11

Orthodontic Examination and Decision Making for the Family Dentist

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to use the basic principles and clinical examples (potentiality) given in the preceding chapters to help individual dentists make decisions about malocclusions encountered in their patients (actuality). Learning is the actualization of potentiality. Learning is self-activity, a process of self-development (Mayer 1928). The teacher is an extrinsic proximate agent. Knowledge is acquired in two ways: (1) when natural reason itself comes to knowledge of the unknown which is discovery, and (2) when a teacher leads another to knowledge of the unknown in the same way he, as the learner, would lead himself (Mayer 1928).

Benjamin Bloom (1976), a leader in educational research, created mastery learning as a method of teaching that enables most students in a class room to reach high levels of achievement. The basic premise of mastery learning is that a student must master one learning task before learning the next task:

What any person in the world can learn, almost all persons can learn if provided with appropriate prior and current conditions of learning. This generalization does not appear to apply to the 2% or 3% of individuals who have severe emotional and physical difficulties that impair their learning. At the other extreme there are about 1% or 2% of individuals who appear to learn in such unusually capable ways that they may be exceptions to the theory. At this stage of the research it applies most clearly to the middle 95% of a school population.

The middle 95% of school students become very similar in terms of their measured achievement, learning ability, rate of learning, and motivation for further learning when provided with favorable learning conditions. One example of such favorable learning conditions is mastery learning where the students are helped to master each learning unit before proceeding to a more advanced learning task. In general, the average student taught under mastery-learning procedures achieves at a level above 85% of students taught under conventional instructional conditions. An even more extreme result has been obtained when tutoring was used as the primary method on instruction. Under tutoring, the average student performs better than 98% of students taught by conventional group instruction, even though both groups of students performed at similar levels in terms of relevant aptitude and achievement before the instruction began

(Bloom 1976).

On the basis of his extensive educational research, Bloom (1976, 1985) determined that favorable learning conditions include (1) cues, instruction about what is to be learned, and directions for what the learner must do in the learning process; (2) reinforcement, the use of approval or disapproval by a teacher to help a student learn; (3) participation, the learner must do something with the cues to actually learn; and (4) feedback/correctives, a teacher adapting the cues, the use of reinforcement, and the amount of participation or practice to the characteristics and needs of an individual learner.

An American Dental Education Association Commission (2006) presented educational strategies for developing problem solving, critical thinking, and self-directed learning in dentists. The Commission recommended giving students opportunities to use the following reflective judgment process to analyze the diagnosis and treatment of a dental patient: (1) identify the facts and issues in a problem, (2) identify and explore causal factors, (3) retrieve and assess knowledge needed to appraise response and guide actions, (4) compare the strengths and limitations of options, (5) implement the best option to solve the problem, (6) monitor treatment and outcomes and modify treatment as needed, and (7) appraise the outcomes of treatment, positively and negatively. Following these steps routinely with patients will help a novice acquire the skills observed in experts.

Orthodontic Screening

The orthodontic screening form shown in Figure 11.1 is completed at a chair-side examination of a patient. The diagnostic information gathered on the form is used to make a decision concerning the orthodontic treatment disposition of the patient. Three dispositions are listed on the form:

1. The patient has normal occlusion (normal dental and skeletal relationships) for the primary, mixed, or permanent dentition (circle the letter Q). The decision made for these patients is to monitor the patient’s occlusion at future appointments.

2. The patient has a significant malocclusion problem requiring comprehensive orthodontic treatment (circle the letter R). The decisions made for these patients are: (a) inform the patient or parents of minors that the patient has a significant malocclusion, and (b) refer the patient to an orthodontist.

3. The patient has a malocclusion problem not requiring comprehensive orthodontic treatment, or a young patient has a condition requiring either interceptive orthodontic treatment or intervention to prevent the development of a malocclusion (circle the letter S). The decisions required for these patients are: (a) inform the patient or parents of minors that the patient has a malocclusion that needs to be treated, or that the patient needs a preventive interceptive treatment, and (b) that you can either deliver the required treatment, or refer the patient to a pediatric dentist or orthodontist.

Figure 11.1. Orthodontic screening form.

Guidelines for Orthodontic Decision Making

Guidelines for orthodontic decision making are shown in Figure 11.2. These guidelines help a family dentist to differentiate malocclusions requiring comprehensive orthodontic treatment from malocclusion problems that can be treated by the family dentist. Guidelines for factors such as crowding, spacing, overbite, and overjet, anterior crossbite, posterior crossbite, and space regaining are given in Figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2. Guidelines for orthodontic decision making.

When an upper or lower permanent first molar tips forward after the premature loss of a primary molar, the molar occlusion in that quadrant of the arch will be Class II in the upper arch or Class III in the lower arch. In these patients, family dentists can correct the problem in those patients who have a Class I relation in the molars on the unaffected side of the arch and an otherwise normal occlusion.

In the mixed-dentition patient, premature asymmetric loss of primary molars should be followed by the delivery of a space maintainer to avoid the complications associated with asymmetry and impaction of nonerupted teeth. This recommendation is appropriate for patients with Class I, Class II, and Class III malocclusions. In the permanent dentition patient, the loss of a tooth should be followed by appropriate intervention (implant, bridge, removable partial denture) to avoid the development of a malocclusion.

Differentiating Class I Problems Suitable for Limited Orthodontic Treatment from More Complex Class I Problems

Pretreatment Records

The pretreatment records of patients with Class I malocclusions are presented with additional diagnostic information in the text. The challenge to the reader is to (1) identify the malocclusion problem, (2) assess the difficulty of the problem (s), (3) differentiate the Class I limited problems from those requiring more extensive treatment, and (4) develop a treatment and appliance plan for the patient suitable for limited orthodontic treatment.

Patient 1.

An 8-year 7-month-old boy presented with a chief concern that his upper incisors were in crossbite. In centric occlusion all four of his upper incisors were in crossbite (Figs. 11.3 to 11.6). In centric occlusion his permanent first molars and canines were in Super Class I occlusion (Figs. 11.4 and 11.5). When asked if he could move his lower incisors back into contact with his upper incisors (to determine the existence of an anteroposterior shift from centric relation to centric occlusion), he produced the centric relation occlusion shown in Figures 11.7 to 11.10. In centric relation, only his upper left central incisor was in crossbite and his molars were Class I. He had a 3.5-mm functional shift between centric relation and centric occlusion (Figs. 11.7 to 11.10). His upper left central incisor in crossbite was inclined (tipped) lingually. His lower left central incisor was rotated and had labial gingival recession as a result of its traumatic occlusion. Adequate arch length was available to move the upper left central incisor into the line of arch. Overbite and overjet measured in centric relation were 37% and 1.3 mm, respectively.

Figure 11.3. Front view of a patient in centric occlusion with an anterior crossbite of the upper right lateral incisor and both upper central incisors. Note the gingival recession on the labial root surface of the lower left central incisor.

Figure 11.4. Right lateral view of the anterior crossbite in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.5. Left lateral view of the anterior crossbite in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.6. Left lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canine and molar relations as Class III.

Figure 11.7. Front view of the patient in centric relation. Only the upper left central incisor is in crossbite. Note the traumatic occlusion involving the upper and lower left central incisors.

Figure 11.8. Right lateral view of the patient’s occlusion in centric relation.

Figure 11.9. Left lateral view of the occlusion in centric relation.

Figure 11.10. Left lateral view of the casts in centric relation showing canine and molar relations as Class I.

Patient 2.

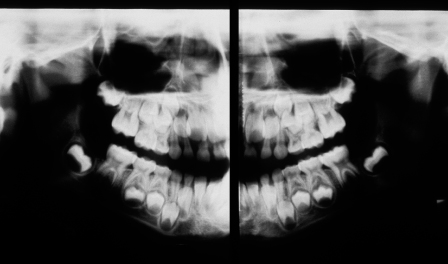

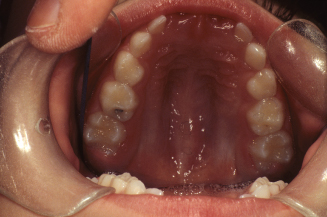

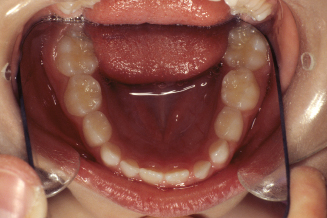

A 13-year 9-month-old boy in the permanent dentition presented with the chief concern that his upper lateral incisors were in anterior crossbite (Figs. 11.11 to 11.18). His first molars and canines were Class I (Figs. 11.14 and 11.15). He had 4.4 mm of upper arch crowding, normal upper intercanine width, an upper intermolar width of 49.1 mm that was 2 standard deviations narrower than the male mean, a lower intercanine width of 28.6 mm that was one standard deviation narrower than the norm, and a lower intermolar width of 50.1 mm that was 2 standard deviations narrower than the norm. The center of the incisal edges of the upper lateral incisors were about 5 mm lingual to the upper line of arch. He had an overbite of 20% and an overjet of 2 mm. There was no evidence of an anteroposterior functional shift.

Figure 11.11. Front view of a patient in centric occlusion with the upper lateral incisors in crossbite.

Figure 11.12. Panoramic radiograph of the teeth.

Figure 11.13. Right lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.14. Right lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canines and molars in Class I.

Figure 11.15. Left lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.16. Left lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canines and molars in Class I.

Figure 11.17. Occlusal view of the upper teeth.

Figure 11.18. Occlusal view of the lower teeth.

Patient 3.

A 6-year 4-month-old girl presented with a unilateral posterior crossbite diagnosed by her family dentist. The crossbite was on her right side and she had an associated lateral shift of 2 mm from centric relation to centric occlusion (Figs. 11.19 to 11.26). The panoramic radiograph depicts her early mixed-dentition stage of development (Fig. 11.20). Her maxillary intermolar width was 46.1 mm and that was normal for the mixed dentition (Table 8.2). Her mandibular intermolar width was 49.1 mm, 1 standard deviation wider than normal. She needed to widen her upper arch to 49.1 mm and an additional 1.2 mm for adequate buccal overjet for a total of 4.2 mm. Her Angle notation was E, E, I, SI. Overbite and overjet were not measurable because of the missing upper incisors.

Figure 11.19. Front view of a patient with a unilateral posterior crossbite on the right side. The upper primary incisors have exfoliated.

Figure 11.20. Panoramic radiograph of the patient.

Figure 11.21. Right lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.22. Right lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canines and molars in Class I.

Figure 11.23. Left lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.24. Left lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing the canines in Class I and the first permanent molars in Super Class I.

Figure 11.25. Occlusal view of the upper teeth.

Figure 11.26. Occlusal view of the lower teeth.

Patient 4.

A 6-year 2-month-old boy presented with anterior and unilateral crossbites (Figs. 11.27 to 11.34). He was in the early mixed dentition with only three erupted permanent teeth, the lower central incisors and lower left first molar. His upper right primary central and lateral incisors were in edge to edge (zero overbite and overjet) with the lower incisors. His upper left primary central and lateral incisors and canines were in anterior crossbite. The patient had an anteroposterior functional shift of about 1 to 2 mm. His upper left primary molars were in crossbite (Figs. 11.31 and 11.32). He had a lateral functional shift of about 2 mm toward the left side. His upper intermolar width (between I and J) was 41.4 mm, within normal limits (Table 8.3). His lower intermolar width was 43.4, 1 standard deviation wider than normal. The etiology of his posterior crossbite was a wider-than-normal lower posterior arch width. The intermolar width difference was −2.0 mm. Adding the difference observed between the mean norms for upper and lower intermolar widths (2.7 mm, Table 8.3), gives a goal for expansion of 4.7 mm. His Angle notation was I, I, E, SI. The anterior crossbite involved upper primary incisors that had partially resorbed roots.

Figure 11.27. Frontal view of the teeth in centric occlusion with the incisors in anterior crossbite and a unilateral left posterior crossbite.

Figure 11.28. Frontal view of the casts in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.29. Right lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.30. Right lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing Class I relationships in the primary canines and molars.

Figure 11.31. Left lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.32. Left lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canines in Class I and the primary molars in Super Class I.

Figure 11.33. Occlusal view of the upper teeth.

Figure 11.34. Occlusal view of the lower teeth.

Patient 5.

A 15-year 9-month-old adolescent girl presented with a 2.5 mm diastema between her upper central incisors (Figs. 11.35 to 11.42). She had an overjet of 2.4 mm and overbite of 44.9%. The Bolton overall ratio predicted 4 mm of mandibular excess, and the anterior ratio predicted 1 mm of mandibular excess. Her lower incisors were mildly crowded, less than 1 mm.

Figure 11.35. Front view of the teeth in centric occlusion. The patient was concerned about the diastema between her upper central incisors.

Figure 11.36. Right lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.37. Right lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canines and molars in Class I.

Figure 11.38. Left lateral view of the teeth in centric occlusion.

Figure 11.39. Left lateral view of the casts in centric occlusion showing canines and molars in Class I.

Figure 11.40. Occlusal view of the upper teeth.

Figure 11.41. Occlusal view of the upper cast.

Figure 11.42. Occlusal view of the lower teeth.

Patient 6.

A 12-year 11-month-old adolescent girl presented with a 6.3 mm diastema between her upper central incisors (Figs. 11.43 to 11.50). She had an overjet of 3.6 mm and overbite of 44%. The Bolton overall ratio predicted a good fit f/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses