Nasal Airway Considerations in the Evaluation and Treatment of Dentofacial Deformities

• Frequent Causes of Chronic Obstructive Nasal Breathing

• The Effects of Respiratory Pattern and Jaw Posture on Maxillofacial Growth

• Simultaneous Management of Chronic Obstructed Nasal Breathing and the Presenting Dentofacial Deformity

• Approaching the Nasal Airway Through Le Fort I Down-Fracture

• Management of Residual Postoperative Nasal Obstruction

• Effects of Maxillary Arch Expansion and Nasal Floor Recontouring on the Airway

• Comprehensive Approach to Chronic Nasal Airway Obstruction

“Irregularities of the teeth being so frequently associated with some pathologic obstruction of the nasal passages or nasopharynx, this fact should ever be present in the operator’s mind and suitable examination being made; and in case [as is often found] the oral deformity be complicated by the presence of hypertrophied faucal tonsils, adenoid hypertrophies in the vault of the pharynx, or obstruction of the nasal passages, the orthodontist’s work can only be made complete by the assistance of a rhinologist and laryngologist.”2

“The nasal fossae are bounded by the maxillary bones and by bones attached to the maxillae; therefore deformities of maxillary bones are bound to influence the size, shape and patency of the nasal fossae. Nasal obstruction may be due directly to deformity or to lack of development of the maxillae. Any [intranasal] bony [obstructions] are removed [surgically] until ample breathing space is established. If nasal obstruction is due simply to lack of size of the nasal fossae and there are erupted [permanent] molar teeth [on each side], then the treatment consists of placing a jackscrew across the mouth from one upper molar to the other. As the screw is spread, the intermaxillary suture opens, the maxillae separate, and the nasal obstruction is relieved.”10

Frequent Causes of Chronic Obstructive Nasal Breathing

Nasal septoplasty is a generic descriptor of the surgical correction of septal thickenings and deflections frequently carried out to improve nasal airflow and sinus drainage (Figs. 10-1 and 10-2).3,7,20,30,52,53,57,75,80,88,89,91,93,94 Enlarged inferior turbinates also commonly obstruct nasal breathing and interfere with sinus drainage (Fig. 10-3). Hypertrophic inferior turbinates that are only minimally responsive to medical treatment are best managed by partial (surgical) reduction.8,23,77 A tight nasal inlet or constricted pyriform apertures occur in conjunction with a narrow maxillary arch (Fig. 10-4).58,86,90,95 An elevated floor of the nose is a frequent finding in the presence of anterior vertical maxillary excess (i.e., long face growth pattern) (Fig. 10-5).63,81,112 A scarred nasal vestibule seen with a repaired cleft nasal malformation may be another cause of persistent nasal obstruction (Fig. 10-6). Nasal septal deformities, inferior turbinate enlargement, a tight nasal inlet, and an elevated nasal floor all commonly coexist with maxillary deformities (Figs. 10-7 and 10-8).1,12–14 Favorable access to the nasal septum, the inferior turbinates, the pyriform apertures, and the nasal floor to correct these airway obstructions and deformities is possible through the Le Fort I down-fracture osteotomy that is commonly used in orthognathic surgery (Figs. 10-9, 10-10, and 10-11).82–85

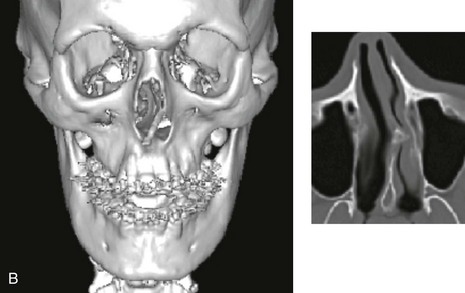

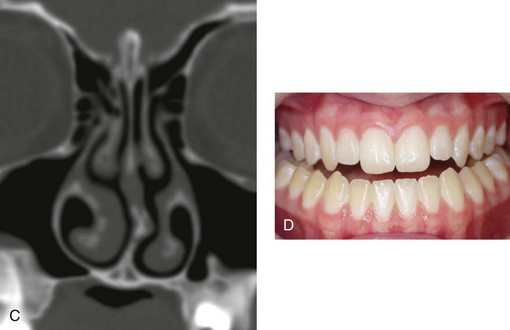

Figure 10-1 A, Three-dimensional maxillofacial and coronal section computed tomography scan views of a child with mandibular deficiency during late mixed dentition. B, Three-dimensional maxillofacial and coronal section computed tomography scan views of a teenager with maxillary deficiency and relative mandibular excess. For both patients, the scans indicate a deviated nasal septum in combination with enlarged inferior turbinates, with an expected increase in nasal airway resistance and diminished breathing space.

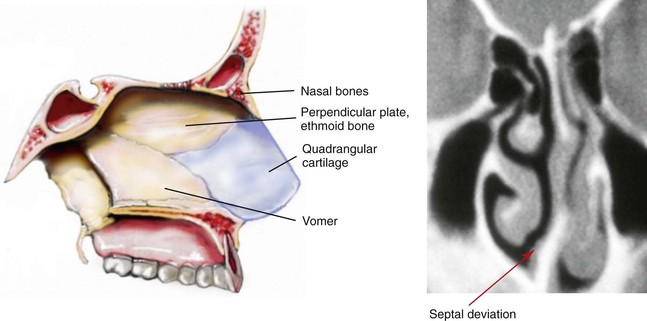

Figure 10-2 Sagittal midfacial illustration and coronal section computed tomography scan view of the skeletal (vomer and perpendicular plate of ethmoid) and cartilage (quadrangular) components of the septum of the nose. The computed tomography scan view indicates deviation and buckling of the septum, which obstructs the left side of the nose. Modified from an original illustration by Bill Winn.

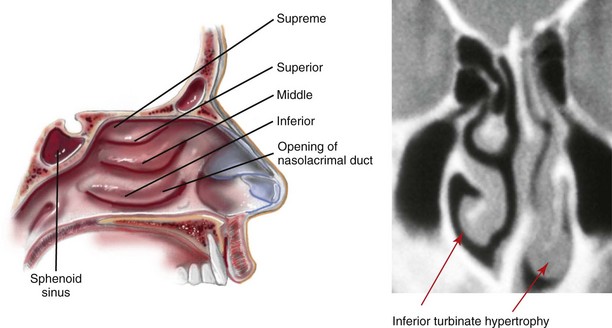

Figure 10-3 Sagittal midfacial illustration and coronal section computed tomography scan showing an axial view of the turbinates. The CT scan view indicates asymmetrical inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Modified from an original illustration by Bill Winn.

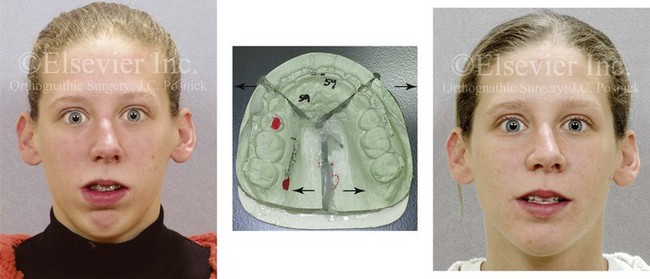

Figure 10-4 A woman in her early 20s shown before and after orthognathic surgery for a long face growth pattern (see Fig. 21-5). Reconstruction also included segmental maxillary osteotomies with arch expansion. This approach also widens the nasal cavity to decrease intranasal airway resistance and improve breathing.

Figure 10-5 A typical teenager with a long face growth pattern demonstrates physical findings that are consistent with a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing (see Fig. 7-2). These findings include septal deviations, inferior turbinate hypertrophy, a narrow (tight) nasal aperture, and an elevated nasal floor.

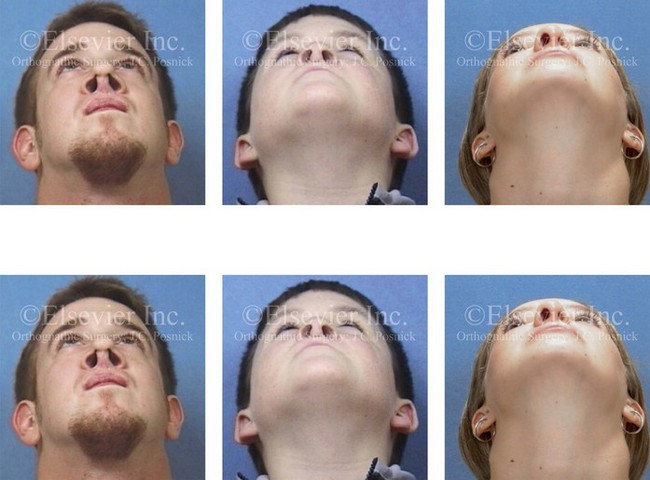

Figure 10-6 Individuals born with cleft lips and palates who have undergone primary repair and secondary reconstruction may present with constrictions of both the internal and external nasal valves. This may be worse as a result of the surgical maneuvers that were previously carried out. Two children with bilateral cleft lip and palate and one with unilateral cleft lip and palate are shown to demonstrate this point. Nasal soft-tissue procedures—including “columella lengthening” in the cases of the bilateral cleft lips and palates and the overzealous resectioning of nasal soft tissues in the case of the unilateral cleft lip and palate—were performed. In all three cases, the nasal valves are constricted (i.e., there is airway obstruction), and the aesthetics are suboptimal.

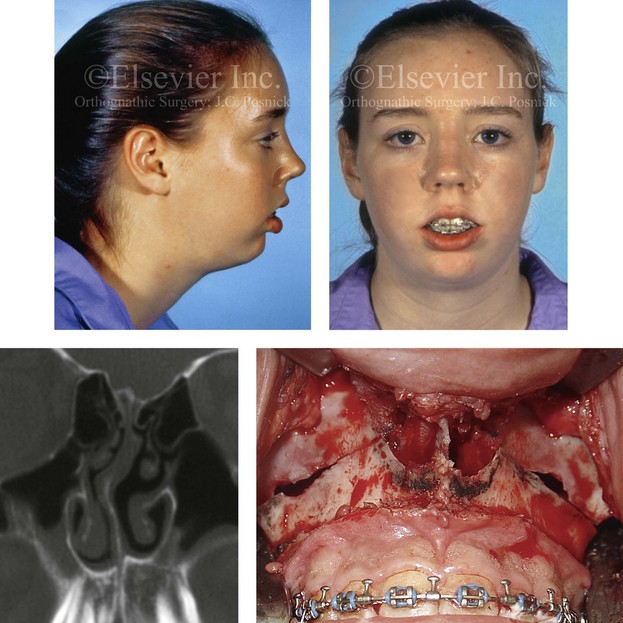

Figure 10-7 A and B, A teenage girl with unilateral cleft lip and palate shows multiple causes of nasal obstruction. These include—as shown in C and D—septal deviations, inferior turbinate hypertrophy, nasal aperture narrowing, and nasal floor deformities, including a residual unrepaired alveolar cleft.

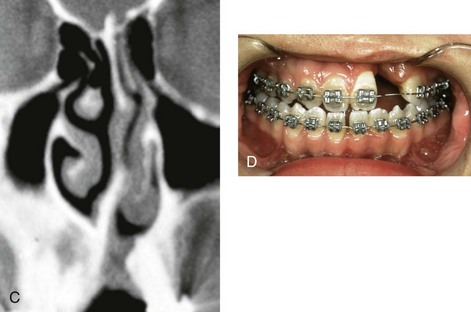

Figure 10-8 A and B, A teenager with a maxillary deficiency and a relative mandibular excess growth pattern. C and D, The physical findings of septal deviations, inferior turbinate hypertrophy, and a narrow (tight) nasal aperture are consistent with the patient’s history of nasal airway obstruction.

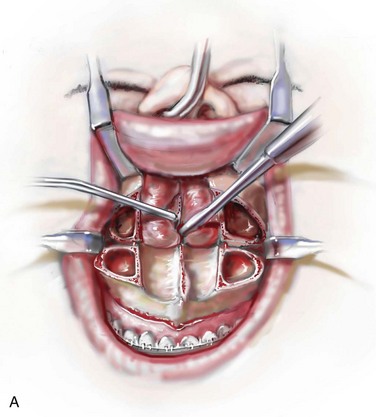

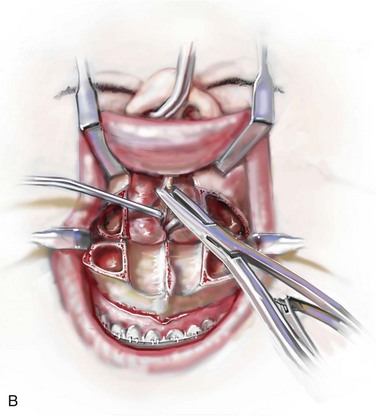

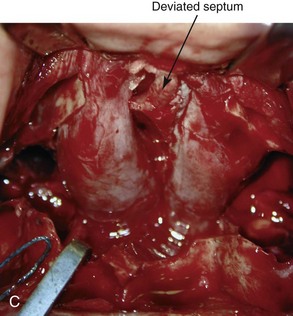

Figure 10-9 Illustrations and intraoperative view of a deformed nasal septum seen through a Le Fort I down-fracture. This is a demonstration of the technique used to carry out the submucous resection of septal bone and cartilage. When indicated on the basis of the patient’s history and clinical examination, attention is turned to the removal of the deviated portions of the septum of the nose. A, With an elevator, the submucosal dissection of the cartilaginous (quadrangular cartilage) and bony (vomer and perpendicular plate of ethmoid) septum is carried out. B, The deviated and thickened aspects of the cartilaginous and bony septum are resected with a rongeur. The more anterior components of the cartilaginous septum that provide needed support to the nasal dorsum and tip are not disturbed. This includes at least 1 cm of the dorsal and caudal cartilage. C, An intraoperative view through a Le Fort down-fracture shows a deviated septum.

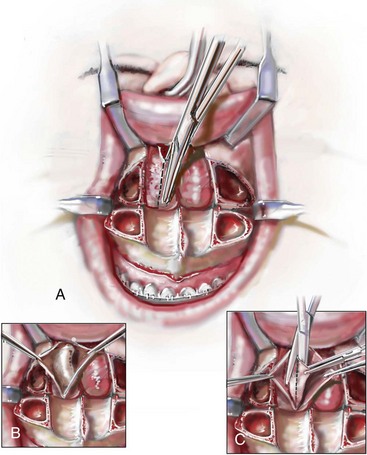

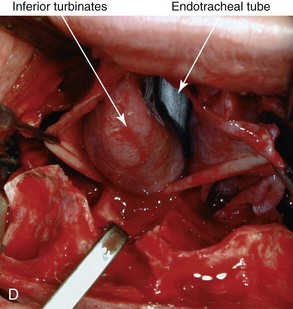

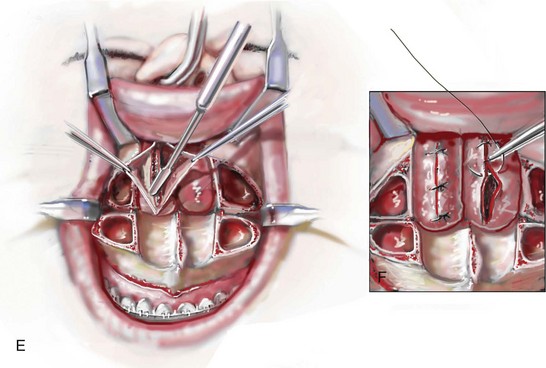

Figure 10-10 Illustrations and intraoperative view of inferior turbinates seen through a Le Fort I down-fracture. This is a demonstration of the technique used to carry out a partial turbinate reduction. A, An incision parallel and just below each inferior turbinates is completed through the nasal mucosa. B, The elevated nasal mucosa flaps expose the enlarged inferior turbinate. C, The resection of the inferior aspect of the hypertrophic inferior turbinate is completed with the use of a straight (Mayo) scissors. D, An intraoperative view of the elevated nasal flaps. The endotracheal tube is also visualized. E, After the partial resection of each inferior turbinate, the raw surfaces are cauterized. F, The nasal mucosa flaps are then closed with interrupted resorbable sutures.

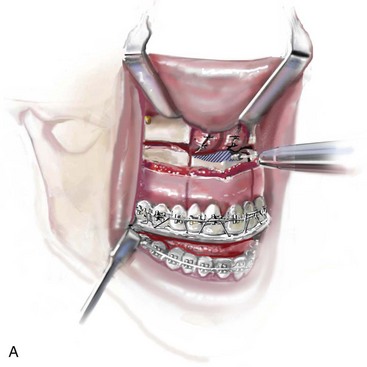

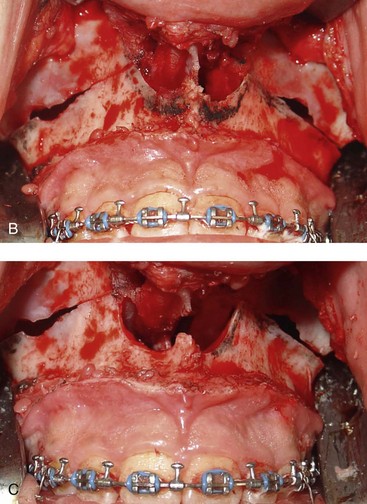

Figure 10-11 Illustration and intraoperative views of the nasal rims and floor seen through a Le Fort I down-fracture to demonstrate the techniques of rim, nasal floor, and anterior nasal spine recontouring with the use of a bur on a rotary drill. A, Illustration of recontouring with rotary drill. B and C, Intraoperative views before and after recontouring, respectively.

Maxillofacial literature has traditionally addressed aspects of nasal obstruction, nasal anatomy, and sinus drainage in the patient who is undergoing orthognathic surgery, but often only in subjective and limited ways.8,18,24,27,32,33,36,38,55,56,71,73,74,76,103,104,107 Authors traditionally discuss the effects of Le Fort I osteotomies on nasal morphology (i.e., aesthetics) and occasionally recommend adjunctive soft-tissue techniques in the hopes of limiting suboptimal aesthetics (e.g., the alar cinch stitch).37 Little consideration is given to either baseline upper airway findings or how the maxillary surgery may affect long-term nasal breathing. Warren and colleagues discusses issues of nasal airway changes after Le Fort I osteotomy with maxillary impaction, advancement, and transverse widening.108 They used a pressure flow meter to assess nasal airway breathing before and after maxillary osteotomies.21,29 Turvey and colleagues recognized preexisting nasal obstruction in many of their orthognathic patients.103 They suggested methods of avoiding adverse effects on nasal airway resistance that may result from Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy procedures.104 Moses and coworkers reported about a series of patients who were treated for nasal obstruction and sinus drainage difficulties after Le Fort I maxillary procedures were carried out for long face growth patterns (e.g., vertical maxillary excess with anterior open bite).71 They concluded that Le Fort I impaction frequently aggravates preexisting nasal airway obstruction and sinus disease. Williams and colleagues examined the nasal airway function (breathing) in a consecutive series of subjects (n = 50) before and 5 months after undergoing (1) Le Fort I osteotomy with advancement and vertical lengthening (2) maxillary segmentation with transverse expansion (14 of 50 subjects, 28%); and (3) recontouring of the nasal floor and pyriform rims with a rotary drill. Despite these favorable nasal airway surgical maneuvers, when ignoring potential pathology of the septum (e.g., buckling and deviation) and the inferior turbinates (e.g., hypertrophy/enlargement), a full 20% of their study subjects experienced a worsening of their nasal airway function after surgery.113a

Unfortunately, in the individual with a dentofacial deformity, a methodic approach to the evaluation and management of chronic nasal airway obstruction at the time of orthognathic surgery is often not undertaken. We suggest that any upper airway obstructions be assessed by the orthognathic surgeon with the same vigor as the effects of the presenting jaw deformities on malocclusion are evaluated (Figs. 10-12 and 10-13).51,83–85,87

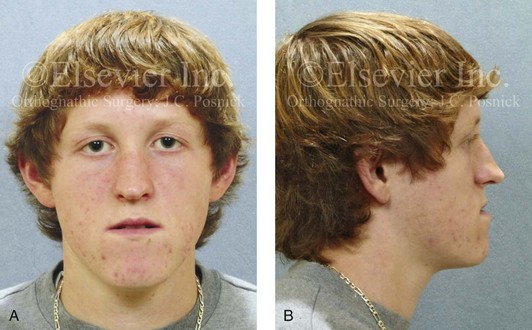

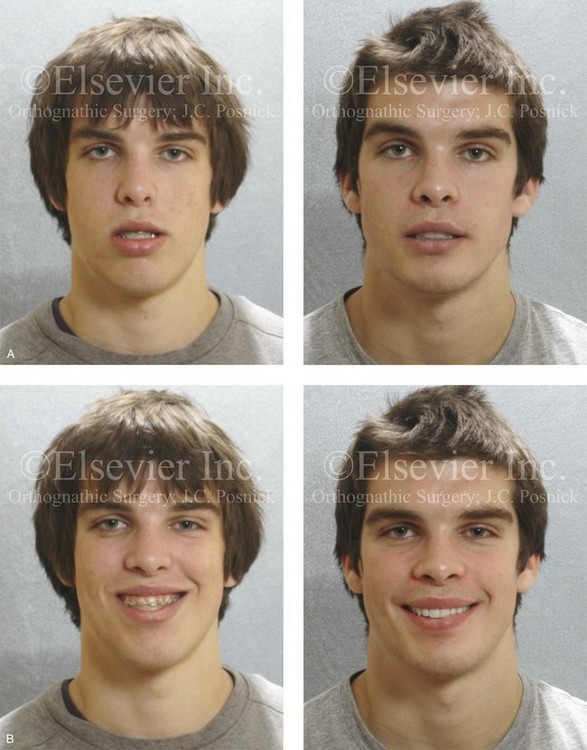

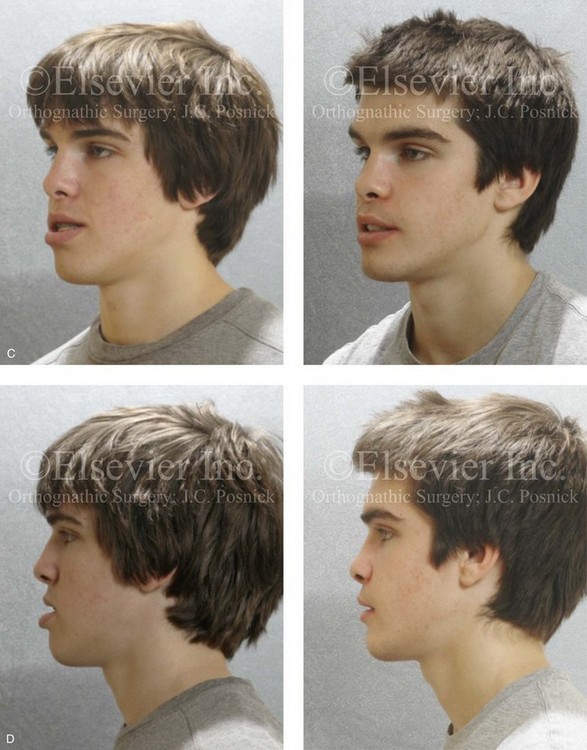

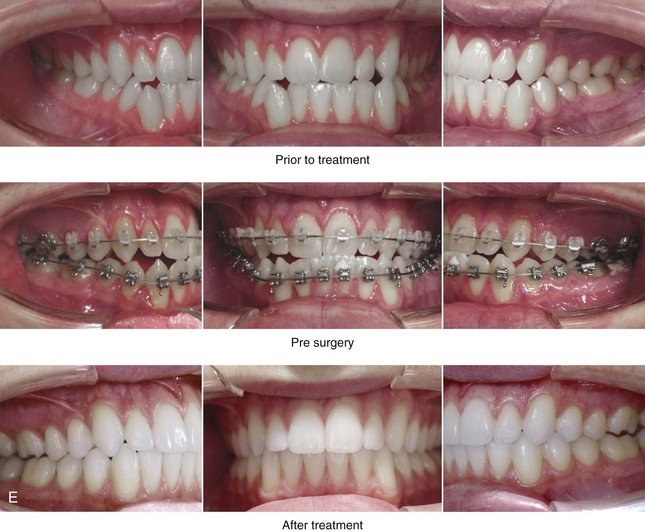

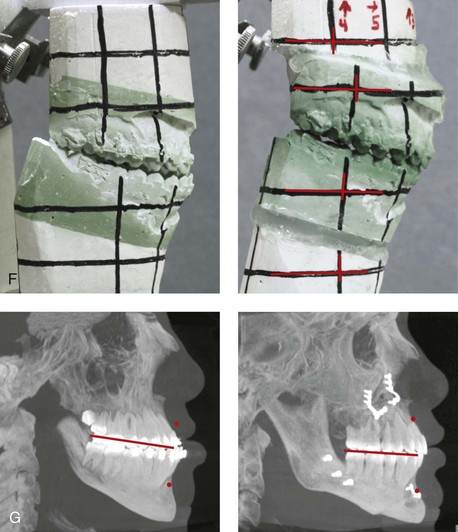

Figure 10-12 A 20-year-old man with a combined long face growth pattern (environmental) and a right side hemimandibular elongation (hereditary). There is an asymmetrical Class III negative overjet malocclusion. The patient had a lifelong history of obstructed nasal breathing with documented septal deviation, hypertrophic inferior turbinates, and an elevated nasal floor. He was referred to this surgeon for evaluation, and he agreed to a comprehensive orthodontic and orthognathic approach. With the relief of dental compensation, the patient’s surgery included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement and vertical shortening); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (mandibular straightening and asymmetrical correction); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, after orthodontic decompensation, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after reconstruction.

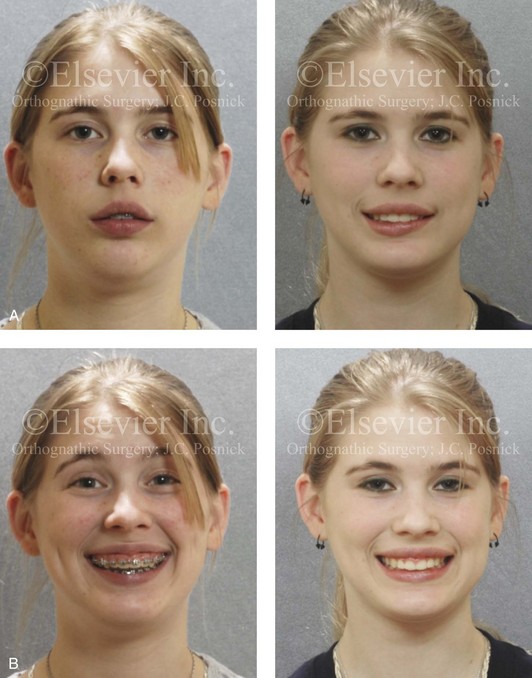

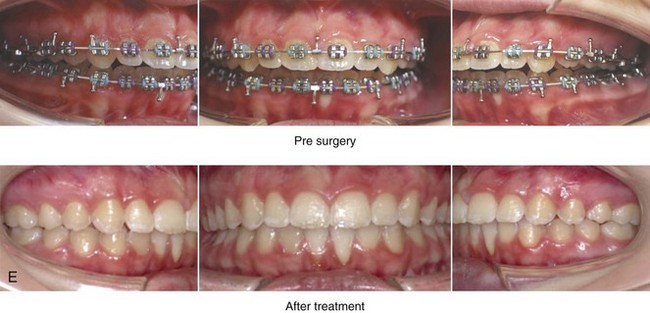

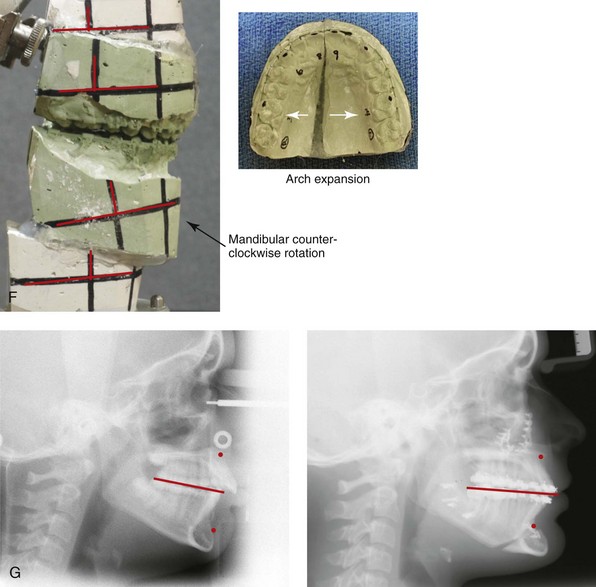

Figure 10-13 A teenage girl with a long face growth pattern is treated with a comprehensive orthodontic and surgical approach. After orthodontic (dental) decompensation, her surgical procedures included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (vertical intrusion, horizontal advancement, and arch expansion) bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); oblique osteotomy of the chin (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and recontouring of the nasal floor. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views with orthodontics in progress and then after surgery. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric views before and after treatment.

The Effects of Respiratory Pattern and Jaw Posture on Maxillofacial Growth

The link between an open mouth or oral breathing pattern and maxillofacial growth has been documented in the literature.4,5,11,17,24,25,28,31,41,

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses