Chapter 13

Localised Onlay Bone Grafts

Introduction

Autogenous onlay block grafts are required to reconstruct a minor deficiency of the alveolar ridge for aesthetic and/or biomechanical reasons. The likely causes of minor deficiencies are:

- • congenital deficiencies: caused by congenitally missing single teeth

- • disuse atrophy: caused by tooth loss, which is likely to be more pronounced in specific biotypes

- • minor trauma: leading to tooth loss and possibly alveolar bone loss

- • infection: caused by localised periodontal issues, endodontic failures, fractured roots or failed implants and bone grafts.

Assessment of Localised Bone Deficiency

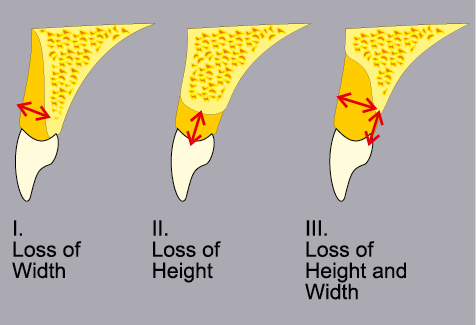

Assessment of the residual ridge should be carried out as described above, using appropriate diagnostic measures. The quantity of bone should be measured in relation to the future position of the tooth. Local bone deficiencies may be classified very simply according to practical requirements (Fig 13-1):

- • loss of width

- • loss of height

- • loss of height and width.

Fig 13-1 Classification of bone deficiencies based on the type of defect, namely height, width or height and width.

For larger deficiencies, the volume of bone that needs to be replaced must also be assessed in relation to any of the available classifications of jaw atrophy that the clinician is familiar with. This will be dealt with in a separate chapter (Chapter 14). The type of bone reconstruction and the position of the bone graft will influence the design of the flap used to ensure wound closure.

Loss of Width

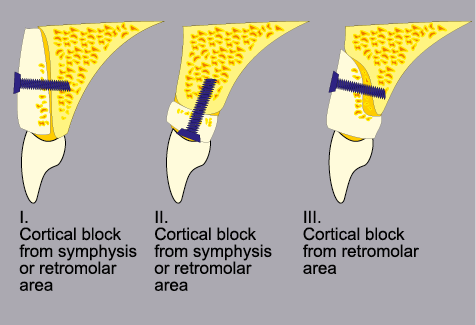

Deficiencies in ridge width may be corrected using bone from either of the two intraoral donor sites: the ramus or the symphysis (Fig 13-2, I).

Sufficient bone can usually be obtained from each ramus for up to four implants and from the symphysis for four implants. An increase in width of 2–6 mm can be achieved with bone from the ramus and between 2 and 6 mm with bone from the symphysis. This, however, depends on the actual anatomy of the region, the assessment of which will be covered in a subsequent section (Figs 13-3–13-5).

Fig 13-2 The type of graft required for the correction of the three types of deficiency illustrated by the classification in Fig 13-1. Screws are illustrated here as the primary form of fixation, to prevent micro-movement and sequestration of the graft.

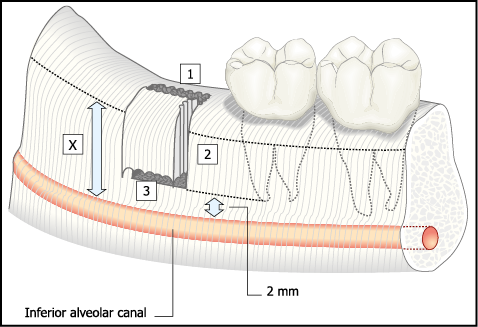

Fig 13-3 The harvesting of a bone graft from the ramus (lateral aspect). Measurements, clinical and radiographic, must be made from the external oblique ridge. A clearance of 2 mm from the inferior alveolar canal must be allowed. In addition, compensation for any distortion of the radiograph must be made. Bone cuts must not be extended beyond the critical depth X (see also Fig 13-6).

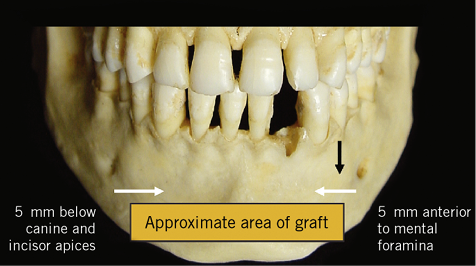

Fig 13-4 Anterior view of the mandible outlining the area where a graft can safely be harvested, depending upon the local anatomical limitations.

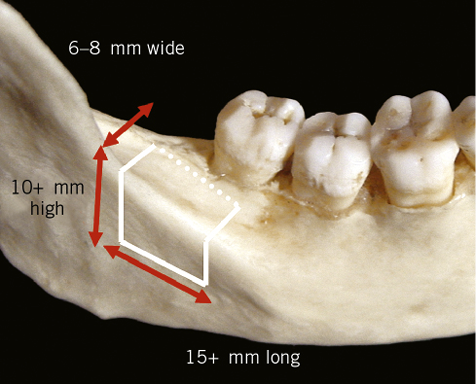

Fig 13-5 View of the lateral aspect of the mandible showing the typical dimensions for a graft designed to correct a deficiency in height and width (Class III).

Loss of Height

Sufficient bone for up to four implants can be harvested from the symphysis and for up to four implants from each ramus. An increase in height of up to 4 mm can usually be achieved (Fig 13-2, II).

Loss of Width and Height

Although it is possible on occasion to use the symphysis to increase height and width, its morphology does not always lend itself to the 3D reconstruction of a deficient ridge. The ramus with its external oblique ridge, however, is ideally shaped to provide a graft that will reconstruct a ridge deficiency (Fig 13-2, III). Typically, it is possible to achieve an increase in width of up to 6 mm and an increase in height of 4 mm. Each ramus will provide sufficient bone to construct the ridge for two implants. The local morphology of the ramus will, of course, need to be assessed carefully.

Careful assessment of the width of the entire alveolar ridge must be made in order to ensure that sufficient bone is available to extend the graft towards the basal part of the ridge should the entire alveolar ridge be insufficient in width. This will influence the selection of the donor site.

Where the tooth is present, certain indicators will determine the likelihood of having to use bone grafts prior to or at the time of extraction of the tooth. Loss of more than half of the labial plate increases the likelihood of a bone graft being necessary, particularly where aesthetics are critical. Loss of palatal bone is a significant indicator for a deficiency in height, requiring a bone graft.

Assessment of the adjacent teeth and the interdental bone level must not be overlooked as bone can only be built up to or marginally above the level of bone attachment of the adjacent teeth. This is because the graft must not be in direct contact with the tooth.

Assessment of Donor Site

Symphysis

Assessment of the symphysis as a donor site is carried out radiographically, using panoramic radiographs and lateral cephalographs following correction for magnification. A clearance of 5 mm below the tips of the roots is advised to minimise the risk of damage or the interruption of sensory innervation. The position of the canine root tips should be established accurately if extensive grafts are going to be required. The lower limit of the graft should not extend beyond the maximum convexity of the mental process in order to maintain the patient’s facial profile (Fig 13-4).

Ramus

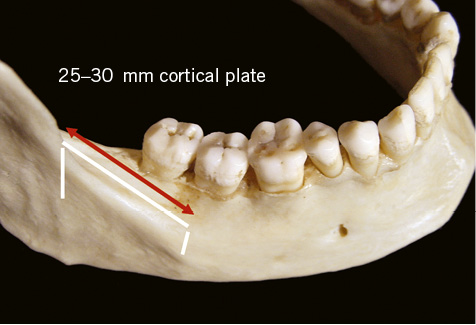

A panoramic radiograph is used for the assessment of the ramus in conjunction with a physical examination of the external oblique ridge. When CT is available, interpretation of the distance between the inferior alveolar ridge and the external oblique ridge should be undertaken, but with caution as the orientation of the cross-sectional images may not be perpendicular to the external oblique ridge or the inferior alveolar canal. This would give an incorrect measurement of the distance between the two structures. The position of the inferior alveolar nerve in the bucco-lingual dimension is useful information that can be obtained from this investigation.

Other factors that should be taken into account are:

- • all measurements must be made from the external oblique ridge and not the alveolar ridge (Fig 13-3); the height of the bone available for harvesting will affect the size of the surface area of the recipient site that can be covered

- • the presence of wisdom teeth will limit the width and length of the bone graft that can be obtained

- • the width between the external oblique ridge and the lingual wall of the mandible will also determine the width of the bone graft that can be harvested (Figs 13-5 and 13-6).

Fig 13-6 Lateral aspect of the mandible showing the typical dimensions of a graft designed to correct a deficiency in either width or height (Class I or II). Generally deficiencies requiring repair for up to four implants can repaired.

Extraoral Sites

When insufficient bone is available at one or more intraoral donor sites an extraoral donor site should be considered (Chapter 14).

Treatment Sequence

Treatment can be started on a healed site once the diagnostic procedures have been completed, providing that the mouth is free of disease.

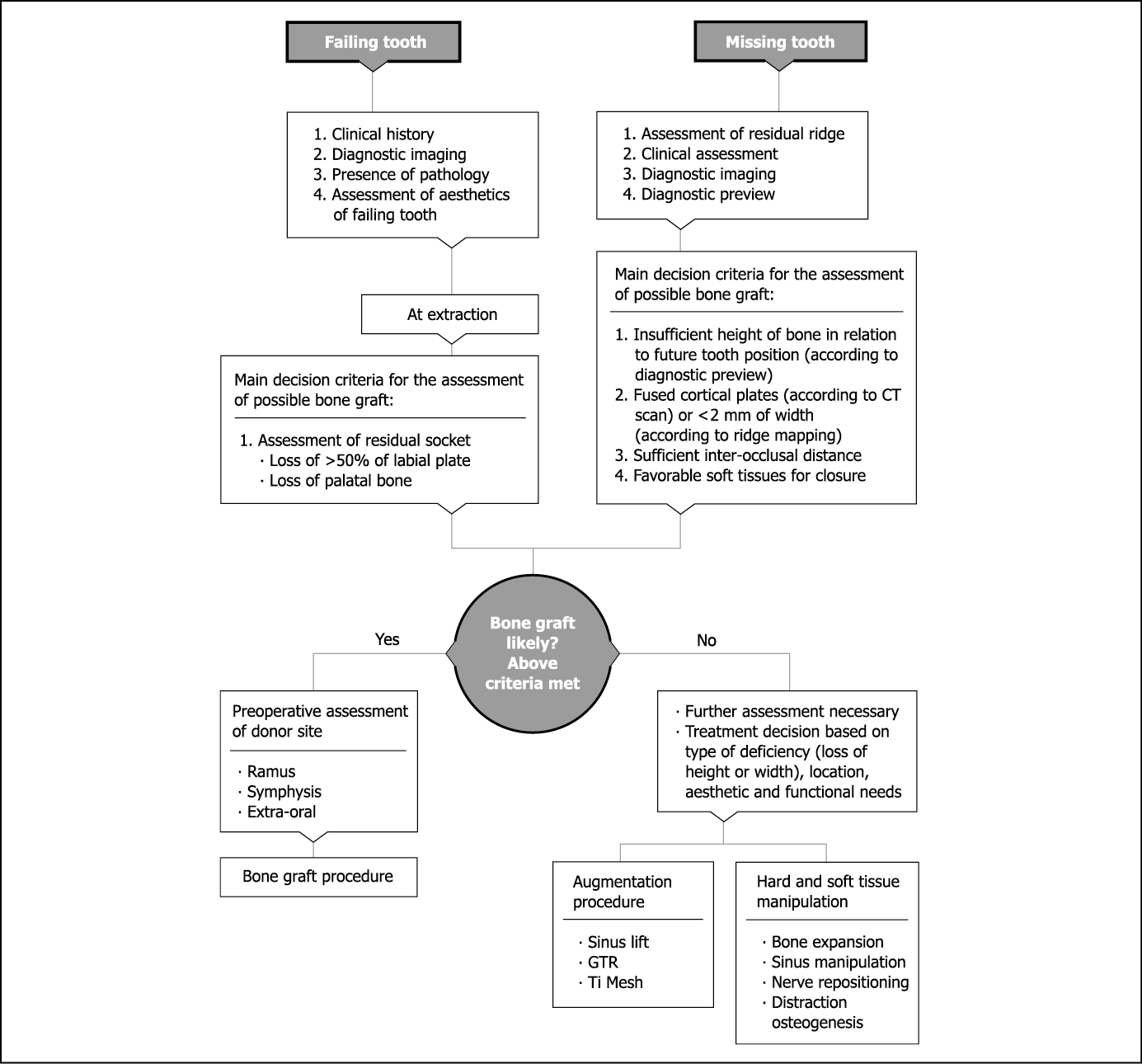

Following extraction and where a bone graft is anticipated, a period of 8 to 12 weeks should be allowed for soft tissue healing and adequate blood supply to establish. Completion of healing should be monitored, and the mucosa covering the ridge should be free of depressions and fissures. This period may be used to confirm the need for a bone graft based on radiographic examination and the appearance of the provisional restoration in relation to the gingival tissues. Flowchart 13-1 summarises the main criteria that can be used to assess the need for a bone graft.

Flowchart 13-1 Assessment for bone grafts.

Where there is uncertainty about the need for a bone graft, a healing period of six months allows the bone to mature sufficiently that an appropriate decision can be made. Assessment can then be made as to whether conventional placement or bone expansion is possible. The likelihood of healing is much higher where the labial cortical plates are thicker and is likely to be poorer where thin vestibular cortical bone overlies prominent roots with interdental depressions. In the latter, patients often have scalloped gingival contours, whereas patients with thick labial cortical plates generally have flat gingival contours. The sequence of treatment is shown in Table 13-1.

Table 13-1 Sequencing of treatment

|

Step |

Sequence |

|

1 |

Extraction (assessment) |

|

2 |

Soft tissue healing (8–12 weeks) |

|

3 |

Recipient site: incision, reflection, measurement |

|

4 |

Donor site: incision, reflection, marking |

|

5 |

Harvest graft (oversized) |

|

6 |

Fit graft (modify graft and recipient site) |

|

7 |

Fix graft (screw or plate) |

|

8 |

Close recipient site (advance soft tissue) |

|

9 |

Close donor site |

|

10 |

Assess bone healing (radiograph); remodelling: 2–4 months, up to 6 months for membrane |

|

11 |

Implant insertion into grafted and recipient |

|

12 |

Corrective soft tissue surgery if necessary |

|

13 |

Expose |

|

14 |

Corrective soft tissue surgery if necessary |

|

15 |

Soft tissue healing (4 weeks) |

|

16 |

Restore |

Surgical Protocol

The preoperative assessment should have determined the amount of bone that will be required and have identified a potential donor site. Based on the information gained, a decision regarding the type of incision has to have been made before starting surgery to ensure closure without tension over the graft. This will also be influenced by which region of the mouth is being treated.

Access to Recipient Site

Surgery is started at the recipient site in order to identify the precise shape of the graft that will be required and to measure the dimensions of the deficiency. Once the recipient site has been prepared, donor-site surgery can be started and the bone harvested and transferred to the recipient site within a minimum period of time.

Maxilla

The most common bone deficiency of the maxilla occurs on the labial aspect of the ridge. A remote palatal incision is used to expose the deficiency in the ridge and labial aspect of the maxilla (Fig 13-7). If the loss of bone is on the palatal aspect of the maxilla, a palatal incision must not be used. A crestal or labial incision is indicated under these circumstances (Figs 13-8–13-13).

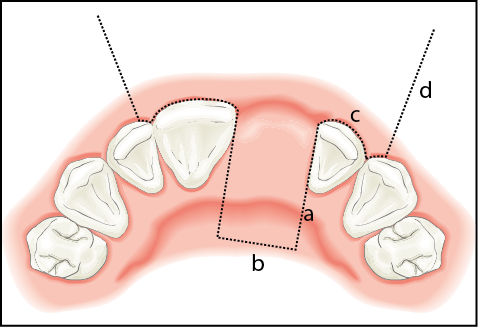

Fig 13-7 Remote palatal incision required for the recipient site for a deficiency in the anterior maxilla. The incision was made in the following sequence: a, the vertical component, approximately 10 mm; b, the horizontal bevelled component made with Blake’s knife; c, the intrasulcular incision; and d, the vertical release incision, including papilla.

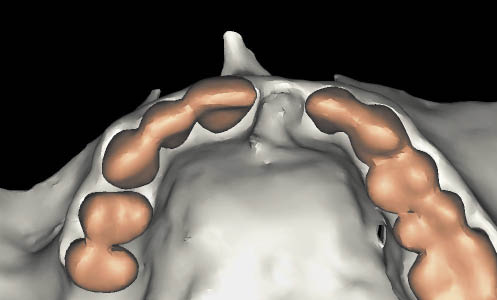

Fig 13-8 CT 3D view showing the palatal defect.

Fig 13-9 Occlusal view showing soft tissue defect overlying the bony defect as well as the outline of the crestal incision.

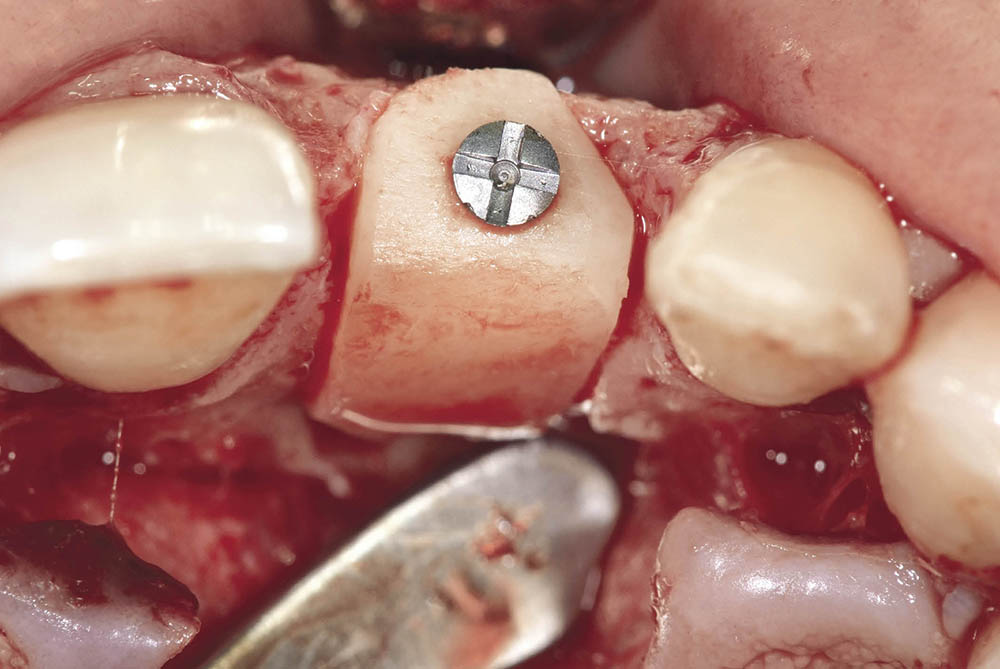

Fig 13-10 Block graft harvested from the ramus in situ for repair of the palatal defect.

Fig 13-11 Labial review of the graft in situ showing a residual defect, which will be filled with particulate cortical chips.

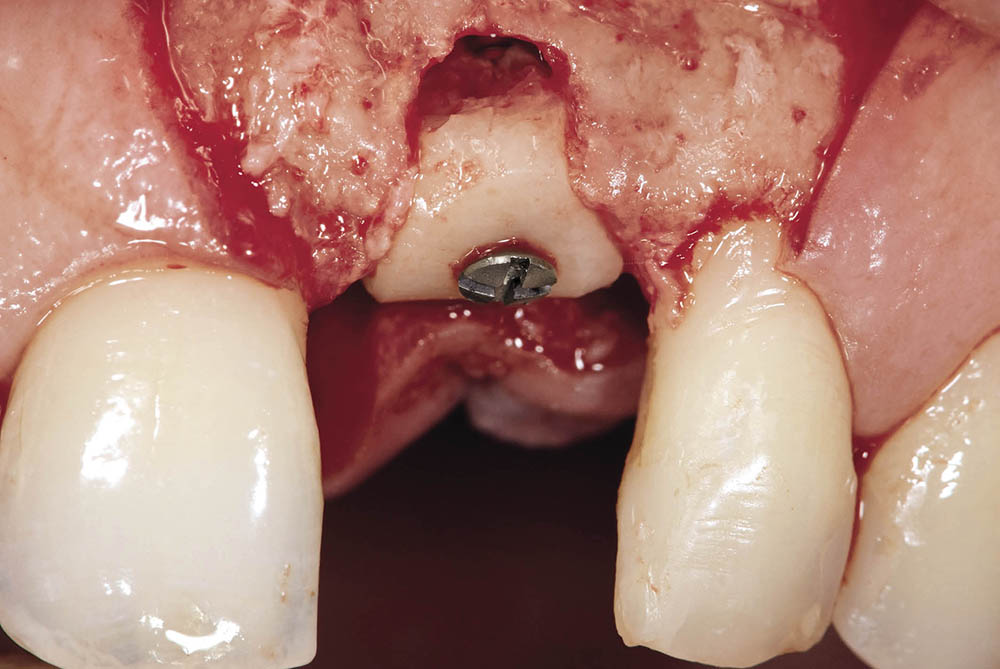

Fig 13-12 Healing of soft tissues at one week, showing no exposure of the graft and demonstrating the efficacy of everted tissue closure using horizontal or vertical mattress sutures.

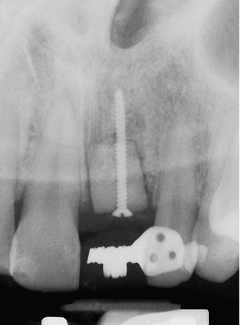

Fig 13-13 Post-operative radiograph showing graft and the fixation screw. This baseline radiograph will be used to monitor the maturation of the graft.

Access to the ridge is gained via a remote palatal incision made approximately 1 cm from the crest of the ridge. The perpendicular component of the incision into the palate is made with a number 15 blade in a conventional handle. The incision is extended within the cervical margin to the distal papilla of the adjacent teeth. A vertical release incision on the labial aspect, one tooth away from the recipient site, is made to include the papilla. The vertical release incision is extended into the unattached mucosa. The palatal incision parallel to the crest is made with a Blake’s knife (blade number 15) and is bevelled towards the crest to allow for easy closure of the wound. The buccally based flap is elevated using a curved elevator (Dentsply Friadent) to expose the crest of the ridge.

A fine periosteal elevator is used to lift the periosteum from the area of bone loss and to elevate the gingival margin from the adjacent teeth without perforating this critical area. The papillae are carefully elevated using a papilla elevator (Fig 13-14).

Fig 13-14 Curved elevator (top instrument) for the elevation of a buccally based flap. Papilla elevator (bottom instrument) for the atraumatic elevation of papillae in an aesthetically critical zone. These instruments are also part of the sinus lift kit (Fig 15-22, p. 314).

The reflection of the buccally based flap is extended and reflected off the appropriate anatomical structures.

- • Anterior maxilla. For grafts in the anterior region, the reflection of the buccally based flap is extended towards the anterior nasal spine and the piriform rim. For grafts that are more laterally placed the flap is extended towards the zygomatic arch. This will normally provide sufficient tissue for closure without the need for periosteal release incisions. Care must be taken while making vertical release incisions and reflecting the flap in the region of the infra-orbital foramen to avoid damage to the structures emanating from the foramen.

- • Posterior maxilla. Any palatal incision in the posterior maxilla must be carried out with care in order to avoid severing the branches of the greater palatine vessels or nerves. A split-thickness incision should be used here, the periosteum being incised near the crest of the ridge. No distal vertical release incision in an unbound saddle is needed in the posterior maxilla, as the parallel component of the palatal incision can be extended distally over the ridge distal to the tuberosity. Any periosteal release carries the risk of damage to the parotid duct, which must be identified and avoided.

Mandible

For localised bone deficiencies of the mandibular ridge, a crestal incision is usually the approach of choice. Care needs to be exercised whenever a vertical release incision needs to be made in the area of the mental foramen.

- • Anterior mandible. In the anterior mandible, flap advancement can be carried out using a periosteal release on the labial aspect and periosteal reflection on the lingual side. Clearly care must be taken not to damage any vital structures in this area, such as the mental nerve, branches of the sublingual artery, muscle attachments and the sublingual duct.

- • Posterior mandible. A periosteal release incision in the labial and lingual area of the posterior mandible is fraught with serious risk to several vital structures, and sharp dissection should, therefore, not be contemplated. Some of the structures of particular concern/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses