1

Medically Compromised Patients

Case 1

Congenital Heart Disease

Figure 1.1.1 Facial photo

A. Presenting Patient

- 2-year-, 8-month-old Hispanic female

- New patient

B. Chief Complaint

- Referred from hospital pediatric cardiac unit for dental assessment and management of asymptomatic dental caries

C. Social History

- Single mother is primary caregiver and receives welfare

- No siblings

D. Medical History

Congenital Heart Defects

- Triscuspid atresia

- Hypoplastic right ventricle

- Restrictive ventricular septal defect (VSD)

- Sub-pulmonary narrowing

No Known Food or Drug Allergies

Current Medications

- Warfarin po 3 mg daily

- Furosemide po 20 mg daily

Several Past Surgeries and Hospitalizations

- Incidence rate of approximately 8 to 10 cases/1,000 live births

- Most lesions occur individually; several form major components of syndromes or chromosomal disorders such as Down (trisomy 21) and Turner syndrome (XO chromosome)

- Known risk factors associated with CHD include maternal rubella; diabetes; alcoholism; irradiation; and drugs such as thalidomide, phenytoin sodium (Dilantin) and warfarin sodium (Coumadin)

- Turbulent blood flow is caused by structural abnormalities of the heart anatomy and presents clinically as an audible murmur

- CHD can be classified into acyanotic (shunt or stenotic) and cyanotic lesions depending on clinical presentation

- Acyanotic lesions are characterized by a connection between the systemic and pulmonary circulations or stenosis of either circulation (left to right shunts). The most common anomalies are:

- All cyanotic conditions exhibit right to left shunting of desaturated blood. Infants with mild cyanosis may be pink at rest but become very blue during crying or physical exertion. Children with cyanotic defects are at significant risk for desaturation during general anesthesia

- The most common cyanotic lesions are:

- If cardiac failure develops, the infant is digitalized and prescribed diuretics if necessary. Hospitalization, oxygen, nasogastric tube feeding, and antibiotic therapy for chest infection may also be required

E. Medical Consult

For This Patient (see Fundamental Point 1):

- Baseline cardiac function

- Baseline INR range: 2.0 to 3.0

- Baseline hemoglobin: 11.7 g/dl

- Baseline pulmonary saturations: 97%

- Baseline blood pressure 80/40 mm Hg

- Baseline respiratory rate: 20/minute

- Baseline oxygen: 0.5 l/minute

- Blood pressure

- Respiratory rate

- Oxygen rate

- Pulmonary saturations

- Blood gases

- Assess risk of cardiac complications under general anesthesia (GA)

- Assess risk of infective endocarditis (IE) and need for antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures

- Assess risk of hemorrhage during dental surgery

- Develop a perioperative anticoagulant management plan

F. Dental History

- No dental home

- Currently bottle feeding with sweetened liquids

- High caloric supplementation to increase weight

- Toothbrushing once a day with fluoridated toothpaste with little adult supervision

- No systemic fluoride exposure

- No history of dental trauma

G. Extra-oral Exam

- No significant findings

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- Generalized erythematous mucosa

- Generalized edematous gingivae

Hard Tissues

- Proximal and smooth surface cavitations on maxillary incisors

- Fissure cavitations on molars

- Smooth surface demineralization on molars

Occlusal Evaluation of Primary Dentition

- Flush terminal plane

- Anterior open bite

Generalized Severe Plaque Accumulation

I. Diagnostic Tools

Bacteriology and Saliva Tests

- Not done

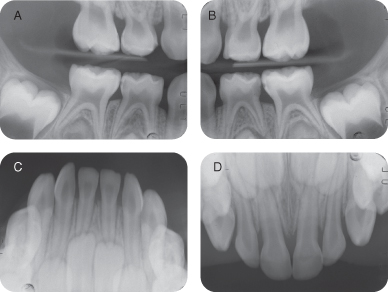

Radiographs

- Intra-oral periapical films (taken at time of dental treatment under general anesthesia)

Photographs

- Pre- and post-operative intra-oral photos (taken at time of dental surgery)

High Caries Risk Due to (Caries-risk Assessment Tool [CAT]) (see Fundamental Point 2):

- Special health needs child

- Visible cavitations

- Enamel demineralizations

- Low socioeconomic status

- Visible plaque score (4/6)

- Dietary chart (>3 sugar exposures/day)

- Medications that impair saliva flow

- Use of fluoridated toothpaste but no fluoridated water nor fluoride supplements

- Toothbrushing once a day

- Visualize child’s teeth

- Access reliable historian for nonclinical elements

- Be familiar with footnotes that clarify elements

- Understand that each child’s risk classification is determined by highest risk category where a risk indicator exists

- Caries risk assessed at one point in time only

- Clinical management remains a professional decision

- CAT does not render a diagnosis

- Advanced technologies (e.g., Diagnodent, microbiological tests) are not essential for using this tool

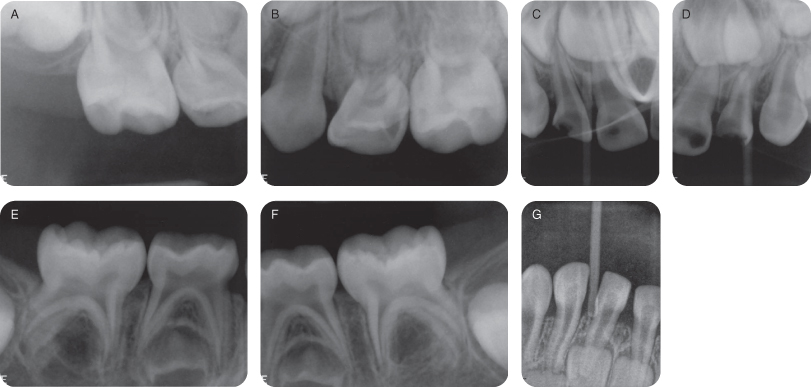

Figure 1.1.2a–g. Pre-op intra-oral radiographs

Figure 1.1.3a–e. Pre-op intra-oral photographs

Figure 1.1.4a–e. Post-op intra-oral photographs

J. Differential Diagnosis

Developmental

- Enamel hypoplasia/hypomineralization

Infective

- Bacterial and/or fungal

Odontogenic

- Loss of tooth structure due to dental caries and/or attrition/abrasion/erosion

Inflammatory

Pulpal Pathology

K. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Active early childhood caries

- Chronic hyperplastic gingivitis

- Periapical pathology

- Enamel hypoplasia

Problem List

- Untreated carious lesions

- Malocclusion

- Poor infant feeding practice

- Parent’s limited understanding of potential medical complications

- High risk of infective endocarditis (IE)—see Background Information 2

- High risk of uncontrolled hemorrhage from invasive dental procedure

- Behavior assessment: uncooperative

- Both coronary heart disease (CHD) and rheumatic heart disease can predispose the scarred internal lining of the heart to bacterial or fungal infection known as infective endocarditis (IE)

- Bacteremia during or after an invasive dental procedure can lead to the formation of friable vegetations of blood cells and organisms on the scar tissue

- Streptococcus viridans is most frequently responsible for chronic IE, while Staphylococcus aureus is often implicated in the acute fulminating form (Hallett 2003)

- IE may be prevented by antibiotic prophylaxis but there is little or no evidence to support this practice

- In 2008, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK recommended against IE prophylaxis for all patients undergoing any type of dental procedures. Despite a 78.6% reduction in the number of prescriptions in the two years after the guideline was introduced, there was no large increase in the incidence of cases of or deaths from IE

- Pre-operative antiseptic mouthwash can reduce oral bacterial load

- Focusing on good oral hygiene practices may be more important than antibiotic prophylaxis

- Anticoagulants are usually prescribed for children with valvular heart disease and prosthetic valves to reduce the risk of embolization

- If dental extractions are required, it may be necessary to decrease the clotting times to facilitate adequate coagulation but not to such an extent so as to cause emboli or clotting around the heart valves

- Commonly used anticoagulant drugs are oral warfarin sodium (Coumadin), which is a vitamin K antagonist depleting factors II, VII, IX and X, or heparin sodium (Heparin), which inhibits factors IX, X, and XII

- Local hemostatic measures include application of topical thrombin, packing of the socket with microfibrillar collagen hemostat, oxidized regenerated cellulose, and suturing of attached gingivae. Splints or stomo-adhesive bandages may also be of benefit. There have been recent reports of the efficacy of a “fibrin sealant” (Tisseel Duo 500) in the management of coagulopathies, but its use on moist oral mucosa is limited

- It is recommended to consult the cardiologist regarding modification of the anticoagulant therapy before oral surgery. Some practitioners cease warfarin three to five days prior to the surgery date, commence enoxaparin sodium once daily via Insulfon, and admit the patient to the hospital on the day of the procedure. In this protocol, recommencement of warfarin and weaning of enoxaparin sodium 24 hours after surgery is required to re-establish correct international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)

- However, recent studies on adults who had multiple dental extractions without modification of their anticoagulant therapy showed few or no post-operative complications. The American Dental Association stated in 2003 that the scientific literature does not support routine discontinuation of oral anti-coagulation therapy for dental patients because it can place them at unnecessary medical risk. Their coagulation status, based on the INR, must be evaluated before invasive dental procedures are performed and any changes in their anticoagulation therapy must be discussed with the patient’s physician.

- The American College of Chest Physicians recommends that patients who are taking vitamin K antagonists and are about to undergo minor dental procedures continue with the therapy because it does not confer an increase in clinically important major bleeding. The 2008 College guidelines further state that it is reasonable to co-administer an oral pre-hemostatic agent at the time of the procedure until more adequately powered studies are done. In patients receiving aspirin, the College recommends continuing it around the time of the procedure.

- To date, there have been no studies on pediatric patients, only case reports.

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

Establishment of a Dental Home and Caries Prevention Plan

- Cease bottle feeding

- Improve and increase frequency of oral hygiene

- Limit sugar intake between meals

- Brush after oral medicine intake

- Commence 1 mg fluoride supplement daily

Caries Control Using 0.2% Chlorhexidine Gel or 0.12% Liquid: Apply With Cotton Tip Nightly Two Weeks Prior to Procedure

Remove Any Potentially/Pulpally Involved Teeth to Reduce Future Risk of Chronic Bacteremia

Comprehensive Treatment of Carious Lesions Under General Anesthesia Due to the Complex Medical History, Dental Needs, and Behavior Management Issues

IE Prevention With IV Antibiotic Prophylaxis.

Perioperative Anticoagulant Plan

Follow-up Care

Post-op and Home Care Instructions

- Discharge after recommencement of Warfarin

- Soft cold diet for two days

- Recommence tooth brushing after 24 hours

- Start prevention plan

Recall Plan

- Six weeks post-op, and four- to six-month recall thereafter

M. Prognosis and Discussion

- Prognosis for limiting caries progression and changing the diet is guarded in view of limited understanding of caries risk factors and medical complications by parent. Prognosis could be improved with additional home support.

N. Common Complications and Alternative Treatment Plans

- Noncompliance with dietary advice

- Post-operative bleeding or infection

- Continued caries progression

Alternative Treatment Plans May Include:

- Use of stainless steel crowns in all teeth presenting with decalfication or white spot lesions

- Alternative pulpal management, e.g., extraction vs. pulp therapy (must consider risks of chronic bacteremia)

- Alternative medications for anticoagulant management (e.g., Heparin)

- Alternative methods for behavior management

Self-study Questions

1. What important questions need to be asked when taking a medical history from a patient with congenital heart disease?

2. What are some common medications to improve cardiac function and reduce congestive heart failure in children?

3. Why are children with congenital heart disease more likely to develop dental caries in primary teeth?

4. How would non-compliance with preventive advice alter treatment planning?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography and Additional Reading

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2011–2012a.Guideline on Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Reference Manual. Pediatr Dent 33(6):110–17.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2011–2012b.Guideline on Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Dental Patients at Risk for Infection, Reference Manual. Pediatr Dent 33(6):265–9.

Brennan MT, Wynn RL, Miller CS. 2007. Aspirin and bleeding in dentistry: an update and recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 104:316–23. http://www.circulationaha.org, May 8, 2007.

Douketis JD, Berger PB, Dunn AS, et al. 2008. The perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy. American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. 8th ed. Chest 2008; 133:299–339S.

Dunn AS, Turpie AGG. 2003. Perioperative management of patients receiving oral anticoagulants—A systematic review. Arch Intern Med 163:901–8.

Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, et al. 2007. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents. JADA 138(5):652–5.

Hallett KB. 2003. Medically compromised children. In Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry, 2nd ed. AC Cameron, RP Widmer (eds). Mosby: London pp. 234–44.

Jeske AH, Suchko GD. 2003. Lack of a scientific basis for routine discontinuation of oral anticoagulation therapy before dental treatment. JADA 134:1492–7.

Lockhart PB, Loven B, Brennan MT, Fox PC. 2007. The evidence base for the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in dental practice. JADA 138:458–74.

Napenas JJ, Hong CHL, Brennan MT, et al. 2009. The frequency of bleeding complications after invasive dental treatment in patients receiving single and dual antiplatelet therapy. JADA 140:690–5.

Perry DJ, Noakes TJC, Helliwell PS. 2007. Guidelines for the management of patients on oral anticoagulants requiring dental surgery. Br Dent J 203:389–93.

Thronhill MH, Dayer MJ, Forde JM, et al. 2011. Impact of the NICE guideline recommending cessation of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infective endocarditis: before and after study. BMJ 342:d2392.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of Infective Endocarditis—Guidelines from the American Heart Association.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. Nature of diagnosis (acyanotic or cyanotic), supportive medications, previous surgical corrections, future surgical corrections, current cardiac function, physical activity limitations, risk of IE

2. Oral elixirs including Digoxin and Furosemide, usually with sucrose or sorbitol base.

3. Enamel is often hypoplastic and susceptible to early childhood caries; high-caloric diet; use of sucrose-rich medications; medications may induce xerostomia; parental indulgence with sweets, juices, sodas, etc.

4. It may be necessary to extract all carious teeth, especially those with pulpal involvement, to reduce the risk of infection and IE.

Case 2

Cystic Fibrosis

Figure 1.2.1a. Facial photograph

A. Presenting Patient

- 5-year-, 1-month-old female

- New patient

B. Chief Complaint

- Referral by general dentist for dental assessment and treatment of asymptomatic carious lesions

C. Social History

- Mother is primary care provider

- No siblings

D. Medical History

- When was the diagnosis made?

- Who are the lead pediatrician and other pediatricians who are involved in the patient’s care and what are their addresses?

- What is the frequency of outpatient appointments?

- What is the frequency of admissions?

- When were the most recent admissions?

- What are the frequency and severity of chest infections?

- What is the microbiology of chest infections? (Infection by pseudomonas is an indication that lung function is severely compromised.)

- What are the current medications?

- Is an indwelling catheter (central line) present?

- What is the patient’s experience with general anesthesia?

- Is there a possibility of further radical treatment? (Heart-lung transplant may be considered in patients with terminal respiratory failure.)

- Are there any special dietary requirements/modifications?

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) (see Background Information 1)

- Diagnosed at 3 years and 6 months of age

- Sees pediatrician every six weeks

- Has daily physiotherapy for removal of lung secretions

- Last acute chest infection: three weeks ago

No Known Drug or Food Allergies; Vaccinations Up-to-Date

Medications

- Flucloxacillin 250 mg qid: broad-spectrum antibiotic for prophylaxis against chest infections

- Pancreatin with each meal: pancreatic enzyme replacement

- Salbutamol inhaler bid: β-2 agonist

- Fluticasone Propionate inhaler bid: corticosteroid

- Vitamins A, D, and E supplements

- Ursodeoxycholic acid: dietary supplement to improve flow of bile

- Autosomal recessive disorder

- Prevalence 1 in 2,500 live births in Caucasians

- Basic defect is a failure to code for cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) protein which regulates electrolyte and water transport across cell membranes

- The optimal diagnostic test is the measurement of sweat electrolyte levels

- Complex, multisystem disease involving the upper and lower airways, pancreas, bowel, and reproductive tracts. The two main systems affected are respiratory and gastrointestinal.

- Respiratory issues: Viscous secretions accumulate in smaller airways which are prone to infection. Children are on long-term antibiotics to prevent chest infections, which must be treated aggressively. Healing occurs with scarring, further compromising the airway. Regular physiotherapy is required to encourage physical removal of secretions. Many children have reversible airway obstructions treated by salbutamol and steroid inhalers.

- Gastrointestinal issues: Damage to pancreas results in pancreatic enzyme insufficiency, thus oral pancreatic supplements are required with all meals. Fat-soluble vitamin supplements are taken due to the patients’ reduced ability to absorb the vitamins. Incidence of celiac disease and Crohn’s disease seems to be increased in CF patients.

- Long-term complications of CF include diabetes, liver disease, pneumothorax, sinusitis, nasal polyps, osteopenia, failure to thrive, and infertility

- The cornerstones of management include proactive treatment of airway infection and encouragement of good nutrition, as well as an active lifestyle

- For patients in late respiratory failure, heart-lung transplants are an option but are available in only a minority of cases

- In spite of a high-carbohydrate diet the incidence of dental caries in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients has been found to be consistently lower than in healthy controls (Kinirons 1985, Narang, et al. 2003). This fact has been attributed to the long-term antibiotic therapy of these children (Kinirons 1992), high salivary pH (Kinirons 1985), and raised salivary calcium levels (Blomfield, et al. 1973)

- Patients with CF present increased levels of calculus and lower gingival health (Narang, et al. 2003). These patients have altered amounts of calcium and phosphate in their saliva, which affect calculus formation. However, pancreatin may have a role in decreasing calculus formation and reducing dental caries in these patients (Narang, et al. 2003)

- There is a higher prevalence of enamel defects, which can be attributed to severe systemic upset in infancy, especially in cases which patients are diagnosed late

- General anesthetic is strongly contra-indicated because of the compromised airway and increased incidence of post-operative chest infections

- Decisions on which antibiotic to give for acute dental conditions must be made in conjunction with the pediatrician. The choice of antibiotic should take into account the current regime and the types of antibiotics that may be required for future treatment

- Children with CF are high priority for dental prevention because the condition makes treatment of dental disease more difficult

- Liver disease may be a feature of older children with CF, resulting in complications involving bleeding, infection, and drug metabolism

- Nitrous oxide sedation may be contra-indicated in these children and should only be carried out after consultation with the pediatrician to establish respiratory capacity. The procedure should be carried out in a hospital environment. Careful monitoring of oxygen saturation levels is essential

E. Medical Consult

If Parent is Not a Good Historian or if Child is Not Cooperative for Dental Care in Office, Contact Child’s Pediatrician to:

- Review current medications and history of hospital admissions

- Establish respiratory status

- Discuss other means to treat this patient

F. Dental History

- Patient has dental home and has had restorations done in office

- Cariogenic diet

- Good oral hygiene habits with some parental supervision

- Uses toothpaste containing fluoride

- Has non-fluoridated water supply and no fluoride supplementation

- No history of trauma

- Behavior assessment: ± on the Frankl Palmer Scale

G. Extra-oral Exam

- No significant findings

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- No significant findings

Hard Tissues

- No significant findings

Occlusal Evaluation of Primary Dentition

- Mesial step molars

- Right anterior crossbite

- Lower midline shift to the right (3 mm)

- Maxillary anterior crowding

Minimal Plaque Seen on Teeth

Dental Exam

- Severe enamel defects on maxillary left second primary molar and mandibular left second primary molar, which have been restored with amalgam. However, there is evidence of secondary caries at margins now

- Mild enamel defects on mandibular right second primary molar and maxillary right second primary molar; the latter also has occlusal caries

- Evidence of moderate erosion on upper and lower incisors

Figure 1.2.1b. Pre-op frontal intra-oral

Figure 1.2.2. Pre-op maxillary intra-oral

Figure 1.2.3. Pre-op mandibular intra-oral

I. Diagnostic Tools

- Right and left bitewings: no other radiographic lesions noted other than the ones mentioned above.

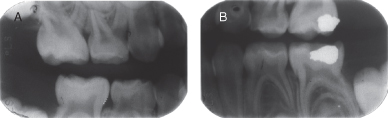

Figure 1.2.4a–b. Pre-op right and left bitewing radiographs

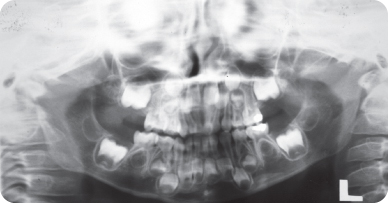

Figure 1.2.5. Pre-op panoramic radiograph

J. Differential Diagnosis

- N/A

K. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Early childhood caries with probable pulp involvement

- Occlusion problems

- Enamel hypoplasia

- Early tooth surface loss in incisors

Problem List

- Untreated carious lesions

- Poor dietary habits

- High caries risk (special health care needs, cariogenic diet, caries)

- Possible behavior management issues

- Correction of malocclusion

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Treatment of all carious lesions

- Establishment of a caries prevention plan

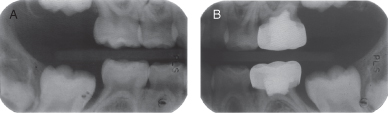

Figure 1.2.6a–b. Post-op right and left bitewing radiographs

Figure 1.2.7. Post-op maxillary intra-oral

Figure 1.2.8. Post-op mandibular intra-oral

M. Prognosis and Discussion

- This patient was on a typical therapeutic regime. Involvement of the respiratory system meant that she was on ventolin and flixotide inhalers as well as flucloxacillin as prophylaxis against chest infections. Damage to the pancreas had resulted in the requirement of pancreatin, a combination of pancreatic enzymes. In addition, supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins was required as well as a diet high in refined carbohydrate and protein, and a full fat content.

In general, children with cystic fibrosis have low levels of dental caries. It is, therefore, surprising that three cavities were present. A number of factors may have contributed to this. All three teeth had enamel defects and two had been restored with amalgam which had developed secondary caries. Diet analysis revealed a high consumption of sweet drinks between meals, a finding further supported by the degree of erosion present.

The fact that there was some erosion present could be also considered unusual. No studies have specifically examined erosion in children with cystic fibrosis; however, salivary studies have demonstrated higher concentration of salivary bicarbonate and phosphates with consequent increased pH (Kinirons 1985). It would seem that, in this case, the high frequency of acidic drinks negated this protection.

The aims of prevention were to halt further development of oral lesions and to maintain the positive attitude that the patient displayed to dentistry. Ultimately, general anesthesia (GA) was strongly contra-indicated given her respiratory status and it was therefore extremely important not to reach a stage when this was necessary.

The patient was vulnerable to chest infections and her mother was naturally keen to protect her when these developed. This resulted in a number of cancelled appointments, especially during the winter and autumn.

The overall response to treatment was very positive. Compliance both with treatment and preventive messages was excellent and the overall prognosis could be considered very good.

N. Common Complications and Alternative Treatment Plans

- Extensively decayed maxillary left second primary molar and mandibular left second primary molar

- Pulpectomy or extraction if teeth are non-vital with infection. If extracted, space maintenance must be addressed

Self-study Questions

1. Why do CF patients have a high rate of calculus?

2. What two main systems are affected in this condition?

3. Studies have shown that caries rates are low in this condition. What reasons have been given for this?

4. What precautions are required for treatment under general anesthesia in CF patients?

5. What are the long-term complications of CF?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography and Additional Reading

Aps JKM, Van Maele GOG, Martens LC. 2002. Caries experience and oral cleanliness in cystic fibrosis homozygotes and heterozygotes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 93:560–3.

Blomfield J, Warton KL, Brown JM. 1973. Flow rate and inorganic components of submandibular saliva in cystic fibrosis. Arch of Dis Child 48:267–74.

Davies JC, Alton EWFW, Bush A. 2007. Cystic fibrosis. BMJ 335:1255–9.

Haworth CS. 2010. Impact of cystic fibrosis on bone health. Curr Opin Pulm Med 616–22.

Kinirons MJ. 1985. Dental health of children with cystic fibrosis: An interim report. J Paediatr Dent 1:3–7.

Kinirons MJ. 1989. Dental health of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis in Northern Ireland. Community Dent Health 6:113–20.

Kinirons MJ. 1992. The effect of antibiotic therapy on the oral health of cystic fibrosis children. Internat J Paediatr Dent 2:139–43.

Mogayzel PJ Jr, Flume PA. 2011. Update in cystic fibrosis 2010. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183:1620–4.

Narang A, Maguire A, Nunn JH, Bush A. 2003. Oral health and related factors in cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory disorders. Arch Dis Child 88:702–7.

Turcios NL. 2005. Cystic fibrosis—an overview. J Clin Gastroenterol 39:307–17.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. They have altered amounts of calcium and phosphate in their saliva, which affect calculus formation. However, pancreatin may have a role in decreasing calculus formation and reducing dental caries in these patients

2. Respiratory and gastro-intestinal

3. This fact has been attributed to the long-term antibiotic therapy of these children, high salivary pH, and raised salivary calcium levels

4. The precautions for treatment under general anesthesia are:

- Avoid general anesthesia if possible

- Make sure that there are no signs of pulmonary infection. May require sputum culture

- Chest radiograph

- Blood gases

- Pulmonary function testing

- Vigorous course of pre-op and post-op chest physiotherapy to clear as much of the secretions as possible

- Check for diabetes (blood glucose) and liver disease (LFTs) pre-op

- Check current antibiotic regimen

- Peri-operative frequent suctioning and removal of secretions

- Nasal polyps are a contra-indication to nasal intubation

5. Long-term complications of CF include diabetes, liver disease, pneumothorax, sinusitis, nasal polyps, osteopenia, failure to thrive, and infertility

Case 3

Hemophilia A

Figure 1.3.1a–b. Facial photographs

A. Presenting Patient

- 4-year-, 2-month-old Hispanic male

- New patient referred by his physician

B. Chief Complaint

- Child states, “My tooth hurts when I eat candy”

- Mother states, “Has only been a problem for one week”

C. Social History

- Patient attends preschool

- Middle class family, married parents, mother is primary caregiver, patient is the only child

D. Medical History

- Severe Hemophilia A

- Two emergency room visits in the past year for injury-associated bleeding (knee and elbow)

- Medications: IV Advate® (recombinant factor VIII) three times a week administered at home by mother

- The patient has no food or drug allergies and his vaccinations are up-to-date

- Type and severity of hemophilia

- Hemophilia team contact information

- Compliance with medications

- Frequency and management of bleeding episodes

- Inhibitor status

- History of blood borne diseases such as HIV infection or hepatitis due to blood transfusions

- Limitations or restrictions on activities

E. Medical Consult

- Hemophilia Team

- Hemophilia occurs in 1 out of every 5,000 males. Hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency), the most common type (85% of the cases), and hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency) are X-linked recessive traits. Hemophilia C (factor XI deficiency) is an autosomal recessive trait most frequently presenting in Ashkenazi Jews

- Hemophilia presents as impaired secondary hemostasis (stabilization of the platelet plug with fibrin) while primary hemostasis (platelet plug formation) is normal. The disease is classified by level of factor activity (normal: 55% to 100%): severe(<1%), moderate (1% to 5%), and mild (>5%). The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is usually two to three times the upper limit of normal

- Patients with severe factor deficiencies may bleed spontaneously in muscles, skin, and joints, which may eventually develop arthropy, particularly in the ankles and knees. The incidence of joint pathology is decreased with prophylactic factor administration which is done multiple times a week in cases of moderate and severe hemophilia to increase factor levels to approximately 5%

- For breakthrough bleeds, additional factor replacement is needed together with administration of antifibrinolytic medications such as aminocaproic acid (AMICAR) or tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron). Desmopressin (DDAVP) increases plasma levels of factor VIII and may be useful in mild hemophilia A

F. Dental History

- No dental home

- Fair oral hygiene; no adult supervision

- Three meals and two snacks daily. Special snack of candy bar or soda is given as reward after each IV infusion

- Brushes with fluoridated toothpaste once a day

- Lives in optimally fluoridated area

- No history of trauma

G. Extra-oral Examination

- No significant findings

H. Intra-oral Examination

Soft Tissues

- Marginal gingivitis around molars

Hard Tissues

- No significant findings

Occlusal Evaluation of Primary Dentition

- No significant findings

Moderate Plaque Accumulation

Enamel Chipping on Incisal Edges of Mandibular Incisors

Intact Dentition on Visual Exam

I. Diagnostic Tools

- Two bitewing radiographs

- Maxillary and mandibular incisor occlusal radiographs

- Interproximal caries noted between molars

Figure 1.3.2a–d. Pre-op intra-oral radiographs. A. Right bitewing radiograph, B. Left bitewing radiograph, C. mandibular occlusal radiograph, D. Maxillary occlusal radiograph

J. Differential Diagnosis

- N/A

K. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Severe hemophilia A

- Early childhood caries

Problem List

- High risk of bleeding with invasive dental procedures and nerve blocks

- Untreated caries on the interproximal surfaces of all primary molars and incipient lesions in the maxillary left molars

- High caries risk due to special health care needs, lack of dental home, presence of caries, cariogenic diet, oral hygiene without adult supervision, and visible plaque and radiographic findings

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Establishment of a dental home and a caries prevention plan

- Prevention of head and oral trauma (helmets and mouth guard)

- Contact hemophilia team for factor management before and after dental care. Plan oral intubation for general anesthesia (GA) to minimize risk of airway trauma, and an aggressive treatment such as restoring all primary molars with stainless steel crowns

- Schedule a follow-up dental appointment in two weeks to check for complications and to reinforce prevention plan

- Three month recall

- Most patients can receive outpatient dental treatment. Appointments should be planned to minimize the need for factor infusions. Treatment under GA in a hospital should be considered for patients with extensive treatment needs and those with moderate or severe hemophilia. Always consult the hemophilia team before any dental work

- Prevention of dental problems is essential

- Avoid iatrogenic trauma to the oral />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses