Plaque Biofilm and Disease Control for the Periodontal Patient

Gwen Essex, Based on the original work by

Dorothy A. Perry and Phyllis L. Beemsterboer

• List the goals for plaque biofilm control for the periodontal patient.

• Recognize the role of plaque biofilm removal as an essential element in dental hygiene treatment for patients with periodontal disease.

• Describe why plaque biofilm control is more complex for periodontal patients than for those without clinical attachment loss.

• Evaluate interproximal plaque biofilm removal techniques that permit access to root surface concavities and furcations.

• Differentiate the methods for toothbrushing and interproximal plaque biofilm removal for patients with periodontal disease.

• Compare the effectiveness and uses of supragingival and subgingival irrigation.

• Identify effective chemical plaque biofilm control agents and their indications for use.

• Describe the role of motivation in gaining compliance of patients for plaque biofilm control programs.

Plaque as a Biofilm and an Etiologic Agent

A number of classic studies provide evidence of the importance of supragingival plaque control. Löe and colleagues1 showed the cause-and-effect relationship between the accumulation of bacterial plaque biofilm and the development of gingivitis in adults within 21 days. The gingivitis was reversible within 7 days when proper plaque control was initiated. Supragingival plaque becomes dominated by gram-negative microbial species as it ages. These gram-negative bacteria are responsible for the development of a subgingival biota associated with periodontal disease.2 Thorough toothbrushing to remove supragingival plaque has been shown to limit subgingival plaque growth in monkeys.3 Further more, adequate supragingival plaque control incorporated into periodontal maintenance programs was found to limit periodontal attachment loss in adults.4 Figure 12-1 shows the effects of plaque accumulation related to gingival inflammation.

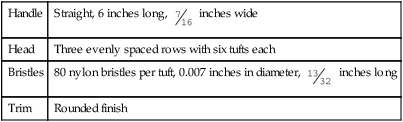

A, Day 1: A healthy gingiva with pink tissue that conforms to the architecture of the teeth. B, Day 1: A healthy gingiva disclosed to show good plaque control (day numbers are marked on central incisor). C, Day 11: Gingiva after 11 days with no plaque biofilm control. Note the rolled margins of the free gingiva and reddened marginal gingiva. D, Day 11: Disclosed to show biofilm accumulation. E, Day 21: Heavy plaque biofilm deposits and gingival swelling; the tissue bleeds on gentle probing. F, Day 21: Disclosed plaque biofilm deposits. G, Day 28: One week after plaque biofilm control was instituted on the right side of the mouth. Note the improved tissue health, decreased gingival redness, and conformity to the architecture of the teeth on the patient’s right side. H, Day 28: Disclosed dentition showing mature plaque biofilm remaining on the left side of the mouth.

Current understanding of plaque as a biofilm (see Chapter 4) highlights the importance of good daily mechanical plaque biofilm control. Mature plaque biofilm is a heterogeneous mass with open, fluid-filled channels used for the movement of nutrients and waste products. The colonies of bacteria making up the plaque mass facilitate each others’ growth and the host provides an essential source of nutrients. Plaque bacteria are a complex group of species that are interdependent and adhere to tooth surfaces in such a way as to limit the diffusion of antimicrobial substances.5 In light of this understanding, mechanical disruption of the bacterial mass is essential for the treatment of gingival and periodontal diseases.

Goals of Plaque Biofilm Control for the Periodontal Patient

Patient Motivation

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of plaque control for the periodontal patient is motivation to initiate and continue a lifelong process of improved daily plaque biofilm removal. Most periodontal patients have poor plaque control, which has contributed to the disease process. The habits of a lifetime are hard to change and new oral hygiene procedures will likely require a greater investment in time, from 15 to 30 minutes per day. Research on the topic of compliance and adherence to plaque control procedures indicates that engagement activities such as diaries, logs, quizzes, discussions, positive reinforcement, or other behavioral techniques are more successful than brushing and flossing instructions alone.6 The dental hygienist should use this knowledge to educate, motivate, and encourage each patient to adopt the recommended procedures and then reinforce the behavioral changes over time. Often, the development of a professional trust and partnership with the patient includes several treatments and recall maintenance visits to facilitate patient adoption of difficult behavioral changes.

Complexity of Plaque Biofilm Control For The Periodontal Patient

Plaque control for periodontal patients usually involves more than toothbrushing and dental flossing, as illustrated by Figure 12-2. Significant areas of attachment loss are often associated with disease and can occur as a result of surgery to reduce periodontal pocket depths. Attachment loss results in exposure of tortuous root anatomy that patients must learn to clean mechanically. This situation is often complicated by deep probing depths.

Caries Control

A good plaque control program provides all aspects of prevention and maintenance. Proper oral hygiene to control gingival inflammation is important, but the prevention of dental caries is also significant for the periodontal patient. Root caries, as seen in Figure 12-3, is a great threat to the survival of the teeth when attachment loss and recession expose the roots to the oral environment. Teeth that could be maintained for years by treating the periodontal disease can be lost in weeks or months as a result of caries on the root surfaces or in furcation areas. An understanding of caries risk factors and methods for controlling caries make up an essential component of the educational information that dental hygienists must provide for periodontal patients. For a discussion of root caries and its management, see Chapter 17.

Maintenance of Gingival and Periodontal Health

Gingival and periodontal health, once restored through therapeutic efforts, however complex, cannot be maintained without the active participation and cooperation of the patient in performing daily supragingival plaque removal. An oral environment that is free of inflammation because of good plaque control rarely becomes reinfected, and further more, satisfactory treatment outcomes are more likely when patients adopt adequate personal plaque control regimens.7

Mechanical Plaque Removal

Toothbrushing

The toothbrush is the most widely accepted and adopted tool for cleaning the teeth. It is the modern version of the African twig or chew stick, a frayed branch used for mechanical cleansing. There is evidence of toothbrushes in China as early as 1000 BC, but the device did not receive wide distribution until the late eighteenth century. The first brushes were made of hog bristle, often with bone or ivory handles. The Victorians created elaborate handles, including many made of silver. Consequently, early toothbrushes were expensive and were often shared by the entire family. Examples of toothbrushes from the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries are shown in Figure 12-4.

In the 1930s, when nylon-bristled brushes were introduced, toothbrushes became affordable for everyone. Until the 1960s, most brushes sold were stiff-bristled (a legacy of the Victorian era), like the old hog-bristled brushes. Stiff-bristled brushes removed plaque but were associated with trauma to the tooth structure and gingiva.8 Because of the work of pioneers such as Arnim, Barclay, and Dr. Charles C. Bass, soft-bristled toothbrushes used with a controlled plaque biofilm removal technique have become the standard.

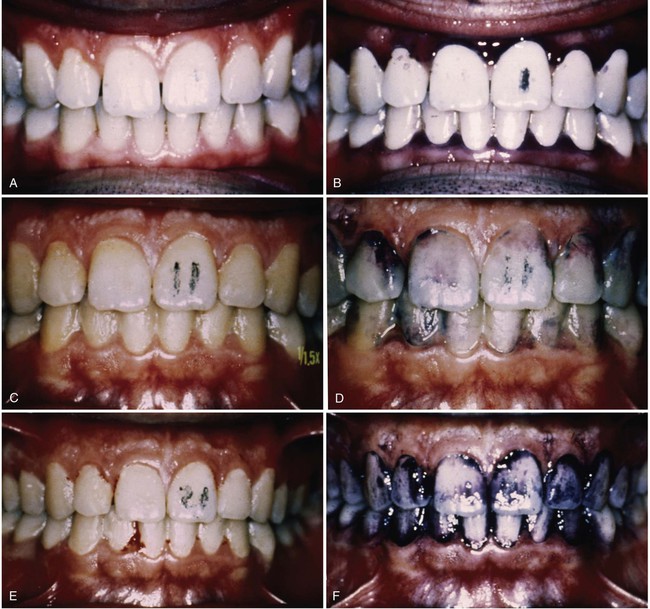

Bass9 proposed the optimum characteristics of toothbrushes. He studied bristle stiffness, scratching of the gingiva in humans and animals, gingival puncturing, bristle trim, and the presentation of bristles on the brush head. His recommendations are summarized in Box 12-1.

A review of toothbrushing behavior suggests that most Americans brush once daily, with the frequency increasing to twice daily as people get older. Generally, people brush because they believe they are reducing the incidence of decay and are not necessarily aware of the beneficial gingival health effects of plaque biofilm removal by the toothbrush. Interestingly, most people spend less than 1 minute brushing, concentrate on the upper teeth and buccal surfaces, and brush less on the lingual surfaces and lower teeth. Also, effective brushers were most often taught brushing techniques in a dental office.10 Awareness of the association between good plaque biofilm control and better gingival health may be increasing because of the extensive media advertising about gingivitis. However, the rationale for teaching good brushing techniques and emphasizing the importance of doing the job well is that it improves oral health.

Since Bass’s time, many toothbrushes have been marketed to the public. Very complex bristle designs, many with handle modifications, are available. Manufacturers claim superiority in one aspect of cleaning or another, but these claims are generally related to plaque removal alone, rather than improvements in gingival health. Minor variations in plaque biofilm removal as a result of brush design have not been shown to lead to clinically significant differences in gingival health. One toothbrush may work better than another in the hands of a particular patient, but there is no evidence demonstrating that one toothbrush design is superior to another.11 An example of an unusual toothbrush design with two brush heads is presented in Figure 12-5.

Toothbrushing Methods

• The Scrub toothbrushing method

• The Roll toothbrushing method

• The Charters toothbrushing method

• The Stillman toothbrushing method

No one method of brushing has been found to be superior to the others.12 The Charters and Stillman methods emphasizing gingival massage are primarily of historical interest because gingival massage has not been shown to improve healing. The best method is the one that suits the individual’s needs and abilities, and it is the responsibility of the dental hygienist to work with the patient to develop the most effective technique and to help the patient perform the task thoroughly.

Roll

The roll technique involves brushing the teeth the way they grow, down on the upper teeth and up on the lower teeth. Bristles are placed on the gingiva, and then the handle of the toothbrush is turned to stroke the bristles along the sides of the teeth. This action is repeated several times in each location, moving around the arches, until all the teeth are brushed. The technique requires a fair amount of concentration to apply the brush to each area and sufficient dexterity to “roll” the brush on the buccal and lingual surfaces. In addition, the rolling strokes must be performed slowly so that the gingival one third of the teeth will be adequately cleaned.12

Charters

The Charters technique requires placement of the brush at a 45-degree angle to the tooth surface, with the bristle ends pointing away from the gingiva but toward the interproximal surfaces of the teeth. The bristles rest on the gingiva, and pressure is applied to force the bristles between the teeth using a slight rotary motion. Then the brush is lifted from the gingiva and replaced in the same spot, repeating the massage three or four times. Essentially, the bristles are repeatedly pressed against the gingival margin and then lifted away to massage the tissue and increase blood flow. The bristles are also pressed into the occlusal surfaces with a slight rotary motion so that they fit into the pits and fissures. Charters also recommended the use of metal or wooden toothpicks for interproximal stimulation. Dental floss was to be used only to remove fibrous food caught between faulty contacts.13

Although the rationale for massage may be unproven, the effectiveness of the Charters method for plaque removal has been validated by at least one clinical study. The study subjects were instructed to use the technique and its effectiveness in removing all plaque was verified by a dental hygienist every day over the 6-week study period. In this case, the subjects used wooden interdental sticks, rather than metal picks, to ensure interdental cleaning.14

Stillman

Stillman also advocated toothbrush massage by describing a technique reputed to fill the gingival blood vessels with oxygenated blood. His technique required placement of the bristles pointing apically, but not at right angles to the gingiva, to minimize puncture. Pressure is placed on the bristles, causing them to flex and the tissue to blanch. Then the pressure is released. The procedure is repeated for all teeth in all areas of the mouth and the brush is rinsed several times with a salt water and sodium bicarbonate solution.15 This technique may result in plaque removal, although its effectiveness around the gingival margin is questionable.

Bass

Bass described his technique in relation to plaque removal as the goal of toothbrushing. He designed a method aimed at gingival and crevicular cleaning and described it as “applying the ends of the bristles to the areas with firm pressure and moving the brush back and forth (‘vibratory motion’) with short strokes, thereby dislodging soft material by the digging action of the ends of the bristles wherever they can be applied.”16 This technique requires the bristles of a soft, multitufted toothbrush to be placed at a 45-degree angle to the long axis of the teeth. The vibratory motion is used to force the bristles into the sulci and between the teeth as effectively as possible, as illustrated in Figure 12-6. The lingual surfaces of the anterior teeth can be brushed with the heel of the toothbrush for better access and all other areas with the length of the brush head. The occlusal surfaces are brushed with controlled back and forth motions. The Bass technique has been described as modified by the addition of the rolling stroke. This modified stroke is supposed to lift debris away from the gingiva. In practice, clinicians and patients often start with the vibratory motion described by Bass but then modify it in unique ways, such as bigger or circular strokes.

Powered Toothbrushing

Powered, or electric, toothbrushes are popular and useful devices. Many people prefer a powered toothbrush, or find it easier to use, particularly if they have dexterity problems. Powered toothbrushes are as effective as manual brushing for reducing plaque, gingivitis, and bleeding.17

Powered toothbrushes have different types of actions. The head portion of the brush can be vibrating, oscillating, rotary, or counter-rotary, or it can have a sonic vibration feature. All of these features have been shown to be effective when used correctly. Many studies comparing powered toothbrushes with manual ones have been published over the years. Studies of relatively short duration have demonstrated greater reductions in inflammation and plaque for the powered brushes.18 The Cochrane Collaboration (http://www.cochrane.org), an international volunteer organization that provides peer-reviewed assessments of published data in scientific literature, has presented a review of studies comparing manual with powered toothbrushes. The group identified 354 studies, of which 29 met the inclusion criteria for their analysis. Their results indicated that rotating-oscillating powered toothbrushes provided a modest clinical benefit to patients in reducing both plaque and gingivitis, whereas the other types of powered brushes performed as well as manual toothbrushes. These small differences in bleeding and plaque scores do not necessarily mean that patients will have less periodontal disease; further studies of the quality required by the Cochrane Collaboration are needed to answer this question.17 These data demonstrated some plaque biofilm removal advantages for some powered toothbrushes but are not sufficient evidence to recommend that everyone use a powered toothbrush. However, it is clear that powered toothbrushes have a place in the armamentarium of the dental hygienist.

Powered toothbrushes with sonic components cause hydrodynamic shearing forces of water that increase penetration of plaque removal onto the proximal surfaces. Studies have shown that these brushes offer, at best, modest improvements in interproximal cleaning and that they are not substitutes for other interproximal cleaning devices.7 Figure 12-7 illustrates the placement of the powered toothbrush head on the tooth surface.

Recommendations

Powered toothbrushes are useful and good tools for patients who have difficulty brushing or those who simply prefer powered toothbrushes. There is evidence to indicate that periodontal patients significantly decreased their plaque scores over a 3-year period when their manual toothbrushes were replaced with powered toothbrushes.19 The Cochrane analysis also suggested there are modest benefits in plaque and gingivitis reductions with oscillating-rotating powered brushes. Powered toothbrushes should be considered for plaque control in periodontal patients and adopted if appropriate for the individualized plaque biofilm control program.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

inches wide

inches wide inches long

inches long