10

Surgical treatment for sleep-related breathing disorders

CONCEPTUAL OVERVIEW

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2 (ICSD-2) regards sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD) as being “characterized by disordered respiration during sleep.”1 A subcategory of SRBD is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In order to effectively treat OSA, it is imperative to assess which of the upper airway structures are contributory to the diagnosed disorder.

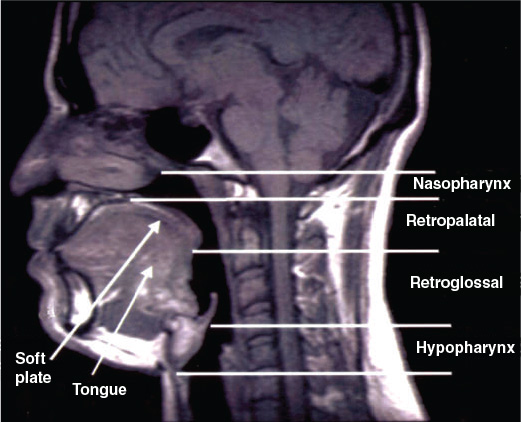

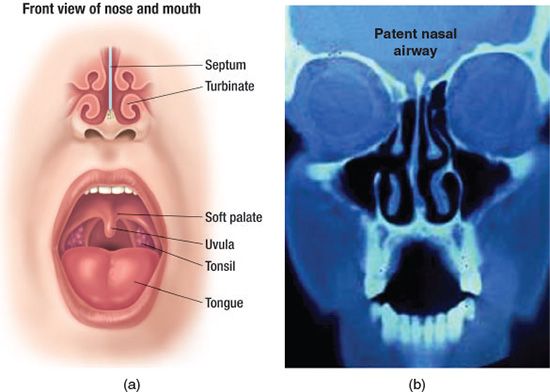

The upper airway can be regarded as being composed of three anatomical zones2 (Figures 10.1 and 10.2):

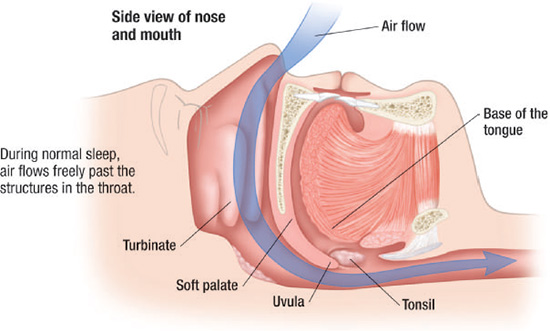

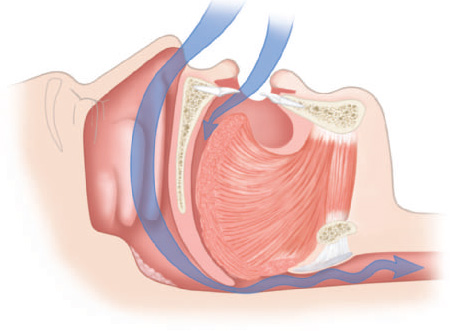

Although obstruction of the upper airway may include multiple anatomical sites, closure of the upper airway is most commonly located in the retropalatal and retroglossal areas (Figures 10.3–10.5).2 Vibration of the airflow past the pharyngeal soft tissues can result in snoring, and a narrowing or collapse of the upper airway may result in obstructive respiratory disturbances during sleep, such as hypopnea or apnea. Surgery of the upper airway may be considered as a management option, especially for patients for whom treatment involving positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy or oral appliance (OA) therapy is not effective or tolerable.

Figure 10.1 Midsagittal MRI of a normal subject. It indicates the regions of the upper airway. (Schwab R. Imaging for the snoring and sleep apnea patient. In: Attanasio R and Bailey D, eds. Sleep Disorders: Dentistry’s Role (Dental Clinics of North America, 45:4). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. 2001; 761. Reprinted with permission.)

Figure 10.2 (a) Normal frontal view of the upper airway. (© Krames Medical Publishing, 2009. Used with permission.) (b) Coronal CT scan of a normal airway with clear paranasal sinuses, relatively straight septum, and normal turbinates, resulting in a patent nasal airway. (Aragon S. Surgical management for snoring and sleep apnea. In: Attanasio R and Bailey D, eds. Sleep Disorders: Dentistry’s Role (Dental Clinics of North America, 45:4). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. 2001; 868. Reprinted with permission.)

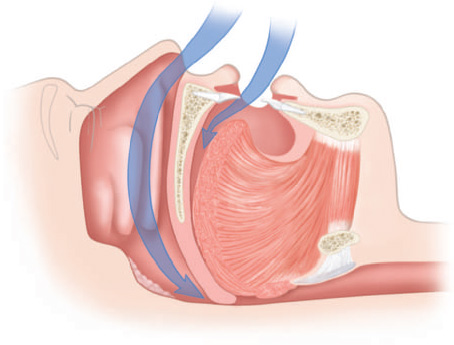

Figure 10.3 Normal sagittal view of the upper airway. (© Krames Medical Publishing, 2009. Used with permission).

The goal of this chapter is to provide an overview of the more common types of surgical intervention techniques that are employed for the management of snoring and OSA.

INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL INTERVENTION

The purpose of surgical intervention is to improve airway patency during sleep by enlarging the upper airway and correction of any disproportionate anatomy.

Figure 10.4 Sagittal view of partially blocked upper airway. (© Krames Medical Publishing, 2009. Used with permission.)

Figure 10.5 Sagittal view of completely blocked upper airway. (© Krames Medical Publishing, 2009. Used with permission.)

Surgery is indicated (1) after unsuccessful nonsurgical conservative therapeutic interventions such as PAP, behavioral approaches (e.g., weight loss, sleep hygiene), and OA; or (2) when an abnormal soft tissue structure is identified as being responsible for the OSA.3

It has been shown that only a very small percentage of patients with OSA have a readily identifiable anatomical area of narrowing or collapse that contributes to the upper airway resistance or collapse.4 Most OSA patients present with a diffuse soft tissue blockage or disproportionate anatomical component of the upper airway that is not always readily observable,4 and thus warrants a complete evaluation.

PRESURGICAL EVALUATION

The purpose of the presurgical evaluation is to identify site-specific areas in the upper airway that contribute to or cause the OSA. These findings become part of the process of determining which surgical approach, if any, is warranted to address the anatomical obstruction.

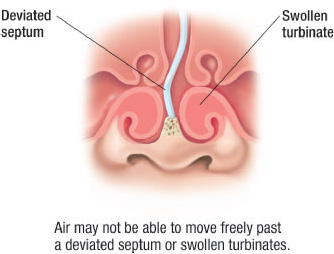

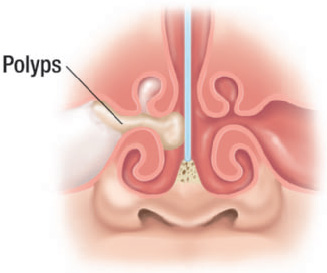

Because different areas of the upper airway may be involved in the etiology of the SRBD, a complete patient evaluation is necessary to (1) assess the probable areas of anatomical involvement in airway narrowing or collapse and (2) determine if any existing pathologies such as neoplasms or cysts are present. Most common clinical findings associated with OSA are disproportionate anatomy such as a large or elongated soft palate (Figure 10.6), a thickened or elongated uvula (Figure 10.7), an enlarged tongue particularly at the base (Figure 10.8), a deviated nasal septum (Figures 10.9 and 10.10), nasal turbinates that are hypertrophic (Figures 10.10 and 10.11), presence of nasal polyps (Figure 10.12), and a hypoplastic or retrognathic mandible.

Figure 10.6 Elongated palatal tissue.

Ideally included in the evaluation is a polysomnogram (PSG) to help determine the extent of the breathing disorder, a comprehensive history, and a comprehensive head and neck clinical examination that includes a nasopharyngolaryngeal examination through the use of a flexible fiberoptic endoscope. The findings from the clinical examination can also be complemented by imaging studies (e.g., cephalometrics, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan).5

The outcomes of an ideal presurgical clinical examination would serve as predictors for the locations of any narrowed or collapsed areas of the upper airway. Unfortunately, because of its subjective nature, clinical examination in and of itself is insufficient for complete assessment of the upper airway in identification of SRBD.6 In addition, clinical examinations, including the use of fiberoptic endoscopy, are generally conducted when the patient is not in a true sleep state.

Figure 10.7 Elongated uvula.

Figure 10.8 Enlarged tongue.

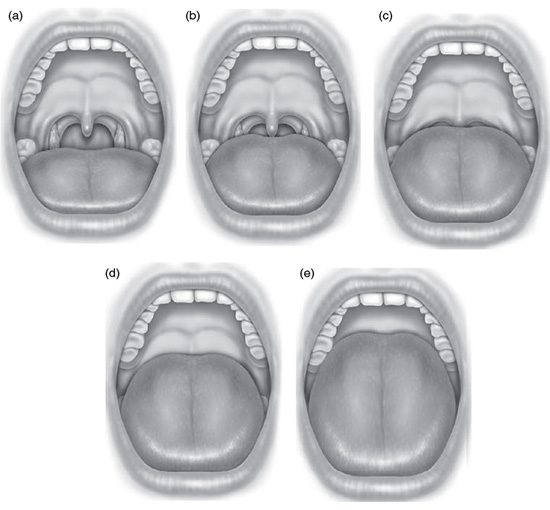

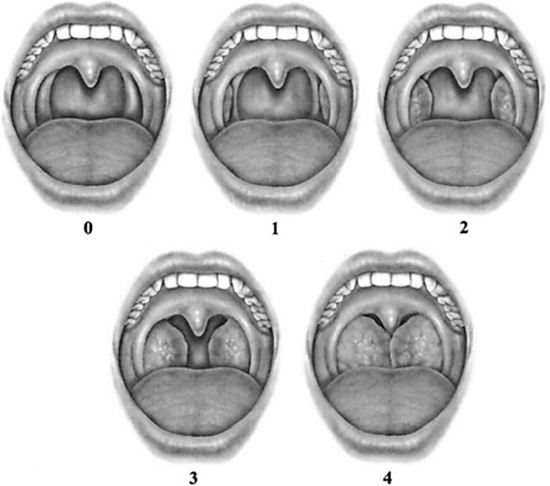

Although the literature does not provide a definitive means of establishing a predictive value regarding which patients would benefit from all surgical techniques,7–9 there have been two classification systems typically used during clinical examinations with respect to pharyngeal anatomy. The first, known as the Mallampati classification, was based on palate position, and it was used as a prognostic indicator relative to the potential difficulties of tracheal intubation.10 Two other clinical staging systems for SRBD were subsequently developed, known as the Friedman classifications, related to tongue position and tonsil size with respect to the palate11,12 (Figures 10.13 and 10.14). The Friedman tongue position classification has been investigated as a prognostic indicator for the presence and severity of obstruction in the hypopharynx region.13

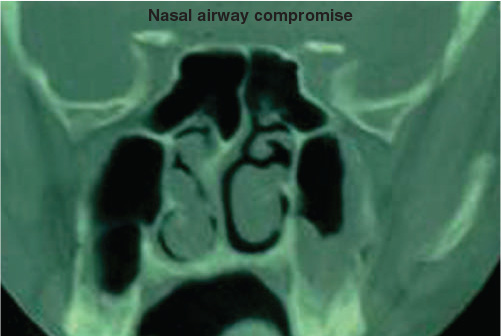

Figure 10.9 Coronal CT scan of an impaired nasal airway because of pansinusitis leading to purulent rhinosinusitis. (Aragon S. Surgical management for snoring and sleep apnea. In: Attanasio R and Bailey D, eds. Sleep Disorders: Dentistry’s Role (Dental Clinics of North America, 45:4). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. 2001; 869. Reprinted with permission.)

Figure 10.10 Frontal view of the upper airway demonstrating a deviated septum and swollen turbinates. (© Krames Medical Publishing, 2009. Used with permission.)

Incorporating a classification with respect to position of the tongue, tonsils, and palate into a complete head and neck examination is warranted for any patient prior to undergoing any surgical intervention for snoring and OSA since the findings may direct the surgeon in the selection and site of surgical treatment.

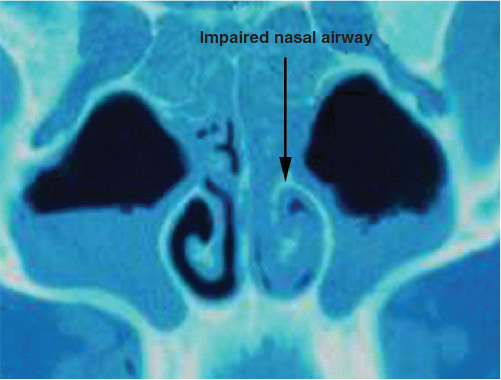

Figure 10.11 Coronal CT scan of a compromised nasal airway because of marked septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, and maxillary sinusitis. (Aragon S. Surgical management for snoring and sleep apnea. In: Attanasio R and Bailey D, eds. Sleep Disorders: Dentistry’s Role (Dental Clinics of North America, 45:4). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. 2001; 869. Reprinted with permission.)

Figure 10.12 Frontal view of the upper airway demonstrating polyps. (© Krames Medical Publishing, 2009. Used with permission.)

TYPES OF SURGERY

On the basis of the outcomes of the presurgical evaluation, surgical treatment is site-specific. There are a variety of surgical procedures available, ranging from minimally invasive to more invasive. The purpose of the minimally invasive procedures is to obtain relatively small changes in the structures and biomechanics of the upper airway, whereas the more invasive procedures are meant to achieve significant removal of tissues and sometimes also a repositioning of anatomical structures (e.g., advancement of the mandible and/or maxilla).

Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy was the first surgical procedure introduced for the treatment of OSA.14 However, since the employment of PAP therapy and other surgical procedures, tracheostomy is no longer the standard surgical treatment for OSA.15 Also, when compared with PAP therapy and the other surgical procedures, tracheostomy is regarded to have adverse psychological, social, and esthetic effects.

This procedure completely bypasses any obstruction in the upper airway because it is performed distal to both the larynx and the pharynx. As such, this procedure has been demonstrated to result in significant improvement of OSA.16

Despite the aforementioned adverse effects, tracheostomy is still indicated when (1) the severe OSA is life-threatening from an immediate obstruction or associated with significant comorbidity, (2) PAP therapy is either not tolerated or it does not address the severe deoxygenation, and (3) airway control is needed during upper airway reconstruction.

Figure 10.13 Friedman tongue position classification. (a) FTP I allows visualization of the entire uvula and tonsils/pillars. (b) FTP IIa allows visualization of most of the uvula, but the tonsils/pillars are absent. (c) FTP IIb allows visualization of the entire soft palate to the base of the uvula. (d) FTP III allows visualization of some of the soft palate, but the distal structures are absent. (e) FTP IV allows visualization of the hard palate only. (Friedman M, Soans R, Gurpinar B, et al. Interexaminer agreement of Friedman tongue positions for staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008; 139:373. Reprinted with permission.)

Nasal surgery

Even though narrowing and collapse of the upper airway occur mostly in the retropalatal and retroglossal areas, the nasal portion of the upper airway can have a significant effect on these sites. One of the functions of the nasal airway is to allow for a level of resistance in the upper airway. If there is an increase in the level of resistance in the nasal airway, there can be a related increase in pharyngeal negative pressure that may contribute to the narrowing and even obstruction of the airway in the velopharyngeal and hypopharyngeal areas.5

Figure 10.14 Tonsil size is graded from 0 to 4. Tonsil size 0 denotes surgically removed tonsils. Size 1 implies tonsils hidden within the pillars. Tonsil size 2 implies the tonsils extending to the pillars. Size 3 tonsils are beyond the pillars but not to the midline. Tonsil size 4 implies tonsils extended to the midline. (Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Lee G, et al. Combined uvulopalatalpharyngoplasty and radiofrequency tongue base reduction for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003; 129(6):614. Reprinted with permission.)

Impaired nasal breathing can result in individuals who are sensitized from exposure to high allergens or in individuals suffering from rhinitis. This experience of impaired nasal breathing during sleep can result in poor sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness. It is not uncommon during sleep for nasal congestion to cause an individual to mouth breathe, and therefore rotating the mandible down and back. When this occurs, the base of the tongue can narrow the airway space in the pharynx. Thus, nasal airflow resistance could have an impact on the severity of SRBD.17,18

Investigations have demonstrated that sleep quality worsened with experimental nasal occlusion.19–21 Individuals are at greater risk for developing SRBD if they have rhinitis and n/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses