Temporomandibular Joint Disorders

• Internal Derangement of the Temporomandibular Joint

• Arthrocentesis and Arthroscopy

Myofascial Pain Dysfunction

Imaging

The panoramic radiograph in the current patient reveals no odontogenic or osseous pathology.

Assessment

Myofascial pain dysfunction (MPD) syndrome.

The diagnosis of MPD is largely based on the patient history, which is confirmed with a thorough clinical examination. MPD can occur alone (as in the current patient) or in association with internal derangement of the TMJ (see the section Internal Derangement of the Temporomandibular Joint, later in this chapter).

Giannakopoulos, NN, Keller, L, Rammelsberg, P, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain and in controls. J Dent. 2010; 38:369–376.

Graff-Radford, SB. Temporomandibular disorders and headache. Dent Clin North Am. 2007; 51:129–144.

Hersh, E, Balasubramaniam, R, Pinto, A. Pharmacologic management of temporomandibular disorders. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008; 20:197–210.

Klasser, G, Greene, C. Oral appliances in the management of temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009; 107:212–223.

Kurtoglu, C, Gur, OH, Kurkcu, M, et al. Effect of botulinum toxin-A in myofascial pain patients with or without functional disc displacement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 66:1644–1651.

Okeson, JP, Leeuw, RD. Differential diagnosis of Temporomandibular disorders and other orofacial pain disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2011; 55:105–120.

Schmitter, M, Kress, B, Leckel, M, et al. Validity of temporomandibular disorder examination procedures for assessment of temporomandibular joint status. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; 133:796–803.

Scrivani, SJ, Keith, DA, Kaban, LB. Temporomandibular disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2693–2705.

Vedolin, G, Lobato, V, Conti, P, et al. The impact of stress and anxiety on the pressure pain threshold of myofascial pain patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2009; 36:313–321.

Internal Derangement of the Temporomandibular Joint

Examination

General. The patient is a well-developed and well-nourished woman in no apparent distress.

Imaging

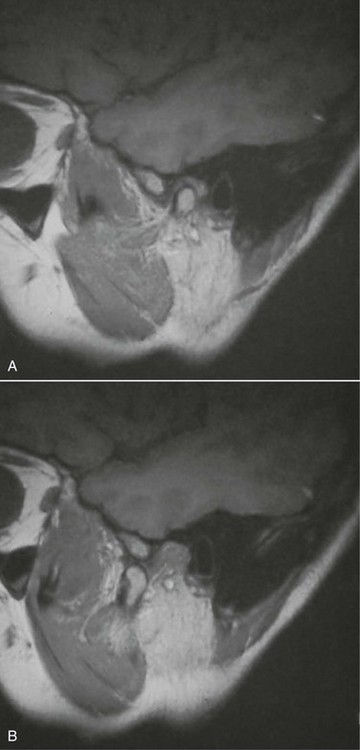

In the current patient, no osseous or dental abnormalities were seen on the panoramic radiograph. Sagittal and coronal MRI scans showed an anteromedially displaced (most frequent location of a dislocated disk) right TMJ disk in the closed mouth position (Figure 10-1, A), which reduced to a normal anatomic relationship in the open mouth position (Figure 10-1, B). The disk demonstrated a normal morphology (anatomy is best seen with T1-weighted images). No joint effusion was seen (inflammation and effusions are best evaluated with T2-weighted images).

Assessment

Patients with ADD with or without reduction may present with or without pain originating from the joint itself or from the muscles of mastication (i.e., myofascial pain dysfunction [MPD]). ADD without reduction presents with different clinical findings, including no opening or closing click, and potentially with restricted condylar translation on the affected side (reduced lateral excursion to the contralateral side). The MRI scan would demonstrate anterior displacement of the disk with no evidence of disk recapture during opening. It is not uncommon for MPD to accompany a painful internal derangement of the TMJ. It is important to distinguish between internal derangement and MPD, because their treatment is very different. MPD may also present as the sole source of pain, which warrants proper diagnosis to avoid unnecessary and inappropriate surgical management (see the section Myofascial Pain Dysfunction earlier in this chapter).

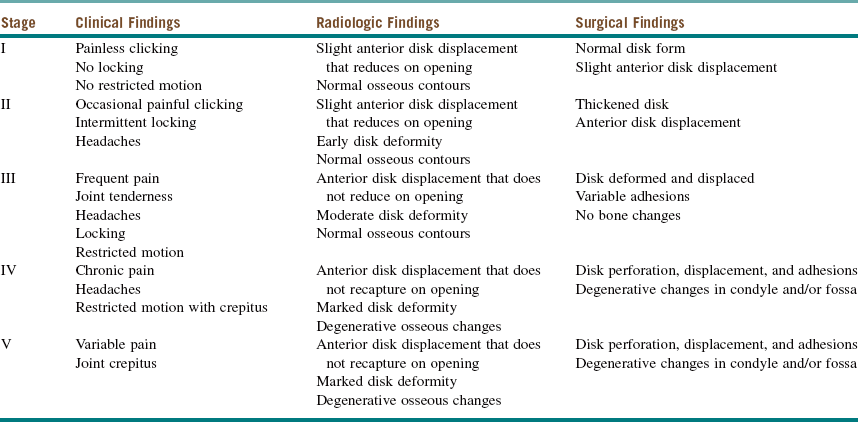

The Wilkes classification system for internal derangement of the TMJ characterizes progression of the disease as having five stages, based on the clinical, radiographic, anatomic, and pathologic features (Table 10-1).

Table 10-1

Wilkes Classification System for Internal Derangement of the TMJ

Modified from Wilkes CH: Internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: pathological variations, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115:469-477, 1989.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses