Chapter 11

Medical Emergencies in the Dental Emergency Clinic – Principles of Management

Introduction

The commonest medical emergencies seen in the dental emergency clinic are faints. Hypoglycaemia, asthma, anaphylaxis, angina and seizures may also be seen but are less common. All members of the dental team need to be aware of what their role would be in the event of a medical emergency and should be trained appropriately with regular practise sessions.

A thorough history is always important. If a medical condition is identified and medication is normally taken, a check should always be made to ensure that the medication has been taken as usual and its usual level of efficacy.

Contents of the emergency drug box

Medical emergencies may require equipment, drugs or both in order to manage them effectively and all must be available to use if necessary. Emergency telephone numbers should be known by all members of the team.

Drugs to be included in the emergency drug box are summarised in Table 11.1. The list is based on that given in a Resuscitation Council (UK) document on Medical Emergencies and Resuscitation in Dentistry, the reference to which is given at the end of the chapter.

Table 11.1 Contents of the emergency drug box and routes of administration.

| Drug | Route of administration |

| Oxygen | Inhalation |

| Glyceryl trinitrate spray (400 μg per actuation) | Sublingual |

| Dispersible aspirin (300 mg) | Oral (chewed) |

| Adrenaline injection (1:1000, 1 mg/mL) | Intramuscular |

| Salbutamol aerosol inhaler (100 μg per actuation) | Inhalation |

| Glucagon injection (1 mg) | Intramuscular/subcutaneous |

| Oral glucose solution/gel (GlucoGel®)a | Oral |

| Midazolam 10 mg or 5 mg/mL (buccal or intra-nasal) | Infiltration/inhalation |

| aAlternatives: Two teaspoons of sugar/three sugar lumps 200 mL milk Non-diet Coca-cola® 90 mL Non-diet Lucozade® 50 mL If necessary, this can be repeated at 10–15 minutes. |

|

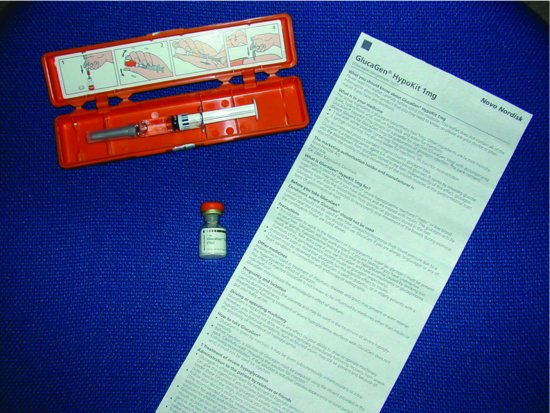

The Resuscitation Council (UK) recommends that such kits should be standardised throughout the United Kingdom. Drugs ideally should be carried in a pre-filled syringe or kit (Figure 11.1). All drugs should be stored together and ideally in a purpose-designed container.

Figure 11.1 A ‘Glucagon Kit’ with water for dilution drawn up and powder for reconstitution.

The optimum route for delivery of emergency drugs is usually the intravenous route but dentists are often inexperienced with this route of delivery. As a result of this, formulations have now been developed that allow for other routes to be used, which are much quicker and user-friendly. The intravenous route for emergency drugs is no longer recommended for dental practitioners. Oxygen should always be available, deliverable at adequate flow rates (up to 15 L/min) via a non-rebreathe mask (Figure 11.2). The non-rebreathe mask has a one-way valve that means that oxygen delivery is maximised and inhalation of expired carbon dioxide is minimised.

Figure 11.2 Oxygen being administered via a non-rebreathe mask. Note the reservoir bag and the D type oxygen cylinder.

Equipment for use in medical emergencies

The Resuscitation Council (UK) have recommended as a minimum the equipment shown in Box 11.1. Named individuals should be nominated to check equipment and this should be carried out at least weekly and the process should be audited.

Box 11.1 Minimum equipment for medical emergency management

- Portable oxygen cylinder (D size) with a flow meter and pressure reduction valve attached to a non-rebreathe mask (Figure 11.2)

- Oxygen face mask with tubing

- Oropharyngeal airways – sizes 1, 2, 3 and 4 (Figure 11.3)

- Pocket mask with port for oxygen

- Bag and mask apparatus (1 L bag capacity) with oxygen reservoir

- Well-fitting face masks

- Portable suction

- Single-use sterile syringes and needles

- ‘Spacer’ device for inhaled bronchodilators

- Blood glucose measurement device

- Automated external defibrillator (AED) – see Figure 11.5

Source: Adapted from Resuscitation Council (UK).

Figure 11.3 Various sizes of oro-pharyngeal airway.

It is a public expectation that AEDs (see later) should be available in the healthcare environment and dentistry is not considered an exception. All emergency medical equipment should be latex free and single use wherever possible.

The ‘ABCDE’ approach to an emergency patient

Medical emergencies can often be prevented by early recognition. An abnormal patient colour, pulse rate or breathing can signal some impending emergencies.

It is important to have a systematic approach to an acutely ill patient and to remain calm. The principles are summarised in the ‘ABCDE’ approach (Box 11.2).

Box 11.2 The ABCDE approach to an emergency patient

A: Airway

B: Breathing

C: Circulation

D: Disability (or neurological status)

E: Exposure (in dental practice, to facilitate placement of AED paddles) or appropriately exposing parts to be examined, for example to observe a rash

Ensure that the environment is safe. It is important to call for help at a very early stage. Continuous reappraisal of the patient’s condition should be carried out and the airway must always be the starting point for this. Without appropriate oxygen delivery, all other management steps will be ultimately futile. It is important to assess the success or otherwise of manoeuvres or treatments given, bearing in mind that treatments may take time to work.

Talking to the patient may give important information about the problem (for example, the/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses