13

Head and Neck Cancer

I. Background

Description of Disease/Condition

Head and neck cancers vary by histopathology and location in this region, yet 90% arise from the lining mucosa of the oral cavity and pharynx, also referred to as the upper aerodigestive tract.

This chapter emphasizes the “mucosal” or epithelial-derived squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The majority of non-epithelial-derived tumors in the head and neck region are lymphomas (non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s lymphomas) (see Chapter 8 “Hematological Diseases”). The biology of head and neck SCC (HNSCC) differs from other cancers of the thyroid, skin, brain, eye, and manifestations of lymphomas in the head and neck.

- Nasal—the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, including the sphenoid, frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinus

- Oral cavity—lips, buccal mucosa, gingiva, anterior two-thirds of the tongue, floor of the mouth, retromolar trigone, and hard palate

- Pharynx—a long tubular structure from behind the nose to the region of voice box and esophagus divided into nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx

- Nasopharynx—upper third of pharynx posterior to nasal and superior to oropharynx up to the skull base containing the eustachian tubal apertures in lateral walls

- Oropharynx—base of the tongue, soft palate, uvula, tonsillar area, and posterior pharyngeal wall

- Hypopharynx—the lower third of the pharynx, between the oropharynx and esophagus, including the areas around the upper part of the voice box (pyriform sinuses, post cricoid area of the posterior larynx, and larynx)

- Larynx—the voice box is a short passageway formed by the cartilage just below the pharynx in the neck and includes the epiglottis, which prevents food from entering the air passages

- Lymph nodes—located in the neck, lymph nodes can have cancer spread to them from tumors in the head and neck areas and other regions.

- Major salivary glands—parotid glands, submandibular glands, and sublingual glands. The mouth, lips, palate, and tongue contain multiple minor salivary glands.

| Nasal cavity, vestibule, and paranasal malignancies |

| Epithelial tumors: squamous cell carcinoma, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma) |

| Nonepithelial tumors: mucosal melanoma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcomas, synovial sarcomas, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma |

| Nasopharyngeal malignancies |

| Squamous cell carcinoma, lymphomas, nasopharyngeal carcinoma (keratinizing, nonkeratinizing, and undifferentiated types), fibrosarcoma |

| Oral cavity |

| Epithelial: squamous cell carcinoma, verrucous carcinoma |

| Nonepithelial: striated muscle rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma/Kaposi |

| Oropharynx |

| Squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoepithelialomas, lymphomas |

| Hypopharynx |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Larynx |

| Epithelial: squamous cell carcinoma, verrucous carcinoma |

| Nonepithelial: adult rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Thyroid malignancies and parathyroid malignancies |

| Papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma |

| Salivary gland malignancies |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma |

| Skin |

| Squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, melanomas, angiosarcoma |

| Facial bones |

| Osteosarcoma of the mandible, synovial sarcoma |

Pathogenesis/Etiology

Risk Factors

Tobacco, alcohol use, ultraviolet light, viral infection, radiation, genetic factors, malnourishment, diet, and chemical exposures to betel quid and areca nut are established risk factors for head and neck cancers, with tobacco and alcohol use causing more than 80% worldwide, including the United States (see also Chapter 16, “Substance Use Disorders”).

Tobacco

Tobacco use in any form can cause head and neck tumors, with risk increasing in proportion to the duration and intensity of usage. Patients with head and neck cancer who continue tobacco use carry a high risk for a second primary tumor in the region.

- Cigarette smokers have a cancer incidence six to eight times higher than nonsmokers.

- Cigar, pipe, filtered cigarette, and “beedi” or “bidi” smoking have a dose–response relationship to oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers.

- Smokeless tobacco, chewing tobacco, and snuff use results in an increased risk of invasive tumors arising from premalignant lesions of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa.

- Cancer incidence also has a positive correlation with exposure to the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, and aromatic amines, along with many other carcinogens, found in tobacco smoke.1

- Second-hand tobacco smoke is an environmental hazard, creating risk of head and neck cancers in nonsmokers.

- Cancer risk decreases after 5 years of smoking cessation, and risk is comparable with nonsmokers after 20 years of abstinence.

Alcohol

- Alcohol has been identified as a carcinogenic agent in many cohort studies.2 However, the exact mechanism of carcinogenesis is not well known. Alcohol may promote carcinogenesis by acting as a solvent, that is, enhancing the penetration of carcinogens in oral tissues, or it may act as a cofactor along with tobacco.

- All types of alcohol have been associated with increased risk.

- Certain genetic predispositions and polymorphisms are enhanced by alcohol intake.3

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- HPV is a sexually transmitted virus; oncogenic types 16 and 18 have been found to have a causal role in a subgroup of head and neck invasive tumors of the oropharynx and oral cavity.

- Sites most commonly related to HPV infection are the base of the tongue and tonsils.

HPV-associated head and neck cancers have a different risk profile from non-HPV-associated head and neck tumors—that is, patients are usually young, nonusers of tobacco and alcohol; possess a distinct molecular profile; have a better outcome after complete treatment; and have a lower incidence of second cancers.

Betel Quid

- Betel quid is a mixture of areca nut, slaked lime, and spices rolled in betel leaf. Gutkha and pan masala are variants with tobacco.

- Chewing this mixture is a strong risk factor for cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx in Southeast Asia and immigrants from this region to the United States.

- Oral submucous fibrosis, a premalignant lesion, is also a result of areca consumption.

Ultraviolet Light

- Exposure among outdoor workers is associated with a very high incidence of lip cancers, with SCC most commonly occurring on the lower lip. See Fig. 13.1.

Figure 13.1 Squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip in a 61-year-old white male with a history of cigarette smoking.

Courtesy of Dr. Bert Wood.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

- EBV causes nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Diet

- A diet rich in fruits, vitamin A, zinc, carotene, and tocopherol is protective from HNSCC.

- Nitrite-rich preserved meat consumption increases risk for nasopharyngeal carcinomas.

Other Factors

Also suggested as risks for HNSCC are: heredity; environmental and occupational exposure to formaldehyde, asbestos, wood dust, and industrial pollutants like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons4; radiation exposure from environmental, medical, or occupational reasons; and immunosuppressant medications used after transplant surgery.

Pathogenesis/Progression

The majority of HNSCCs develop from premalignant lesions such as leukoplakia and erythroplakia, which present with histological findings of dysplasia; however, not all dysplastic lesions progress to carcinoma (see Chapter 16, “Substance Use Disorders”). Current research indicates that the development of cancer is driven by an accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes within a clonal population of cells.5

Epidemiology

Incidence

- Head and neck cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide.

- In the United States, approximately 40,000–50,000 people are diagnosed with head and neck cancer each year.6

According to the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data in the United States, there is a marked difference in incidence, tumor site, and outcome between sexes, socioeconomic status, and race after standardization for age.

Mortality

- In the United States, approximately 10,000–11,000 people die from head and neck cancers annually.6

- In the United States, the mortality from oral cavity and oropharynx cancer decreased from 5.1 to 3.8 per 100,000 people in men and from 2 to 1.4 per 100,000 people in women, age adjusted, 1992–2007.

- Worldwide disparities in time of detection, care, and tumor characteristics result in immense differences in mortality. Mortality rates in western Europe and the United States are lower when compared with central and eastern Europe.

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

Therapeutic interventions and prognosis differ widely depending on the stage at diagnosis, location and histology of the tumor. Coordination of care is important before, during, and after cancer therapy due to the extent, nature, severity, and duration of complications of therapy in the head and neck region that can impact esthetics, speaking, mastication, deglutition, overall nutrition, comfort, and quality of life.

II. Medical Management

II. Medical Management

Identification

Head and neck cancers can be asymptomatic until they are quite advanced. They present with insidious symptoms. Expeditious diagnosis and treatment has an impact on cancer outcomes.

- “Sore” in the mouth that bleeds and fails to heal

- White or red patch in the mouth, which cannot be dislodged

- Lump in the tongue, inner cheek of the mouth (buccal mucosa), floor of the mouth

- Difficulty swallowing or pain while swallowing

- Hoarseness or change in voice, difficulty in speech

- Reduced mouth opening, nonarticular pathology

- Blood in sputum

- Mobile or dislodged tooth without any trauma or significant gum disease

- Nasal fullness with bleeding

- Development of double vision (diplopia)

- Sensation loss or radiating pain

- Neck lumps

- Swelling on the upper or lower jaw or under the lower jaw

- Earache or reduced hearing

- Tearing of eyes (epiphora)

- Fracture of jaws without trauma

Visual screening is a simple method for early detection of oral lesions. An American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Screening for Oral SSCs provided evidence-based clinical recommendations.8 The panel emphasized that screening for oral cancer is one component of a thorough hard-tissue and soft-tissue examination that follows patient history and risk assessment and that both benefits and limitations result from screening, with limited evidence that screening impacts oral cancer mortality rates. See Table 13.1.

Table 13.1. Recommendations of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Screening for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas, Based on Evidence (April 2009)

Source: Patton et al.9

Source: Adapted from Rethman et al.8

| Topic | Recommendation |

| Screening during routine examinationsa | The panel suggests that clinicians remain alert for signs of potentially malignant lesions or early-stage cancers in all patients while performing routine visual and tactile examinations, particularly for patients who use tobacco or who are heavyb consumers of alcohol. |

| Follow-up for seemingly innocuous lesions | For seemingly innocuous lesions, the panel suggests that clinicians follow up in 7–14 days to confirm persistence after removing any possible cause to reduce the potential for false-positive screening results. |

| Follow-up for lesions that raise suspicion of cancer and those that are persistent | For lesions that raise suspicion of cancer or for lesions that persist after removal of a possible cause, the panel suggests that clinicians communicate the potential benefits and risks of early diagnosis. |

Considerations include the following:

|

|

| Use of lesion assessment devices | Although transepithelial cytology has validity in identifying disaggregated dysplastic cells, the panel suggests surgical biopsy for definitive diagnosis. |

a There is insufficient evidence that use of commercial devices for lesion detection that are based on autofluorescence or tissue reflectance enhance visual detection of potentially malignant lesions beyond a conventional visual and tactile examination.

b Heavy alcohol consumption is defined as follows: for men, consumption of an average of more than two drinks per day; for women, consumption of an average of more than one drink per day. Sources: Pelucchi et al.10 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.11

Adjunctive Screening Tests

Aids to oral, oropharyngeal cancer, and precancerous lesion screening are not widely used due to the lack of randomized controlled trials or large-scale studies that are sufficiently sensitive and specific in comparison to the gold standard of biopsy results to demonstrate effectiveness and general lack of assessment in populations seen in general dental practices.9 Another disadvantage is their inability to differentiate cancer from precancerous lesions.12

Medical History/Physical Examination

A detailed patient history of symptoms, risk factors, environmental or occupational exposures including tobacco and alcohol use, medical and surgical history, and family history is obtained and recorded prior to physical examination.

Components of the physical examination for the head and neck cancer patient include the following:

- Inspection of the skin and scalp for nodules, ulcers, and pigmented areas.

- Neurological exam of all cranial nerves for sensory and motor function of the eye, face, jaws, ears, swallowing, shoulder, and tongue.

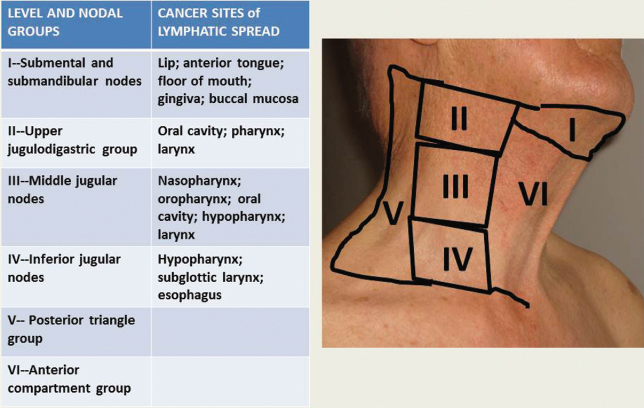

- Extraoral examination for lymph nodes, nodules or masses, thyroid size and mobility, symmetry, consistency, and tenderness. Any decrease in jaw opening, loss of sensation, motor function, swallowing difficulty, or bony architecture changes and lip consistency are noted. Areas around the ears are examined for tenderness, nodularity, and asymmetry. Malignant lymph node enlargements tend to be nonpainful and nontender to palpation, hard and indurated on palpation, and fixed to underlying muscle and tissues compared with inflammatory and infectious lymph nodes that may be painful, tender, and rubbery to palpation and mobile in all directions. Typical head and neck lymphatic drainage patterns can give an indication of possible location of tumors. See Fig. 13.2.

- Intraoral examination with bimanual palpation of cheeks, tongue, and floor of the mouth. A mouth mirror-assisted exam is made of all regions of the mouth, tonsillar area, and hard and soft palate.

- Indirect laryngoscopy is carried out with a mirror to visualize tongue base, nasopharynx, epiglottis, and true and false vocal cords with surrounding wall mucosa.

- Nasal flexible endoscopy involves applying a local anesthetic spray, and then using a flexible endoscopy for visualization of nasal cavity, nasopharynx, soft palate movement, pooling of secretions, ulcerations, erythema, and papillary projections. Asymmetry is recorded.

- Triple endoscopy examination under anesthesia. Head and neck tumors may be synchronous with primary SCC in the esophagus, lower airway, and the lungs. Thus, laryngoscope, bronchoscope, and esophagoscope examinations may be used to visualize and allow biopsy under anesthesia, particularly when the primary tumor location is unknown and metastatic neck nodes are the presenting sign.

Figure 13.2 Neck node levels and head and neck cancer lymphatic drainage patterns.

Laboratory Testing

There are no mandated laboratory tests in the diagnosis of an HNSCC. However, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy may require a complete blood count with white cell differential; basic metabolic, r/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses