11

HIV/AIDS and Related Conditions

I. Background and Rationale

Description of Disease

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the etiological agent for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). HIV is a retrovirus in the Lentivirus group.

Definition

The 2008 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of HIV and AIDS for public surveillance1 is based on the laboratory evidence of HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection, the CD4 cell count, and the presence of AIDS-defining conditions outlined in the 1993 case definition.2 See Table 11.1. Patients with laboratory-confirmed HIV infection may be in one of four HIV infection stages: Stage 1, 2, 3/AIDS, or unknown.

Table 11.1. The 2008 Surveillance Case Definition for HIV Infection among Adults and Adolescents (Aged ≥13 Years), United States, 20081

| Stage | Laboratory Evidence | Clinical Evidence |

| Stage 1 | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of ≥500 cells/µL or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of ≥29 | None required (but no AIDS-defining conditions) |

| Stage 2 | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 200–499 cells/µL or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of 14–28 | None required (but no AIDS-defining conditions) |

| Stage 3 (AIDS) | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of <200 cells/µL or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of <14 | or documentation of an AIDS-defining condition (with laboratory confirmation of HIV infection)b |

| Stage unknowna | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and no information on CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or percentage | and no information on the presence of AIDS-defining conditions |

Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection from either (1) positive result from an HIV antibody screening test (e.g., reactive enzyme immunoassay [EIA]) confirmed by a positive result from a supplemental HIV antibody test (e.g., Western blot or indirect immunofluorescence assay test) or (2) positive result or report of a detectable quantity (i.e., within the established limits of the laboratory test) from any of the following HIV virological (i.e., non-antibody) tests: HIV nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) detection test (e.g., polymerase chain reaction [PCR]); HIV p24 antigen test, including neutralization assay; HIV isolation (viral culture).

a Every effort should be made to report CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts or percentages and the presence of AIDS-defining conditions at the time of diagnosis.

b Documentation of an AIDS-defining condition supersedes a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of ≥200 cells/µL and a CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of ≥14. Definitive diagnostic methods for these conditions are available in Appendix C of the 1993 revised HIV classification system and the expanded AIDS case definition and from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System.

- Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs

- Candidiasis, esophageal

- Cervical cancer, invasive

- Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

- Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (greater than 1 month’s duration)

- Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes)

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)

- Encephalopathy, HIV related

- Herpes simplex: chronic ulcer(s) (greater than 1 month’s duration), or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis

- Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (greater than 1 month’s duration)

- Kaposi’s sarcoma

- Lymphoma, Burkitt’s (or equivalent term)

- Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term)

- Lymphoma, primary, of the brain

- Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis, any site (pulmonary or extrapulmonary)

- Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary

- Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

- Pneumonia, recurrent

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Salmonella septicemia, recurrent

- Toxoplasmosis of the brain

- Wasting syndrome due to HIV

Pathogenesis/Etiology

Once transmission of HIV occurs, the retrovirus enters human cells, particularly the CD4+ (T-helper) lymphocytes in the peripheral blood and undergoes replication. Additional HIV virus is created and returned to the circulation, ultimately destroying the lymphocyte in the process. CD4+ lymphocyte depletion results in compromise of the host cell-mediated immune response.

Primary or acute infection and seroconversion usually occur without the display of any signs or symptoms; however, a small number of patients may experience a viral syndrome similar to the flu. In the next 6 months, HIV-specific antibody responses can be detected by standard HIV antibody tests. During the clinically latent or asymptomatic period of months to years, viral replication continues but the patient experiences few or no symptoms of HIV disease. Without medical intervention, eventually viral replication overcomes the host immune response and CD4+ counts begin a progressive decline. The immune system deteriorates, and patients become increasingly susceptible to opportunistic infections such as oral candidiasis and the most common AIDS-defining condition, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). Death may ensue in 2–3 years following diagnosis with an AIDS-defining illness if medical care is not accessed or effective at halting disease progression.

Epidemiology

In June 1981, five previously healthy young men in Los Angeles, CA, with PCP, two of whom had died, were the first cases of HIV/AIDS reported in the world. Thirty years after this, the U.S. CDC reported that there are an estimated 33.3 million people living with HIV infection worldwide at the end of 20093:

- Prevalence: Estimated U.S. persons living with HIV infection at the end of June 2008 = 1,178,350, of which 21% are undiagnosed and unaware of their HIV infection.4

- Incidence: Estimated new infections in the United States each year = 56,300 people.

- Gender: Of persons living with HIV/AIDS at year end 2008, 72% were adolescent and adult men, 26% were adolescent and adult women, and 2% were children under age 13 years.

- Age: All ages are affected, but the most common age group for new HIV cases (15%) is 20–24 years.

- Race/ethnicity: New HIV cases are in African-Americans (52%), whites (28%), Hispanics (17%), and others (3%). African-American men and women are estimated to have an incidence rate seven times higher than for whites.

- Risk behavior: Transmission risks of new HIV cases diagnosed in 2009 are reported as male-to-male sexual contact (MSM) (57%), high-risk heterosexual contact (31%), injection drug use (IDU) (9%), and MSM and IDU (3%).4

- Perinatal HIV transmission, for example, from mother to child during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and breast-feeding, has declined dramatically to less than 2% of births from HIV-infected mothers, as a result of maternal HIV testing and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy and labor and delivery, and avoidance of breast-feeding.

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

- Primary medical care guidelines for persons initiating HIV care5 state that the review of systems should include questioning about common HIV-related oral conditions including thrush or oral ulceration and the physical examination should include a careful examination of the oropharynx for evidence of candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, mucosal Kaposi’s sarcoma, aphthous ulceration, and periodontal disease.

- For optimal preventive oral health care, the physician should recommend dental consultation once HIV infection has been diagnosed and sought promptly when orofacial manifestations of HIV or acute dental disease develops since an oral infection can become life threatening in the severely immune compromised patient. Oral health care should be planned with consideration of the patient’s medical status.

- The dentist’s oral screening exam and/or use of a rapid oral-based point-of-care HIV antibody test in the dental office may help to identify new HIV infections and facilitate patient access to medical care. Whenever the dental practitioner identifies HIV-associated oral lesions in a patient of unknown HIV status, the dentist should discuss the possibility of HIV infection with the patient. Applicable state law should be consulted regarding confidentiality and other obligations.

II. Medical Management

II. Medical Management

Identification

While many HIV-infected patients will be aware of their serostatus, some will be unknown to the dentist because they are asymptomatic, have no physical signs and are unaware that they are seropositive, or withhold that information. A history of AIDS or HIV seropositivity may be supplied by the patient, or HIV infection may be suspected on the basis of the medical history or physical examination.

Medical History

Affirmative responses to confidential medical and social history questions in the following areas will alert the dentist to the possible need for further inquiry:

- AIDS or HIV infection;

- recurring infections (i.e., oral, tuberculosis [TB], pulmonary, gastrointestinal, sexually transmitted diseases);

- history of IDU;

- blood transfusions (1979–1985);

- hemophilia;

- malignancies (e.g., Kaposi’s sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) known to be associated with HIV infection;

- symptoms associated with HIV infection such as night sweats, prolonged diarrhea, unexplained weight loss, and fever;

- history of viral hepatitis.

Further inquiry might include questions concerning the following:

- Unsafe sexual practices known to be associated with HIV transmission especially in high-risk populations (e.g., prostitutes, men who have sex with men, IDUs, hemophiliacs) or having multiple sexual partners.

- Association with persons who have certain infectious diseases (i.e., viral hepatitis, AIDS, TB, sexually transmitted diseases). If the response is affirmative, there must be follow-up questions to ascertain if the contact was such that HIV could have been transmitted.

- Rejection as a blood donor.

Physical Examination

The physical examination is important in identifying and monitoring orofacial conditions that may be associated with HIV infection.6

Examples include:

- candidiasis;

- hairy leukoplakia;

- oral warts;

- linear gingival erythema;

- ulcerative necrotizing gingivitis and periodontitis;

- prolonged, extensive, and/or frequently occurring herpes simplex infections;

- more severe and prolonged recurrent aphthous ulcers;

- salivary gland enlargement;

- Kaposi’s sarcoma;

- cervical lymphadenopathy.

If the history or physical examination suggests the possibility of undiagnosed HIV infection, the provider should coordinate care with the primary care physician for a complete medical evaluation and laboratory testing.

Laboratory Testing

HIV Antibody Tests

HIV testing and referral are recommended for patients whose medical history or oral examination reveals the possibility of HIV infection. Early HIV detection and access to HIV medical care and ART can improve the quality and prolong the life span of the patient, as well as help to prevent future virus transmission.

To aid in HIV prevention efforts, the CDC revised its guidance to make HIV antibody testing routine in all health-care settings under general consent for medical care, unless the patient declines (opt-out screening), with prevention counseling no longer required7:

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme immunoassay (EIA). They are 99% sensitive but generate a number of false positives. They are used for rapid antibody screening tests and as the first test in the conventional test sequence.

- The more specific Western blot assay is used for confirmation.

- It is important to remember that seroconversion (positive HIV antibody test) may not occur for up to 6 months following exposure and infection.

Several HIV test technologies have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that vary by fluid tested (whole blood, serum, plasma, oral fluids, and urine) and time required to run the test (conventional vs. rapid tests). Testing options facilitate access to testing and increase acceptability of testing.

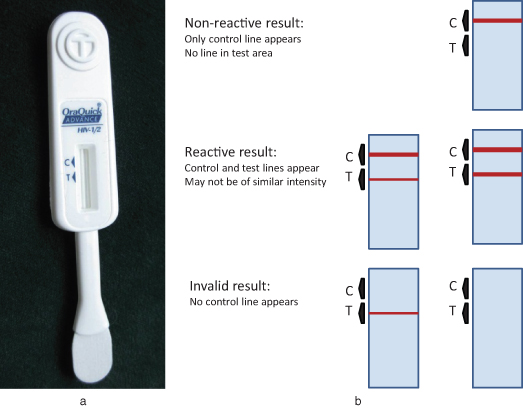

The OraQuick ADVANCE® Rapid HIV-1/2 antibody test (OraSure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA) is a way to measure HIV-antibody response in oral mucosal exudate in 20 minutes and can be used in the dental office. See Fig. 11.1.

Figure 11.1 (a) Test swab; (b) test results. OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 antibody test (OraSure Technologies, Inc.).

CD4+ Lymphocyte Counts

Normal range: 600–1600 cells/µL of blood; median: 1000 cells/µL:

- This is the most widely available marker of immune system competence in the patient with HIV/AIDS.8

- It is an excellent predictor of pending risk of HIV-associated opportunistic infection, disease progression, and survival in clinical trials and cohort studies.

- This guides the prophylactic use of antimicrobial medications to prevent the appearance of HIV opportunistic infections.

- Initial immune suppression (CD4 < 500 cells/µL) signals the first appearance of systemic and oral opportunistic infections.

- Severe immune suppression (CD4 < 200 cells/µL) predisposes patients to life-threatening infections (e.g., toxoplasmosis and cryptococcosis).

- CD4+ counts may be obtained every 6–12 months or more frequently if a patient is altering the ART regimen or has new clinical signs or symptoms.

HIV Viral Load

Dynamic range <40 to >750,000 copies/mL:

- This is the most widely available marker of viral replication in the HIV-positive individual.8

- It is most commonly assessed by a reverse transcriptase-initiated polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique to determine the number of copies of HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) in the peripheral blood.

- It is an excellent predictor of pending risk of CD4+ cell decline over a 3- to 4-month period and thus, HIV-associated opportunistic infections.

- This guides the selection and modification of ART regimens with achieving and maintaining an undetectable viral load (e.g., HIV RNA < 40 copies/µL) as the goal.

- It is obtained at baseline prior to initiating ART, 4 weeks after treatment initiation or regimen change, and reassessed every 3–4 months (or whenever a CD4+ cell count is obtained).

Hematology

In patients who are HIV positive, routine hematological tests are often assessed, which include

- total white blood cell count;

- differential white blood cell count, including absolute neutrophil count (ANC);

- hematocrit and hemoglobin;

- platelet count.

While all values may be suppressed, particularly in advanced AIDS, it is rare that the values are suppressed to critical levels that would require medical management or transfusion prior to dental surgical procedures.9 When this is the case, the patient is likely to report thrombocytopenia or severe neutropenia on the health history.

Medical Treatment

The goals of medical treatment are to decrease the viral load, increase the patient’s immune competence, and treat or prevent opportunistic infections. ART currently includes the following five drug classes:

- nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs);

- non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs);

- protease inhibitors (PIs);

- entry inhibitors (chemokine coreceptor antagonists or fusion inhibitors);

- integrase inhibitors.

Currently, a standard ART regimen does not exist, and therefore, a regimen consists of a combination of drugs from different classes typically referred to as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).10 The parameters used to develop a regimen for individual patients include viral load levels and CD4+ count, and drugs are selected in combination to interfere with multiple stages of HIV replication. In an effort to identify antiretroviral drug-resistant HIV strains and to assist in drug selection, genotyping and phenotyping may be performed.

III. Dental Management

III. Dental Management

Evaluation

The HIV-infected patient should have a comprehensive dental evaluation that includes a complete radiographic examination. Particular attention should be given to detecting the presence of orofacial manifestations associated with HIV infection. The examination should be done with consideration of the patient’s immunological and hematological status and general medical condition.

Key questions to ask the patient

Key questions to ask the patient- What medications are you currently taking?

- When were you last tested for CD4+ count and viral load? Do you know the results?

- When were you last tested for TB and what was the result? If positive, did you take preventive medications and for how long?

- Do you have any drug allergies, for example, itching, swelling, or breathing problems, after taking medicines?

- Have you had or do you have hepatitis B or C or liver cirrhosis?

- Have you had any bleeding problems?

- Has your physician ever told you that you had endocarditis?

- Do you currently smoke, drink alcohol, or use recreational drugs?

- Do you have a prosthetic joint?

- Are there any other medical problems for which you are currently being evaluated or treated, for example, hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease?

Key questions to ask the physician

Key questions to ask the physician- What medications is the patient taking and do you feel the patient is adherent to the recommended drug regimen?

- What is the latest CD4+ count and viral load and have they been stable or rising or declining over time?

- What is the patient’s current TB screening status/result?

- What is the most recent complete blood count (CBC) with differential, platelet count and additional coagulation studies if they have been done?

- Has the patient been assessed for HBV or HCV infection? If so, what was the result?

- Does the patient have a cardiac valvular prosthesis or a history of endocarditis that requires antibiotic prophylaxis?

- Does the patient have a prosthetic joint for which you recommend antibiotic prophylaxis?

- Are there any other medical concerns about the patient that you would like to share?

Dental Treatment Modifications

With these key questions answered and appropriate modifications taken, HIV-infected patients can safely receive dental care. The patient’s “chief complaint” should be addressed promptly with infection eliminated and preventive habits established. Maintaining gingival and periodontal health may help to prevent the rapid forms of periodontal destruction that may occur with immune suppression. Appropriate emergency treatment should be rendered and pain relieved in all stages of the disease.

The majority of HIV-infected patients will be medically healthy, thus requiring little or no modification of dental treatment. With advanced HIV disease, timing or extent of the dental treatment plan may need to be modified according to the immunological and hematological status and general medical condition of the patient. Fatigue during prolonged procedures may be experienced by patients with significant anemia. The frequency of follow-up dental appointments should be arranged on an individualized basis in order to closely monitor oral health.

Coinfections of Concern to Dentistry

TB (See also Chapter 3)

TB is spread by airborne transmission, particularly in closed spaces, of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. People coinfected with HIV and TB have a substantially increased risk of developing active TB compared with the 5% early and 5% late risk for immune-competent persons without HIV infection. Longer courses of therapy and prophylaxis are recommended for HIV-infected patients with TB.

All HIV-infected persons should be given a tuberculin skin test.11 The Mantoux skin test should be repeated annually along with anergy testing, using control allergens such as tetanus or Candida, because anergy is more common in individuals with reduced CD4 counts.

The dental team should be alert to possible signs and symptoms of TB including general symptoms of fatigue, malaise, weight loss, fever, and night sweats as well as pulmonary symptoms of prolonged coughing or coughing up blood. Referral to a physician for evaluation and needed treatment prior to elective dental care is recommended. Patients should not receive elective dental care until they are noninfectious. A definitive noncontagious status can be confirmed by three consecutive negative sputum cultures for acid-fast bacilli. Emergent dental care should be provided in a facility that has the capacity for airborne infection isolation and has a respiratory protection program in place.

Hepatitis B (HBV)/Hepatitis C (HCV) Virus Infection (See also Chapter 6)

Due to similar routes of transmission, there is an increased prevalence of HBV/HCV infection among those with HIV, with HCV found in approximately one-third of all HIV-infected people in the United States.12 HBV or HCV infection may impact the course and management of HIV disease by increasing the risk of ART-induced hepatotoxicity. HIV coinfection is associated with higher HCV viral loads and a more rapid progression of HCV-related liver disease, which leads to an increased risk of cirrhosis.

Viral hepatitis that is sufficiently severe to result in liver dysfunction, will lead to altered drug metabolism and coagulopathies. Patients with significant liver disease may require additional coagulation laboratory tests such as the prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) to assess function of the liver-dependent coagulation Factors II, VII, IX, and X, and liver function tests to gauge the ability of the liver to metabolize drugs.

Oral Lesion Diagnosis and Management

A number of oral lesions have been associated with HIV disease.6,13 Suggested drug treatment regimens for several common or severe oral conditions are presented in Table 11.2. Oral candidiasis is the most frequently occurring oral manifestation of HIV. It indicates an increased risk of HIV disease progression and is associated with reduced CD4+ counts. Oral hairy leukoplakia is considered the second most common oral lesion among HIV-seropositive adults. Prevalence of oral lesions associated with HIV varies across study population, with most HIV-infected adults having oral candidiasis and/or hairy leukoplakia at some point during the course of disease progression. Among HIV-infected children, oral candidiasis, aphthous stomatitis, parotid gland enlargement, and linear gingival erythema may occur. The use of HAART has improved the immune competence of individuals with HIV and thus decreased the prevalence of most oral mucosal diseases.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses