CHAPTER 45

Benign Tumors of the Jaws

Christopher M. Harris1 and Robert M. Laughlin2

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Virginia, USA

2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, California, USA

Non-odontogenic Tumors

Non-odontogenic tumors include connective-tissue tumors, vascular lesions, reactive lesions, and neurogenic tumors. The clinical presentation and treatment of these lesions vary. This section will describe the general classification of common non-odontogenic tumors and highlight standard treatments. All lesions should be treated individually based on their unique histopathology, aggressiveness, and clinical and radiographic presentation. Please refer to Appendix 3 for further treatment guidelines.

Tumors of Connective Tissue

Osteomas

Osteomas are benign tumors of bone. They are commonly found within the skull, jaws, and sinuses. Osteomas are composed of cortical and cancellous bone in varying proportions. These lesions typically present as an asymptomatic mass, which can produce asymmetry of the jaw bones. Radiographically, these lesions appear as dense radiopaque projections of bone. Gardner’s syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with multiple osteomas. Gardner’s syndrome is associated with multiple osteomas, polyps of the large intestine, multiple epidermal skin cysts, and multiple impacted teeth. The colon polyps in Gardner’s syndrome are considered premalignant, and a referral to a colon and rectal surgeon is recommended due to the certain malignant transformation of these lesions. Treatment is with tumor excision. Recurrence is rare.

Osteoblastomas

Osteoblastomas are rare, benign tumors of bone. They commonly occur in the long bones and spinal column. They have a peak incidence within the third to fourth decades of life and occur more frequently in males. The mandible is the most commonly affected craniofacial bone. Osteoblastomas may be asymptomatic and found on routine exam. However, localized pain and swelling are commonly seen. Pain is unique in that in many cases it is relieved by aspirin. Radiographically, the osteoblastoma can resemble other benign and malignant tumors. Osteoblastomas are typically radiolucent (early) with radiopaque structures within the lesion (later). The lesions can be well defined or poorly defined. The lesions often have a radiolucent rim associated with them. Teeth may be displaced, and/or resorption of roots may be seen.

Histologically, the osteoblastoma is similar to the osteoid osteoma. These are differentiated mainly by clinical features and size. Osteoblastomas demonstrate osteoid tissue and interconnected trabeculae of woven bone. These trabeculae are surrounded by a single layer of osteoblasts referred to as osteoblastic rimming. A fibrovascular stroma and osteoclasts are also seen. Aggressive osteoblastomas and low-grade osteosarcomas can look similar histologically. Treatment of osteoblastomas is with excision or aggressive curettage. Recurrence is uncommon with appropriate treatment. Recurrence is believed to arise from incomplete removal rather than inherent properties of the lesion. Aggressive osteoblastomas, however, have been reported to have higher recurrence rates and often require resection with definitive margins.

Chondromas

Chondromas are benign cartilaginous lesions of the jaws. They may occur centrally or peripherally. They are exceedingly rare in the head and neck. They are thought to arise in areas where embryonic cartilaginous cell rests are present. Therefore, the condyle, coronoid process, base of skull, and anterior maxilla are commonly involved sites. Radiographically, chondromas are well-demarcated radiolucencies. Local bone destruction should raise suspicion for malignancy. Chondromas have a peak incidence within the third and fourth decades of life and demonstrate an equal sex predilection. Histologically, they demonstrate mature hyaline cartilage. Treatment should be directed at total tumor excision due to the similarities of low-grade chondrosarcomas histologically.

Vascular and Reactive Lesions

Central Giant Cell Granulomas (CGCGs)

CGCGs are generally accepted to be nonneoplastic entities that behave like neoplasms. Whether these lesions are inflammatory, reactive, or true neoplasms is still debated. The lesions have been described as nonaggressive and aggressive. Aggressive lesions can cause pain, root resorption, cortical expansion and perforation, mucosal involvement, and higher recurrence rates after treatment. Nonaggressive lesions tend to be asymptomatic and do not have the above features. CGCGs have a peak incidence within the third, fourth, and fifth decades of life and have a higher predilection in females. Radiographically, these lesions can appear as unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies with noncorticated borders. Histologically, CGCGs demonstrate multinucleated giant cells (osteoclasts) scattered within a spindle cell background. Hemosiderin and erythrocytes may be seen. Fibrosis, osteoid, and bone may also be seen. Histological similarities to Brown tumors and aneurysmal bone cysts are noted. Hyperparathyroidism should be ruled out in these patients. Aneurysmal bone cysts may be a cystic variant of CGCGs. Cherubism also has similar histologic findings, but can usually be ruled out with clinical findings.

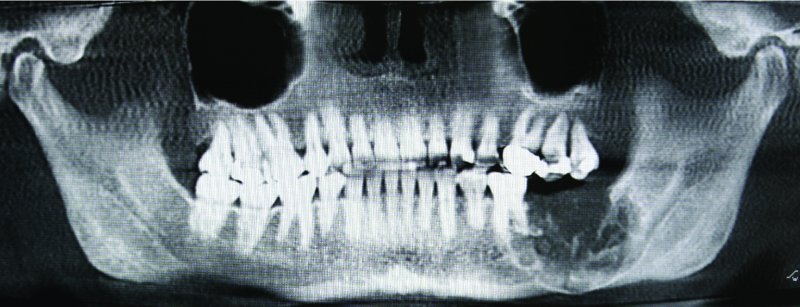

Figure 45.1. Radiograph demonstrating a multiloculated, aggressive, expansile hard tissue lesion located within the left posterior mandible with root resorption, and involvement of the inferior border of the mandible.

Various treatment modalities have been described in the current literature. Surgical curettage has a nearly 20% recurrence rate. Intralesional steroid injections have been used with mixed results. The protocol typically used includes a 50/50 mixture of lidocaine and triamcinolone, injecting 2 mL per 1 cm of lesion. Intralesional steroid injections are typically performed weekly for a total of 6 weeks. Calcitonin injections (100 μ/day) have been performed for up to 24 months with reported success. Subcutaneous interferon therapy has also been utilized. Nonsurgical treatments modalities frequently do not resolve the CGCG, but may allow for surgical intervention with less morbidity and cosmetic deformity and should be considered for large lesions. CGCGs that exhibit aggressive behavior, are recurrent or are refractory to intralesional steroid injections may be treated with peripheral ostectomy or resection with 5–10 mm margins.

Central Hemangiomas

Hemangiomas are benign proliferations of vascular tissues. It is debated whether hemangiomas are a proliferation of endothelium (true neoplasm) or a hamartomatous proliferation of mesoderm, which undergoes endothelial differentiation. Regardless of the etiology, they are potentially life-threatening entities. They are most commonly identified within the posterior mandible, but are otherwise rare within the jaws. They have a peak incidence within the first and second decades of life and a female predilection. Hemangiomas typically present as painless, firm swellings of the underlying bone. Patients may report a pulsation over the lesion. Teeth may be mobile with bleeding around the gingival margins. A bruit and thrill may be present. However, many hemangiomas are asymptomatic and present with none of the above findings. Radiographically, the lesions may be unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies. The multilocular variant has been described as the classic soap bubble or honeycomb appearance. Root resorption and cortical expansion with thinning may be seen, and phleboliths may be noted. There is no absolute pathognomonic radiographic finding for central hemangiomas; therefore, all lesions within the jaws should be initially treated as if they have a vascular component. Lesions that are suspicious for hemangiomas should undergo needle aspiration prior to biopsy. Aspirations that reveal frank blood are nearly pathognomonic for a vascular lesion. Angiography is required prior to any surgical manipulation of these lesions due to the potential for life-threatening hemorrhage and airway embarrassment. Angiography can demonstrate the borders of the lesion and afferent feeding vessels, and can be utilized for selective embolization prior to surgical removal. Embolization therapy with surgical removal (curettage or resection) the surgical ligation of afferent vessels, followed by surgical removal (curettage or resection), are the preferred therapies. Recurrence rates are low with complete removal of the lesion.

Fibrous Dysplasia (FD)

FD is a benign, non-encapsulated neoplasm characterized by cellular fibrous connective tissue and irregular islands of metaplastic bone replacing normal bone. FD occurs by mutations of the gene GNAS-1 (guanine nucleotide-binding protein, α-stimulating activity polypeptide-1). Postnatal mutations will cause localized monostotic disease. Mutations affecting stem cells in embryonic stages will cause systemic conditions (i.e., Jaffe–Lichenstein or McCune-Albright syndromes) characterized by defects in multiple cell lines resulting in multiple bone and cutaneous lesions, as well endocrine abnormalities.

FD commonly is discovered within the second decade of life. Sex predilection is equal. The lesions are typically nonpainful and expansile. Displacement of adjacent structures is common. Maxillary involvement is more prevalent than mandibular involvement. With maxillary involvement, other adjacent facial bones may be involved. This is described as craniofacial fibrous dysplasia. Growth generally ceases with skeletal maturation. Radiographs demonstrate an expansile “ground-glass” lesion with poorly defined borders. Histologically, the lesion is characterized by a cellular fibrous tissue with woven bone trabeculae that do not connect interspersed throughout this background. The bone trabeculae have been classically described as resembling “Chinese characters.” The edges of the lesion fuse with the normal bone without a capsule. Treatment involves resection of small lesions. Surgical reduction and contouring are performed with larger lesions that cause functional or aesthetic concerns. In up to 50% of cases, repeated debulking procedures are necessary until growth ceases. Long-term surveillance is needed due to the possibility of malignant transformation.

Odontogenic Tumors

Odontogenic tumors arise from structures involved with tooth formation. Benign odontogenic tumors encompass a variety of lesions within the jaws. Odontogenic tumors vary significantly both histologically and with their clinical behavior. Many odontogenic tumors are true benign neoplasms, whereas others are extremely aggressive, locally destructive lesions. Malignant variants of these lesions are also encountered. This section will describe the general classification of these tumors and highlight commonly encountered lesions. All lesions should be treated individually based on their unique histopathology, aggressiveness, and clinical and radiographic presentation. Please refer to Appendix 3A for further treatment guidelines.

Benign odontogenic tumors can be characterized by the embryonic tissue of origin. Classifications include (i) odontogenic epithelium, (ii) odontogenic ectomesenchyme (primarily), and (iii) mixed odontogenic epithelium and ectomesenchym/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses