycle actually is. Some electric brushes have a timer incorporated into their design.

- The patient should be encouraged to develop their own start and endpoint within the oral cavity and then follow it systematically at each brushing session, so that a methodical routine is developed; so perhaps lower left side (all surfaces) followed by lower front (all surfaces) and then lower right side (all surfaces), before moving to the upper arch.

- Each area is brushed in turn and the mouth is then cleared by spitting out the toothpaste and oral debris.

- The patient should be instructed not to rinse the mouth out, as this removes the residual toothpaste and prevents its chemical constituents from continuing to act in the mouth – this is particularly important with fluoridated toothpastes.

- Parents will need to perform effective tooth brushing on children up to the age of around 8 years, to ensure that all plaque is removed and to teach the child how to brush correctly (Figure 13.2).

- Brushes should be rinsed afterwards and allowed to dry, and they only have a limited life and need replacement every few months as the bristles curl down and render the brush ineffective (Figure 13.3).

Figure 13.2 Supervised child tooth brushing.

Figure 13.3 New and worn toothbrush.

Toothpastes

A huge variety of toothpastes is available, from shops’ own brands to specialised ones from oral health product suppliers, with ingredients to fight all aspects of common oral disease. Individual recommendations should be given for any patient requesting advice from the dental team as to the most suitable product (Figure 13.4). This may vary from time to time as the patient may experience certain oral problems throughout life.

- Over 95% of toothpastes available in the UK contain fluoride, as sodium monofluorophosphate and sodium fluoride at 1000 parts per million (ppm).

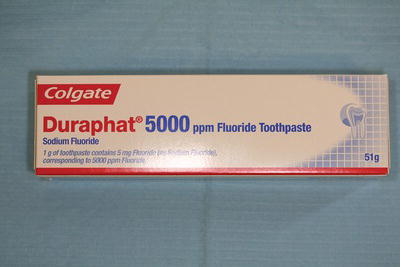

- High fluoride toothpastes contain between 2800 ppm and 5000 ppm, for use by adult patients with an existing high caries rate or an excessive risk of developing caries (Figure 13.5).

- Several other toothpastes contain ingredients specifically to slow down calculus formation.

- Many now contain the substance triclosan combined with zinc, which acts as an antiseptic plaque suppressant.

- Some toothpastes are specifically formulated to help relieve sensitivity, and contain ingredients such as stannous fluoride (Figure 13.6).

- Others are advertised as ‘whitening toothpastes’ and remove surface tooth staining by the use of abrasives or more recently by the use of biological enzyme systems.

- More recent developments have included toothpastes designed to help protect teeth against acid erosion (Figure 13.7).

Figure 13.4 Types of toothpaste.

Figure 13.5 High fluoride toothpaste.

Figure 13.6 Pro-Relief toothpaste.

Figure 13.7 Pronamel toothpaste.

Interdental cleaning

However good the tooth-brushing technique, it is still impossible to clean interdental spaces perfectly with a toothbrush alone, unless a specialist electric brush is used. Consequently, the mesial and distal contact areas between adjoining teeth are more prone to developing caries and periodontal disease. To clean the interdental areas adequately, several oral health aids are available to assist patients to remove plaque that has formed here.

- Dental floss and dental tape are thread-like aids used to achieve interdental plaque removal; however, correct usage depends to some extent on the patient’s manual dexterity and on receiving sound oral health instruction (Figure 13.8).

- ‘Flossette-style’ handles hold the length of floss in place for the patient so that they can floss with one hand, therefore making the procedure less cumbersome, especially for posterior teeth where access is difficult for the majority of patients (Figure 13.9).

- Interdental brushes are a typical ‘bottle-brush’ design which are able to clean in spaced interdental areas, as well as around the individual brackets of fixed orthodontic appliances (Figure 13.10).

- Woodsticks (although they may also be plastic!) dislodge solid pieces of food debris from interproximal areas, as well massaging the gingivae area. However, their use should be restricted to competent adults whenever possible, as they can easily be stuck into the gum and cause problems if used incorrectly.

Figure 13.8 Dental flosses and tapes.

Figure 13.9 Interdental flossettes.

The aim of all these interdental aids is to dislodge food particles and accumulated plaque from the interdental areas of the teeth, so that the debris can be swallowed or removed from the oral cavity. As the plaque sticks to the tooth surface itself, the cleaning aids should be physically pulled across the mesial and distal tooth surfaces to remove this biofilm layer, so the majority of patients will require demonstrations in the correct technique by a member of the dental team. In particular, dental floss and tape needs to be ‘wrapped around’ the separate tooth surfaces to adequately clean them, and this requires a certain level of manual dexterity by the patient (see Figure 11.19).

Figure 13.10 Interdental brush detail.

Figure 13.11 Types of mouthwash.

Even when used correctly, woodsticks are the least effective method of interdental cleaning available, and other techniques should be recommended to the patient wherever possible.

Mouthwashes

A wide range of mouthwashes is currently available, ranging from shops’ own brands to specialised products from dedicated oral health product suppliers (Figure 13.11). Each patient should have specific products recommended for use by the dental team, once their particular oral health needs have been assessed.

- General-use mouthwashes contain various ingredients to promote good oral hygiene, including:

- sodium fluoride – to provide topical fluoride application to the teeth

- triclosan – a chemical that suppresses the formation of plaque in the oral cavity.

- Others are specialised for use on sensitive teeth (Figure 13.12).

- Some are used specifically in the presence of oral soft tissue inflammation as a first aid measure, or after oral surgery, and contain hydrogen peroxide which helps to eliminate anaerobic bacteria (Figure 13.13).

- Specialised mouthwashes are also available for patients suffering from both acute and chronic periodontal infections, and contain chlorhexidine which is an antiseptic plaque suppressant (Figure 13.14).

Figure 13.12 Pro-Relief mouthwash.

Other methods of plaque removal

After eating a meal, tooth brushing may not always be possible until several hours later, by which time plaque will have formed and possibly started to cause damage. Obvious examples are after eating lunch at school or at work, or while out for a meal in the evening.

In these situations, loose food debris can be removed by using sugar-free chewing gum or finishing the meal with a detergent food and/or a piece of cheese. Detergent foods are raw, firm, fibrous fruits or vegetables, such as apples, pears, carrots and celery. By virtue of their tough fibrous consistency, they require much chewing and stimulate salivary flow, thereby helping to scour the teeth clean of food remnants. Although plaque is unaffected by detergent foods, they can remove some of the food debris which nourishes all plaque bacteria and enables some of them to produce acid. Although cheese at the end of a meal has no direct detergent effect, it stimulates salivary flow, neutralises acid and enhances remineralisation of enamel, due to its calcium content. Hard cheeses are more beneficial than soft cheeses.

Figure 13.13 Peroxyl mouthwash.

Figure 13.14 Corsodyl daily mouthwash.

The excessive use of chewing gum should be discouraged in all patients where evidence of attrition or bruxing appears. Its use should be confined to immediately after a meal only, and not continually throughout the day.

Prevention of dental caries

Two other factors were noted previously with regard to preventing dental caries, and they will both be discussed here.

- Increase the tooth resistance to acid attack.

- Modification of the diet.

Increase the tooth resistance to acid attack

The outer layer of the tooth, the enamel, is made up of inorganic crystals of calcium hydroxyapatite arranged as prisms running from the amelodentinal junction to the tooth surface (see Chapter 10). It was discovered many years ago that the incorporation of fluoride into and onto the tooth structure resulted in the replacement of the hydroxyapatite crystals by fluorapatite crystals. This new chemical structure of the tooth was found to be much more resistant to the damage caused by the weak organic acids formed by plaque bacteria – in other words, the fluoride protected the teeth from developing caries so easily.

Fluoride is therefore the single most important salt in the battle against dental caries. It occurs naturally in the water in some areas, and is added artificially to water supplies in other areas during the process of water fluoridation, as an oral health measure to aid in the reduction of caries incidence.

Fluoride can be taken into the enamel structure by the direct application of various oral health products onto the teeth, called topical fluoride application, or by being taken internally with food and drink products, called systemic fluoride application.

Besides its action of reducing the solubility of enamel to acids, by the formation of fluorapatite, fluoride also has an inhibitory effect on the feeding rate of oral bacteria. This effect results in the production of lesser amounts of weak acids and polysaccharides to initiate the carious attack.

The protective effect of fluoride on the teeth is at its best after they have formed and recently erupted into the oral cavity, before any carious damage has begun. Many oral hygiene products containing fluoride are now available, to allow their regular use by the general public throughout their lifetime, so that the protective effect of fluoride on the teeth is constantly ‘topped up’.

Topical fluorides

These are administered externally to the tooth surface, either by the patient or the dental team, to provide a continual source of fluoride directly onto the enamel.

- Fluoride toothpastes containing the current recommended dose for all patients of 1000 ppm, up to 5000 ppm for use by adults at high risk of developing caries (see Figure 13.5).

- A minimum of twice-daily brushing is advised to achieve maximum benefits.

- Patients should be advised not to rinse out after brushing, as it washes the fluoride away and is therefore less effective.

- Fluoride mouthwashes for regular use by those with a high caries risk, and for those undergoing orthodontic treatment (Figure 13.15).

- Dental floss and tape impregnated with fluoride, for delivery directly to the interproximal areas.

- Fluoride gels applied in trays over all the teeth for several minutes; they are administered at each examination appointment and are especially useful for patients with special needs and a high caries risk.

- Children with rampant caries.

- Patients with medical conditions such as haemophilia and heart defects which would make tooth extraction dangerous.

- Patients who are too handicapped to achieve adequate oral hygiene.

- The technique has two stages: first, a thorough polish to remove/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses