1

Medical History, Physical Evaluation, and Risk Assessment

I. Background

The U.S. and global population demographics are constantly changing, chronic diseases are becoming more prevalent, new medications are being developed and brought to the market, and new and reemerging infectious diseases are being identified. These trends result in more patients seeking oral health care who have underlying medical conditions that may alter oral health status, treatment approaches, and outcomes. The challenges of medical history information gathering and risk assessment required for safe dental treatment planning and care delivery will be discussed and presented in a practical manner applicable to day-to-day needs of the general practice dentist. There are four key considerations that serve as a framework for assessing and managing the risks of dental care used in this book, although additional considerations may be relevant for certain medical conditions. The key considerations are hemostasis, susceptibility to infections, drug actions/interactions, and ability to tolerate the stress of dental care. The potential for the dental practice to encounter different types of medical emergencies is related to the patient’s medical health, adequacy of management, and stress tolerance.

- Hemostasis

- Susceptibility to infections

- Drug actions/interactions

- Patient’s ability to tolerate dental care

II. Medical History

A medical history can be recorded by the patient in advance of the dental appointment and reviewed by providers seeking clarification of patient responses. In the national shift to electronic health records, medical history, medications, and allergies may be recorded in a number of data collection formats and in a variety of settings, including use of web-based applications. Personal information should be kept private and shared only in compliance with privacy rules.

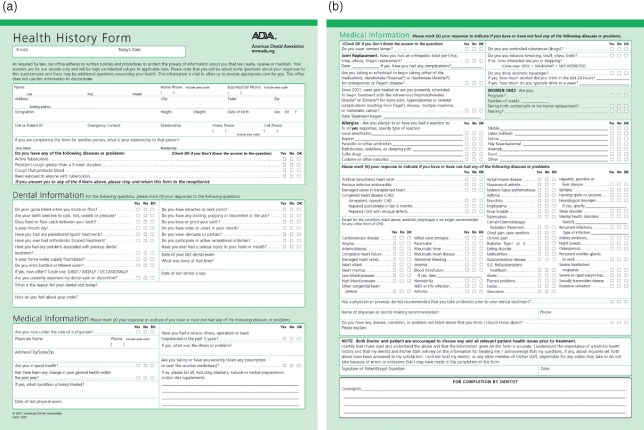

An example is the American Dental Association (ADA) Health History Form (see Fig. 1.1; available at http://www.ada.org), which is comprised of the following:

- demographic information;

- screening questions for active tuberculosis;

- dental information;

- medical information, including physician contact information;

- hospitalizations, illnesses, and surgeries;

- modified review of systems and diseases survey;

- medications (prescribed, over-the–counter and natural remedies, including oral and intravenous bisphosphonates);

- substance use history, including tobacco, alcohol, and controlled substances;

- allergies;

- a query about prosthetic joint replacements and any prior antibiotic recommendations by a physician or dentist and name and contact phone number of recommending provider;

- a query about the four cardiac disease conditions recommended for antibiotic coverage for prevention of infective endocarditis;

- a query of women about current pregnancy, nursing status, or birth control pills or hormonal therapy.

Figure 1.1 ADA Health History Forms. (a) Adult form S500 page 1, copyright 2007; (b) adult form S500 page 2, copyright 2007. Please see companion website (www.wiley.com/go/patton) for full-sized forms.

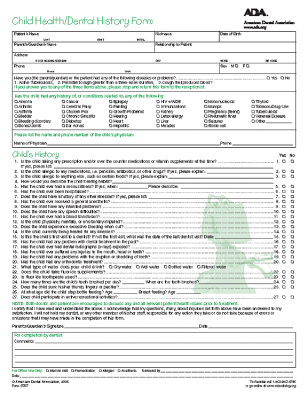

There is a Child Health/Dental History Form (see Fig. 1.2) also available from the ADA that focuses on inherited, developmental, infectious, and acquired diseases of importance to dental health-care delivery for children.

Figure 1.2 ADA Child Health/Dental History Form S707, copyright 2006.

Family history can facilitate awareness of need to screen for and engage in prevention efforts for common diseases such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and rarer diseases including hemophilia, sickle cell anemia, and cystic fibrosis. The Surgeon General has created a family health history initiative to facilitate family discussion of inherited diseases. This free tool found at https://familyhistory.hhs.gov will allow patients and providers to download the form to gather relevant health information for patients to share with providers. Whether disease etiology derives from genetics, environment, learned behaviors, or a combination of factors, many health conditions, such as propensity to hypertension, may run in families.

III. Physical Evaluation and Medical Risk Assessment

The initial and ongoing assessment of patient medical risk in dental practice has several purposes:

- To minimize risk of adverse events in the dental office resulting from dental treatment.

- To identify patients who need further medical assessment and management.

- To identify patients for whom specific perioperative therapies or treatment modifications will minimize risk, including postponing elective treatment.

- To identify appropriate anesthetic technique, intraprocedure monitoring, and postprocedure management.

- To discuss treatment procedures with patients, outlining risks and benefits, in order to obtain informed consent and determine need for additional anxiolysis.

One of the most common medical risk assessment frameworks is the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Score1 used to classify patients for anesthesia risk (Table 1.1). A medical risk-related health history is important to detect medical problems in patients. While across all ages most (78%) dental patients are healthy ASA 1 patients, the percentage that is of higher ASA physical status (ASA 2–ASA 6) increases with increasing age.2 By age 65, only 55% of adults remain healthy ASA 1. Medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension account for a high proportion of ASA 3 and ASA 4 patients.

Table 1.1. American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Physical Status Classification, Activity Characteristics/Treatment Risk, and Medical Examples

| ASA Physical Status | Activity Characteristics/Treatment Risk | Medical Examples |

| ASA 1 A normal healthy patient. |

|

|

| ASA 2 A patient with mild systemic disease. |

|

|

| ASA 3 A patient with severe systemic disease. |

|

|

| ASA 4 A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life. |

|

|

| ASA 5 A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation. |

|

|

| ASA 6 A declared brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes. |

|

|

Up to a third of dental patients who answer yes to “Are you in good health?” on verification are found to be medically compromised.3 In a survey of dental patients completing health history forms based on the ADA Health History Form available at the time, the diseases most inaccurately reported or omitted were blood disorders, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.3 The authors concluded that using both a self-administered questionnaire and dialog on the health history might improve communication.

There are several physical signs or clues that indicate a patient who reports having received no medical care might not truly be healthy, but rather simply not accessing medical care:

- age over 40 years,

- obese or cachectic body habitus,

- low energy level,

- abnormal skin coloration,

- poor oral hygiene,

- tobacco smoking.

Often the patient’s response to the question “Can you walk up two flights of stairs without stopping to catch your breath?” can indicate general cardiovascular and pulmonary health status.

Vital signs, including blood pressure and heart rate (pulse), should be assessed at each visit. The other vital signs of temperature, respiration rate, and pain score may be useful additional signs of current health. A focused review of systems should allow a cursory review of the patient’s recent state of health, focusing on recent changes and tailored to the patient and planned dental procedure(s).

- General: fever, chills, night sweats, weakness, fatigue

- Cardiovascular: reduced exercise tolerance, chest pain, orthopnea, ankle swelling, claudication

- Pulmonary: upper respiratory infection symptoms––productive cough, bronchitis, wheezing

- Hematological: bruising, epistaxis

- Neurological: mental status changes, transient ischemic attacks, numbness, paresis

- Endocrine: polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, weigh gain/loss

Under each medical topic, we present “key questions to ask the patient” to allow improved risk assessment and determination of dental treatment modifications.

Communication with the Patient’s Physician

The dentist should consult with the patient’s physician to clarify areas of the patient’s health that are unclearly communicated by the patient who is a poor historian or where a reported medical condition is monitored and the patient does not have complete information. This includes consultations about current laboratory assessments, prescribed medications and other medical and surgical therapies, and coordination of care. Under each medical topic, we present “key questions to ask the physician” to facilitate improved communication and coordination of care.

Influence of Systemic Disease on Oral Disease and Health

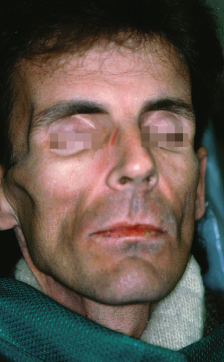

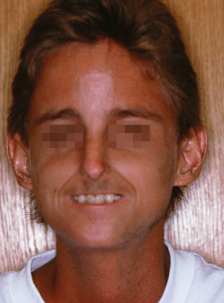

The health history should give the dentist an appreciation of oral conditions that may have a systemic origin and thus require systemic management as an aspect of treatment. Several abnormal signs and symptoms in the facial region, oral structures, and teeth with systemic origin are listed in Table 1.2 and illustrated in Figs. 1.3–1.6.

Table 1.2. Facial, Oral, and Dental Signs Possibly Related to Medical Disease or Therapy

| Possible Causative Medical Disease or Therapy | |

| Facial signs | |

| Cachexia | Wasting from cancer, malnutrition, HIV/AIDS |

| Cushingoid facies | Cushing syndrome, steroid use |

| Jaundiced skin/sclera | Liver cirrhosis |

| Malar rash | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Ptosis | Myasthenia gravis |

| Taught skin and microstomia | Scleroderma, facial burns |

| Telangiectasias | Liver cirrhosis |

| Weak facial musculature | Neurological disorder, facial nerve palsy, tardive dyskinesia, myasthenia gravis |

| Oral signs | |

| Bleeding, ecchymosis, petechiae | Thrombocytopenia, thrombocytopathy, hereditary coagulation disorder, liver cirrhosis, aplastic anemia, leukemia, vitamin deficiency, drug induced |

| Burning mouth/tongue | Anemia, vitamin deficiency, candida infection, salivary hypofunction, primary or secondary neuropathy |

| Dentoalveolar trauma | Interpersonal violence, accidental trauma, seizure disorder, gait/balance instability, alcoholism |

| Drooling | Neoplasm, neurologic–amyotropic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease cerebrovascular accident, cerebral palsy, medications (e.g., tranquilizers, anticonvulsants, anticholinesterases) |

| Dry mucosa | Drug-induced xerostomia, salivary hypofunction from Sjögren’s syndrome, diabetes, or head and neck cancer radiation therapy |

| Gingival overgrowth | Leukemia, drug induced (phenytoin, cyclosporine, calcium channel blockers) |

| Hard tissue enlargements | Neoplasm, acromegaly, Paget’s disease, hyperparathyroidism |

| Mucosal discoloration or hyperpigmentation | Addison’s disease, lead poisoning, liver disease, melanoma, drug induced (e.g., zidovudine, tetracycline, oral contraceptives, quinolones) |

| Mucosal erythema and ulceration | Cancer chemotherapy, uremic stomatitis, autoimmune disorders (systemic lupus, Bechet’s syndrome), vitamin deficiency, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, drug induced, self-injurious behavior |

| Mucosal pallor | Anemia, vitamin deficiency |

| Nondental source oral/jaw pain | Referred pain (e.g., cardiac, neurological, musculoskeletal) including myofascial and temporomandibular joints, drug induced (e.g., vincristine chemotherapy), primary neoplasms, cancer metastases, sickle cell crisis pain, primary or secondary neuropathies |

| Opportunistic infections | Immune suppression (from HIV, cancer chemotherapy, hematological malignancy, primary immune deficiency syndromes), poorly controlled diabetes, stress |

| Oral malodor | Renal failure, respiratory infections, gastrointestinal conditions |

| Osteonecrosis | Radiation to the jaw, use of bisphosphonates and other bone-modifying agents |

| Poor wound healing | Immune suppression (from HIV, cancer chemotherapy, primary immune deficiency syndromes), poorly controlled diabetes, malnutrition, vitamin deficiency |

| Soft tissue swellings | Neoplasms, amyloidosis, hemangioma, lymphangioma, acromegaly, interpersonal violence or accidental trauma |

| Trismus | Neoplasm, postradiation therapy, arthritis, posttraumatic mandible condyle fracture |

| Dental signs | |

| Early loss of teeth | Neoplasms, nutritional deficiency (e.g., hypophosphatemic vitamin-D-resistant rickets, scurvy), hypophosphatasia, histiocytosis X, Hand–Schüller–Christian disease, Papillon–Lefevre syndrome, acrodynia, juvenile-onset diabetes, immune suppression (e.g., cyclic neutropenia, chronic neutropenia), interpersonal violence or other traumatic injury, radiation therapy to the jaw, dentin dysplasia, Trisomy 21-Down syndrome, early-onset periodontitis |

| Rampant dental caries | Salivary hypofunction from disease (e.g., Sjögren’s syndrome), post radiation, or xerogenic medications; illegal drug use (e.g., methamphetamines); inability to cooperate with oral hygiene and diet instructions |

| Tooth discoloration | Genetic defects in enamel or dentin (e.g., amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfect), porphyria, hyperbilirubinemia, drug induced (e.g., tetracycline) |

| Tooth enamel erosion | Gastroesophageal reflux disease, bulimia nervosa |

Figure 1.3 Cachexia due to HIV wasting syndrome.

Figure 1.4 Cushingoid faces and malar rash due to systemic lupus erythematosus and chronic steroid use.

Figure 1.5 Taught facial skin and microstomia due to systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

Figure 1.6 Facial port-wine stain of Sturge–Weber syndrome (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis).

The astute dental provider also has the opportunity to observe physical and oral conditions that might indicate undiagnosed or poorly managed systemic disease. Example/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses