CHAPTER 12

Surgical Management of the Airway

Christopher J. Haggerty

Private Practice, Lakewood Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Specialists, Lees Summit; and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Missouri–Kansas City Kansas City, Missouri, USA

Surgical Cricothyrotomy

An emergent airway when other methods of securing an airway have failed or are not possible.

Indications

When an acute emergent airway is indicated and oral and nasal intubation devices are not available or are not possible due to a mechanical airway obstruction such as an expanding hematoma, hypopharyngeal obstruction, angioedema, retropharyngeal abscess, or laryngeal edema.

Contraindications

- Pediatric patients under the age of 10. In pediatric patients, surgical cricothyrotomy can damage the cricoid cartilage and lead to subglottic stenosis

- Relative contraindications include complete or partial transection of the airway, laryngeal fracture and injury to the cricoid cartilage

Anatomy

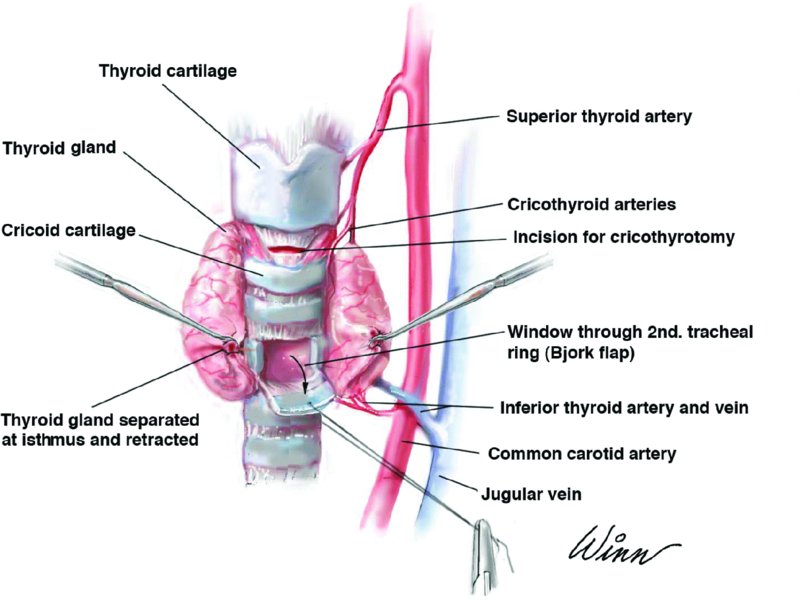

Cricothyroid space: The cricothyroid space is located between the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage and the superior border of the cricoid cartilage. The cricothyroid space spans 20–30 mm in its horizontal dimension and 8–10 mm in its vertical dimension. Within this space lies the cricothyroid membrane (Figure 12.1). There are no large vessels, glandular structures, or complex fascial or muscular layers overlying the cricothyroid membrane.

Figure 12.1. Illustration depicting trachea anatomy and the ideal locations of cricothyrotomy and tracheotomy placement.

Cricothyrotomy Landmarks

- The greater prominence of the thyroid cartilage

- The lesser prominence of the cricoid cartilage

- Between these two landmarks is the cricothyroid space.

Cricothyrotomy Layers

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue

- Cervical fascia

- Cricothyroid membrane

Surgical Cricothyrotomy Technique

- The patient is positioned with hyperextension of the neck (if no cervical spine injuries) for better visualization of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages.

- The skin is prepped, and local anesthetic containing a vasoconstrictor is injected to aid in pain control and hemostasis. Avoid excessive local anesthetic as this will obscure landmarks.

- If time permits, transtracheal injections are performed to decrease cough reflex (for an awake patient).

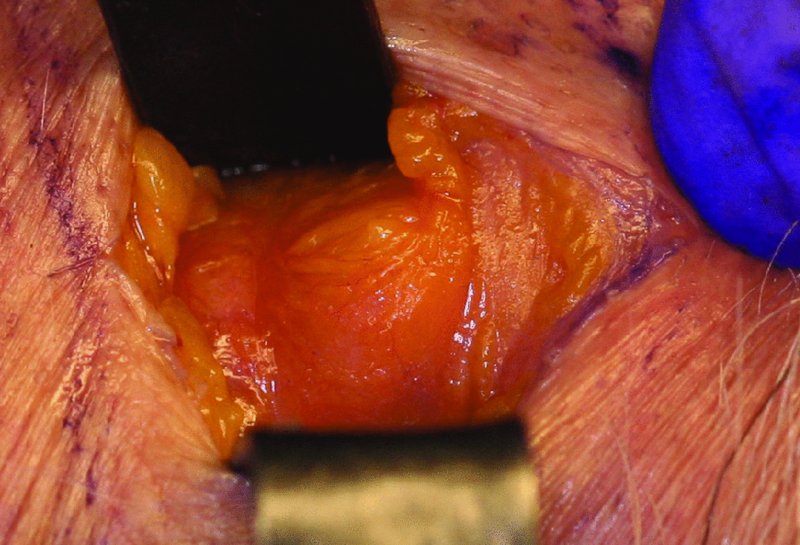

- With the nondominant hand, stabilize the thyroid cartilage between the thumb and middle finger, and palpate the cricothyroid space with the index finger. With the dominant hand, make a 3–4 cm vertical midline incision over the inferior portion of the thyroid cartilage extending inferiorly to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (see Figure 12.2 in Case Report 12.1). A vertical incision is utilized in an emergent situation to decrease the risk of vascular injury and to decrease the operating time from the skin to the cricothyroid membrane. The incision extends through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and cervical fascia to the thyroid and cricoid cartilage, exposing the cricothyroid membrane. The thumb and middle finger are used to apply a slight downward pressure to separate the skin edges after the incision. The incision should be made in a single, continuous swipe. If arterial bleeding is encountered, suspect the cricothyroid branches of the superior thyroid artery, which enter the cricothyroid membrane superiorly.

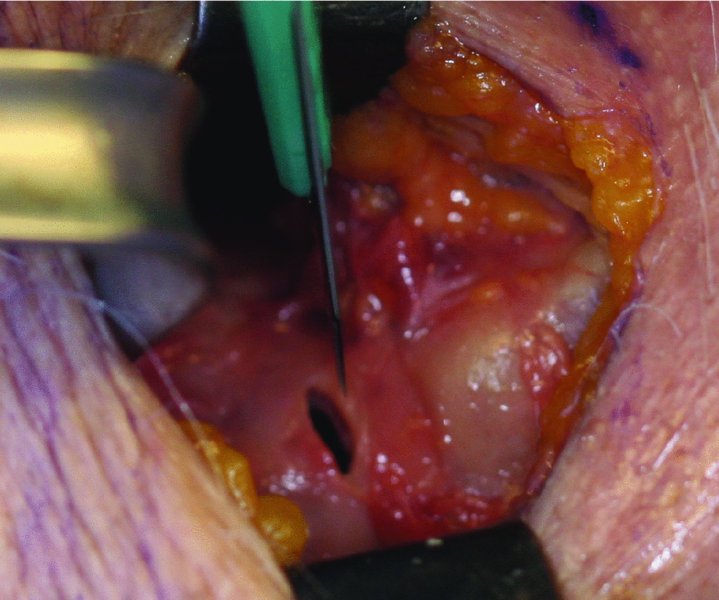

- Incise through the cricothyroid membrane in a horizontal manner, and place a scalpel handle or scissors/hemostat to enlarge the cricothyrotomy opening (Figure 12.3, Case Report 12.1).

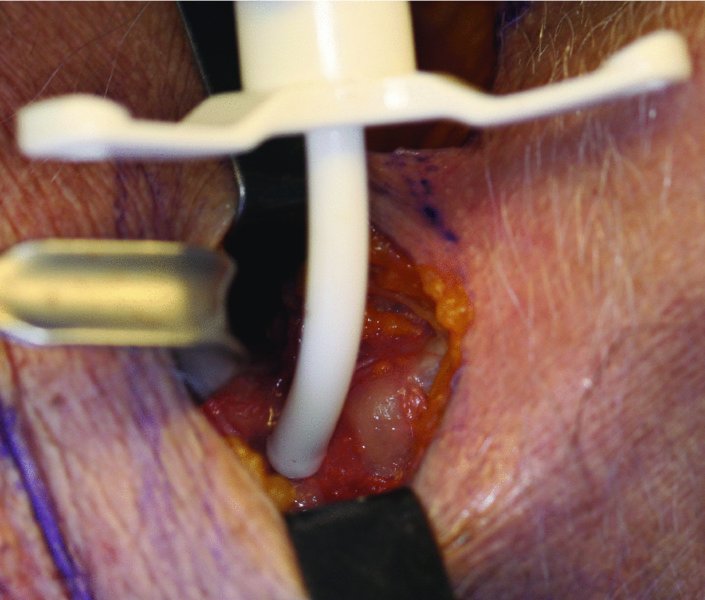

- Place a pediatric uncuffed tracheotomy tube or lubricated tracheotomy tube (Shiley number 4) into the trachea through the cricothyroid space (Figure 12.4, Case Report 12.1).

- Attach the anesthesia circuit, check for end-tidal CO2, and perform bilateral chest auscultation.

- Secure the tube to the skin with sutures and a cloth tie around the neck, or convert the cricothyrotomy to an open tracheotomy. Do not close the skin incision as this can lead to subcutaneous emphysema.

Figure 12.2. A 3–4 cm vertical midline incision is initiated over the inferior portion of the thyroid cartilage and extended caudally to the cricoid cartilage.

Figure 12.3. The cricothyroid membrane is identified between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages. A #15 blade is used to penetrate the cricothyroid membrane, and an osteum is created.

Figure 12.4. An airway device is inserted into the cricothyroid space.

Complications

Cricothyrotomy complications coincide with tracheotomy complications.

Key Points

- With any emergent surgical airway procedure, a midline vertical incision allows for faster access to the trachea and minimizes the risk of arterial and venous bleeding.

- There is no definitive evidence to support the conversion of a cricothyrotomy to a tracheotomy. Because most cricothyrotomies are performed in acute obstructive situations (anaphylactic edema, expanding hematoma, and abscess formation), the need for prolonged mechanical ventilation is often unnecessary.

- A true surgical cricothyrotomy is contraindicated in children under the age of 10 years or in patients who weigh less than 40 kg. In pediatric emergent airway situations, a needle cricothyrotomy should be utilized. There are numerous commercial needle cricothyrotomy kits available. Some utilize 12–14-gauge needles that can be inserted directly into the cricothyroid space and attached to a jet ventilation apparatus. Other kits allow for the placement of a needle into the cricothyroid space and allow for the changing of a specific catheter over a guide wire. All needle cricothyrotomies need to be converted to a definitive airway immediately as they are highly unstable due to dislodgement of the needle and loss of the airway.

References

- DiGiacomo, C.J., Neshat, K., Angus, L.D.G., Simpkins, C.O., Sadoff, R.S. and Shaftan, G.W., 2003. Emergency cricothyrotomy. Military Medicine, 168, 541–4.

- Hart, K.L. and Thompson, S.H., 2010. Emergency cricothyrotomy. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 18, 29–38.

- Macdonald, J.C. and Tien, H.C.N., 2008. Emergency battlefield cricothyrotomy. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178, 1133–5.

- OMFS Knowledge Update. Available from http://www.aaoms.org/members/meetings-and-continuing-education/oms-knowledge-update/

Tracheotomy

A definitive surgical airway for utilization in both emergent and non-emergent (elective) situations.

Indications

- Upper airway obstruction (edema, expanding hematomas, infections, and facial trauma resulting in mechanical airway obstruction)

- Significant facial injuries requiring maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) when nasal intubation is contraindicated (ie. combined mandibular and NOE type fractures)

- Head and neck tumor patients

- Inability to intubate

- Prolonged intubation or positive ventilation requirements

- Failure to wean from mechanical ventilation

- Loss of normal laryngeal function as a result of trauma or oncologic surgery

- Pulmonary insufficiency from either acute or chronic respiratory failure

- Severe obstructive sleep apnea

Contraindications

- There are no absolute contraindications for tracheostomy

- Relative contraindications include tracheal infection and significant burn injuries

Anatomy

Tracheotomy Landmarks

- The greater prominence of the thyroid cartilage

- The lesser prominence of the cricoid cartilage

- Sternal notch

Tracheotomy Layers

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue

- Platysma muscle

- The superficial (investing) layer of the deep cervical fascia, which splits to invest the SCM and trapezius muscles

- The midline infrahyoid linea alba which is formed from the fusion of the superficial (investing) and the middle (pretracheal) cervical fasciae

- The thyroid isthmus may be identified at the level of the second tracheal ring

- The pretracheal (middle) layer of the deep cervical fascia which invests the infrahyoid (strap) muscles, thyroid gland, trachea and esophagus

- Tracheal rings

Tracheotomy Procedure

- The patient’s head is placed in the midline of the table with cervical hyperextension (unless c-spine injury is suspected).

- The patient is prepped and draped from the inferior mandible to a point several centimeters below the sternal notch.

- A sterile marking pen is used to mark the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage, the cricoid cartilage, and the sternal notch.

- A 3–4 cm horizontal line is drawn with a sterile marking pen 2 cm inferior to the cricoid cartilage or midway between the cricoid cartilage and the sternal notch (Figure 12.6). This line will represent the skin incision and corresponds to the level of the second and third tracheal rings.

- Local anesthetic is injected under the horizontal line of the marker superficial to the platysma muscle. In an emergent situation with an awake patient, a transtracheal injection is used to decrease the cough reflex.

- A 3–4 cm horizontal skin incision is placed over the horizontal line (Figure 12.7). The incision initially transverses skin, subcutaneous tissue and the platysma muscle (if present). Electrocautery is used for hemostasis of subcutaneous bleeding. In elective tracheotomy, a horizontal skin incision has the advantage of improved cosmesis following secondary revision. Excessive lateral extension of the incision can lead to severance of the anterior jugular veins. In an emergent tracheotomy, a midline vertical incision allow for faster access to the trachea and minimizes the chance of arterial and venous bleeding.

- After transecting the platysma muscle, a vertical incision is performed through the superficial (investing) layer of the deep cervical fascia.

- Loose connective tissue is retracted laterally, and the linea alba and strap muscles are identified.

- Blunt dissection is carried through the midline avascular linea alba separating the strap muscles of the anterior neck until the thyroid isthmus and the pretracheal fascia are identified (Figure 12.8). If the thyroid isthmus is noted to cross over the second and third tracheal rings, it is divided with electrocautery. Failure to cauterize the transected thyroid isthmus can lead to postoperative bleeding. Failure to stay within the midline (within the avascular linea alba) during the initial dissection can result in muscle bleeding and lateral dissection of the trachea. The lateral sulcus between the trachea and esophagus contains the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Damage to this nerve results in impaired vocal cord function.

- Kittner pledgets are used to remove the pretracheal fascia and to expose the cricoid cartilage and tracheal rings.

- The tracheotomy cuff is lubricated and tested (inflated) prior to tracheal ring incision to ensure that the cuff works appropriately. Occasionally, the tracheotomy tube may be torn upon insertion into the trachea or may be too large for passive insertion into the surgical stoma. A second, smaller tracheotomy tube is always available as a backup.

- A cricoid hook is used to engage and elevate the cricoid cartilage upward and superiorly to gain better visibility of the tracheal rings.

- Prior to entering the trachea, it is paramount that the incision site is hemostatic in order to improve visualization and to minimize postoperative bleeding.

- The anesthetic gases are stopped, and the FiO2 is decreased to less than 30% to minimize the opportunity for airway fire.

- The ideal placement of the tracheal incision is through tracheal rings 2 and 3. Numerous types of tracheal incisions can be utilized. A simple “T” or cross incision can be made through tracheal rings 2 and 3 with an #11 blade, and a tracheal dilator can be used to enlarge the size of the surgical stoma. Alternatively, a Bjork flap (inverted U-flap) can be placed through tracheal rings 2 and 3 (Figure 12.9). The width of the base of the Bjork flap should be one-third of the tracheal diameter. 2-0 stay sutures are placed within the nonhinged border of the cartilage window. Appropriately positioned stay sutures will aid in the retraction of the Bjork flap during tube insertion. The stay sutures may be tied to the skin incision to reflect the flap open, or they can be taped to the patient’s anterior chest wall with steri-strips at the completion of the procedure. The Bjork flap has the advantage of creating a stable tract for tube reinsertion should accidental decannulation occur in a noncontrolled setting. For patients requiring prolonged or permanent mechanical ventilation, a permanent surgical stoma can be created by removing a wedge of cartilage the size of the Bjork flap from the anterior tracheal wall at the level of tracheal rings 2–3.

- After creation of a surgical stoma through tracheal rings 2 and 3, the anesthesia team is asked to slowly pull back the endotracheal tube (Figure 12.9). Once the endotracheal tube has moved superior to the surgical stoma, an unfenestrated tracheotomy tube with its obturator is placed into the tracheal stoma with gentle inferior pressure and following the natural curvature of the trachea (Figure 12.10). The obturator is removed, and the inner cannula is inserted. The tracheotomy tube cuff is inflated, and the anesthesia circuit is attached (Figure 12.11).

- The anesthesia team is asked to check for end-tidal CO2 and bilateral breath sounds.

- The tracheotomy flange is secured with a cloth tie around the neck and to the skin with 2-0 sutures (Figure 12.11). The previously placed stay sutures are secured to the skin of the anterior chest wall with steri-strips if they were not secured to the skin incision. A split gauze />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses