12

Lip Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Lip cancer comprises 30% of all head and neck malignancies and is second only to cutaneous malignancies.1,2 The oral and maxillofacial surgeon (OMS) has a unique opportunity to participate in the diagnoses and management of these patients. General dental practitioners often identify premalignant and malignant lesions and have traditional referral pattern to their surgical colleagues and traditionally the OMS is greatly involved in the management of lip cancer.3,4,5 While the prognosis for early stage lip cancer is generally good,1 up to 20% of the patients can develop nodal metastasis. Those cancers with nodal metastasis are noted to be of larger size (greater than 2 cm) or higher histologic grade. Elective cervical lymphadenectomy can be justified for lip cancers that are very poorly differentiated or undifferentiated and for locally recurrent lip cancers when the initial tumor size is greater than 2 cm. High grade histologic tumors have been found to present with regional metastasis more frequently regardless of T stage.6

The incidence of lip cancer is approximately 10–12 cases per 100,000 persons in the United States,2 and sun exposure is one of the most common risk factors. The Sun Belt region in the south and southwest of the United States has been identified as having a greater prevalence of lip cancer. Other risk factors include smoking, particularly cigar and pipe smoking.7 Men represent 95% of all diagnosed cases8 and this is presumed to be due to traditional gender roles such as labor activities in the sun. Additionally, women may decrease their risk due to the use of lipstick or lip coverage.9 Generally, most patients are 53–66 years of age, likely due to a cumulative effect of chronic sun exposure. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histological variant reported at 90%,10 melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and minor salivary malignancies represent the minority of lesions.8

DIAGNOSIS/STAGING

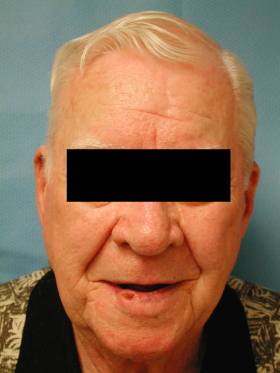

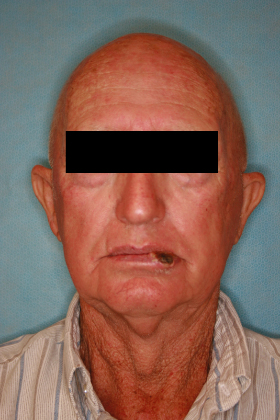

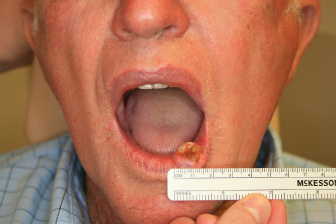

Lip cancer lesions are typically diagnosed early given the fact that the lesion is in a conspicuous area, which prompts individuals to seek treatment. These lesions may present with a variety of clinical features. A persistent ulcerative wound on the vermilion, and endophytic or exophytic variants are typical (Figs. 12.1, 12.2, and 12.3). Early lesions can present as a limited leukoplakia to advanced lesions being obviously malignant, invading the adjacent anatomic structures. The lower lip is most often affected and accounts for 89% of lesions. The upper lip and oral commissure represent 7% and 4% of lesions, respectively (Figs. 12.4, 12.5, 12.6).

Fig. 12.1. Frontal view of an 84-year-old male with an endophytic T2N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip.

(Miloro M. 2004. Peterson’s Principles in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 2nd ed., BC Decker Inc., Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.)

Fig. 12.2. Frontal view of a 76-year-old male with an exophytic T2N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the left lower lip.

(Miloro M. 2004. Peterson’s Principles in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 2nd ed., BC Decker Inc., Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.)

Fig. 12.3. Close-up view of the umbilicated exophytic T2 lesion.

(Miloro M. 2004. Peterson’s Principles in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 2nd ed., BC Decker Inc., Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.)

Fig. 12.4. Frontal view of a 73-year-old female with a T1N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the upper lip.

Fig. 12.5. Frontal view of a 78-year-old male with a T1N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the right oral commissure.

Fig. 12.6. Intraoral view of the right oral commissure squamous cell carcinoma.

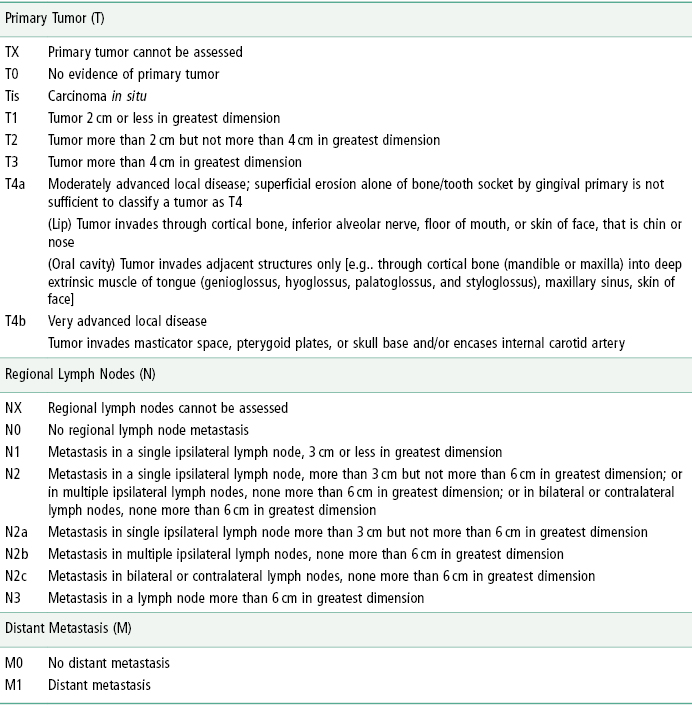

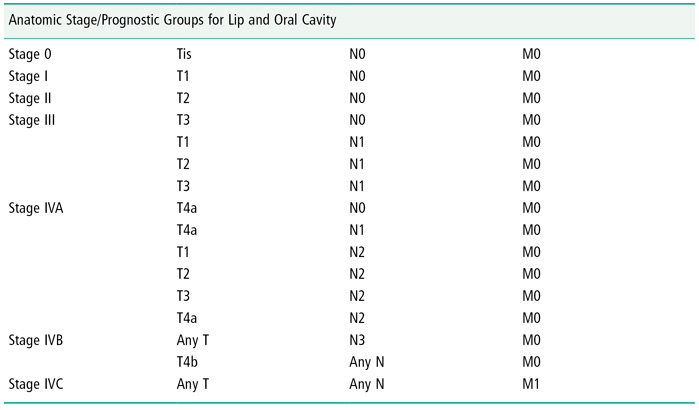

The American Joint Committee on Cancer has established the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification for staging lip cancer, which is also used in staging of oral cancer11,12 (Table 12.1). Seventy percent of all lip cancers present as stage I while stages II, III, and IV comprise 16%, 10%, and 4%, respectively.8 Diagnostic tools include a incisional biopsy, thorough history and clinical evaluation for cervical lymphadenopathy, and imaging of the neck most commonly via computed tomography (CT) with contrast or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) when indicated.

Table 12.1. American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) Classification

The mainstay in treatment modalities for lip cancer is surgical excision7,13 or radiation therapy. The surgical defect and the undesirable side effects of radiation contribute to the morbidity of treating lip cancer. Surgical margins for resection may vary with a 5-mm margin in lesions smaller than 10 mm in diameter and up to a 20-mm margin for larger lesions.14,15,16 Preoperative planning of the anticipated surgical defect is paramount. Maintaining the facial aesthetics, speech, and oral competence are the pivotal reconstructive goals.

Many proposed techniques have been utilized for lip reconstruction following ablative surgery. Options include primary closure, local tissue rearrangement and microvascular free tissue transfer. A simple approach when considering reconstruction is to estimate the size of the defect. T1 lesions may be managed with a wedge resection and primary closure due to elasticity of the perioral tissue. Vermilionectomy should be included with the wedge resection when indicated. For larger defects that are one-third to two-thirds of the lip, horizontal advancement flaps may be employed. For defects greater than two-thirds of the lip, a number of differing local tissue rearrangement techniques have been proposed (e.g., nasolabial flaps and fan flaps),17,18 (Figs. 12.7–12.12). Free flaps can also be employed for large defects [Figs. 12.13(a)–(e); Table 12.2). No matter which reconstructive option is utilized, many of the complications associated with the treatment of lip cancer revolve around the challenges to restore the premorbid function, anatomy, and aesthetics.

Table 12.2. Lip Reconstruction Techniques

| V Excision |

| Vermilionectomy with mucosal advancement |

| V-Y mucosal advancement flaps |

| Tongue flap |

| Transpositional flaps |

| Abbé–Estlander flap |

| Karapandzic flap |

| Bernard flap |

| Stair step flap |

| Circumoral advancement flaps |

| Cheek advancement flap |

| Gillies fan flaps |

| McGregor flaps |

| Microvascular free flap |

Fig. 12.7. Frontal view of an 86-year-old male with a large fungating T4N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip.

Fig. 12.8. Intraoperative view demonstrating planned excision margins.

Fig. 12.9. Intraoperative intraoral view of planned excision margins.

Fig. 12.10. Intraoperative view of defect and planned reconstruction with Bernard flaps.

Fig. 12.11. Immediate postoperative view of the lower lip reconstruction using the Bernard’s flaps technique. Note the wound tension and venous congestion.

Fig. 12.12. Dehiscence of a reconstructed lower lip. Secondary healing is occurring at the midline where the wound margins have broken down.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses