12

The Anatomy of Failure

Age

Abnormal morphology of the impacted and adjacent teeth

Ankylosis and invasive cervical resorption

Wildly ectopic teeth

Incorrect positional diagnosis

Surgical exposure without prior orthodontic planning

Resorption of the root of an adjacent tooth

Poor anchorage

Inefficient appliances

Expert opinion and second opinions during treatment

There are many factors complicating the treatment of impacted teeth that are not present in routine general orthodontics. In the first place, the affected tooth is not visible, and is only imaged using clinical and radiographic aids. It thus cannot be examined for abnormality in the same manner or with the same degree of thoroughness as a normally erupted tooth. The precise, three-dimensional location of a normally erupted tooth is obvious from a clinical examination. So too is its degree of rotation, the orientation of its long axis and its relation to the erupted adjacent teeth, as well as minor flaws in the morphological features of its crown, surface imperfections in the smooth outline or colour of the enamel. Exactly what types of corrective movement its orthodontic treatment will demand can be seen by direct vision, and biomechanical planning is straightforward. These luxuries are not available when dealing with an impacted tooth.

One of the most constant features of the normal growing child is the natural and spontaneous eruption of teeth. In the deciduous dentition, this occurs between the ages of 6 months to 2.5 years and these teeth shed normally between 6 and 10 years later, to be replaced within just a few months and in rapid succession by the permanent teeth. This innate attribute is so universal that a single tooth failing to erupt, when all other factors are apparently favourable, should raise the suspicions of the discerning orthodontist. The very fact of its non-eruption raises questions as to why this should be, and the answers range from the common and the obvious to the unusual and least expected.

Determining aetiology must not be looked on as a mere theoretical exercise, but rather an essential prerequisite that provides the basis for the treatment plan for each individual case. Perhaps the tooth is quite normal, but there is some local impediment blocking its path (Figures 12.1 and 12.2), or perhaps the location of the tooth germ is ectopic. Alternatively, the cause may lie in a local abnormality of the tooth follicle itself, or perhaps the patient suffers from a general pathological condition that, among other features, adversely affects tooth eruption. Accurate positional diagnosis is often fraught with difficulty and mistakes may be made in locating the tooth – even by experts [1, 2]. As the result, a tooth in an intractable position may be thought to have a good treatment prognosis, and an inappropriate, ill-advised and ill-fated course of treatment will be prescribed.

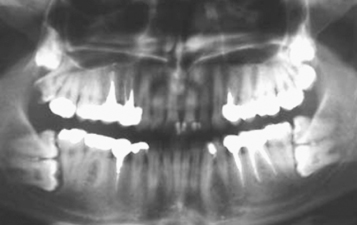

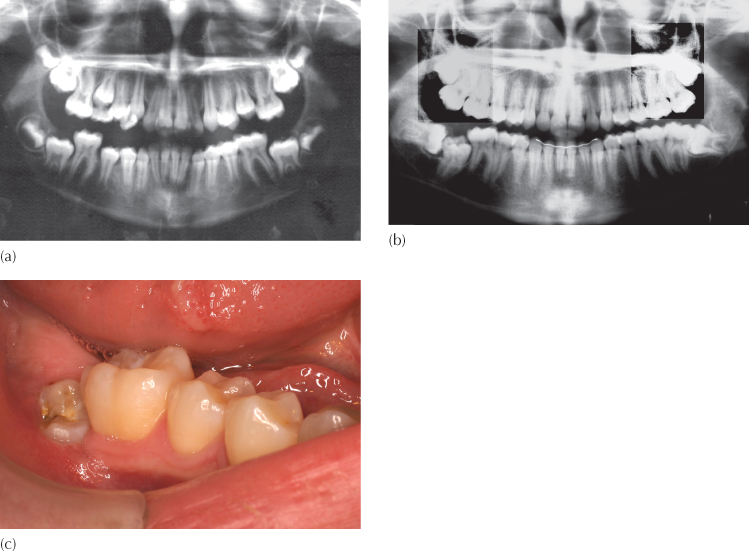

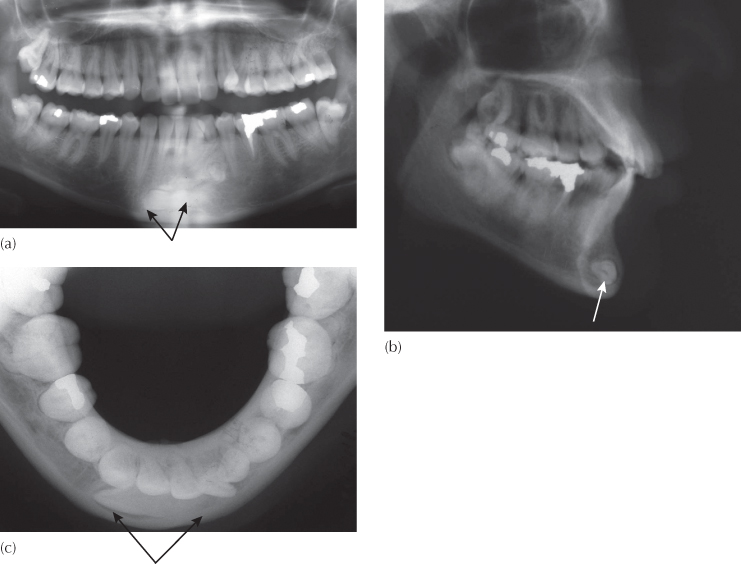

Fig. 12.1 (a) A pre-treatment panoramic view of a patient whose mandibular right second molar had not erupted at the completion of treatment. (b) A panoramic view of the same patient seven years later and five years after the completion of the treatment shows the mandibular right second molar impacted between the two adjacent molars. (c) A month after the surgical removal of the unerupted third molar and exposure of the impacted second molar, the second molar is erupting spontaneously. The impaction is due to the obstruction created by the distal anatomy of the first molar and the large and horizontal third molar.

In many cases all that may be required is for space to be made and this will sometimes reawaken dormant eruptive movements in the tooth, which may then respond by improving its position and even open the window of opportunity to its spontaneous eruption, with the passage of time [3] (see Figure 6.21). At the other end of the scale, a complicated directional traction strategy may be needed to bring the tooth into its place in the arch, while avoiding the roots of adjacent teeth. This we have seen in Chapters 6 and 7 in relation to maxillary canines which are located mesial to the root of adjacent incisors or where the tooth is associated with the resorption of those roots.

An open surgical exposure of the impacted tooth may close over in the succeeding days and weeks and make later attachment bonding unreliable or impossible to achieve. When bonding is performed by the surgeon as an integral task during an open or closed exposure, an attachment may be placed in an inappropriate position on the tooth surface or the pigtail ligature wire or gold chain may have been drawn through the tissues in the wrong direction for traction to resolve the impaction. Alternatively, the bond may fail and, without further surgery, suitable conditions for rebonding may be limited or unattainable (see Figure 8.10).

We have seen in the preceding chapters that the successful outcome of treatment of a difficult impaction, from the orthodontic and surgical points of view, may founder in the long term because of a lack of periodontal support of the treated tooth – a situation that could have turned out very differently had certain precautions been taken in diagnosis, treatment planning, surgical exposure or biomechanics. From the foregoing, we come to appreciate that there are many different areas where opinions regarding attitudes to treatment and where levels of expertise may vary among the three principal specialists involved with the treatment: orthodontist, oral radiologist, oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Taken from the standpoint of how to serve the best interests of our patients, it helps us to understand that communication and rapport between these specialists is of paramount importance. Given the broad spectrum of concerns that are so intimately bound up with the whole approach to this relatively limited phenomenon, it should not be surprising that the chances of error are legion, and with them the distinct likelihood of embarrassing failure. The purpose of the present chapter, therefore, is to analyse the possible causes of failure that occur from time to time in clinical practice and to group them in relation to the various aspects involved in each scenario.

In a recently published study [4], the Jerusalem group collected a sample of 28 young patients for whom treatment for the resolution of their impacted canines had failed. These patients had been referred to the authors by a large number of different orthodontists individually and over a period of several years, with the intention and in the hope that the cases could be salvaged. These 28 patients had 37 failed canines in total and had been in treatment for an average of 26 months for the sample, with a range of 7−72 months, before being referred and, for 10 of these canines, surgical exposure had been performed three times! The referring orthodontists were questioned as to why they thought the case had failed and a large majority had assumed it to be due to ankylosis, while most of the others had missed diagnosing root resorption of the adjacent teeth. A few had blamed bond failure, an intractable location of the tooth and failure to adequately surgically expose the impacted tooth.

These cases were then re-evaluated, many with the help of a CBCT examination and re-treated in accordance with the new findings. The outcome saw 28 of the original 37 failed teeth successfully aligned in the dental arch. Of the remaining cases, two individuals had refused the revised treatment. Of the seven canines with confirmed ankylosis, three were successfully realigned following surgical luxation.

In their conclusions, the authors of this study noted that there are many aspects and minutiae in the treatment of impacted maxillary canine that may cause the treatment to founder. They specifically had the following comments to make:

1. Diagnosis of the location of the tooth and its immediate relationship with the roots of the adjacent teeth is generally treated with cavalier and often negligent simplicity, even though modern technology has provided the tools to achieve this with great accuracy in all three dimensions.

2. With inappropriate positional diagnosis, it follows that traction will be applied in the wrong direction.

3. A lack of appreciation of the considerable anchorage requirements of the case and the need to exploit all available means of enhancing them will inevitably lead to inefficient mechano-therapy and unnecessarily longer treatment.

4. Ankylosis might have afflicted the impacted tooth either a priori or as the result of the earlier surgical or orthodontic manoeuvres.

Age

In Chapter 6, we referred to the fact that the chances for orthodontic traction having a positive effect on an impacted tooth are extremely high in the young patient, but that with advancing age, notably in the over-thirties, the risk of non-movement becomes quite significant [5]. By contrast, the compliance factor among adults undergoing orthodontic treatment towards the relatively undemanding tasks which are in the patient’s realm of responsibility within the treatment protocol (i.e. maintaining a high level of oral hygiene, attending pre-arranged treatment visits, taking proper care of the appliances, placing elastics), is usually considerably better. Thus, while tissue response to orthodontic forces in the child is very positive, the endeavour may be more likely to founder due to a lack of compliance.

In the adult, the ravages of time will often be evidenced by a loss of attachment and bone support, which have been due to large measure by chronic inflammation. But once these factors have been brought under control by appropriate periodontal treatment, routine orthodontic treatment may be recommended with considerable confidence and with a high degree of predictability. But this is true only in regard to the root of a tooth. For the unerupted crown of the tooth this situation may be quite different, since the dental follicle undergoes deterioration in time and direct contact between tooth enamel and the encroaching bony tissues may occur, which will effectively eliminate the orthodontic therapeutic option. Since this phenomenon is age-related, it will rarely be encountered in the young patient, but must be a factor to be considered in planning the treatment of an adult, particularly in the over-thirties age group.

Abnormal Morphology of the Impacted and Adjacent Teeth

Unusually large or small teeth and abnormalities of crown form or root configuration, regardless of their cause, are findings which may affect the decision whether or not to attempt to bring the tooth into the arch. Uncomplicated abnormal morphology presents no impediment to orthodontic movement, since the roots of the teeth are generally invested with normal periodontal tissues and their crowns protected within a normal follicle in which they developed, however abnormally. The unusual form of the teeth may affect the position of the centre of rotation and the centre of resistance, which in turn may affect the direction that orthodontic traction will need to be applied. However, the teeth will respond. In many of these cases, as discussed in Chapter 5 with reference to dilacerate incisors, the orthodontic/surgical modality of treatment may provide an optimal result in aligning these abnormal teeth and in carrying the young patient through the years of childhood and adolescent growth, during which time prosthetic/implant substitution is generally contraindicated. Minor artificial modifications in crown or root form may be necessary during this time but, with this treatment modality, the child is free of iatrogenic, periodontal disease-producing or caries-generating prosthetic devices, when the dentition is at its most vulnerable. At least as important, alveolar bone in the area proliferates quite normally with the resolution of the impaction and maintains its height throughout growth, in parallel with the other teeth. It would be a serious mistake to indiscriminately extract these teeth simply because of a diagnosis of morphological abnormality, and the practitioner is strongly advised to consider all the alternatives before recommending extraction.

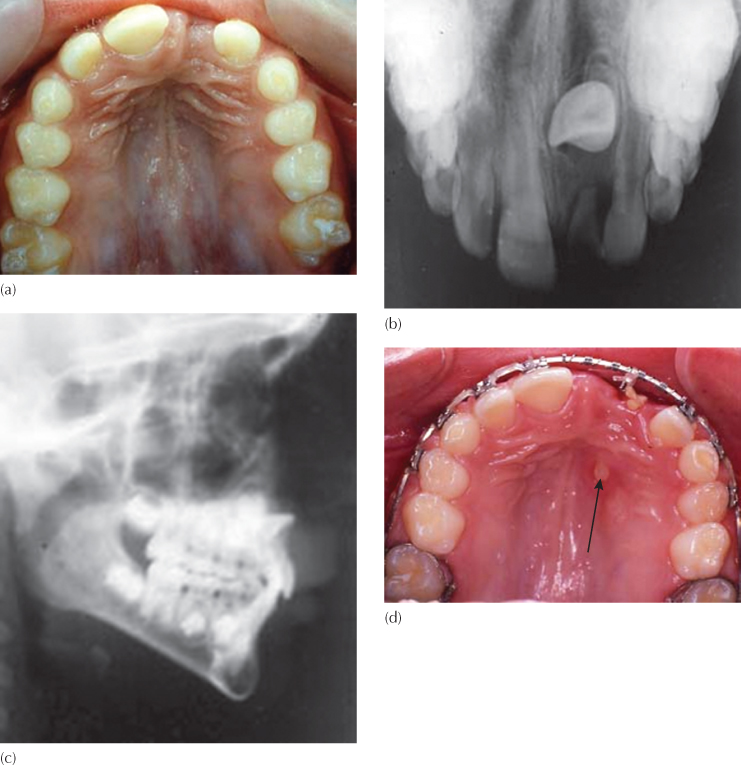

Fixed bridges and implants have a limited life expectancy, and failure may occur much earlier in some instances. This, together with the atrophy of alveolar bone in the immediate area, which inevitably occurs following an extraction, must be considered to be a failure to utilize naturally occurring and available raw material (i.e. the imperfectly formed tooth). Nevertheless, there are cases in which the location of the dilacerations and the degree of the tooth’s distortion leave little option but extraction (Figure 12.3).

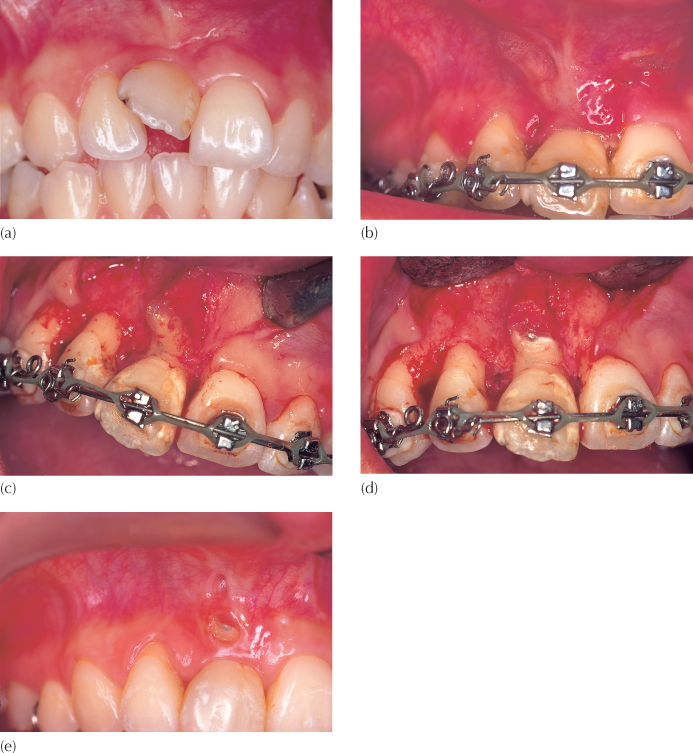

Fig. 12.3 A 15-year-old female presented with a dilacerate but erupted right maxillary central incisor. (a) The initial malalignment. (b) Following alignment and levelling, the root apex can be seen to be pointing labially under a thin cover of overlying oral mucosa. (c) When the flap was raised over the area, with the view to perform an apicoectomy, it was seen that there was no labial bone covering the short and malformed root. (d) The root apex was trimmed back and a retrograde filling placed. (e) At the two-month follow-up visit, the root apex had fenestrated the oral mucosa and the tooth was extracted.

Rather than the canine itself being the cause of the problem, it may occasionally occur that the root morphology of the first premolar is the hidden impediment. The adjacent first premolar normally erupts before the canine and has a buccal and a palatal root, which may sometimes be fused. These roots, particularly the palatal one, may develop in the direct eruption path of the canine which may happen when the premolar erupts with a distal crown tip or when the tooth is rotated mesio-buccally. The root itself may be deformed and exhibit a mesially directed dilaceration of its root apex, as has been described in Chapter 6 (Fig. 6.1c, d). In plane film radiography, the individual roots of the premolar are sometimes not possible to distinguish and superimposition on the canine leaves the bucco-lingual interrelation of the two teeth difficult to ascertain. CBCT imaging of these cases will often clarify the problem and permit the determination of a suitable direction for the application of traction to resolve it. In the case illustrated in Figure 6.1, the root orientation of the premolar must be over-uprighted in a distal direction and then the tooth should be rotated mesio-palatally to free the canine from interference. Once the canine has been brought into alignment, the first premolar may then be re-uprighted and re-rotated into a more optimal position, having due care to avoid a clash of roots in the final analysis.

Ankylosis and Invasive Cervical Resorption

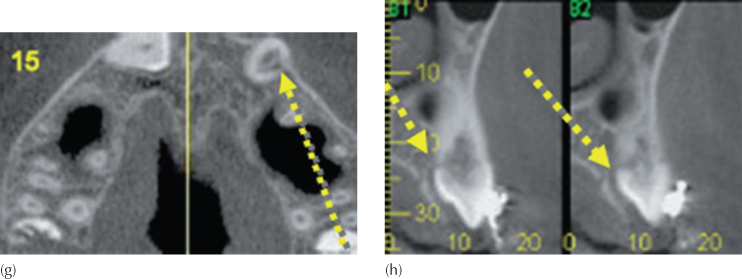

These two phenomena are difficult to diagnose in their early stages, even with good radiographic technique. The presence of either will result in failure of the affected tooth to respond to the applied orthodontic force because of a loss of integrity of the normal periodontal tissue in one or more, often very small, locations on the root surface (Figures 12.4–12.7). This has been discussed fully in Chapter 7 (Figures 7.11–7.13).

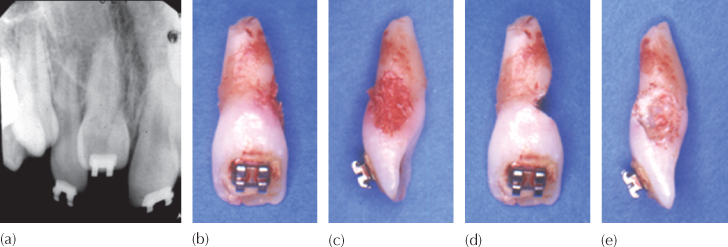

Fig. 12.4 Invasive cervical resorption. (a) The orthodontic attempt to erupt the left central incisor had failed and the tooth was extracted. A close look at the distal side of the cervical area of the tooth shows a defective outline. (b, c) A large area of inflammatory soft tissue in the cervical area of the extracted tooth on the distal side. (d, e) With the soft tissue removed with a scaler, the full extent of the erosive lesion can be seen.

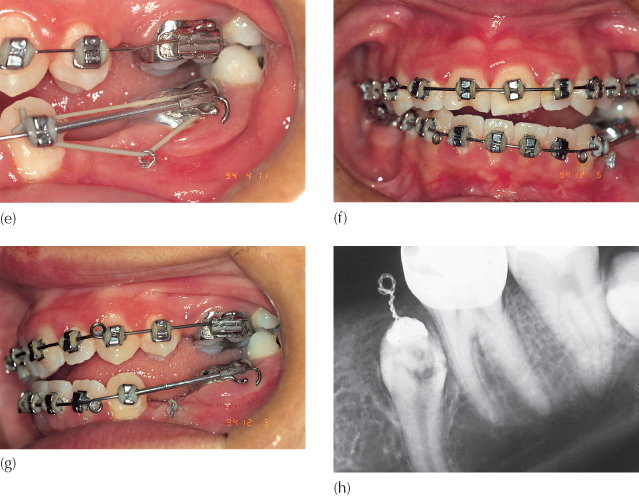

Fig. 12.5 Invasive cervical resorption. (a) A panoramic view shows a deeply situated mandibular left second premolar, which had not responded to extraction of the adjacent first premolar. (b) The treatment plan involved the extraction of a premolar in each of the other quadrants and placement of a fixed appliance. (c) The premolar was exposed and an attachment bonded. Traction was applied immediately. (d) The left side, seen one month post-surgery. (e) Despite the application of light forces, the impacted tooth did not respond and the adjacent teeth had intruded. (f, g) These light forces, over a long period, had generated a left-side open bite and a strong cant of the occlusal plane. (h) A new periapical view at this stage showed a radiolucent area within the crown of the tooth, which turned out to be advanced invasive cervical resorption on the lingual side, which was not seen at the time of surgery, although it was obvious on the original panoramic view and had been overlooked! The original location of the premolar, with its developing apex on the lower border of the mandible and with no obstruction superiorly, had raised the suspicion of the author at the outset.

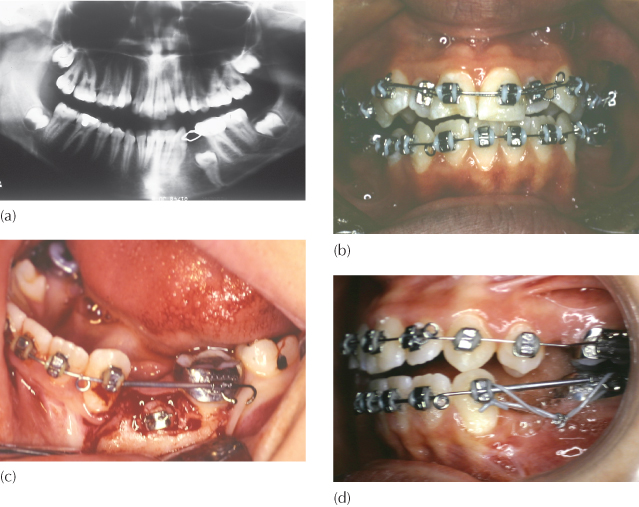

Fig. 12.6 This patient was seen by the oral surgeon and referred for an orthodontic opinion as to which tooth should be extracted. The surgeon suggested the following options: (a) to extract the third molar, expose the first and second molars, drain the cyst, and leave the remainder to the orthodontist; (b) to extract the second molar, together with cyst enucleation, and to free the first molar to erupt; or (c) to extract the first molar, curette the cyst lining, and then upright the second and third molars. Are all these equal possibilities? The missing element is the diagnosis. The first molar was infra-occluded due to invasive cervical resorption (arrow) and must therefore be the tooth to be sacrificed, together with defusing of the cyst. The possibility of pathologic fracture of the mandible was known and accepted, and the molar therefore removed piecemeal. Enucleation of the cyst was impossible, due to poor access and the danger of damaging the second molar – it was marsupialized. An attachment was placed on the second molar and occlusally directed traction was applied from a zygomatic arch implant.

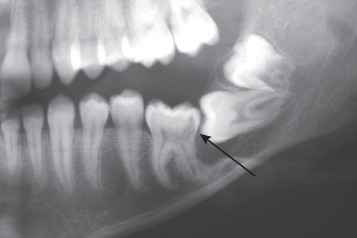

Fig. 12.7 Patient seen by the author in consultation, three years after surgical exposure and failure to resolve the bilateral canine impaction.

(a) Intra-oral view at consultation: patient complaining of an open bite.

(b) Intra-oral view from the initial treatment records, five years earlier.

(c) Anterior section of panoramic view taken prior to surgical exposure showing canines with no apparent pathological involvement.

(d) Periapical view taken at time of consultation visit shows aggressive cervical root resorption on the distal aspect of the root of the left canine.

(e) A buccal three-dimensional view from the CBCT series shows the lesion extending from the distal to lingual sides of the root.

(f) A lingual three-dimensional view from the CBCT series shows the lesion extending from the distal to lingual sides of the root.

(g) A single axial (horizontal) slice from the CBCT to show the right canine lying horizontally above the roots of the incisors. The cross-section of the left canine shows a distinct break in the continuity of the root on the distal side. It is possible to discern the narrow pulp chamber outlined by more radiolucent predentine and the resorbed area of root around it.

(h) Two transaxial (vertical) slices from the CBCT show the palatal point of entry of the resorption process and its mushrooming extension inwards.

Wildly Ectopic Teeth

Although wildly ectopic teeth are seen extremely rarely, there would appear to be few limitations on where teeth may be found in the tooth-bearing areas and beyond, in remote areas of the jaws generally. Several of these are worth exhibiting here, for curiosity value only (Figures 12.8–12.12). Satisfactory imaging of many of these teeth may be achieved with the use of straightforward plane film radiography because of the wide separation of these teeth from the remainder of the dentition. There may be little or no added value in the use of CBCT in many of these cases. As with teeth of abnormal form, their surrounding tissues are generally quite normal and the potential that they may have for responding to the application of orthodontic forces may be excellent. Nevertheless, the question that needs to be answered is whether the estimated length of time involved in their treatment and the periodontal prognosis of the outcome are sufficiently favourable to make the orthodontic/surgical modality superior to other therapeutic options. The answer will usually lean towards extraction or, occasionally, towards leaving the tooth untreated because of difficulty and possible complications in extraction.

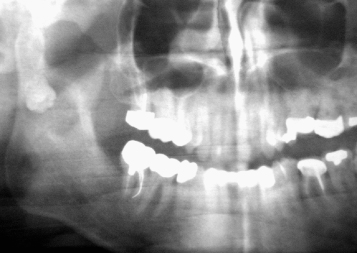

Fig. 12.9 (a–c) Panoramic, lateral cephalometric, and occlusal views of a mandibular left impacted canine crossing the midline and exactly at right-angles to the mid-palatal and antero-posterior planes (arrows). The direction of the X-ray for the cephalogram is in the long axis of the tooth and depicts it in cross-section.

Fig. 12.12 An ‘eye-for-an-eye’ tooth.

(Courtesy of Dr M. King.)

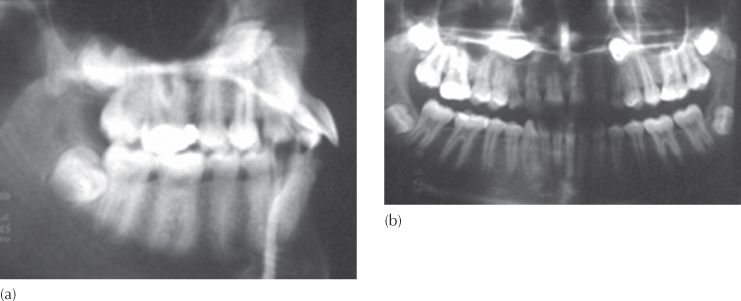

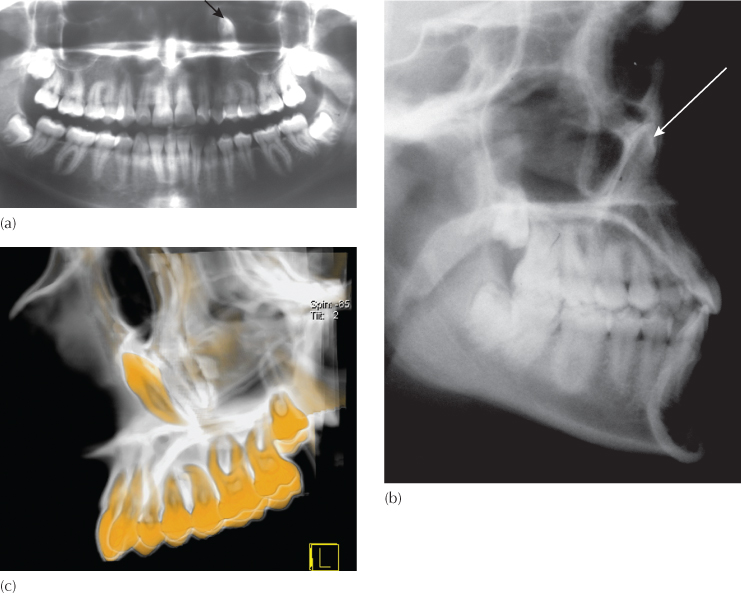

(a, b) The panoramic and lateral cephalometric views of this young female patient show the left maxillary canine (arrows) to be in close relation with the floor of the orbit of that side. It was important to establish its exact location in the three planes of space and whether further ‘eruptive’ movements in the present direction would threaten the eye. (c–e) Three-dimensional computerized tomographic views of the tooth provide accurate positional information with which to consult the ophthalmologist.

Incorrect Positional Diagnosis

Inadequate or inappropriate use of imaging techniques may sometimes give the operator a false impression of the position of an unerupted tooth. Often, films exist, but are simply not considered as contributory because positional diagnosis was not the original intention for obtaining the particular view concerned. As a routine, most orthodontists insist that the initial records of all their new patients include a panoramic, lateral cephalogram and sometimes a postero-anterior cephalogram. The panoramic films are used to ensure the presence of all the teeth and to register their state of development, and the cephalograms are studied and evaluated by the measurement of angles and distances between anatomic and dental structures. An undetermined but significant proportion of our orthodontic and surgical colleagues fail to exploit all the information that is contained in these films, particularly in regard to three-dimensional diagnosis of impacted tooth position (Figure 12.13). The patient is then further irradiated in the search of information already available.

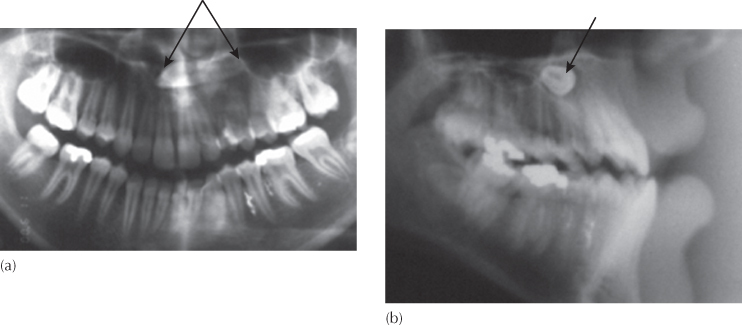

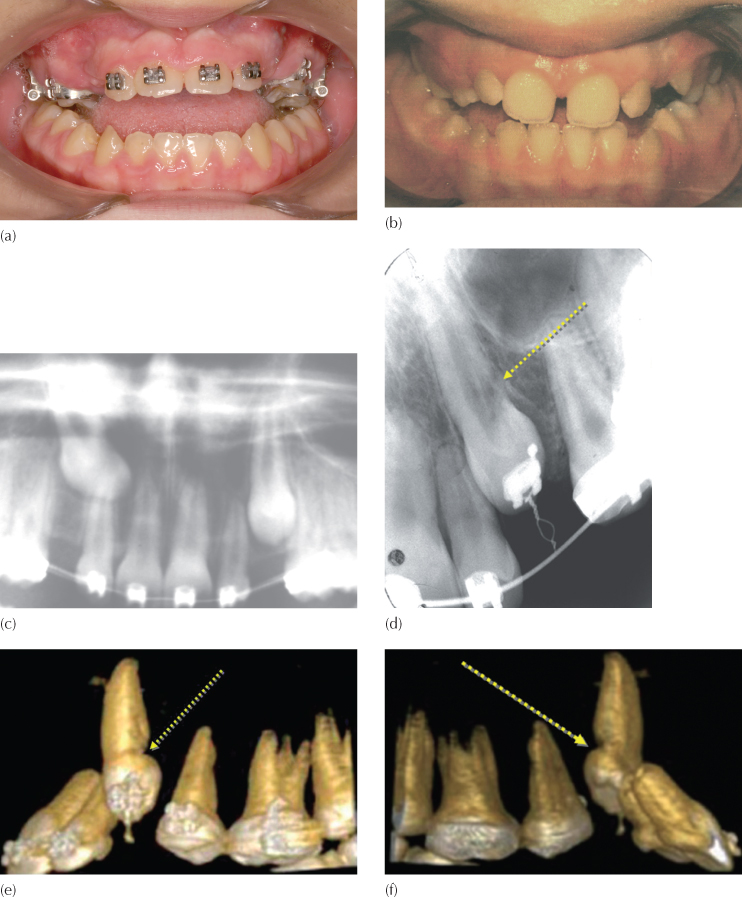

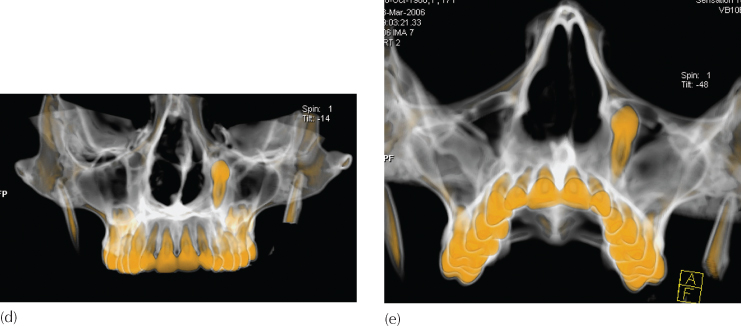

Fig. 12.13 A case of mistaken identity.

(Courtesy of Dr N. Shpack.)

(a) An occlusal view of a patient with an unerupted maxillary left central incisor. (b) The anterior occlusal view of the maxilla shows the typical appearance of a classical dilacerate central incisor, with the crown viewed in its long axis and the apical portion of the root pointing superiorly. (c) The cephalogram confirms the position of the crown high up and labial, adjacent to the root of the nose. (d) Excessive space had been deliberately made and a rectangular archwire placed, ready to be used as the base from which to apply traction to the impacted tooth. After the second surgical exposure an elastic ligature was tied to the labial archwire. However, the site of the first surgical exposure was mistaken and the decision was made through inadequate attention being given to information that was readily available from the radiographs. The exposed root apex of the tooth (arrow) can be clearly seen in the mid-palate. This tooth was subsequently extracted.

We have discussed wildly ectopic teeth as one of the factors that a patient may present to us for which the orthodontic/surgical modality may not provide the best treatment solution. However, to arrive at this decision a careful analysis of the orientation of the tooth in its ectopic location needs to be made, and />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses