Medical Emergencies

Prevention of Medical Emergencies

Patient Monitoring

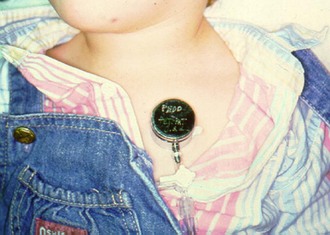

When moderate sedation is used, and especially in children in whom a much narrower margin of safety often exists because of smaller degrees of respiratory and cardiovascular reserve, additional monitoring should be routinely employed. This will include continual monitoring of blood pressure, usually via an automated blood pressure cuff, continuous monitoring of oxygenation and pulse rate via pulse oximetry, and continuous monitoring of ventilation, either with a pretracheal/precordial stethoscope (Figure 10-1; see also Figure 8-5) or a capnograph. These measures are particularly important for patients with whom continual verbal contact is difficult or undesirable. (See Chapter 8 for a detailed discussion of monitoring during sedation.) Presedation and discharge vital signs, including pulse rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure should always be obtained unless prevented by the lack of patient cooperation.

FIGURE 10-1 Use of a precordial stethoscope.

FIGURE 10-1 Use of a precordial stethoscope.

Emergency Equipment

Realizing that basic life support until EMS transport arrives is the foundation of medical management in most situations, it should be apparent that very little equipment is necessary to deal with medical emergencies. When discussing the presence of any emergency equipment where pediatric patients are to be treated, it should be appreciated that appropriate sized equipment will be necessary, potentially for infant to adolescent sized patients; it is the dentist’s responsibility to ensure that the correctly sized equipment is available. Oxygen is the primary emergency drug in the dental office, which requires specialized equipment for its administration. An oxygen source capable of delivering greater than 90% oxygen at flows of 10 L/min for a minimum of 1 hour is ideal. This means that an “E” cylinder is the minimum size required. Since pediatric dental patients only very rarely suffer myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest as the initiating medical event, and because drug-induced respiratory depression and loss of a patent airway during unconsciousness is much more likely to occur, the initial primary goal of basic life support is establishment and maintenance of proper respiratory function. Hypoxemia (low oxygen content in the arterial blood) is the final common pathway leading to morbidity and mortality in the majority of severe pediatric medical emergency situations. Adequate oxygenation is more easily ensured by the administration of supplemental oxygen. If the patient is adequately breathing spontaneously, oxygen may be delivered by way of a facemask, nasal mask, or nasal cannula prongs. Ideally, a non-rebreather facemask should be available as this delivers the highest concentration of oxygen to the spontaneously breathing patient for the most serious medical emergencies. However, should the patient cease breathing during an emergency situation, positive pressure ventilation will be necessary. Although mouth-to-mouth ventilation, or preferably mouth-to-mask ventilation, is possible, this delivers only about 16% oxygen from the rescuer’s lungs and is not ideal, but certainly better than no ventilation in a patient who is not breathing. Therefore a positive-pressure oxygen delivery system (bag-valve-mask device) that can be connected to a high-flow oxygen source is also considered essential equipment to deliver oxygen to the apneic patient (Figure 10-2). As an alternative for those trained in its use, a Robertshaw demand valve device or similar oxygen-powered positive pressure breathing apparatus can also be considered. The bag-valve-mask device, face masks, and oxygen cylinder should all be together in one central location in the office.

FIGURE 10-2 Bag-valve-mask apparatus to deliver positive pressure ventilation to a nonbreathing patient.

FIGURE 10-2 Bag-valve-mask apparatus to deliver positive pressure ventilation to a nonbreathing patient.

A high-volume suction device is another piece of equipment that is considered essential for the management of medical emergencies. Emergency situations, especially those involving an obtunded patient, often induce vomiting. The aspiration of vomitus can be disastrous. This can usually be minimized or prevented by proper patient positioning and suctioning. Of course, most dental offices contain high-volume suction equipment for restorative dentistry purposes. A Yankauer type of suction configured to be connected to the dental high-volume evacuation dental suction unit would be ideal to suction the mouth and pharynx (Figure 10-3).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline

FIGURE 10-3

FIGURE 10-3