Chapter 1

Introduction

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of the meaning and interpretation of quality in the broadest sense and to highlight some of the key benefits of a commitment to quality.

Outcome

The reader will have an understanding of how the meaning of quality can vary in relation to its context and the relevance of the various interpretations in everyday dental practice.

Introduction

Healthcare quality has been on the agenda of scholars, policy analysts, providers and patients for many decades. By the 1970s, Avedis Donabedian had established his model for assessing quality on the basis of structure, process and outcome. A decade later, patient safety, risk management and appropriateness of care were added to the common list of measurement variables.

Many practice websites, leaflets and marketing materials make references to quality, but few are explicit about its meaning and interpretation.

“Quality … you know what it is, yet you don’t know what it is. But that’s self-contradictory. But some things are better than others, that is, they have more quality. But when you try to say what the quality is, apart from the things that have it, it all goes poof! There’s nothing to talk about …” So wrote Robert M. Pirsig in his book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (p.163). In his PhD thesis “On Quality of Dental Care”, Poorterman makes a similar point that: “A person generally is able to make an image of the meaning of that particular word and recognises it when in contact, but it is difficult to give the exclusive right description.”

The meaning of quality is explored further in Chapter 2.

In general dental practice, quality is the measure of how good dental health outcomes are, and can be evaluated for at least two components. The technical element of quality care looks at the components of clinically appropriate diagnostic decision-making, treatment planning and execution and any required follow-up.

The personal element includes the degree to which the patient perceives being cared for – confidence, compassion, trust – and an overall sense of satisfaction from the practice as a whole. While the technical element of quality is relatively objective, and the personal relatively subjective, both are measurable.

Writing in the British Dental Journal in 1996, Mindak points out that: “Patients judge the dental service they receive by the interaction with the service providers – the dentist and his or her staff – as they are unable to judge the technical quality of the service.”

The interactive and organisational elements make us unique; we may know the recipe for quality in general practice but the way we choose to apply it results in a blend that is unique to each and every practice.

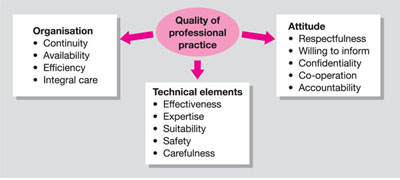

The Dutch National Council for Public Health has developed a framework that describes quality in clinical practice (Fig 1-1).

Fig 1-1 The Dutch National Council for Public Health framework for quality in clinical practice.

A quality clinical outcome will result from a combination of the aspects under each of the three domains, some of which will be more important than others for each patient experience (Fig 1-2).

Fig 1-2 Quality outcome (a–e) Teeth suitable for direct build-up with resin composite featuring caries and tooth wear. (b) Unaesthetic anterior view due to tooth wear, resulting in translucent incisal edges. (c) Split rubber-dam isolation. (d) Completed treatment (anterior view). (e) Completed treatment (palatal view).

Challenges

We live in the age of the mixed economy and there are challenges in managing quality in this context. Many practices choose to provide care and services through private and public sector funding. These practices must satisfy the meaning of quality as defined by the stakeholders of all the parties. Who is the customer in the public sector – the commissioner or the patient? Is there shared status? Equity is the priority in many public sector services. The requirement to maintain a/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses