Surgery of the anterior mandible

![]() Additional illustrations can be found on the companion website at www.blockdentalimplantsurgery.com

Additional illustrations can be found on the companion website at www.blockdentalimplantsurgery.com

Placement of two to five implants in the anterior mandible

General considerations

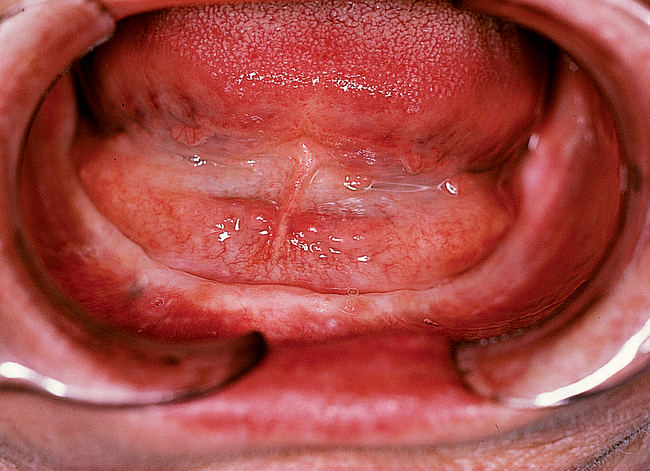

Evaluation of anatomy—physical examination of the patient without teeth

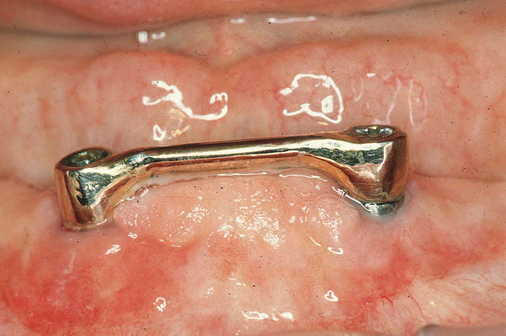

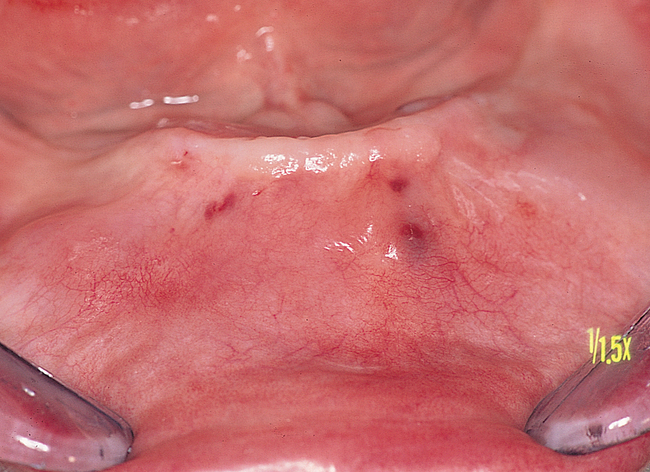

The soft tissue attachments of the floor of the mouth and the mentalis musculature are noted. The width of the band of keratinized gingiva (KG) on the alveolar crest is documented. The distance from the crest to the junction of the attached and unattached mucosa is recorded (Figure 1-1). Examination of the soft tissues is important to determine the need for vestibuloplasty, either before or at the time of implant placement.

Evaluation of anatomy—radiologic examination of the patient without teeth

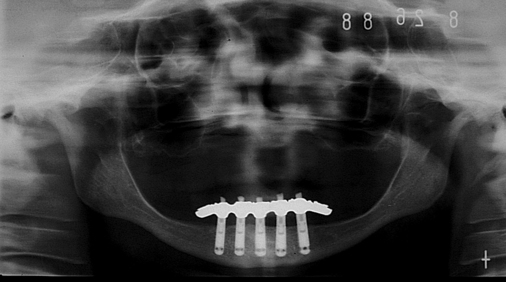

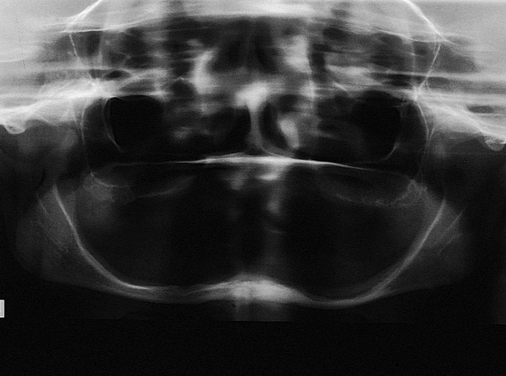

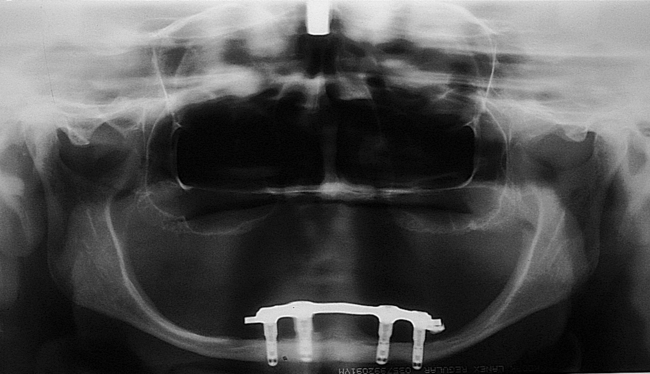

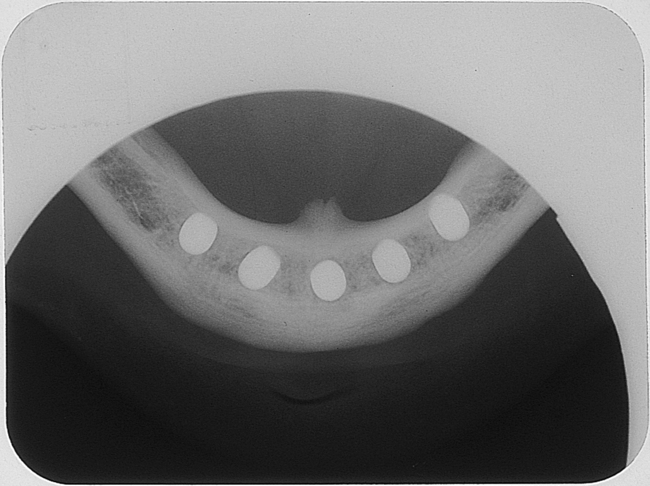

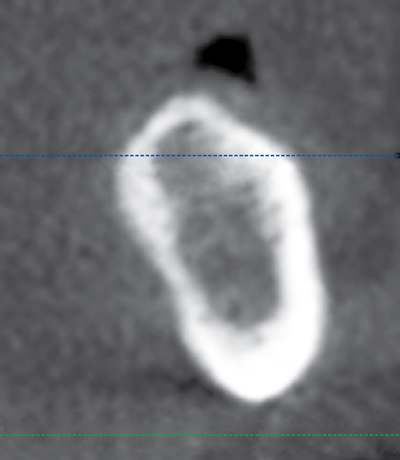

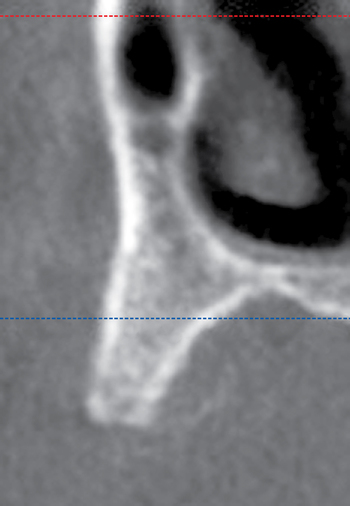

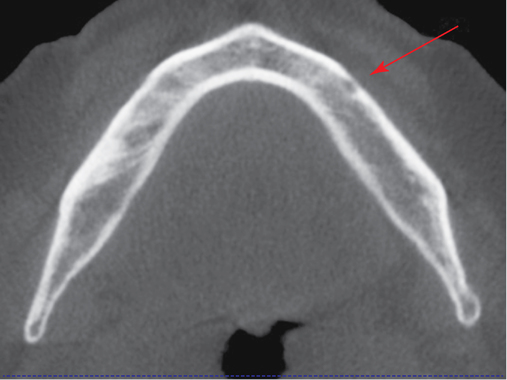

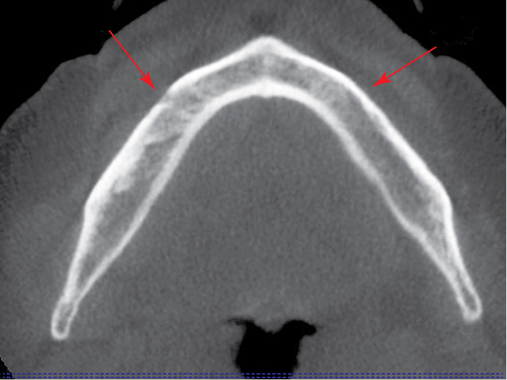

A cone-beam scan is very useful to determine the specific anatomical morphology of the mandible. This scan will show the slope of the cortices, location of the mental foramen, course of the nerve as the nerve enters and exits the mandible from the foramen, and amount of bone present posterior to the foramen. The typical cone-beam scan generates four different frames of reference. One frame contains the lateral and frontal cephalograms of the patient; the second frame contains the axial, frontal, and sagittal slices; the third contains views of the condyle and glenoid fossa; and the fourth are cross-sections from a panoramic-type image (Figure 1-2).

Axial views of the mandible are useful to determine the course of the nerve. By moving through these axial images, one can see the course of the nerve and understand the forward extent of the loop (see Figure 1-2, A, E, F). Each patient is unique, and this view helps avoid nerve injuries. The frontal projections can be used to assess presence of disease in the nasal and sinus regions. This is useful to understand potential problems and general health of the patient. An increase in dimension of the nasal membrane is found in patients with allergies to environmental material. Sinus membrane thickening is often found in patients with poor maxillary dentition. Obliterated sinuses may need treatment by the patient’s otolaryngologist to achieve health.

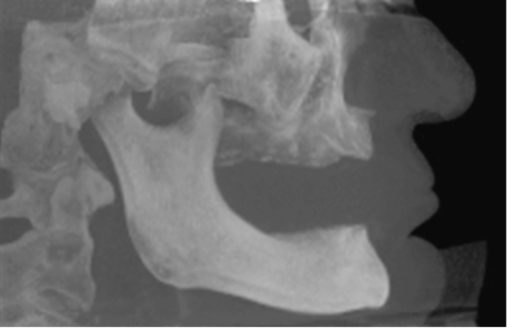

Cone-beam scanners have the capability to generate panoramic reconstructions. On the edentulous mandible, a spline is drawn on the axial view, and cross-sectional images are generated perpendicular to the spline. These cross-sections show the specific anatomy of the anterior mandible (see Figures 1-1 and 1-2). They are used to identify the planned angulation of the implants and whether the planned angulation parallels the labial or lingual cortices. The surgeon can then follow the specific cortical bone to guide implant placement by following the planned orientation using well-defined anatomical landmarks. In a class III mandible, one would angle the implants more posteriorly, often following the lingual cortex of the symphysis. The specific length and diameter of implants to be placed is accurately determined from the cone beam scan, with accuracy reported to within 0.5 mm of the measurements from the scan. This is in contrast to up to 20% magnification error from using traditional panoramic scans.

Surgical treatment for placing implants in the mandible

Incision design considerations.

At the consultation visit, the surgeon notes the following when examining the patient:

1. Level of junction of attached and unattached gingiva

2. Level of attachment of mentalis muscle to the alveolar crest

3. Width of attached KG on the alveolar crest

4. Position of the genial tubercles in relation to the alveolar crest

5. Inclination of the lingual and labial cortical plates of bone

6. Skeletal relationship of the anterior mandible to the maxilla

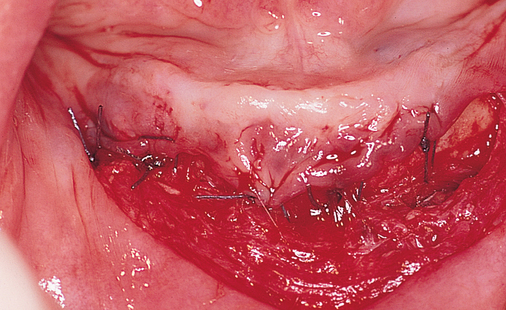

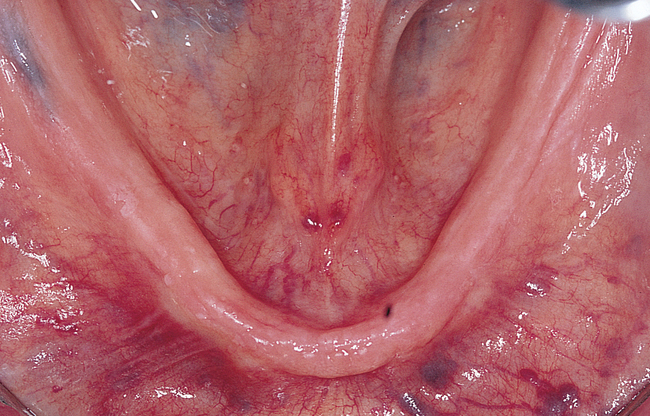

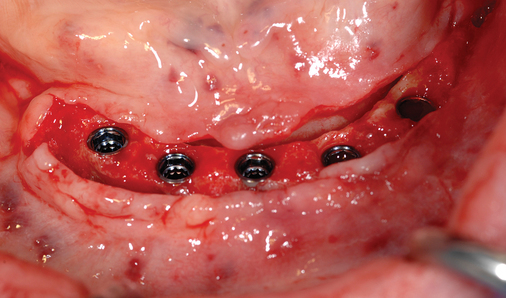

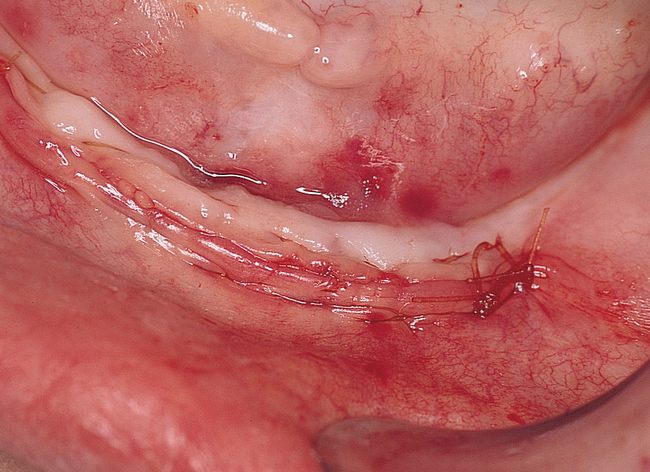

If the attachment of the mentalis muscle is 3 mm or more labial to the location of the attached gingiva on the alveolar crest, a crestal incision can be used (Figures 1-3 and 1-4). If the mentalis muscle is located adjacent to the alveolar crest, which would result in mobile, unattached gingiva directly against the implant abutment when restored, a vestibular incision is used. A type of lipswitch vestibuloplasty (Figure 1-5) is performed to reposition the muscle attachments inferiorly, resulting in nonmobile tissue on the labial surface of the implant abutment complex.

Vestibular incision and dissection.

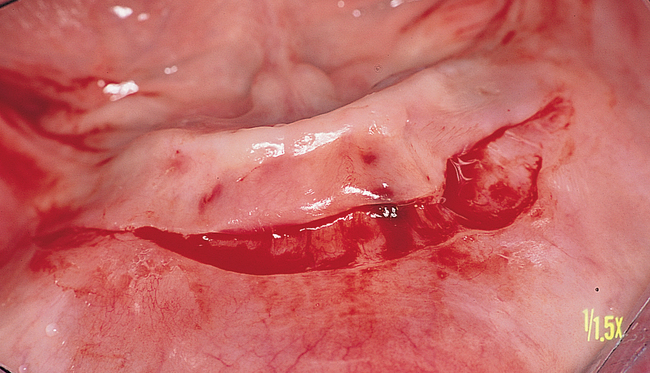

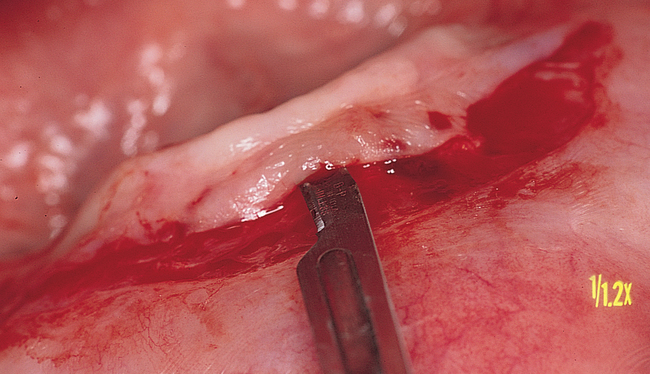

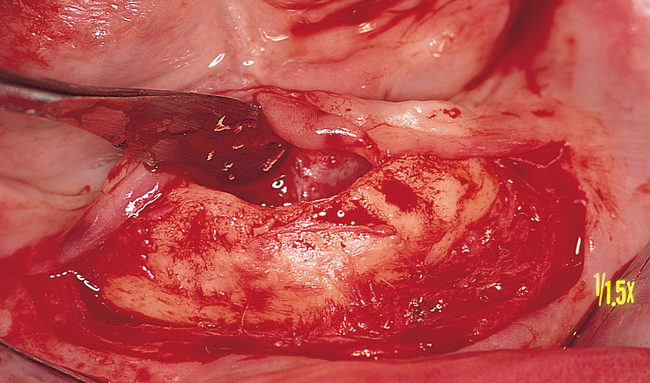

Vestibular incision and dissection is the approach recommended to relocate the mentalis muscle from the alveolar crest, anticipating the ultimate location of the prosthesis and abutments (see Figure 1-5). The incision typically is placed 5 to 10 mm from the junction of the attached and unattached gingiva. The incision is made through mucosa, not into the underlying muscle. The incision extends from the approximate location of the mental foramen in the vestibule. The incision is made with a #15 scalpel blade and is kept superficial to identify branches of the mental nerves. Direct visualization of the branches of the mental nerve allows a meticulous dissection superficial to these nerves and prevents paresthesia.

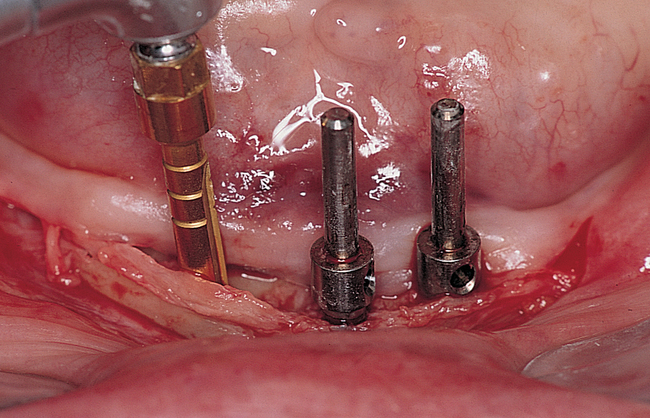

Placement of implants.

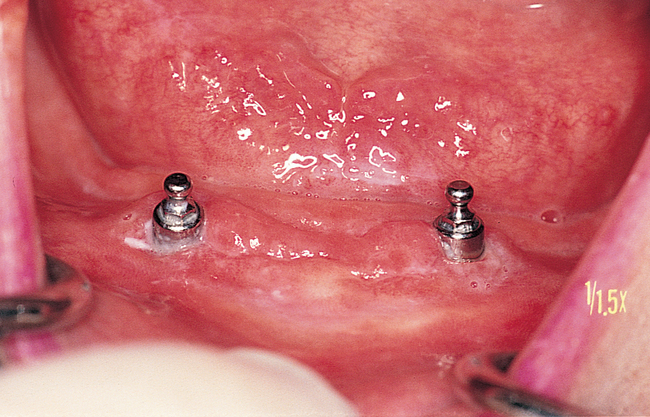

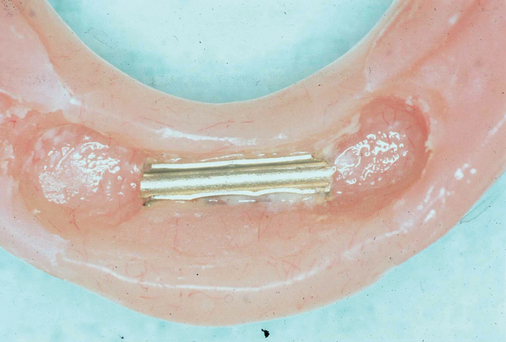

Two implants.

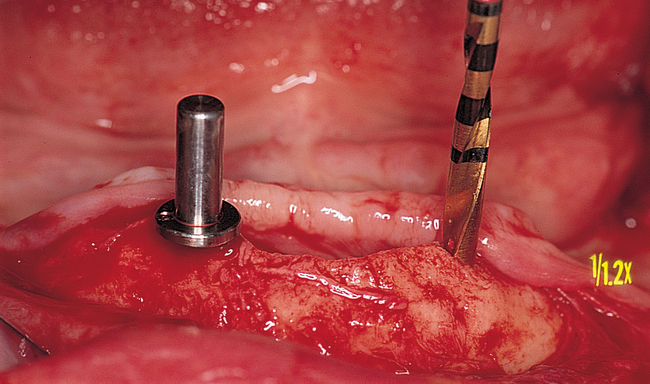

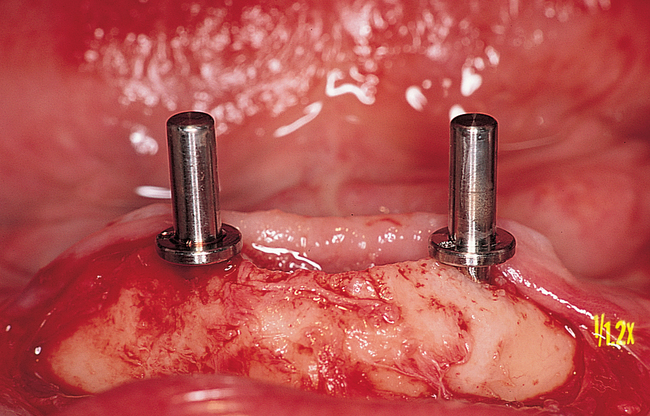

In general, when two implants are to be placed for an overdenture, the surgeon should consider the potential need for additional implants at a later time; for example, the patient may decide to change from a tissue-borne prosthesis to an implant-borne prosthesis. Some patients prefer the overdenture prosthesis, but they may complain of food being caught under the denture and the mobility of the prosthesis when they are speaking, swallowing, or chewing. They also may want to eliminate the need to change clips or O-rings. For patients who desire the retention of a fixed or fixed-removable prosthesis, two or three additional implants may be placed, resulting in four or five implants in the anterior mandible, which will sufficiently support an implant-borne prosthesis. In light of this consideration, when placing two implants into the anterior mandible, the surgeon locates the implants 20 mm apart, each 10 mm from the midline of the mandible, to allow for later implant placement if needed. A caliper is set at 20 mm, and these locations are marked with rongeur forceps or a round bur (see Figures 1-4 and 1-5).

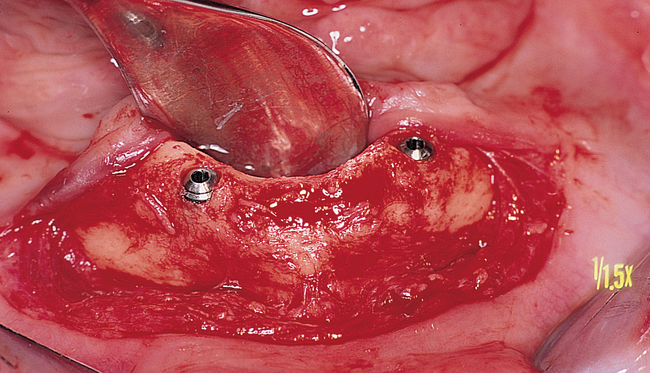

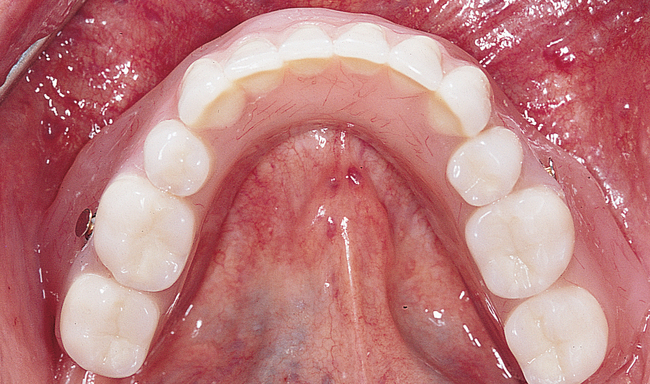

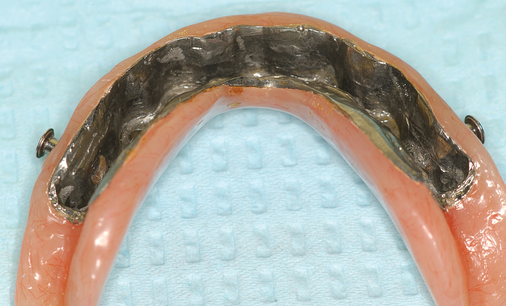

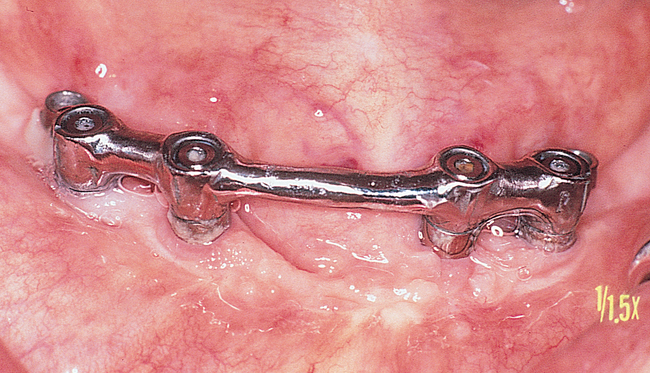

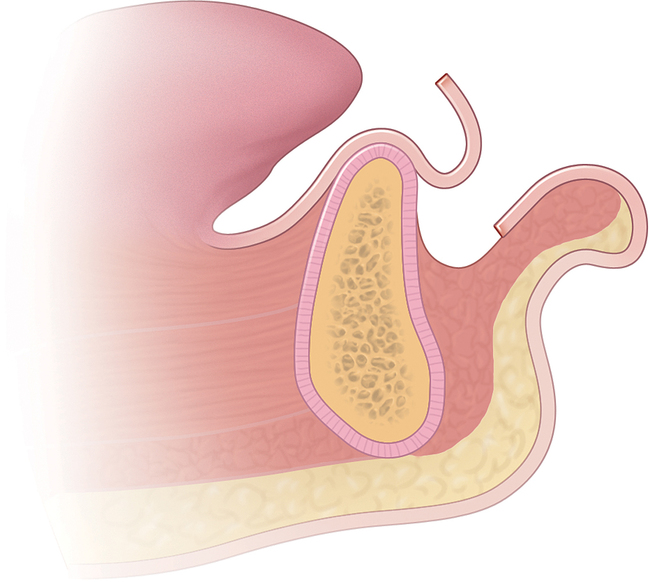

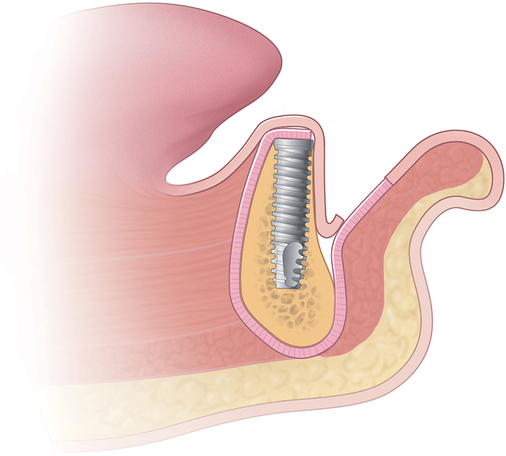

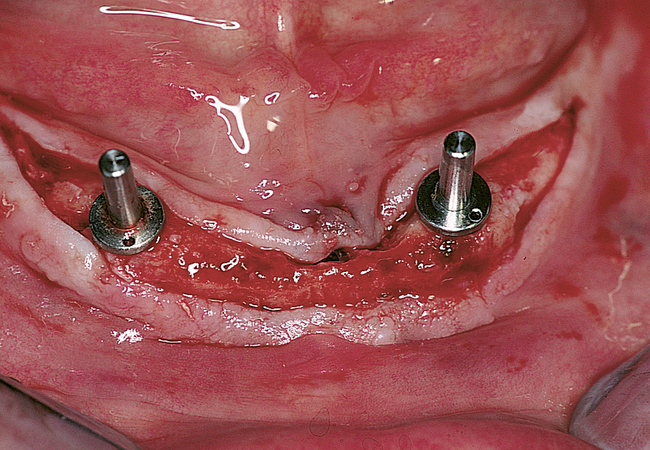

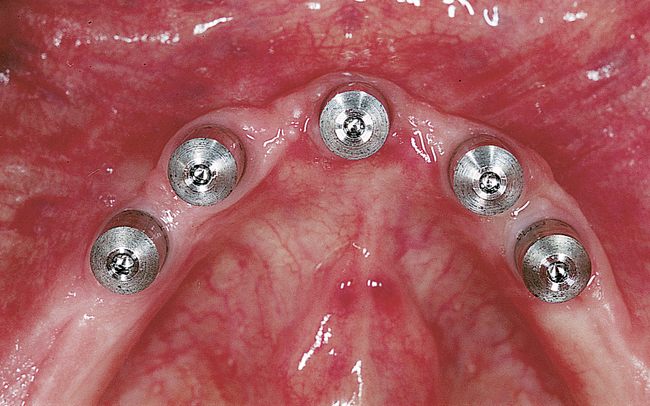

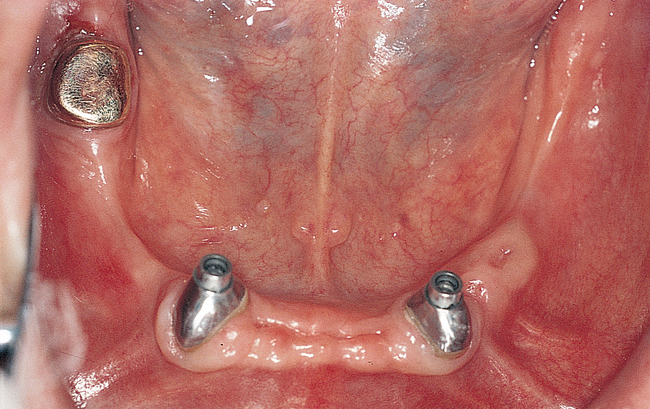

The labiolingual location of the implants in the crest is critical to the patient’s long-term comfort. The implants must be located so as to prevent soft tissue irritation, which can occur if the implants are placed too lingual into the mobile tissue of the floor of the mouth or too labial, causing the mobile mentalis musculature to rub continually against the abutments of the implants, creating chronic problems. Ideal placement of the implants, in the center of the crest, is essential to ensure that the restoration is comfortable for the patient (Figure 1-6 and e-Figure 1-1).

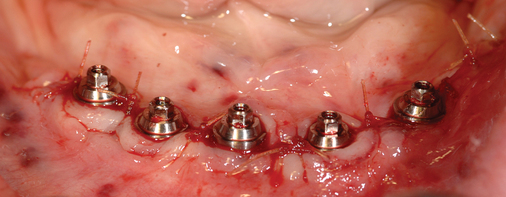

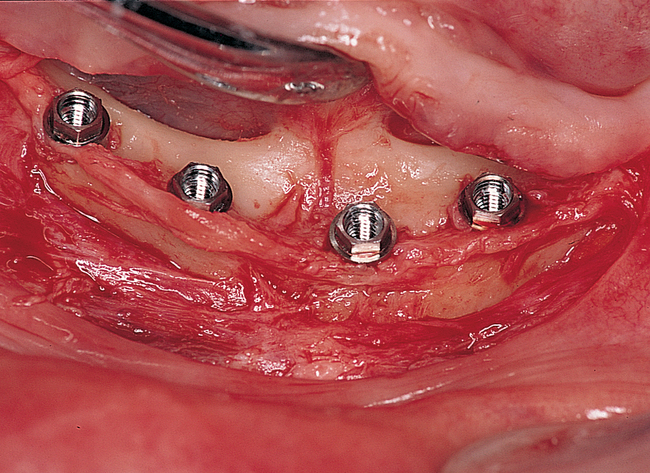

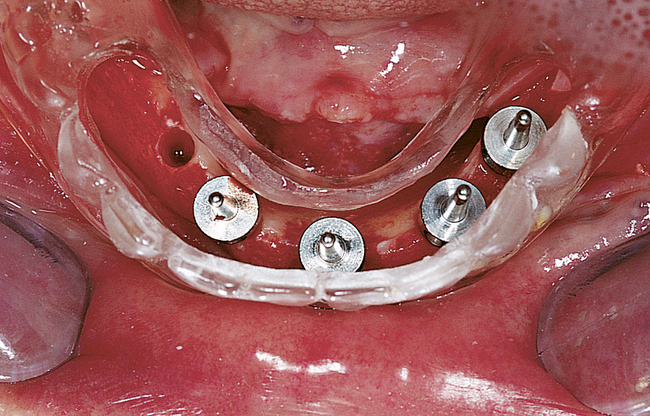

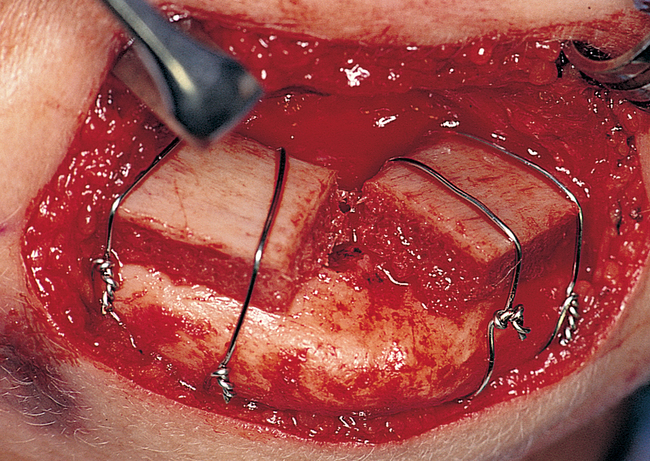

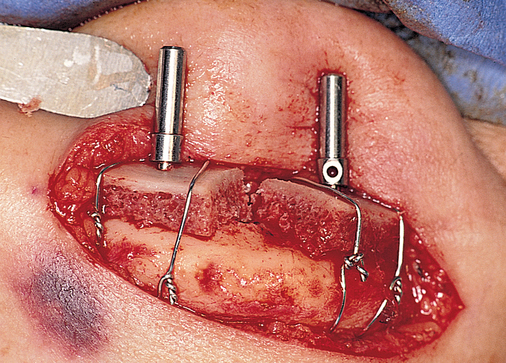

Four or more implants.

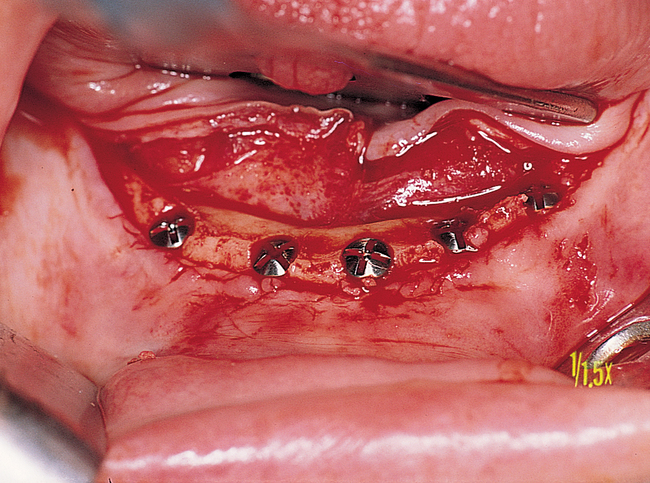

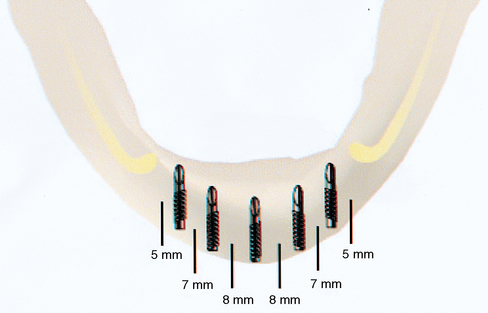

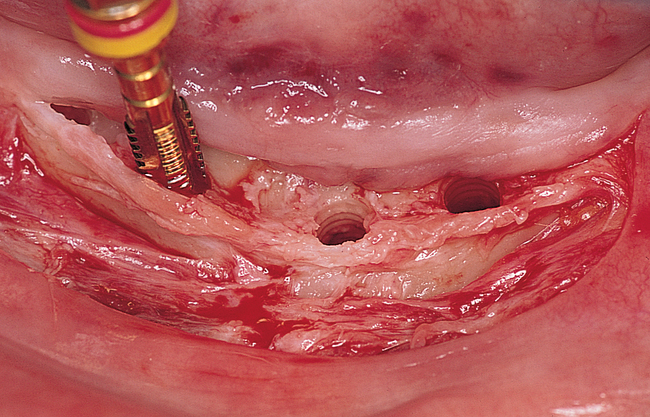

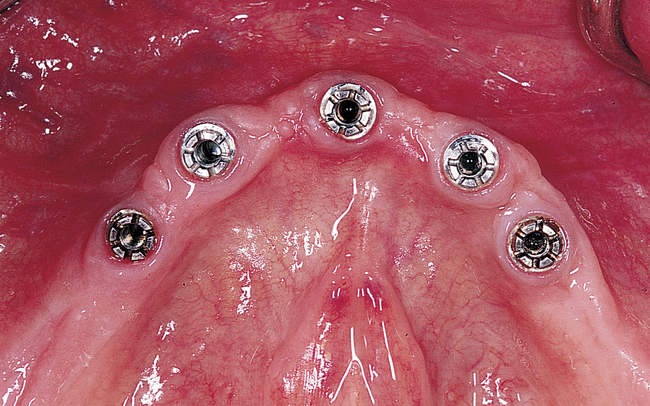

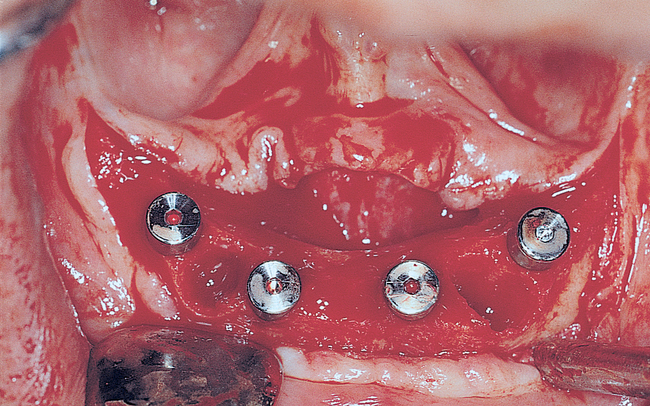

A small, round bur is used to make a depression in the bone to locate the implant site on one side of the mandible. A similar mark is placed on the opposite side of the mandible no less than 5 mm anterior to the mental foramen. The caliper then is set to 7 or 8 mm, and the next implant locations are marked in a similar manner anterior to the two distal locations. If a fifth implant is to be placed, a mark is made in the midline of the mandible. Using the caliper, the surgeon places the implant bodies a sufficient distance apart to ensure adequate space for restoration and hygiene (Figure 1-7; see the companion site for the complete case). For 4-mm-diameter implants, 7 mm of space center to center results in 3 mm of distance between the bodies of the implants.

Common clinical situations.

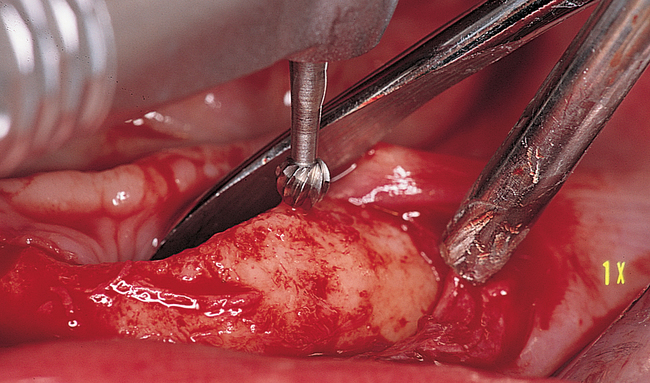

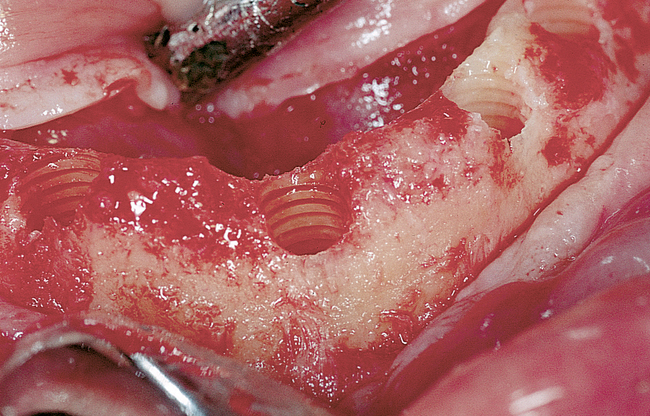

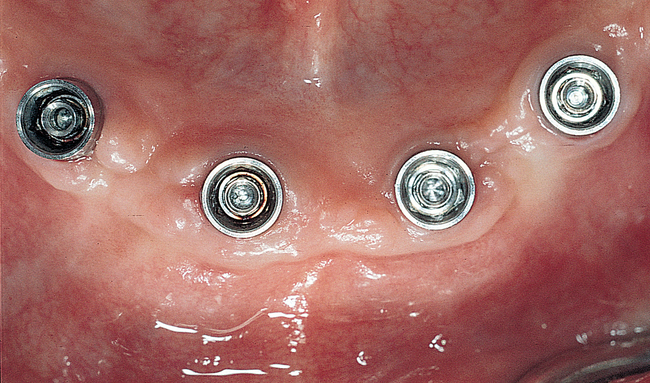

Dissection of the periosteum may be tedious weeks when performed after extractions, especially if the extractions involved a few remaining teeth (e.g., only the canines). The soft tissue invaginations into the extraction sites must be carefully elevated without tearing the flap. The crestal bone irregularities are reduced to ensure that all implants exit the crest at the same vertical level. Canine teeth may be larger than the diameter of the implant. In these cases, the bone height may have to be reduced, a larger-diameter implant may need to be placed, or defects between the implant and the remaining bone may need to be grafted. Reducing the bone with a rongeur forceps is a simple method of dealing with this problem. The implants also may need to be countersunk an additional 1 to 2 mm because of expected crestal bone loss from normal remodeling of the extraction site (Figure 1-8; see the companion site for the complete case).

Prior hydroxylapatite augmentation.

Patients who have had previous hydroxylapatite (HA) augmentation can receive implants (e-Figure 1-2). The preoperative evaluation of these patients should attempt to determine the amount of native bone inferior to the HA. If more than 10 mm of native bone is present, the HA can be removed if it is not impregnated with bone. If the HA ridge augmentation was performed 5 or more years before the proposed implant surgery, the HA ridge may be totally encased in bone. If the HA augmentation is more recent, the HA particles may be removed easily because mostly fibrous tissue will be holding the particles in place.

Augmentation of the atrophic mandible

General considerations

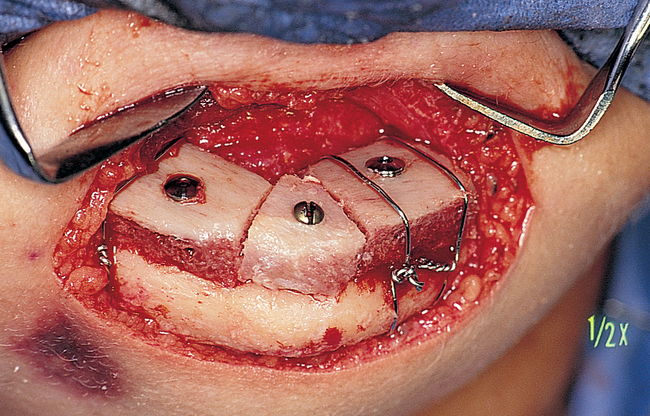

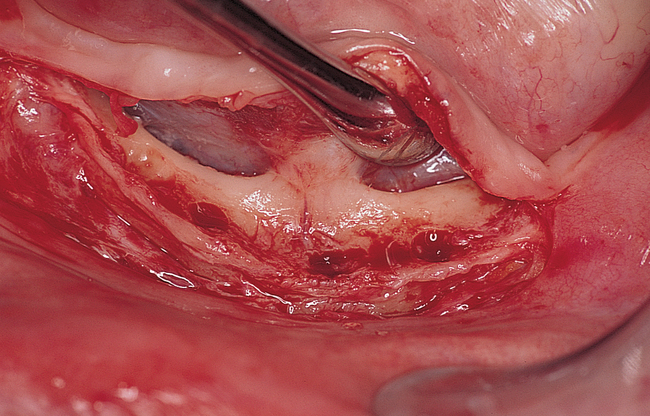

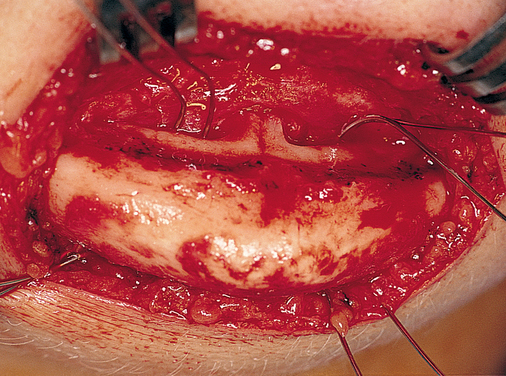

Extraoral incision and placement of autogenous corticocancellous bone grafts

The disadvantages of using an extraoral approach are scarring and difficulty placing implants at the time of graft placement. Most implants are flared to the labial when placed into a bone graft performed through an extraoral incision. The advantages of using an extraoral approach to graft the atrophic mandible are (1) prevention of intraoral incision breakdown; (2) prevention of an intraoral communication with the bone graft and potential infection; (3) maintenance of the vestibular attachments, which may eliminate the need for vestibuloplasty; and (4) ease of reflection of the inferior alveolar nerve from the alveolar crest without incising over the nerve (Figure 1-9).

Placement of implants into the atrophic mandible without grafting

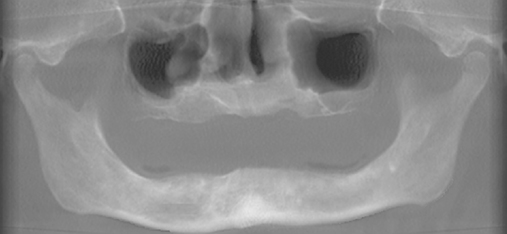

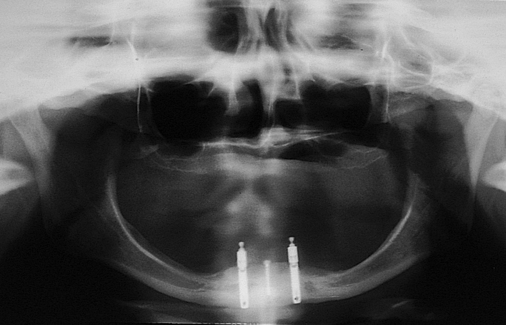

Patients with atrophic mandibles with 5 to 6 mm of bone height but less than 10 mm may not be healthy and thus not candidates for bone grafting because of health-related issues. For these patients, four implants can be placed, with 2 mm of the implant through the inferior border of the mandible and, as necessary, 2 mm supracrestal. It is important to prepare the bone gently and to pretap the implant sites because the mandible may be brittle, have minimal blood supply, and are prone to fracture. The implants should be placed so as to avoid labial protrusion. Long-term follow-up of this method indicates excellent results, with anecdotal evidence that bone formation can occur distal to the implants, presumably in response to tensile and compressive forces on the mandible (Figure 1-10).

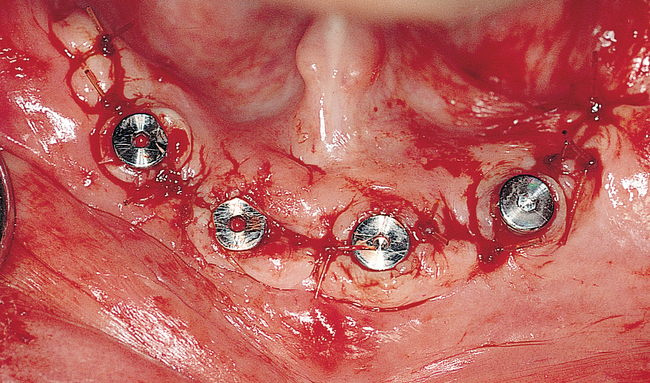

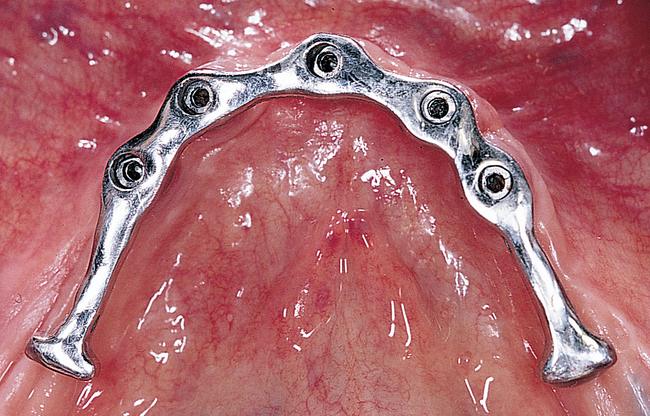

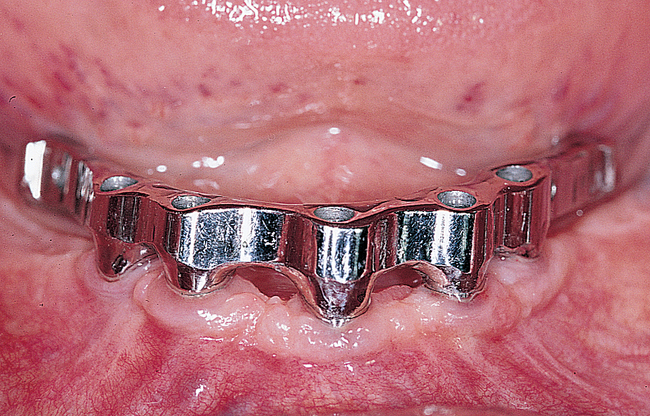

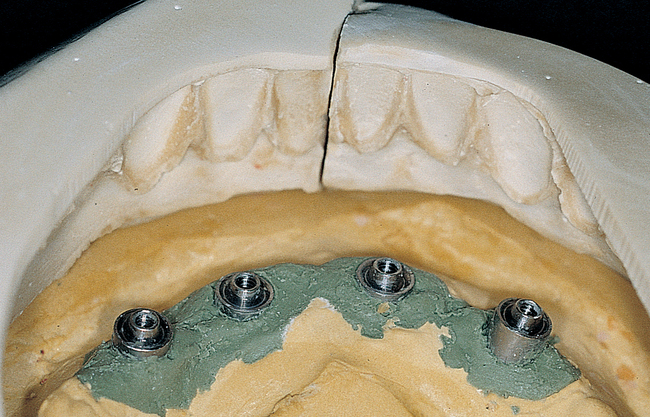

Immediate loading of the edentulous mandible

Restoration of the edentulous mandible has been achieved with the use of dental implants and a variety of prostheses that are removable by the patient, removable by the dentist, or fixed in position by cement. For dental implants, the traditional two-stage placement with a stress-free healing period and secondary exposure surgery has been well documented.1–3 When two-stage implant systems are used, with primary gingival closure after implant placement, interim relined dentures are used to restore function for up to 6 months. However, the first several weeks after implant placement are uncomfortable for patients and limit their function during the entire implant integration period. To minimize the patient’s discomfort and functional disability, treatment options using immediate implant-borne prostheses have been developed. The decision to provide the patient with improved function immediately after implant placement is patient driven. The overall success rate for immediate rehabilitation of the edentulous patient is similar to that for the traditional two-stage method.4–7

A clinician’s decision about whether to rehabilitate an edentulous patient or a patient who requires that all of his or her teeth be removed immediately is made based on evidence that this method is as successful as traditional delayed techniques. Clear evidence has justified immediate loading of implants placed between the foramina of the edentulous mandible.4–17

The initial reports on immediate loading of mandibular implants used extra or expendable implants that were placed into function with a temporary fixed restoration at surgery.18 The immediately loaded implants integrated. Following the same approach, Schnitman et al.6 later reported failure of four of 28 implants; these four implants were placed in the posterior mandible and were 7 mm long. Tarnow et al.5 used a provisional approach to restore six mandibles and four maxillas. They reported a high rate of success, with 67 of 69 loaded implants integrating. All of these loaded implants were cross-arch stabilized immediately upon placement to reduce the isolated load on a single implant; the cross-arch connection disperses the load to all the implants.

To minimize treatment time, the final prosthesis can be delivered on the day or within days of the surgery. Brånemark et al.7 used three implants in the anterior mandible and a screw-retained hybrid prosthesis; they reported a 92% to 98% success rate.

Table 1-1 summarizes classic papers on the immediate loading of mandibular implants; these reports verify that sufficient evidence exists that this procedure is acceptable and no longer should be considered experimental. The 14 authors listed results of 240 mandibles involving more than 1277 implants, all supporting immediate restoration of the mandible. The success rates ranged from 84.7% to 100%, indicating that immediate loading of the edentulous mandible is a viable treatment. The lower success rates from Balshi and Wolfinger4 and Schnitman et al.6 have clear explanations for the failures. The remaining references report success rates greater than 95% in the mandible.5,7–17 The reasons cited for implant failure in immediate loading of the edentulous mandible include placement of short implants into the posterior mandible, bruxism, poorly fitting prostheses, poor surgical technique, and infection of the implants.18

TABLE 1-1

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses