Chapter 11

Gastrointestinal Disease

Gastrointestinal diseases such as peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pseudomembranous colitis are common and may affect the delivery of dental care. When a patient who has one of these conditions presents for treatment, several areas of clinical importance require consideration by the dental practitioner. The dentist must be cognizant of the patient’s condition, must monitor for symptoms indicative of initial disease or relapse, and must be aware of drugs that interact with gastrointestinal medications or that may aggravate these conditions. In addition, oral manifestations of gastrointestinal disease are not uncommon, so the dentist also must be familiar with oral patterns of disease.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Definition

A peptic ulcer is a well-defined break in the gastrointestinal mucosa (greater than 3 mm in diameter, as defined by many industry-sponsored studies) that results from chronic acid or pepsin secretions and the destructive effects of and host response to Helicobacter pylori. Peptic ulcers develop principally in regions of the gastrointestinal tract that are proximal to acid and pepsin secretions (< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

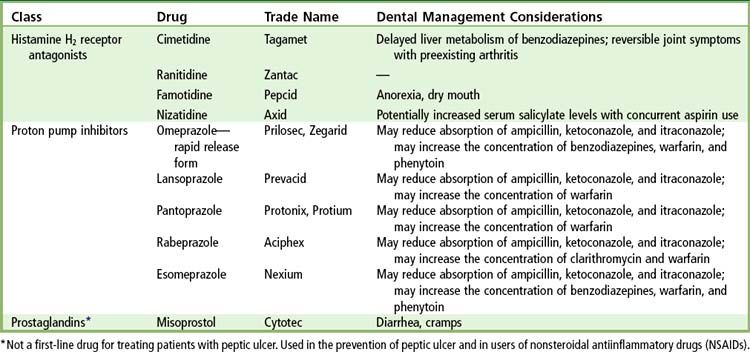

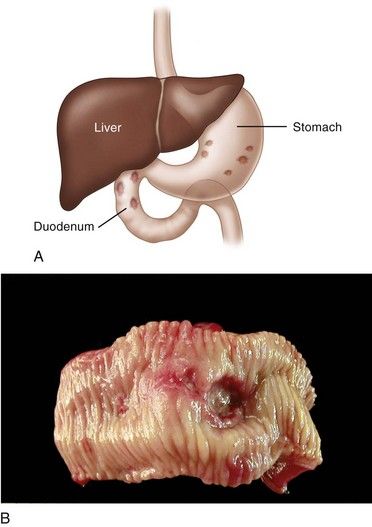

FIGURE 11-1 A, Location of peptic ulceration (shaded areas). Darker-stippled areas are higher-risk sites. B, Peptic ulcer of the duodenum.

(B, From Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N, editors: Robbins & Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders. Courtesy Robin Foss, University of Florida–Gainesville.)

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence

Peptic ulcer disease is one of the most common human ailments, once affecting up to 15% of the population in industrialized countries. Current estimates suggest that 5% to 10% of the world population is affected, and 350,000 new cases are diagnosed annually in the United States.

Peak prevalence of peptic ulceration has shifted to the elderly population.

The disease is rare in children, with only 1 in 2500 pediatric hospital admissions attributable to peptic ulceration.

Etiology

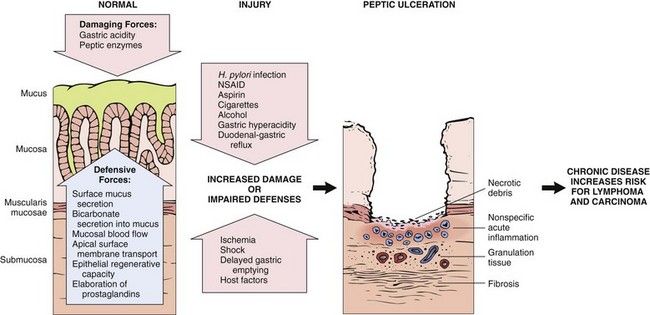

Peptic ulcers result when the balance between aggressive factors that are potentially destructive to the gastrointestinal mucosa and defensive factors that usually are protective of the mucosa is disrupted (

FIGURE 11-2 Complex interplay of aggressive and defensive factors involved in the formation of peptic ulcer disease.

(Modified from Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N, editors: Robbins & Cotran pathologic basis of disease, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

H. pylori is a microaerophilic, gram-negative, spiral-shaped motile bacillus with 4 to 6 flagella.

Humans are the only known hosts of H. pylori. This bacterium infects 0.5% of adults annually—a rate that has been declining since the early 1990’s.

Use of NSAIDs is an etiologic factor in 15% to 20% of cases of peptic ulcer.

Pathophysiology and Complications

Ulcer formation is the result of a complex interplay of aggressive and defensive factors (see

Under normal circumstances, food stimulates gastrin release, gastrin stimulates histamine release by enterochromaffin-like cells in the stomach, and parietal cells secrete hydrogen ions and chloride ions (hydrochloric acid). Vagal nerve stimulation, caffeine, and histamine also are stimulants of parietal cell secretion of hydrochloric acid.

H. pylori is strongly associated with peptic ulcer disease

H. pylori is associated with the development of a low-grade gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.

Peptic ulcers rarely undergo carcinomatous transformation. Ulcers of the greater curvature of the stomach have a greater propensity for malignant degeneration than do those of the duodenum. Evidence that long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) increases the risk for atrophic gastritis and stomach cancer remains controversial; however, the eradication of H. pylori halts progression of atrophic gastritis and may lead to regression of atrophy.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Although many patients with active peptic ulcer report no ulcer symptoms, most experience epigastric pain that is long-standing (several hours) and sharply localized. The pain is described as “burning” or “gnawing” but may be “ill-defined” or “aching.” The discomfort of a duodenal ulcer manifests most commonly on an empty stomach, usually 90 minutes to 3 hours after eating, and frequently awakens the patient in the middle of the night. Ingestion of food, milk, or antacids provides rapid relief in most cases. In contrast, patients with gastric ulcers are unpredictable in their response to food; in fact, eating may precipitate abdominal pain. Symptoms associated with peptic ulceration tend to be episodic and recurrent. Epigastric tenderness often accompanies the condition.

Changes in the character of pain may indicate the development of complications. For example, increased discomfort, loss of antacid relief, or pain radiating to the back may signal deeper penetration or perforation of the ulcer. Protracted vomiting a few hours after a meal is a sign of gastric outlet (pyloric) obstruction. Melena (bloody stools) or black tarry stools indicate blood loss due to gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Laboratory Findings

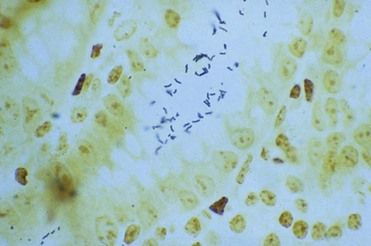

A peptic ulcer is diagnosed primarily by fiberoptic endoscopy and laboratory testing for H. pylori. Endoscopy affords the opportunity for visualization, access for biopsy, and therapeutic procedures if bleeding is present. During endoscopy, a biopsy of the marginal mucosa adjacent to the ulcer is performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancy. A rapid urease test is then performed to detect the bacterial product urease in the mucosal biopsy specimen. Microscopic analysis of biopsied tissue prepared with Giemsa, acridine orange, and Warthin-Starry stains is effective in the microscopic detection of H. pylori (

FIGURE 11-3 Helicobacter pylori organisms (dark rods) evident in the lumen of the intestine. (Warthin-Starry stain.)

(Courtesy Eun Lee, Lexington, Kentucky.)

Nonendoscopic laboratory tests include urea breath tests (UBTs), serologic tests, and, less commonly, H. pylori stool antigen tests. A UBT is a highly sensitive, noninvasive test that involves the ingestion of urea labeled with carbon-13 (

Medical Management

Most patients with peptic ulcer disease suffer for several weeks before going to a doctor for treatment. If the peptic ulcer is confined and uncomplicated and H. pylori is not present, antisecretory drugs are administered (

Four-drug treatment regimens, including a PPI plus three antimicrobials (clarithromycin, metronidazole or tinidazole, and amoxicillin), or a PPI plus a bismuth plus tetracycline and metronidazole, provide the best results for persons with a peptic ulcer and H. pylori infection (

Box 11-1

Antimicrobial Regimens for the Treatment of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Peptic Ulcer Disease

First-Line Therapy

Alternative First-Line Therapy

Data from Rimbara E, Fischbach LA, Graham DY: Optimal therapy for Helicobacter pylori, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8:79-88, 2011.

Prior to 2000, more than 50% of patients with peptic ulcer disease experienced recurrences after treatment. Such recurrence was likely because regimens consisting solely of antisecretory drugs were the treatment of choice; however, these drugs alone do not eradicate H. pylori infection and are noncurative of peptic ulcer disease. Eradication of H. pylori with antibiotic treatment reduces the rate of recurrence of peptic ulceration by 85% to 100%.

In all patients who undergo peptic ulcer therapy, ulcerogenic factors (e.g., use of alcohol, aspirin or other NSAIDs, and corticosteroids; consumption of foods that aggravate symptoms and stimulate gastric acid secretion; persistent stress) should be eliminated to accelerate healing and limit the occurrence of relapse. Patients benefit from smoking cessation, in that perforation rates are higher in smokers, and continued smoking results in a higher relapse rate after treatment and lower rates of eradication of H. pylori.

Elective surgical intervention (e.g., dissection of the vagus nerves from the gastric fundus) largely has been abandoned in the management of peptic ulcer disease. Today, surgery is reserved primarily for complications of peptic ulcer disease such as significant bleeding (when unresponsive to coagulant endoscopic procedures), perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction. On occasions when peptic ulcer disease is associated with hyperparathyroidism and parathyroid adenoma, surgical removal of the affected gland is the treatment of choice. Resolution of gastrointestinal disease occurs after abnormal endocrine function is terminated. Prototype protein-based vaccines against H. pylori continue to be investigated.

Dental Management

Medical Considerations

The dentist must identify intestinal symptoms through a careful history that is taken before dental treatment is initiated, because many gastrointestinal diseases, although they are chronic and recurrent, remain undetected for long periods. This history includes a careful review of medications (e.g., aspirin and other NSAIDs, oral anticoagulants) and level of alcohol consumption that may result in gastrointestinal bleeding. If gastrointestinal symptoms are suggestive of active disease, a medical referral is needed. Once the patient returns from the physician and the condition is under control, the dentist should update current medications in the dental record, including the type and dosage, and should follow physician guidelines. Further, periodic physician visits should be encouraged to afford early diagnosis and cancer screenings for at-risk patients.

Of primary importance are the impact and interactions of certain drugs prescribed to patients with peptic ulcer disease (

Box 11-2 Dental Management

Considerations in Patients with Gastrointestinal (GI) Disease

Patient Evaluation/Risk Assessment (see

Potential Issues/Factors of Concern

| A | |

| Analgesics | Avoid prescribing aspirin, aspirin-containing compounds, and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Use acetaminophen-containing products or celecoxib (Celebrex) in combination with a proton pump inhibitor or misoprostol (Cytotec). |

| Antibiotics | Selection of antibiotics for oral infections may be influenced by recent use of antibiotics for peptic ulcer disease; certain drugs can increase the risk of intestinal flareup in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. Avoid long-term use of antibiotics, especially in elderly and debilitated persons, to minimize risk of pseudomembranous colitis. Monitor for signs or symptoms (diarrhea, GI distress) suggestive of pseudomembranous colitis or disease worsening. Contact patient’s physician if GI symptoms worsen while patient is on antibiotics, so that alternative therapies can be initiated. |

| Anesthesia | No issues. |

| Anxiety | Intraoperative sedation can be provided by an oral, inhalation, or intravenous route. |

| Allergy | No issues. |

| B | |

| Bleeding | Use of acid-blocking drugs and proton pump inhibitors can enhance the blood levels of warfarin (Coumadin). Obtain complete blood count if medication profile increases patient risk for anemia, leu/> |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses