Mucosal, oral and cutaneous disorders

Key Points

• Rashes can be genetic or acquired (infective, autoimmune, inflammatory, allergic)

• Epidermolysis bullosa and pemphigus can be life-threatening

Skin Diseases

The common and more important skin diseases only are discussed here.

Acne

General aspects

Acne is a common skin disorder in which hair follicles become blocked with oil and hypertrophied epithelium; it is characterized by clogged pores and pimples. More than 4 out of 5 people, particularly adolescent males, develop acne. Several factors – including hormones, bacteria, medications such as corticosteroids, heredity and stress – play a role. Many adult women experience mild to moderate acne due to hormonal changes associated with menstrual cycles, starting or stopping oral contraceptives, or pregnancy.

Clinical features

Pimples appear as hair follicles and become plugged with oil and dead skin cells, causing the follicle wall to bulge and produce a ‘whitehead’. If the pore stays open and traps dirt, the plug surface oxidises and darkens, causing a ‘blackhead’. Blockages and inflammation deep inside hair follicles can produce scarring and cysts. Acne is rarely serious but it often causes emotional distress.

General management

Effective lotions generally contain benzoyl peroxide or azelaic acid. Topical erythromycin and clindamycin are effective treatments for inflamed lesions. Systemic acne treatment should start with antimicrobials (tetracyclines or erythromycin). Options for scarring cystic acne or acne that fails to respond to other treatments are, in women, cyproterone acetate or isotretinoin (vitamin A analogue, only prescribable by consultant dermatologists). For men, only isotretinoin is available. Oral contraceptives, including a combination of norgestimate and ethinylestradiol, can improve acne in women. Maternal use of vitamin A congeners must be avoided since birth defects similar to those in Di George syndrome can result – the fetal isotretinoin syndrome.

Dermabrasion (removing the top skin layers with a rapidly rotating wire brush) may help more severe scarring. Laser resurfacing can achieve the same effect.

Cancer

General aspects

The three major types of skin cancer, all on the increase, are (see also Ch. 22):

All are on the increase; nearly half of all men over 65 years will develop a skin cancer. Risk factors are shown in Box 11.1.

Clinical features and general management

Skin cancer develops mainly on areas of sun-exposed skin: the scalp, face, lips, ears, neck, chest, arms and hands, and on the legs in women. BCC is superficial and highly treatable, especially if found early. It appears as a pearly or waxy lump on the face, ears or neck, or a flat, flesh-coloured or brown scar-like lesion on the chest or back, typically in persons after middle age, but responds to excision. In Gorlin syndrome, BCC can start to form in childhood.

SCC is superficial, slow-growing and highly treatable, especially if found early. It presents as a firm, red nodule on the face, lip, ears, neck, hands or arms, or a flat lesion with a scaly, crusted surface on the face, ears, neck, hands or arms. It usually responds to wide excision.

Melanoma has the greatest potential to spread and may be fatal. It typically appears as: a large brownish spot with darker speckles, anywhere; a simple mole anywhere that changes in colour or size or consistency, or that bleeds or exhibits new growth; a small lesion with an irregular border and red, white, blue or blue–black spots on the trunk or limbs; shiny, firm, dome-shaped nodules anywhere; dark lesions on palms, soles, tips of fingers and toes, or on mucous membranes; or a red flat lesion (amelanotic melanoma). Malignant melanomas can also form in the retina or, rarely, even in areas protected from sunlight such as the mouth.

Treatment of melanoma is usually excision, and if the tumour is superficial (Breslow depth<1.5 mm) the prognosis is excellent at 90% 5-year survival. The prognosis of malignant melanoma is usually poor as a consequence of late diagnosis and rapid spread: survival averages only 2 years.

Dental aspects

Dentists are a risk group for skin cancers (from excess vacational sun exposure!).

Eczema

General aspects

Eczema is a term describing a range of persistent skin conditions that include dryness and recurring rashes characterized by redness, itching, crusting, flaking, blistering, cracking, oozing or bleeding.

Clinical features

General management

Patch-testing, raised serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), eosinophilia, radioallergosorbent test (RAST) or paper radioimmunosorbent test (PRIST; Ch. 17) may be diagnostically helpful. There is no known cure. Treatments, which aim to control symptoms, reduce inflammation and relieve itching, include topical emollients, corticosteroids, or calcineurin inhibitors. Ciclosporin, azathioprine or methotrexate may rarely be needed.

Psoriasis

General aspects

Psoriasis is a common chronic skin disease characterized by scaling and inflammation. It has a strong genetic background with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6 and HLA-DR7. T cells trigger inflammation, and excessive skin cell reproduction underlies the pathogenesis. There are sometimes associations with stress and alcoholism.

Clinical features

Psoriasis causes thick pruritic erythematous plaques covered with silvery scales (Fig. 11.3), predominantly on scalp, elbows and knees, lower back, face, palms, and soles of feet, and ‘ice-pick’ pitting or onycholysis of fingernails and toenails (Fig. 11.4). About 15% have joint inflammation (psoriatic arthropathy).

General management

Treatment of psoriasis initially is with topical agents – corticosteroids, vitamin D3, vitamin A analogues (retinoids), coal tar or dithranol (anthralin). Failing this, light (phototherapy) is used. Sunlight often helps but more controlled artificial light treatment may be used in mild psoriasis (ultraviolet B phototherapy), or psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy in more severe or extensive psoriasis.

Severe cases of psoriasis may need systemic treatment with methotrexate, ciclosporin or retinoids.

Dental aspects

Local anaesthesia (LA) is safe. Conscious sedation (CS) can be given if required.

Oral lesions, such as white or reddish mucosal plaques, are rare. There may be a higher prevalence of erythema migrans and fissured tongue, particularly in pustular psoriasis. The temporomandibular joint is involved in up to 60% of patients with psoriatic arthropathy.

Oral complications of the treatment of psoriasis, such as gingival swelling from ciclosporin, or ulceration from methotrexate, may be seen.

Acquired Mucocutaneous Disorders

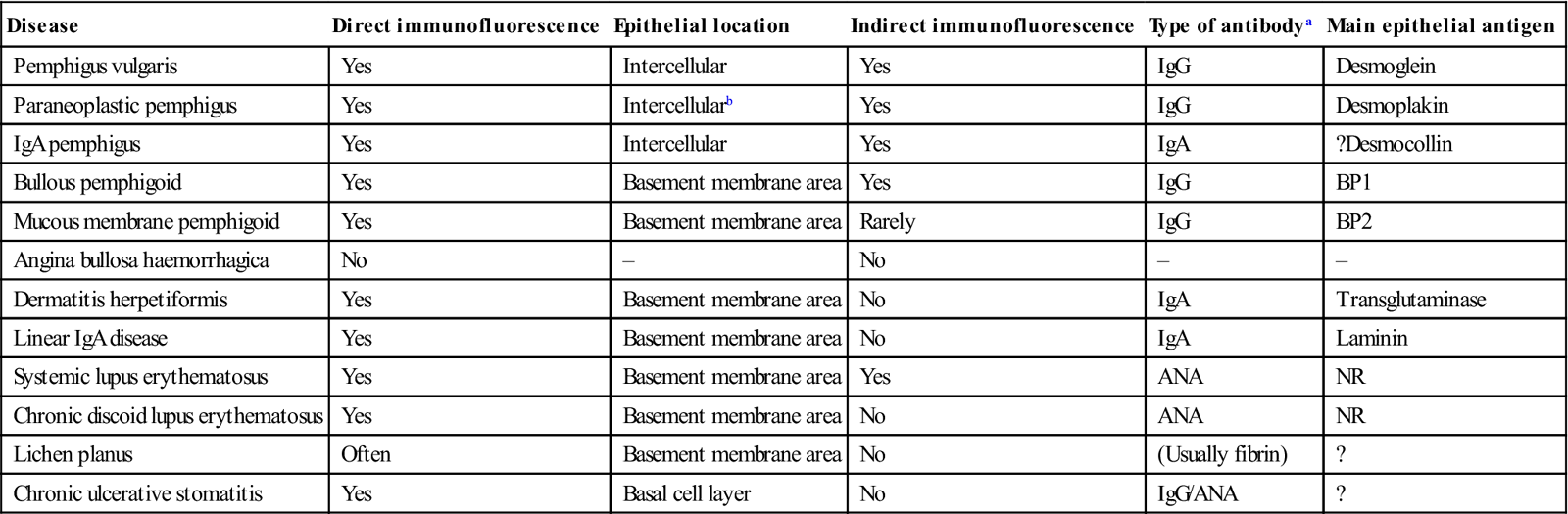

Several mucocutaneous diseases can involve the mouth or may influence dental treatment. The most common is lichen planus. The most serious are pemphigus (which is potentially fatal), erythema multiforme and mucous membrane pemphigoid (which may involve other mucosae). Oral lesions herald some mucocutaneous diseases or may be the main manifestation. Immunostaining can often help the diagnosis (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1

Immunostaining in skin and oral mucosal diseases

< ?comst?>

| Disease | Direct immunofluorescence | Epithelial location | Indirect immunofluorescence | Type of antibodya | Main epithelial antigen |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Yes | Intercellular | Yes | IgG | Desmoglein |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | Yes | Intercellularb | Yes | IgG | Desmoplakin |

| IgA pemphigus | Yes | Intercellular | Yes | IgA | ?Desmocollin |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Yes | Basement membrane area | Yes | IgG | BP1 |

| Mucous membrane pemphigoid | Yes | Basement membrane area | Rarely | IgG | BP2 |

| Angina bullosa haemorrhagica | No | – | No | – | – |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Yes | Basement membrane area | No | IgA | Transglutaminase |

| Linear IgA disease | Yes | Basement membrane area | No | IgA | Laminin |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Yes | Basement membrane area | Yes | ANA | NR |

| Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus | Yes | Basement membrane area | No | ANA | NR |

| Lichen planus | Often | Basement membrane area | No | (Usually fibrin) | ? |

| Chronic ulcerative stomatitis | Yes | Basal cell layer | No | IgG/ANA | ? |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

ANA=antinuclear antibody; BP=bullous pemphigoid; Ig=immunoglobulin; NR=not relevant.

Many of the mucocutaneous diseases are treated with corticosteroids (topically or systemically), which may, if used for prolonged periods, cause adrenocortical suppression (Ch. 6).

Lichen Planus

General aspects

Lichen planus (LP) is a common skin and mucosal disease. The immunopathogenesis includes a dense T-lymphocyte infiltrate, to an unidentified provoking antigen.

Lesions clinically and histologically similar or identical to LP (lichenoid lesions) can be related to dental restorations, particularly amalgam and drugs, especially to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gold, antimalarials and beta-blockers. Reported associations of oral LP with diabetes mellitus and hypertension have not been confirmed, and the so-called Grinspan syndrome of LP, diabetes mellitus and hypertension is probably related to drug treatment. Similar lesions may be reactions to chemicals, such as photographic developing solutions, graft-versus-host disease (Ch. 35), chronic liver disease and virus infections – hepatitis C or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Approximately 1% of cases of oral LP may develop malignant change after 10 years.

Clinical features

Skin lesions are usually small polygonal purplish or violaceous itchy papules, particularly affecting the flexor surfaces of the wrist (Fig. 11.5), and also elsewhere such as the shins (Fig. 11.6) or periumbilically, but rarely, if ever, on the face. Examination with a lens may show a fine lacy white network of striae (Wickham striae) on these papules (Fig. 11.7). Mouth and genital lesions in LP include white striae, papules, plaques, or red atrophic areas or erosions (Fig. 11.8). The nails or hair may be affected (Fig. 11.9).

General management

A drug history should be taken in order to exclude possible reactions. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, a biopsy is needed, particularly to differentiate LP from lupus erythematosus, chronic ulcerative stomatitis or keratoses. Topical corticosteroids or tacrolimus can be useful to control symptomatic LP, especially severe erosive lesions. Aloe vera reportedly gives effective symptomatic relief.

Exceptionally severe LP sometimes responds only to systemic corticosteroids. Other drugs, such as vitamin A analogues (etretinate), dapsone, ciclosporin or alefacept, are used only rarely.

Dental aspects

Oral lesions in LP can persist for years, although the skin lesions frequently resolve within a few months. Oral lesions characteristically are bilateral and sometimes strikingly symmetrical; they affect particularly the posterior buccal mucosa but may also involve the tongue, gingivae or other sites. Gingival lesions are usually atrophic and red (‘desquamative gingivitis’).

Replacement of amalgam with non-metallic alternatives may sometimes cause lesions to resolve, but relapse is possible. LA is safe. CS can be given if required.

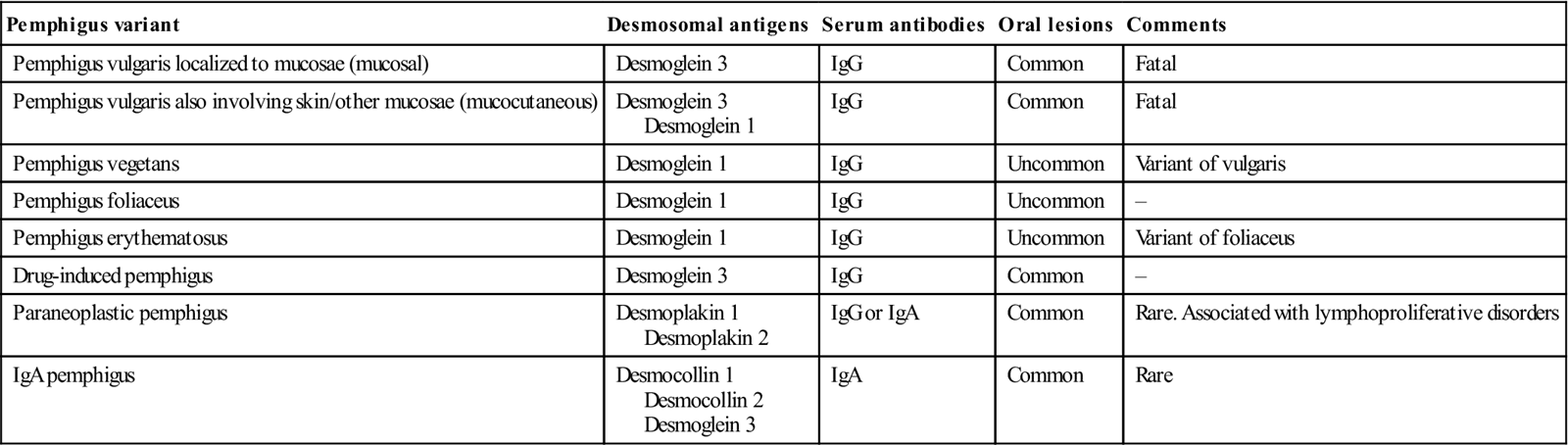

Pemphigus

Pemphigus is a potentially fatal autoimmune reaction against proteins, usually within the stratified squamous epithelium; it is characterized by widespread formation of skin vesicles and bullae. The mouth is frequently the first site of attack. Variants include those listed in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2

< ?comst?>

| Pemphigus variant | Desmosomal antigens | Serum antibodies | Oral lesions | Comments |

| Pemphigus vulgaris localized to mucosae (mucosal) | Desmoglein 3 | IgG | Common | Fatal |

| Pemphigus vulgaris also involving skin/other mucosae (mucocutaneous) | Desmoglein 3 Desmoglein 1 |

IgG | Common | Fatal |

| Pemphigus vegetans | Desmoglein 1 | IgG | Uncommon | Variant of vulgaris |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Desmoglein 1 | IgG | Uncommon | – |

| Pemphigus erythematosus | Desmoglein 1 | IgG | Uncommon | Variant of foliaceus |

| Drug-induced pemphigus | Desmoglein 3 | IgG | Common | – |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | Desmoplakin 1 Desmoplakin 2 |

IgG or IgA | Common | Rare. Associated with lymphoproliferative disorders |

| IgA pemphigus | Desmocollin 1 Desmocollin 2 Desmoglein 3 |

IgA | Common | Rare |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Pemphigus vulgaris

General aspects

Pemphigus vulgaris is an uncommon disease, which mainly affects middle-aged women. Pemphigus may occasionally be associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, or thymoma and myasthenia gravis. Rarely, it is induced by a drug such as rifampicin, penicillamine or captopril. The main immunological finding is circulating antibodies to desmogleins of intercellular attachments (desmosomes) of epithelial cells of stratified squamous epithelia. These IgG antibodies, and complement components, are deposited (and can also be localized by immunostaining) around the epithelial cells, and result in loss of adherence of the cells to one another (acantholysis). Pemphigus is characterized by widespread formation of intraepithelial vesicles and bullae.

Clinical features

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by thin-roofed vesicles or bullae, followed by ulceration (Fig. 11.10). It frequently appears in the mouth first. Stroking the skin or mucosa with a finger may induce vesicle formation in an apparently unaffected area or cause a bulla to extend (Nikolsky sign). If untreated, pemphigus vulgaris is usually fatal, as a result of extensive skin and mucosal damage leading to fluid and electrolyte loss, and often infection.

General management

Rapid and precise diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris is essential since acute cases need immediate immunosuppressive treatment. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy. The specimen should be halved to enable both light and immunofluorescent microscopy to be carried out. Light microscopy on a paraffin section is usually distinctive and shows suprabasal cleft formation and intraepithelial vesicles containing free-floating acantholytic cells. Immunofluorescence examination shows IgG and C3 deposits intercellularly. It can be carried out by the direct method using fluorescein-conjugated anti-human IgG and anti-complement (C3) sera on the frozen specimen or on exfoliated cells. In the indirect method, the patient’s serum is incubated with normal animal mucosa, which is then labelled with fluorescein-conjugated antihuman globulin (see Table 11.1). Antibodies to desmoglein 1 may be found in pemphigus vulgaris with cutaneous lesions, or in pemphigus foliaceus; antibodies to desmoglein 3 may herald oral involvement in pemphigus vulgaris.

The usual treatment of pemphigus vulgaris is with high doses of systemic corticosteroids plus a steroid-sparing agent such as azathioprine. Gold may sometimes be used. Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil also appear to be effective. With current methods of treatment, the mortality may be reduced to about 8% but is often a complication of immunosuppressive treatment. Long-term remission has been reported but many require prolonged therapy.

Dental aspects

LA and CS can be given as required. Orofacial manifestations are as described above. However, blisters are so fragile as rarely to be seen intact in the mouth. They leave painful erosions.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid

General aspects

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is a group of subepithelial immune blistering diseases with autoantibodies directed to different epithelial basement membrane proteins. Oral pemphigoid-like lesions have occasionally been reported in association with internal cancers or the use of certain drugs, such as penicillamine. Autoantibodies against basement membrane proteins cause loss of attachment of the epithelium to the connective tissue and blister formation. The common variant of mucous membrane pemphigoid has antibodies against bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP2) but the types that mainly affect the mouth have antibodies against integrin or epiligrin. Serum autoantibodies are demonstrable by conventional techniques in relatively few patients.

Clinical features

Mucous membrane pemphigoid predominantly affects women between 50 and 70 years of age. Intact vesicles or bullae are frequently visible. Sometimes the blisters fill with blood and then must be distinguished from generalized or localized oral purpura. The gingivae may be particularly affected and pemphigoid is an important cause of so-called ‘desquamative gingivitis’. Progress is typically indolent and lesions may remain restricted to one site, such as the mouth, for several years or possibly never develop elsewhere, depending on the type.

Scarring after healing of the bullae is a serious complication in sites such as the eyes, larynx, oesophagus or genitalia. Ocular involvement is the most common dangerous manifestation since it can impair or destroy sight (Fig. 11.11). Laryngeal or oesophageal stenosis secondary to scarring is also possible.

General management

The diagnosis of pemphigoid must be confirmed by biopsy. The section should be halved and a frozen section tested f/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses