10

Autoimmune and Connective Tissue Diseases

I. Background

Conditions commonly referred to as connective tissue diseases and/or autoimmune diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), fibromyalgia (FM), the various sclerosing syndromes such as progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) or scleroderma, and Sjögren’s syndrome (SS). Collectively, these disorders affect a significant portion of the United States population, where patients can often appear to be in good health, but whose medical illness may adversely affect their oral cavity or the provision of dental care.

Description of Disease/Condition

SLE

SLE is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disorder of unknown etiology that affects many organ systems. Autoantibodies and immune complexes set off an array of immunological reactions, resulting in activation of the complement system, leading to vasculitis, fibrosis, and tissue necrosis. The clinical course of SLE is defined by periods of remission and exacerbation.

RA

RA is an autoimmune disease manifesting as a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder. The disease has a wide clinical spectrum with considerable variability in joint and extra-articular manifestations.

PBC

PBC is a chronic and progressive cholestasic disease of the liver. The major pathology of this disease is a destruction of the small-to-medium bile ducts, which leads to progressive cholestasis, liver dysfunction, and ultimately end-stage liver disease.

FM

FM is a syndrome of persistent widespread pain, stiffness, fatigue, disrupted sleep, and cognitive difficulties, often accompanied by multiple other unexplained symptoms, anxiety and/or depression, and functional impairment of activities of daily living.

PSS (Scleroderma)

PSS, or scleroderma, is a disease characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by various degrees of tissue fibrosis and chronic inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs, prominent fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and humoral and cellular immune alterations.

SS

SS is a chronic, autoimmune, inflammatory disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands in multiple sites, most commonly the lacrimal and salivary glands. It can occur alone (primary SS) or in conjunction with another autoimmune rheumatic disease (secondary SS).

Pathogenesis/Etiology

SLE

SLE is the prototype systemic autoimmune disease, as virtually all components of the immune system contribute to the characteristic autoimmunity and tissue pathology. The etiopathogenesis of lupus comprises genetic contributions, environmental triggers, and stochastic events.1 Autoantibodies and their antigens, cytokines, and chemokines amplify immune system activation and generate tissue damage. Autoantibody production occurs years prior to the development of clinical signs and symptoms of SLE.2

RA

Although the cause of RA is unknown, genetic, environmental, hormonal, immunological, and infectious factors may play significant roles.3 An external trigger (e.g., infection, trauma) elicits an autoimmune reaction, leading to synovial hypertrophy and chronic joint inflammation along with the potential for extra-articular manifestations in genetically susceptible individuals. Synovial cell hyperplasia and endothelial cell activation are early events in the pathological process that progresses to uncontrolled inflammation and consequent cartilage and bone destruction.

PBC

PBC is characterized by a T-lymphocyte-mediated assault on small intralobular bile ducts. A constant attack on the bile duct epithelial cells leads to their gradual destruction and eventual disappearance. The sustained loss of intralobular bile ducts causes the signs and symptoms of cholestasis, and eventually results in cirrhosis and liver failure.4

FM

FM is currently understood to be a disorder of central pain processing or a syndrome of central sensitivity. Although the pathogenesis of FM is not completely understood, research shows biochemical, metabolic, and immunoregulatory abnormalities.5

PSS (Scleroderma)

The exact etiology of PSS is unclear; however, the following pathogenic mechanisms are always present: endothelial cell injury, fibroblast activation, and cellular and humoral immunological derangement. Vascular dysfunction is one of the earliest alterations of systemic sclerosis and may represent the initiating event in its pathogenesis.6

SS

The etiology of SS is not well understood. The presence of activated salivary gland epithelial cells expressing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and the identification of inherited susceptibility markers suggest that environmental or endogenous antigens trigger a self-perpetuating inflammatory response in susceptible individuals. In addition, the continuing presence of active interferon pathways in SS suggests ongoing activation of the innate immune system.7

Epidemiology

SLE

- An estimated 161,000–322,000 women are currently afflicted with SLE in the United States, with 1 in 1000 white and 1 in 250 black women affected.8

- Ninety percent are young to middle-aged women.

- The 10-year survival rate is >90%, with 20-year survival rates near 80%.

RA

- An estimated 1.3 million adults have RA.8

- Annual worldwide incidence of RA is approximately three cases per 10,000 population, and the prevalence rate is approximately 1%, increasing with age and peaking at age 35–50 years.

- RA affects all populations, although the disease is much more prevalent in some groups (e.g., 5–6% in some Native American groups) and much less prevalent in others (e.g., black persons from the Caribbean region).

- Women are affected by RA approximately three times more often than men, but sex differences diminish in older age groups suggesting a hormonal component.

PBC

- The incidence of PBC has been estimated as 4.5 cases for women and 0.7 cases for men (2.7 cases overall) per 100,000 population.4

- Women account for 75–90% of patients.

- Men develop similar symptoms and clinical course of disease, but they appear to be at higher risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Onset of PBC usually occurs in persons aged 30–65 years.

FM

- It is estimated that 5 million U.S. adults are afflicted with FM.9

- FM exhibits no race predilection but shows a drastic female predominance with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 9 : 1.

- FM can occur in individuals of all ages.

PSS (Scleroderma)

- An estimated 49,000 U.S. adults have PSS.8

- Incidence and prevalence of PSS are estimated at 19 and 240 cases per million population, respectively.

- Peak onset occurs in individuals aged 30–50 years.

- The risk of systemic sclerosis is four to nine times higher in women than in men.

SS

- Primary SS affects 0.4–3.1 million U.S. adults.8

- SS affects 0.1–4% of the population.

- The female-to-male ratio of SS is 9 : 1.

- SS can affect individuals of any age but is most common in elderly people.

- Onset typically occurs in the 4th–5th decade of life.

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

Coordination of Care between Dentist and Physician

Rheumatological diseases are chronic and often difficult to diagnose. A careful examination of the face, temporomandibular joints, and oral cavity for evidence of oral mucosal dryness or lupus-like oral lesions can assist in the diagnostic process for many of these diseases. Salivary measurements and minor salivary gland biopsies from the labial mucosa can contribute to the diagnosis of SS. The relationship between SS and lymphoma underscores the importance of the oral health-care provider aiding in the diagnosis and monitoring of these patients. Among patients with SS, the incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is 4.3% (18.9 times higher than in the general population), with a median age at diagnosis of 58 years. The mean time to the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after the onset of SS is 7.5 years. In addition, patients with major joint dysfunction who undergo total joint replacement will require consideration for antibiotic prophylaxis (AP). While this is controversial, a decision whether to use prophylactic antibiotics should be coordinated between dentist and physician/orthopedic surgeon on an individualized basis.

II. Medical Management

II. Medical Management

Identification

SLE

The manifestations of SLE exhibit no typical pattern of presentation. Small-vessel vasculitis, resulting from immune-complex deposition leads to renal, cardiac, hematological, mucocutaneous, and central nervous system (CNS) destruction. In addition, polyserositis (inflammation of the serous membranes) results in joint, peritoneal, and pleuropericardial symptoms. Diagnosis is made by a combination of laboratory tests and clinical manifestations including 4 of 11 criteria.10,11

Raynaud’s phenomenon can occur in a variety of rheumatological diseases as shown in Fig. 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Patient’s hand with Raynaud’s syndrome. Note purple tone to fingertips of cyanotic phase.

RA

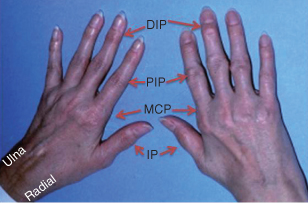

The hallmark feature of this condition is persistent symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that affects the hands (see Fig. 10.2) and feet, although any joint lined by a synovial membrane may be involved. The criterion for an RA diagnosis uses a score-based algorithm based on four areas: joint involvement, serology test results, acute-phase reactant test results, and patient self-reporting of signs/symptom duration. A score of 6 of 10 or greater must be met for a classification of definitive RA applied to patients with synovitis in at least one joint that cannot be better explained by an alternative diagnosis.12 Patients with a score that falls below 6/10 may be reassessed over time. Progression of RA is shown in Table 10.1.

Figure 10.2 Hands of a 43-year-old with rheumatoid arthritis showing small joint synovitis. DIP, distal interphalangeal joint; PIP, proximal interphalangeal joint; MCP, metacarpophalangeal joint; IP, interphalangeal joint.

Table 10.1. Progression of Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Stage 1 (early) | No destructive changes observed upon radiographic examination; radiographic evidence of osteoporosis is possible |

| Stage 2 (moderate) | Radiographic evidence of periarticular osteoporosis, with or without slight subchondral bone destruction; slight cartilage destruction is possible; joint mobility is possibly limited, but no joint deformities are observed; adjacent muscle atrophy is present; extra-articular soft-tissue lesions (e.g., nodules, tenosynovitis) are possible |

| Stage 3 (severe) | Radiographic evidence of cartilage and bone destruction in addition to periarticular osteoporosis; joint deformity (e.g., subluxation, ulnar deviation, hyperextension) without fibrous or bony ankylosis; muscle atrophy is extensive; extra-articular soft-tissue lesions (e.g., nodules, tenosynovitis) are possible |

| Stage 4 (terminal) | Presence of fibrous or bony ankylosis, along with criteria of stage 3 |

PBC

Many people with PBC have no symptoms of the disease when they are initially diagnosed. Routine blood tests for an evaluation for other conditions lead to diagnosis in 25% of patients.

FM

Patients with FM may meet criteria for three or more central sensitivity syndromes. Most patients do not appear chronically ill, although they may look fatigued or agitated.

PSS (Scleroderma)

Some types of scleroderma affect only the skin, while others affect the whole body.

- Localized scleroderma usually affects only the skin on the hands and face. It develops slowly, and rarely, if ever, spreads throughout the body or causes serious complications.

- Systemic scleroderma may affect large areas of skin and organs such as the heart, lungs, or kidneys. There are two main types of systemic scleroderma: (1) limited disease or CREST syndrome = calcinosis, Raynaud’s syndrome, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly (see Fig. 10.3), telangiectasia; or (2) diffuse disease.

Figure 10.3 Sclerodactyly in a patient with scleroderma.

SS

The clinical presentation of SS may vary. The onset is insidious. It usually starts in women aged 40–60 years, but it also can affect men and children. The first symptoms in primary SS can be easily overlooked or misinterpreted, and diagnosis can be delayed for as long as several years.

Medical History and Physical Exam

SLE

Medical history and physical assessment reveals the diversity of this multisystem disease that can have phases of stability and exacerbations, called lupus flares.

- Renal Disease: Localization of immune complexes in the kidney is the precipitating factor in the development of lupus nephritis and can lead to a rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis or a less aggressive form of renal disease resulting from cumulative, chronic tissue injury during previous flares of SLE. Ultimately, cell proliferation, inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis result in significant impairment of renal function.

- Cardiac Disease: Cardiac manifestations include pericarditis, pericardial effusion, myocardial infarction, and valvular disease. The most common of all cardiac lesions in these patients is a nonbacterial verrucous valvular lesion, known as Libman–Sacks endocarditis.

- Hematological Disease: Anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia are significant complications of SLE and/or its treatment. Anemia in these patients is most commonly associated with hemodialysis therapy, while leukopenia results from the immunosuppressive therapies. Thrombocytopenia occurs in up to 25% of patients, with extreme thrombocytopenia (<20,000 platelets per cubic millimeter) occurring in 5–10% of these patients.13

- Mucocutaneous Disease: The cutaneous manifestations of SLE include photosensitive rashes, alopecia (hair loss), periungual telangiectasias (involving the nail folds), and livedo reticularis (purplish networking discoloration of skin). The malar or “butterfly rash,” which affects fewer than half of patients, and the discoid rash are the two most characteristic rashes of SLE (see Fig. 1.4).

- Oral Conditions: Over 75% of SLE patients have oral complaints including ulcerations, xerostomia, and burning mouth. Ulcerations, erythema, and/or keratosis, commonly affecting the vermilion, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and palate found in patients with SLE may be confused with lichen planus.

- Musculoskeletal Conditions: Arthralgia with “morning stiffness” is the most common initial manifestation of SLE, and over 75% of patients develop a true arthritis that is symmetric, nonerosive, and usually involves the hands, wrists, and knees. Involvement of the temporomandibular joint has been documented in up to 60% of SLE patients.

- Neuropsychiatric Disease: Diffuse and focal cerebral dysfunction including psychosis, seizures, cerebrovascular accidents, and peripheral sensorimotor neuropathies account for greater than 60% of neuropsychiatric manifestations.

RA

Affected joints show inflammation with swelling, tenderness, warmth, and decreased range of motion (ROM). Atrophy of the interosseous muscles of the hands is a typical early finding. Joint and tendon destruction may lead to deformities such as ulnar deviation, boutonniere and swan-neck deformities, hammer toes, and, occasionally, joint ankylosis. Common joint physical findings include stiffness, tenderness, pain on motion, swelling, deformity, and limitation of motion.

Extra-articular manifestations include:

- rheumatoid nodules;

- peripheral neuropathy (affects nerves, most often those in the hands and feet, and can result in tingling, numbness, or burning);

- anemia;

- scleritis (inflammation of the blood vessels in the eye that can result in corneal damage, scleromalacia, and, in severe cases of nodular scleritis, perforation);

- infections (patients with RA have a higher risk for infections; immunosuppressive drugs further increase that risk);

- osteoporosis (more common than average in postmenopausal women with RA; the hip is particularly affected; risk for osteoporosis appears to be higher than average in men with the disease who are older than 60);

- heart disease (RA can affect blood vessels and increase the risk for coronary ischemic heart disease);

- SS;

- lymphoma and other cancers (RA-associated immune system alterations may play a role).

PBC

Fatigue is the first reported symptom, with 10% experiencing severe pruritus of unknown cause. Right upper quadrant discomfort occurs in 8–17% of patients.14 Physical examination findings depend on the stage of the disease. In the early stages, examination findings are normal. As the disease progresses, the following may be found:

- hepatomegaly;

- hyperpigmentation;

- splenomegaly;

- jaundice;

- Sicca syndrome (xerophthalmia, xerostomia);

- signs of advanced liver disease are spider nevi, palmar erythema, ascites, temporal and proximal muscle wasting, and peripheral edema.

FM

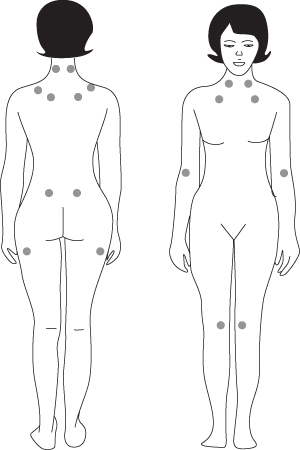

Patients may complain of chronic widespread pain lasting more than 3 months, fatigue, poor sleep, stiffness, cognitive difficulties, multiple somatic symptoms, anxiety, and/or depression. Except for painful tender (or trigger) points and, perhaps, signs of deconditioning, physical examination findings are normal in patients with FM. The tender-point examination should be performed first during the physical examination, because a number of factors may influence the sensitivity of the tender points during the examination. Pain, not just tenderness, is present at multiple FM tender points (see Fig. 10.4).15

Figure 10.4 Location of the nine paired tender points that make up the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia.

Source: NIAMS. Available at: http://www.niams.nih.gov/HealthInfo/Fibromyalgia/default.asp.

PSS (Scleroderma)

Skin symptoms of scleroderma may include:

- fingers or toes that turn blue or white in response to hot and cold temperatures;

- hair loss;

- skin hardness;

- skin that is abnormally dark or light;

- skin thickening, stiffness, and tightness of fingers, hands, and forearm;

- small white lumps beneath the skin, sometimes oozing a white substance that looks like toothpaste;

- sores (ulcers) on the fingertips or toes;

- tight and mask-like skin on the face (see Fig. 1.5).

Bone and muscle symptoms may include:

- joint pain;

- numbness and pain in the feet;

- pain, stiffness, and swelling of fingers and joints.

Breathing problems may result from scarring in the lungs and can include:

- dry cough;

- shortness of breath.

Digestive tract problems may include:

- constipation/diarrhea;

- difficulty swallowing;

- esophageal reflux or heartburn.

SS

Most individuals with SS present with Sicca symptoms, such as xerophthalmia (dry eyes), xerostomia (dry mouth), and parotid gland enlargement (see

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses