Chapter 10 Posterior Direct Composites

Section A Posterior Composites

Relevance of Posterior Composites to Esthetic Dentistry

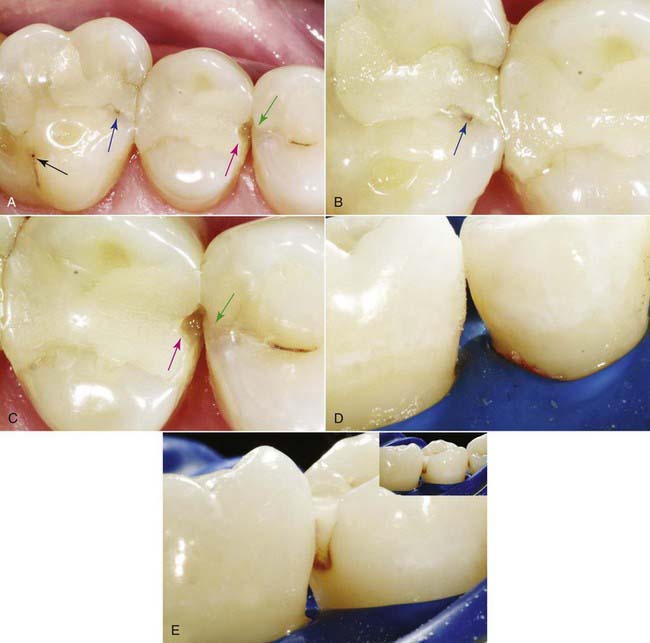

When esthetic dentistry began its evolution, the posterior teeth were considered unimportant. As patient expectations have increased, more focus has been placed on the esthetic contribution of posterior teeth (Figure 10-1). With the mechanics of mandibular function, as humans speak, laugh, and exhibit the behaviors considered human, the incisal edges of the lower anterior teeth and the occlusal surfaces of the posterior teeth are critical (Figure 10-2).

Many patients inhibit behaviors and develop a lack of confidence from a lack of pride in the anterior teeth. The same problems occur with the patient’s quality of life with regard to the posterior dentition. Many practitioners have seen these behaviors in patients with unacceptable anterior teeth. It is a valid exercise to examine the psychology of what happens when posterior tooth esthetics are not ideal. These problems have an impact on both quality of life and self-esteem (Box 10-1). Interestingly, habits such as pursing of lips and raising the hand to cover the mouth are the same regardless of whether patients dislike the appearance of their anterior or their posterior teeth.

Box 10.1 Posterior Dentition’s Impact on Self-Image and Quality of Life

A senior partner at a large, powerful accounting firm commented that she would arrange the seating for business meetings so that her colleagues were seated directly in front of her rather than to the side. Why? So that they would not see her maxillary bicuspid, which had a small interproximal display of gold. The culprit was a gold onlay placed by her previous dentist 20 years earlier. Over time a dinginess often occurs with interproximal metal restorations (see Figure 10-1, A and B).

Happily, this patient chose a comprehensive esthetic reconstruction (see Figure 10-1, C to E). She now smiles and laughs and conducts meetings without rearranging the chairs in the room.

The Five Cs

The C-Factor

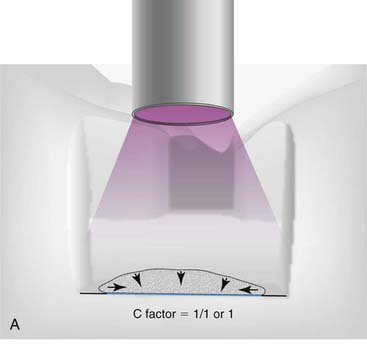

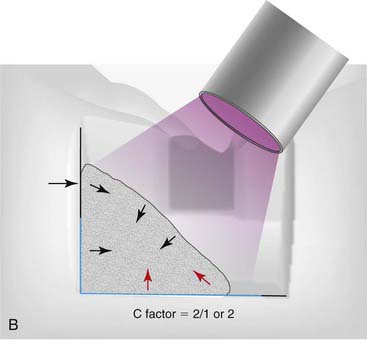

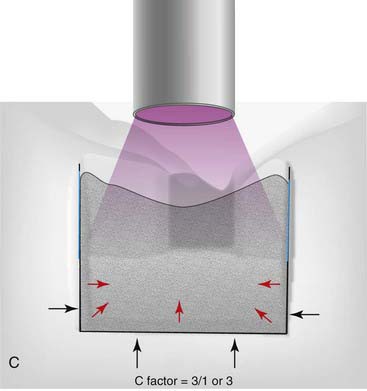

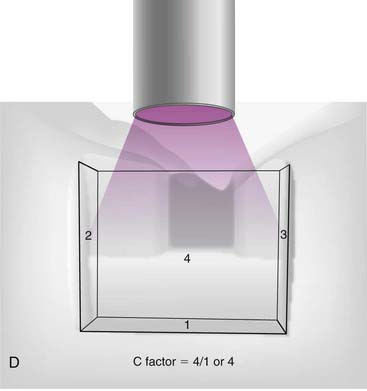

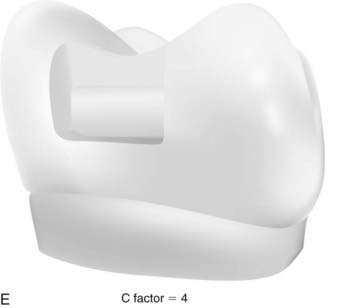

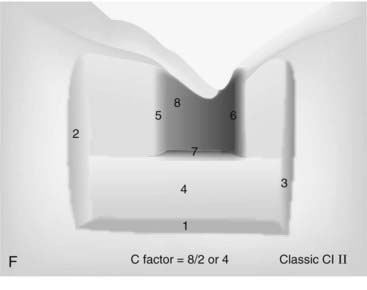

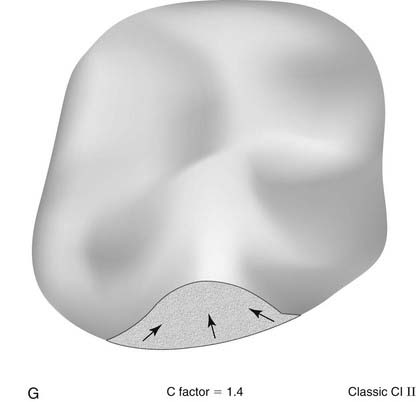

The C-factor is a concept that is bandied about by many in the dental community. Although the concept has never been proven scientifically, it is the best guide to the management of polymerization shrinkage in various cavity preparations. C-factor stands for configuration factor and expresses the ratio of internal walls versus external surfaces. A second way to describe C-factor is internal surface area versus external surface area. C-factor is a fundamental flaw in traditional cavity preparations because the parallel walls for resistance and retention work against the dentist during polymerization shrinkage (Figure 10-3).

As the curing light hits the composite, it will shrink toward the center (Figure 10-4). The shrinkage can be measured as either volume or linearly. On a linear basis, most direct composites shrink 2% to 5%. All composites shrink on polymerization at this point, but the way the composite shrinks is critical and is based on the C-factor. The shape of the cavity preparation, the number of opposing walls, how they oppose one another, and the angle at which they oppose one another are extremely critical to the behavior of composite shrinkage.

The C-factor is a ratio of the internal walls divided by the external walls, or it can be expressed in terms of surface area of the external surface. For C-factor a high number is unfavorable. Realistically a number of 2 or above is a problem when it comes to performance of the composite. Stress that is put onto the tooth and or composite can compromise the bond, cause microfracturing of the enamel, and lead to lack of adhesion in certain areas of the composite. The higher the C-factor, the worse for the situation. To simplify things, basically everything that dental school taught students about making a good preparation for amalgam with retention and resistance form are problematic for composite because of the C-factor (Figure 10-5).

Contamination

Contamination during posterior composite use occurs realistically in three ways:

1. Residual bacteria. Caries present on the tooth must be completely removed, although deep in the tooth some residual caries can be acceptable. The modern method of pulp capping is to avoid pulpal exposure if at all possible. Follow-up of teeth with indirect pulp caps has demonstrated that when small amounts of carious dentin are left over the pulp, after a few months this infected dentin heals and becomes hardened and sterile. However, this should not be misconstrued to assume that sloppy caries removal is acceptable. Within 1.0 to 1.5 mm of the margin, residual contamination in the tooth or as caries often results in recurrent decay.

2. Contamination of the infinity edge margin, or slight extension of the composite past the finish line. The long bevel or infinity edge margin combined with acid etching and bonding the composite a little past the margin is done with great success in anterior sites but has never been fully recognized with posterior placements. For the infinity edge or “Margeas margin,” the composite tends to go slightly past the finish line. Although this can be a strength in anterior restorations and achieves great esthetics, it is more difficult to clean posterior teeth. Compounding the problem is the problem that dentists unfortunately abandon protocols used on anterior teeth when preparing and filling posterior teeth, such as aggressively de-plaquing the teeth with rubber cup and coarse pumice. When the margin is not on enamel but on biofilm, no technique can provide an adequate seal.

3. Contamination that occurs during the restorative process. If fluid—water, saliva, or blood—is incorporated into the composite material, problems result. With amalgam, contamination is less detrimental.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses