Chapter 12

Child Physical Abuse

Aim

To provide a review of the orofacial signs of child physical abuse and the role of the dental professional in child protection.

Objectives

After studying this chapter the reader should know the types of injuries that may be seen on the face and head in child physical abuse, and appreciate the availability of local designated doctors and nurses in child protection if there is concern.

Introduction

In the middle of the last century reports appeared in the USA of unexplained skeletal injury to children sometimes associated with subdural haematoma. When Kempe et al (1962) published their paper The Battered-Child Syndrome, the full impact of the physical maltreatment of children was brought to the attention of the medical community and subsequently the general public. Within a few years the majority of states in the USA had introduced laws that made it mandatory for physicians, dentists and other health-related professions to report suspected cases.

Prevalence

Every week children die as a result of abuse or neglect. In accident and emergency departments of hospitals, 10% of children younger than five years of age in the USA and 1.3 children per 1000 per year in Denmark will have injuries that are wilfully inflicted. In Britain at least one child per 1000 under four years of age per year suffers severe physical abuse – for example, fractures, brain haemorrhage, severe internal injuries or mutilation. In the USA more than 95% of serious intracranial injuries during the first year of life are the result of abuse.

Aetiology

Child abuse encompasses all social classes, but more cases have been identified in the lower socio-economic groups. Many cases of child abuse involve the child’s parents or persons known to the child. Young parents, often of low intelligence, are more likely to be abusers. Abuse is thought to be 20 times more likely if one of the parents was abused as a child.

Identification

The following list constitutes 10 pointers that should be considered when suspicions arise. None of them is pathognomonic on its own, neither does the absence of any of them preclude the diagnosis of child abuse (see Table 12-2).

-

Could the injury have been caused accidentally and if so how?

-

Does the explanation for the injury fit the age and the clinical findings?

-

If the explanation of the cause is consistent with the injury, is this itself within normally acceptable limits of behaviour?

-

Has there been a delay in seeking medical help, and are there good reasons for this?

-

Is the story of the ‘accident’ vague and lacking in detail; and does it vary with each telling, and from person to person?

-

The relationship between parent and child.

-

The child’s reaction to other people and any medical/dental examination.

-

The general demeanour of the child.

-

Any comments made by the child and/or parent that give cause for concern about the child’s lifestyle or upbringing.

-

History of a previous injury.

It is important to state that similar issues may be encountered in the abused, dentate elderly.

Types of Orofacial Injuries in Child Physical Abuse

At least 60% of cases diagnosed as child physical abuse have orofacial trauma. Although the face often seems to be the focus of impulsive violence, facial fractures are not frequent (Table 12-1). Soft-tissue injuries, most frequently bruises, are the most common injury. In addition, it is common for a particular child to have more than one injury. It is very important to state that there are no specific single injuries which are diagnostic or pathognomonic of child physical abuse.

| Involving the face | |

| Contusions and ecchymoses | 66% |

| Abrasions and lacerations | 28% |

| Burns and bites | 4% |

| Fractures | 2% |

| Involving the intraoral structures | |

| Contusions and ecchymoses | 43% |

| Abrasions and lacerations | 29% |

| Dental trauma | 29% |

|

Questions |

|

|

Observations |

|

Bruising

Accidental falls rarely cause bruises to the soft tissues of the cheek, but instead involve the skin overlying bony prominences such as the forehead or cheekbone. Bruises cannot be accurately dated, but bruises of widely differing vintages (Fig 12-1) indicate more than one episode of abuse. Bruises on the ear are commonly due to being pinched or pulled by the ear and there will usually be a matching bruise on the posterior surface of the ear.

Fig 12-1 Bruising of different vintages involving the skin overlying the side of the face and neck (courtesy of Munksgaard Publishing, 1994. Textbook and Colour Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth. Andreasen JO and FM (3rd edn.). Chapter 4: Child Physical Abuse).

Bruises or cuts on the neck are almost always due to being choked or strangled by human hand, cord or some sort of collar. Accidents to this site are extremely rare and should be looked upon with suspicion.

Bruising and laceration of the upper labial fraenum of a young child can be produced by forcible bottle feeding and may remain hidden unless the lip is carefully everted (Fig 12-2). A fraenal tear is not uncommon in the young child who accidentally falls while learning to walk (generally between eight to 18 months). A fraenal tear in a very young non-ambulatory patient (<1 yr) should however, arouse suspicion.

Fig 12-2 Bruising and laceration of upper labial fraenum.

Human hand marks

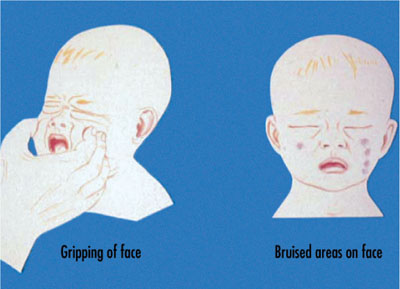

The human hand can leave various types of pressure bruises: grab marks or finger-tip bruises, linear mark or finger-edge bruises, hand prints, slap marks and pinch marks. Grab mark bruises can occur on the cheeks if an adult squeezes a child’s face in an attempt to aid feeding (Fig 12-3). Thumb marks appear on one cheek and two to four finger mark bruises on the other cheek. Linear marks are caused by pressure from the entire finger. In slap marks to the cheek, parallel linear bruises at finger-width spacing will be seen to run through more diffuse bruises (Fig 12-4). These linear bruises are due to the capillaries rupturing at the edge of the injury (between the striking fingers), as a result of being stretched and receiving a sudden influx of blood.

Fig 12-3 Bruising produced by squeezing a child’s face.

Fig 12-4 Slap mark bruise. Three parallel bruises at finger-width spacing can be seen to run through a more diffuse bruise (courtesy of Munksgaard Publishing, 1994. Textbook and Colour Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth. Andreasen JO and FM (3rd edn.). Chapter 4: Child Physical Abuse).

Bizarre bruises

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses