CHAPTER 13 Local Anesthesia and Pain Control for the Child and Adolescent

Investigators have found that injection is the dental procedure that produces the greatest negative response in children. Responses become increasingly negative over a series of four or five injections. Venham and Quatrocelli1 have reported that a series of dental visits sensitized children to the stressful injection procedure while reducing their apprehension toward relatively nonstressful procedures. Thus dentists should anticipate the need for continued efforts to help the child cope with dental injections.

TOPICAL ANESTHETICS

Ethyl aminobenzoate (benzocaine) liquid, ointment, or gel preparations are probably best suited for topical anesthesia in dentistry. They offer a more rapid onset and longer duration of anesthesia than other topical agents. They are not known to produce systemic toxicity as oral topical anesthetics, but a few localized allergic reactions have been reported from prolonged or repeated use. Examples of commercially available products are Hurricaine (Beutlich L.P. Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Chicago, Ill), Topicale (Premier Dental Products, Inc., Plymouth Meeting, Pa), and Gingicaine (Gingi-Pak, Inc., Camarillo, Calif). All three products are available in gel form. Gingicaine is also available in liquid and spray forms, and Hurricaine is available as a liquid. Topicale is available in ointment form.

JET INJECTION

Jet injection produces surface anesthesia instantly and is used by some dentists instead of topical anesthetics. The method is quick and essentially painless, although the abruptness of the injection may produce momentary anxiety. This technique is also useful for obtaining gingival anesthesia before a rubber dam clamp is placed for isolation procedures that otherwise do not require local anesthetic. Similarly, soft tissue anesthesia may be obtained before band adaptation of partially erupted molars or for the removal of a very loose (soft tissue–retained) primary tooth. O’Toole has reported that the Syrijet may be used instead of needle injections for nasopalatine, anterior palatine, and long buccal nerve blocks.2

A more recently developed jet injection device reported by Duckworth and colleagues delivers a dose of dry powdered anesthetic to the oral mucosa.3 In this study, an initial trial with 14 adult subjects, successful topical analgesia without tissue damage was reported. More clinical trials are required before substantial claims can be made regarding how efficacious the technique is and whether its routine use for topical anesthesia is warranted.

LOCAL ANESTHESIA BY CONVENTIONAL INJECTION

Wittrock and Fischer4 and later Trapp and Davies5 demonstrated that human blood can be readily aspirated with the smaller-gauge needles. Trapp and Davies reported positive aspiration through 23-, 25-, 27-, and 30-gauge needles without a clinically significant difference in resistance to flow. Malamed recommends the use of larger-gauge needles (i.e., 25 gauge) for injection into highly vascular areas or areas where needle deflection through soft tissue may be a factor.6 Regardless of the size of the needle used, it is generally agreed that the anesthetic solution should be injected slowly and that the dentist should watch the patient closely for any evidence of an unexpected reaction.

ANESTHETIZATION OF MANDIBULAR TEETH AND SOFT TISSUE

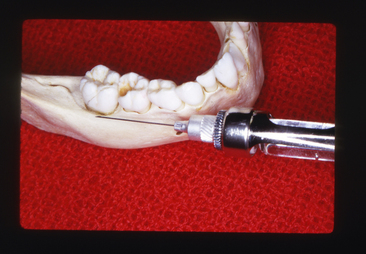

INFERIOR ALVEOLAR NERVE BLOCK (CONVENTIONAL MANDIBULAR BLOCK)

Olsen reported that the mandibular foramen is situated at a level lower than the occlusal plane of the primary teeth of the pediatric patient.7 Therefore the injection must be made slightly lower and more posteriorly than for an adult patient. An accepted technique is one in which the thumb is laid on the occlusal surface of the molars, with the tip of the thumb resting on the internal oblique ridge and the ball of the thumb resting in the retromolar fossa. Firm support during the injection procedure can be given when the ball of the middle finger is resting on the posterior border of the mandible. The barrel of the syringe should be directed on a plane between the two primary molars on the opposite side of the arch. It is advisable to inject a small amount of the solution as soon as the tissue is penetrated and to continue to inject minute quantities as the needle is directed toward the mandibular foramen.

The depth of insertion averages about 15 mm but varies with the size of the mandible and its changing proportions depending on the age of the patient. Approximately 1 mL of the solution should be deposited around the inferior alveolar nerve (Figs. 13-1 and 13-2).

LONG BUCCAL NERVE BLOCK

For the removal of mandibular permanent molars or sometimes for the placement of a rubber dam clamp on these teeth, it is necessary to anesthetize the long buccal nerve. A small quantity of the solution may be deposited in the mucobuccal fold at a point distal and buccal to the indicated tooth (Fig. 13-3).

INFILTRATION ANESTHESIA FOR MANDIBULAR PRIMARY MOLARS

Wright and colleagues have studied the effectiveness of injecting local anesthetic solution in the mucobuccal fold between the roots of primary mandibular molars.8 Based on observational data, little or no pain was experienced by 65% of the children during cavity preparation. It was also noted that children who demonstrate comfort at the time of injection are likely to exhibit no pain during successive procedures.

Oulis and associates9 reported very similar studies comparing the effectiveness of mandibular infiltration anesthesia to mandibular block anesthesia in children 3 to 9 years of age for restorative pulpotomy and extraction therapies in primary mandibular molars. Eighty-nine and 80 children, respectively, were included in their studies. Oulis and associates found that the two anesthesia techniques were equally effective for restorative procedures, but the mandibular infiltration technique was less effective than mandibular block for extraction and pulpotomy.9 In 1976 a new local anesthetic, articaine, was introduced in Europe and by 1983 it was in use in Canada. It was not available in the United States until 2000, by which time the preservative had been removed from the formulation, and it received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Articaine (Septocaine), manufactured by Septodont (http://www.septodontusa.com) underwent several research studies to test reliability and effectiveness, and became readily available and widely used. Articaine is unique among local anesthetics because it contains a thiophene group as well as both ester and amide groups. Articaine is an amide anesthetic (it has an amide intermediate chain) that is metabolized in the liver. The associated ester group also allows plasma metabolism via pseudocholinesterase, which purportedly increases the rate of breakdown and reduces toxicity. This difference in metabolism gives articaine the advantage of having a 30-minute half-life; lidocaine, for example, has a 90-minute half-life.10–14

Sharaf15 demonstrated that behavior in young children can be adversely affected by the painful mandibular block. It is well known that articaine has a high bone penetrating ability, which suggests that it may be more successful as a locally injected infiltration. From these reports, one may infer that mandibular infiltration anesthesia may produce adequate anesthesia in mandibular deciduous molars for most restorative procedures.

MANDIBULAR CONDUCTION ANESTHESIA (GOW-GATES MANDIBULAR BLOCK TECHNIQUE)

In 1973, Gow-Gates introduced a new method of obtaining mandibular anesthesia, which he referred to as mandibular conduction anesthesia.16 This approach uses external anatomic landmarks to align the needle so that anesthetic solution is deposited at the base of the neck of the mandibular condyle. This technique is a nerve block procedure that anesthetizes virtually the entire distribution of the fifth cranial nerve in the mandibular area, including the inferior alveolar, lingual, buccal, mental, incisive, auriculotemporal, and mylohyoid nerves. Thus with a single injection the entire right or left half of the mandibular teeth and soft tissues can be anesthetized, except possibly the mandibular incisors, which may receive partial innervation from the incisive nerves of the opposite side. Gow-Gates suggested that, once the technique is learned properly, it rarely fails to produce good mandibular anesthesia.16 He had used the technique in practice more than 50,000 times. The technique has become increasingly popular and is often referred to as the Gow-Gates technique.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses