Chapter 13

Cosmetic Blepharoplasty

Introduction

Simply put, youth is characterized by fullness and volume, while hollowness and deflation reveals age. While this generalization has not always been appreciated, it has become a mantra of facial rejuvenation over the last decade. Even though the amount of periorbital volume loss and decreased skin elasticity is unique to each patient, the complaints are often the same. Patients are often unhappy with excess eyelid skin and temporal hooding that lead to tired, sad, heavy-looking eyes, and difficulty wearing makeup for female patients. These changes can sometimes interfere with vision and activities of daily living and recreation. In the lower lids, patients comment on bags, bulges, and loose skin.

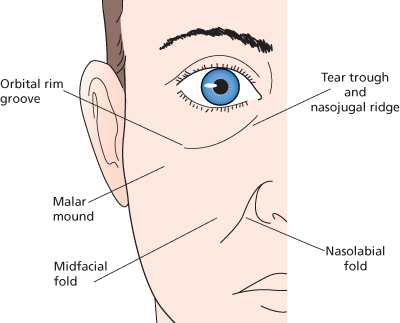

Old photographs remind patients of how they used to be, and can be a revealing starting point for discussing surgical options for both periorbital rejuvenation and improvement. This chapter discusses our approach to the blepharoplasty patient and surgical techniques that aim to address periorbital aging changes, restore each individual’s youthful appearance, and minimize complications (Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1 Idealized patient showing classic aging changes and then following surgical rejuvenation.

Anatomy

Knowledge of eyelid anatomy is fundamental in lid surgery. In addition to contributing to facial expression, eyelids are dynamic structures that protect the globes, tear film integrity of the cornea, and provide an aperture for vision. The upper eyelid is the sight saver. Thus, blinking alone maintains the tear film, corneal clarity, and thereby good vision. The shape of the palpebral fissure and its position relative to the globe determines how the eye “looks.” The distance between the eyelid margins is typically 28–30 mm horizontally and 10–12 mm vertically in the occidental eye, and less so in Asian eyelids. The eyelid skin is the thinnest in the body, with loose connective tissue usually devoid of fat. This allows for the formation of fine wrinkles with age and further thinning from repetitive rubbing or stretching.

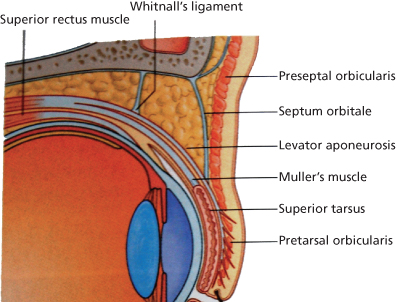

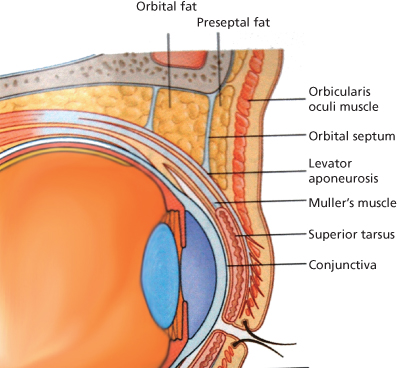

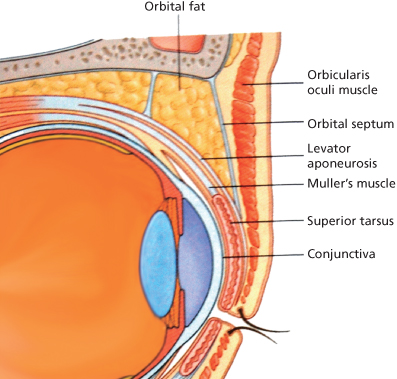

The main protractor of the eye is the orbicularis muscle. It is divided into orbital, preseptal, and pretarsal portions. The main upper lid retractors are Muller’s muscle and levator palpebrae superioris. The levator originates at the orbital apex and travels anteriorly until its aponeurosis inserts widely onto the anterior surface of the tarsus along with the elastic fiber network, (EFN), with fibers that extend to pretarsal orbicularis and skin. These fibers (EFN) help create the eyelid crease1 (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2 Sagittal section of the upper eyelid. Notice the fibers extending from the levator aponeurosis through the orbicularis muscle to insert onto the pretarsal dermis. These fibers are crucial to forming the eyelid crease.

Directly beneath and attached to the levator is Muller’s muscle. It arises from the undersurface of the levator, inserts onto the superior tarsal border, and accounts for approximately 2 mm of lid elevation. Posterior to Muller’s muscle is conjunctiva and adnexal structures for tear and mucous production.

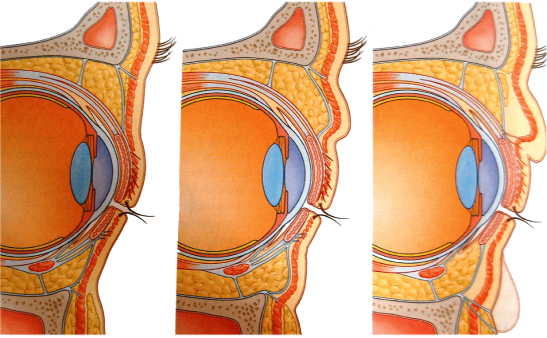

The orbital septum separates the eyelid from the orbit. The septum originates at the arcus marginalis of the frontal bone at the superior orbital rim. It fuses with the levator aponeurosis a few millimeters above the primary eyelid crease. This combined fascia of aponeurosis and septum forms an envelope that contains the preaponeurotic fat. A lower fascial envelope insertion results in a fuller lid, as seen in Asian eyelids. The septum must be opened to reach the two upper lid fat pockets. The levator is located beneath the fat. Thus, identification of the preaponeurotic fat is a constant and critical landmark for identifying and protecting the levator.

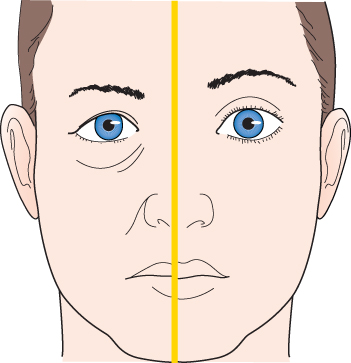

The position, shape, and presence of the upper eyelid crease are critically important in the aesthetically pleasing eyelid. Thus, reforming it is critical for a successful ptosis or blepharoplasty procedure. The crease is formed from levator fibers and EFN that extend anteriorly, through the orbicularis muscle, and insert onto the dermis of the eyelid skin as far down as in the lashes. It is only 2 mm above this interdigitation where the orbital septum fuses with the aponeurosis forming the previously mentioned fascial envelope. The height of this envelope and the crease formation is the main difference between Asian and occidental eyelid appearances (Figures 13.3 and 13.4), thereby giving us the variation of eyelid crease height in all human beings. Through proper surgical technique, it is possible to enhance the eyelid crease in blepharoplasty or ptosis surgery, as well as to reconstruct a crease in congenital ptosis or following trauma. It is also the technique of re-creating a little higher eyelid crease in an Asian individual and still keeping the physiognomy of the facial features in proportion.

Figure 13.3 and 13.4 A comparison of a Caucasian and Asian upper eyelid without a crease. Note the higher attachment of the orbital septum, and therefore a higher location of the fascial envelope in the Caucasian lid. In addition, because of the lower fascial envelope in the Asian lid, the aponeurotic fibers are unable to extend and insert into the dermis. This gives the Asian eyelid a low, absent, or poorly defined eyelid crease.

The skin above the crease is typically loose and nonadherent to allow for lid movement. This comparatively lax skin hangs over the crease creating the eyelid fold. With age, the eyelid crease may become elevated as with acquired blepharoptosis, that is, the Bette Davis look or the “bedroom eye” look. The tight compartmentalization of the preaponeurotic fat pads between the orbital septum and levator aponeurosis retract into the orbit. The result is a deep superior sulcus. This is further exacerbated in patients with blepharoptosis who raise their brows in order to hold their eyelids up for seeing, as in the Bette Davis look (Figure 13.5).

Figure 13.5 Marilyn Monroe exemplifies the classic bedroom eyes look.

(Image from KY Olson, Creative Commons Attribution, www.flickr.com)

Therefore, the loss of orbicularis tone and elasticity that results in weakened suspensory structures leads to these upper periorbital and eyelid changes. Traditional blepharoplasty techniques of generous excision of skin, orbicularis, and fat further distorted these tissue relationships and perpetuated a high crease and hollow sulcus or cachectic look. Current surgical practice aims to restore youthful tissue volume and re-create a fuller upper periorbital region.2

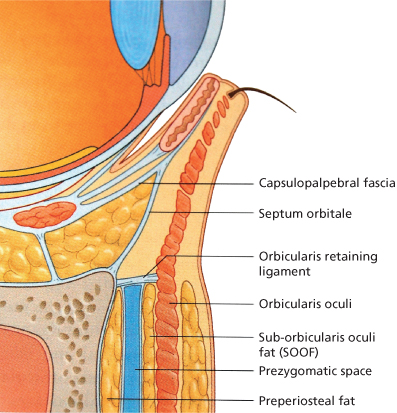

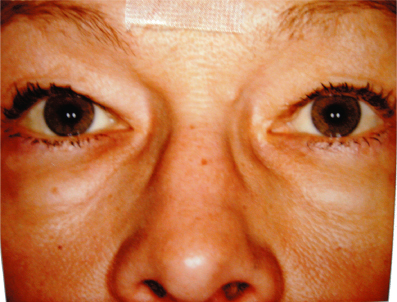

The lower eyelid is analogous to the upper lid. Simply, it can be divided into three layers. The anterior lamella includes the skin and orbicularis muscle and the septum. The middle lamella consists of the three orbital fat pockets and retractors, mainly the capsulopalpebral fascia and the inferior tarsal muscle. The conjunctiva and tarsus make up the posterior lamella. The most common characteristics of lower periorbital aging—crepey lower lid skin, lower eyelid bags, lower lid laxity, and a pronounced nasojugal groove (tear trough)—can be explained by lower eyelid anatomy (Figure 13.6).

Figure 13.6 Lower eyelid anatomy. Note the orbitomalar ligament (orbicularis retaining ligament), which spans from the orbital rim periosteum to the orbicularis muscle. This coincides with the palpebromalar groove that appears with aging. Strengthening and resuspending this ligament is important in lower eyelid blepharoplasty.

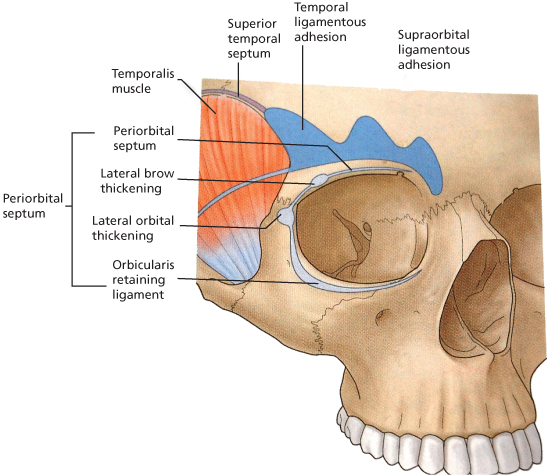

At the lower lid cheek junction medially, the orbicularis muscle is directly attached to the bony orbital rim. This tight connection creates the nasojugal groove. Laterally, the orbicularis muscle is indirectly attached to the orbital rim via fibrous tissue called the orbicularis retaining ligament or orbitomalar ligament.3 In the lateral canthal area, the orbicularis retaining ligament is continuous with the lateral orbital thickening. This thickening is a dense fascial condensation over the lateral orbital rim and superficial to the lateral canthal tendon.4 Deep to the orbital thickening are the skeletal attachments of the upper and lower lid tarsal plates with reinforcement bands from the levator aponeurosis above and Lockwood’s ligament below. All of these fascial structures and pretarsal orbicularis converge and attach to the internal portion of the lateral orbital rim at Whitnall’s tubercle. In addition, the more superficial preseptal orbicularis fibers from the upper and lower lid interdigitate in the lateral canthal area to form the lateral canthal raphe. With time and use, these retaining ligaments along with the septum are weakened and the orbicularis muscle loses tone, allowing the lower lid orbital fat to bulge forward (Figures 13.7–13.11).

Figure 13.7 Periorbital retaining ligaments. With aging, these ligaments appear as grooves and concavities, while the overlying tissue forms mounds and bulges.

Figure 13.8 A surface anatomy drawing showing the bulges and grooves apparent with age due to the underlying ligamentous attachments.

Figure 13.11 Cross section showing possible eyelid soft tissue changes due to attenuation of ligamentous attachments.

Orbital fat in the lower lid is traditionally divided into three compartments. The nasal and central pockets are separated by the inferior oblique muscle. The central and lateral pockets are divided by the arcuate expansion of the capsulopalpebral fascia. Outside of the orbital rim in the upper malar area lies the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF), which can be repositioned in periorbital rejuvenation procedures.

Evaluation and Considerations

As we learned in medical school, every patient encounter begins with a thorough history and involves listening to the patient. This is especially important in the plastic surgery arena. While it may sometimes appear obvious why a patient is seeking plastic surgery consultation, it is imperative to elicit which of their characteristics bothers them the most. Their “chief complaint” may be subtle and surprising. It needs to be addressed along with each patient’s periorbital rejuvenation plan. In addition to the past medical history and adverse medication reactions, a history of prior ocular surgery needs to be obtained. This is true whether or not the patient was satisfied with their previous results. Such information may provide insight into the patient’s expectations, and may help put the patient and surgeon “on the same page” when discussing realistic outcomes.

Past ocular history is also important. Specifics such as dry eye symptoms of burning, irritation, pain, contact lens wear and/or intolerance, and artificial tear usage are essential. Prior LASIK (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis) or related corneal refractive surgery patients are at high risk of worsening or developing dry eye symptoms following upper eyelid surgery. The procedure itself should not cause dry eye unless there is lagophthalmus.

In our office, the physical exam begins with simple observation. Photographs are taken of the whole face, the periorbital area straight on and at oblique and lateral views. Objective measurements are taken. The MRD1, palpebral fissure height, and levator function are recorded. The MRD1 in downgaze is measured in cases of ptosis. In cases of asymmetric ptosis, Hering’s law of equal innervation is evaluated by holding one lid up and allowing the opposite lid to drop to its true level. This is also documented with photos. The presence and quality of a Bell’s reflex and orbicularis tone are assessed, as these are normal eye protective mechanisms.

A slit-lamp exam is performed on all patients. Everting the upper lids is very useful to evaluate the potential for dry eye. Attention is paid to the lashes, the height and quality of the tear film, conjunctival inflammation, including giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC), allergic follicular changes, corneal staining, and evidence of prior ocular surgery. While much is made of Schirmer testing as the only available objective, but not always reproducible, method of measuring tear production, we feel that slit-lamp exam, patient history, and preoperative counseling are the most effective ways to prevent postoperative dry eye disappointment and surprises.

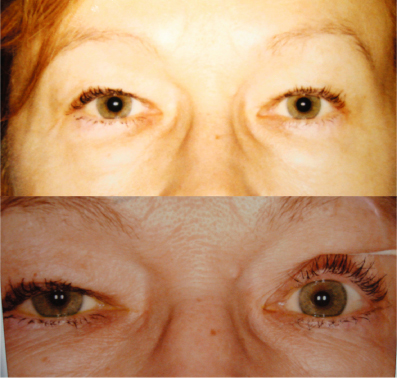

Phenylephrine testing is often included in the preoperative evaluation in both patients with obvious and severe ptosis and in those with a more subtle droop. Phenylephrine 2.5% or 10% stimulates Muller’s muscle and raises the eyelid. It shows patients what their eyes would look like in a more open position, it may reveal increased dermatochalasis with a higher lid position, and gives the patient and surgeon an idea of the eyebrow position when in a relaxed state. Photos are taken after the drops are administered (Figures 13.12 and 13.13).

Figure 13.12 A preoperative photo showing elevated brows indicating subtle ptosis. Manual elevation of the left upper lid reveals the true lid height, illustrating Hering’s law.

Figure 13.13 The same patient following bilateral phenylephrine drops. Notice the improved upper lid height and more relaxed brows.

Visual field testing is also performed on certain patients to confirm whether or not the ptosis, brow ptosis, and/or dermatochalasis are causing visual field loss. These tests are usually manually conducted. The patient is first tested with their lids in their natural position. The test is repeated with their lids taped up. These tests reveal the amount of visual field loss due to eyelid malposition and how much visual improvement the patient may expect following surgery.

Finally, but most importantly, complications and precautions are discussed. A second review of patient medications is done. Patients are asked specifically about blood thinners, including aspirin products, multivitamins, and herbal supplements. They are asked to stop using these products, often in conjunction with the approval of the prescribing physician, prior to surgery. The risk of bleeding and possible vision loss is discussed with each patient (Figure 13.14).

Figure 13.14 A patient with a retrobulbar hemorrhage. The orbit is firm, and the eyelid cannot be opened manually.

In order to decrease this risk further, we require all patients to use frozen compresses continuously for the first 48 hours after surgery reclined in bed or in a chair. Having the patient’s head slightly inclined backward, rather than upright or in a 45-degree angle, reduces the lower lid edema and collection of ecchymosis. They are instructed to limit their activity to walking to the restroom and eating during this period (Figure 13.15).

Figure 13.15 Recovery room frozen peas.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses