11 Surgical aids to prosthodontics, including osseointegrated implants

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed at this stage that you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTRODUCTION

A well-constructed removable prosthesis that replaces missing teeth will restore function and appearance. A removable prosthesis should be stable and have adequate retention and stability. To achieve this, the prosthesis should be seated onto well-shaped alveolar ridges with adequate basal bone and a healthy oral mucosa. There will ideally be no major vertical or horizontal skeletal discrepancy, which can compromise denture stability.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF PREPROSTHETIC SURGERY

The objectives of preprosthetic surgery are to help to:

Preprosthetic surgery may be undertaken to:

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES IN THE ORAL TISSUES AND MASTICATORY APPARATUS ASSOCIATED WITH AGE

Physiological changes in the oral tissues are sometimes a consequence of hormonal changes. For example, oral discomfort may occur in women without overt clinical signs, and denture wearing may aggravate the symptoms in some patients. In a few cases, oral discomfort may be attributed to the menopause, and the symptoms may resolve after hormone replacement therapy. It is therefore necessary to obtain a comprehensive history from the patient in order to identify accurately the cause of any oral discomfort associated with denture wearing. Nutrition can also play a part in oral discomfort; some patients with sore mouth may be anaemic.

ANATOMICAL CONSEQUENCES OF TOOTH LOSS

Loss of alveolar bone

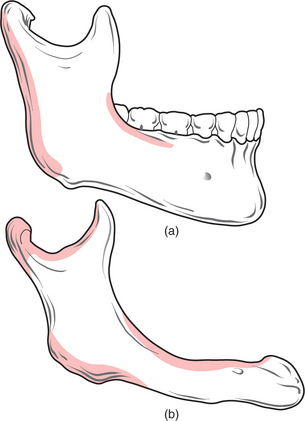

Changes occur in the morphology of the jaws after tooth loss (Fig. 11.1). The jaws are composed of alveolar and basal bone. The alveolar bone and periodontium support the teeth, but neither have a physiological function once the teeth are lost, and are therefore resorbed. Alveolar bone changes shape significantly with tooth loss, in both the horizontal and vertical planes, but the overall pattern of resorption is largely predictable. In the maxilla and in the anterior aspect of the mandible bone loss occurs typically in both the horizontal and vertical planes. In the posterior mandible the bone loss is mostly in the vertical plane.

After physiological resorption has occurred, the remaining jaw structure is termed the ‘residual ridge’. The bone that remains after alveolar bone has resorbed is termed ‘basal bone’. Marked resorption sometimes affects the entire mandible (Fig. 11.2). Basal bone does not change shape significantly unless it is subjected to excessive local forces, for example, in the edentulous anterior maxilla in association with retained natural lower incisors.

Other affected anatomical structures

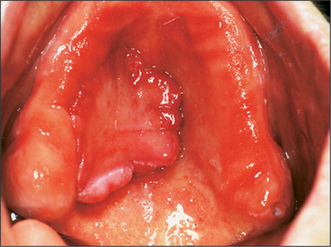

Other anatomical structures may become more prominent with tooth loss. The genial tubercles and their muscle attachments may become prominent in a patient with extensive resorption of the mandible, sometimes compromising denture stability. Maxillary or mandibular tori may also cause instability of a denture, or may be traumatized by it. A prominent fraenum (Fig. 11.3) can displace a denture during function, and may weaken the denture base so that it fractures through flexing.

Forces transmitted through the teeth during mastication are absorbed by the supporting structures (the periodontium and alveolar bone). In an edentulous patient, forces exerted by a denture are transmitted through the oral mucosa to the underlying bone. A denture must therefore fit well if trauma to the oral mucosa overlying an edentulous ridge is to be avoided.

CLASSIFICATION OF THE EDENTULOUS JAWS

Cawood and Howell (1988) classified the edentulous jaws according to the state of ridge resorption after tooth loss (Table 11.1). There are other classifications, but this one has been adopted internationally as a means of assisting communication and assessment of a patient’s edentulous state.

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Dentate |

| II | Immediately postextraction |

| III | Convex ridge form, adequate in height and width |

| IV | Knife-edge ridge form, adequate in height but inadequate in width |

| V | Flat ridge form, inadequate in height and width |

| VI | Loss of basal bone, which may be extensive but follows no predictable pattern |

THE IDEAL EDENTULOUS RIDGE

Most patients tolerate the loss of their natural teeth and subsequent denture wearing without difficulty. However, there may be extensive loss of alveolar bone after tooth extraction, resulting in an atrophic (flat or knife-edged) edentulous ridge (Fig. 11.4). In some patients this can make denture wearing difficult or uncomfortable. The prosthodontist may be able to modify a denture design to enhance its stability and retention, but this is not always possible. Surgery may therefore be required to enhance retention and stability of the prosthesis.

PREPROSTHETIC SURGERY PROCEDURES

Some of the procedures described below may be included in more than one category.

Soft-tissue procedures

Excision of hyperplastic tissue

Hyperplastic oral mucosa under or adjacent to a removable denture usually arises in response to chronic irritation, for example, from an overextended denture flange or a deficiency in the fitting surface of a denture, trauma from a sharp cusp on an acrylic tooth or an ill-fitting denture clasp. Poor denture design may also cause mucosal hyperplasia (Figs 11.5, 11.6). Surgery may be unnecessary if the cause of the hyperplastic tissue is identified and eliminated; the hyperplastic tissue will then usually diminish in size or resolve completely. Any residual tissue that inter-feres with denture construction can be removed via an elliptical incision as for an excision biopsy (see Ch. 8, p. 109). Where possible (e.g. in the buccal sulcus or on the cheek), the incision may be closed by suturing the wound edges together (primary closure). On the edentulous ridge, the periosteum is elevated to undermine the edges of the wound, and the edges of the mucoperiosteal flaps can then be advanced to achieve wound closure. A split-thickness skin graft may be required to cover extensive areas of denuded oral mucosa. A keratinized-free mucosal graft may be harvested from the hard palate for smaller areas. It is often beneficial to place a temporary soft lining in the existing denture after surgery, to minimize the likelihood of further irritation, prior to remaking the prosthesis.

Prominent labial fraenum

The flange of a denture may traumatize a prominent labial fraenum or muscle attachment (Fig. 11.3). If the fraenum is relatively small, this may be managed by trimming back the labial or lingual denture flange. However, the denture may be weakened and it might fracture if extensive trimming is undertaken to relieve the fraenum. Excision of the fraenum (fraenectomy) may be indicated to avoid this.

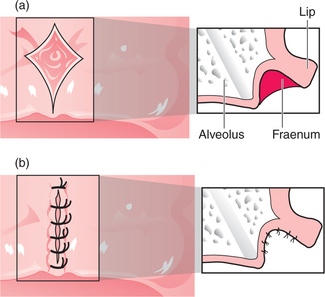

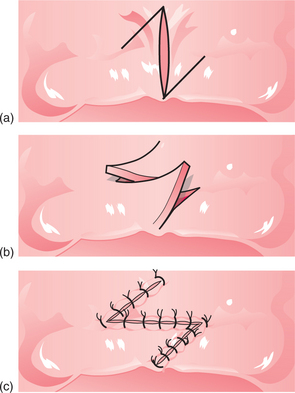

For the fraenectomy procedure (also described in Ch. 12) vertical incisions are made parallel to the fraenum, extending into the sulcus from the residual ridge to form a rhomboid-shaped wound (Fig. 11.7). The incisions are widest at the base of the labial sulcus. The insertion of the fraenum into the alveolar ridge is held with either a suture or a pair of toothed tissue forceps and the fraenum is dissected, leaving periosteum covering the surface of the bone. Interrupted sutures are inserted through the mucoperiosteal flap to achieve wound closure. A modification of this procedure incorporates a Z-plasty, to preserve sulcus depth (Fig. 11.8). However, the Z-plasty can be technically more difficult than the fraenectomy technique described above.

Fibrous enlargement of the maxillary tuberosity

Ideally, the maxillary tuberosities are firm for denture support. If they are flabby and mobile, the soft tissues of the tuberosities may displace during impression-taking for a new denture, making denture construction difficult. Fibrous enlargement of a maxillary tuberosity may be reduced (Fig. 11.9) by making two incisions along the crest of the alveolar ridge to form an ellipse, angled towards the centre of the ridge down to bone. A t/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses