1

General Principles Related to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Impacted Teeth

Dental age

Assessing dental age

When is a tooth considered to be impacted?

Impacted teeth and local space loss

Whose problem?

The timing of the surgical intervention

Patient motivation and the orthodontic option

In order for us to understand what an impacted tooth is and whether and when it should be treated, it is necessary first to define our perception of normal development of the dentition as a whole and the time-frame within which it operates.

Dental Age

A patient’s growth and development may be faster or slower than average and we may assess his age in line with this development [1]. Thus, a child may be tall for his age, so that his morphological age may be considered to be advanced. By studying radiographs of the progress of ossification of the epiphyseal cartilages of the bones in the hands of a young patient (the carpal index) and comparing this with average data values for children of his age, we are in a position to assess the child’s skeletal age. Similarly, there is a sexual age assessment related to the appearance of primary and secondary sexual features, a mental age assessment (intelligence quotient, or IQ, tests), an assessment for behaviour and another to measure the child’s self-concept. These indices are used to complement the chronological age, which is calculated directly from the child’s birth date, to give further information regarding a particular child’s growth and development.

Dental age is another of these parameters, and it is a particularly relevant and important assessment, used in advising proper orthodontic treatment timing. Schour and Massler [2], Moorrees et al. [3, 4], Nolla [5], Demerjian et al. [6] and Koyoumdjisky-Kaye et al. [7] have drawn up tables and diagrammatic charts of stages of development of the teeth, from initiation of the calcification process through to the completion of the root apex of each of the teeth, together with the average chronological ages at which each stage occurs.

Eruption of each of the various groups of teeth is expected at a particular time, but this may be influenced by local factors, which may cause premature or delayed eruption with a wide time-span discrepancy. For this reason, eruption time is an unreliable method of assessing dental age.

With few exceptions, mainly related to frank pathology, root development proceeds in a fairly constant manner usually regardless of tooth eruption or the fate of the deciduous predecessor. It therefore follows that the use of tooth development as the basis for dental age assessment, as determined by an examination of periapical or panoramic X-rays, is a far more accurate tool.

Thus, we may find that a child of 11–12 years of age has four erupted first permanent molars and all the permanent incisors only, with deciduous canines and molars completing the erupted dentition. If the practitioner were merely to run to the eruption chart, he would note that at this age all the permanent canines and premolars should have erupted, and he would conclude that the 12 deciduous teeth have been retained beyond their due time. The treatment that would then appear to be the logical follow-up of this observation requires the extraction of these 12 deciduous teeth! However, there are two possibilities in this situation and, in order to prevent unnecessary harm being inflicted on the child and his parents, the radiographs must be carefully studied to distinguish one context from the other.

In the event that the radiographs show the unerupted permanent canines and premolars having completed most of their expected root length, then the child’s dental age corresponds with his chronological age (Figure 1.1). The deciduous teeth have not shed naturally, due to insufficient resorption of their roots. As such, we have to presume that they are the impediment to the normal eruption of the permanent teeth. Their permanent successors may then strictly be defined as having delayed eruption. Under these circumstances it would be logical to extract the deciduous teeth on the grounds that their continued presence defines them as over-retained.

Fig. 1.1 Advanced root development of the canines and premolars in a 10-year-old child defines these teeth as exhibiting delayed eruption. The overall dental age is 12–13 years, with very late developing second permanent molars, particularly on the mandibular right side.

The second possibility is that the radiographs reveal relatively little root development, more closely corresponding, perhaps, to the picture of the 9-year-old child on the tooth development chart (Figure 1.2). The child’s birth certificate may indicate that he is 12 years of age, and this may well be supported by his body size and development, and by his intelligence. Nevertheless, his dentition is that of a child three years younger, determining his dental age as 9 years and diagnosing a late-developing dentition. Extraction in these circumstances would be the wrong line of treatment, since it is to be expected that these teeth will shed normally at the appropriate dental age and early extraction may lead to the undesired sequelae characteristic of early extraction, performed for any other reason.

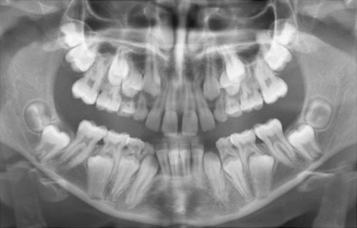

Fig. 1.2 A 12-year-old patient with root development defining dental age as 9 years. Extraction of deciduous teeth is contraindicated.

From this discussion, we are now in a position to define the terms that we shall use throughout this text. The first refers to a retained deciduous tooth, which has a positive connotation and which may be defined as a tooth that remains in place beyond its normal, chronological shedding time due to the absence or retarded development of the permanent successor. By contrast and with a negative connotation, an over-retained deciduous tooth is one whose unerupted permanent successor exhibits a root development in excess of three-quarters of its expected final length (Figure 1.3). Thus, a radiograph of the permanent successor is needed to determine the status of the deciduous tooth and, by implication, its treatment.

Fig. 1.3 The mandibular left second deciduous molar is retained (extraction contraindicated), since the root development of its successor is inadequate for normal eruption. The right maxillary deciduous canine, in contrast, is over-retained (extraction advised), since the long root of its successor illustrates delayed eruption.

A permanent tooth with delayed eruption is an unerupted tooth whose root is developed in excess of this length and whose spontaneous eruption may be expected in time. A tooth which is not expected to erupt in a reasonable time in these circumstances is termed an impacted tooth.

Dental age is not assessed with reference to a single tooth only, since some variation is found within the different groups of teeth. An all-round assessment must be made and, only then, can a definitive determination be offered. However, in doing this one should be wary of including the maxillary lateral incisors, the mandibular second premolars and the third molars, the timing of whose development is not always in line with that of the remaining teeth [8, 9]. These are the same teeth that are most frequently congenitally missing in cases of partial anodontia (oligodontia). Indeed, reduced size, poorly contoured crown form and late development of these teeth are all considered microforms of missing teeth [9–11]. It is important to note that this variation in the timing of their development is only ever expressed in lateness, and they are not to be found in a more advanced state of development than the other teeth. If the individual dental ages of any of these variable groups of teeth is advanced, then so too is the entire dentition in which they occur.

Assessing Dental Age

When studying full-mouth periapical radiographs or a panoramic film several criteria can be used in the estimation of tooth development. The first radiographic signs of the presence of a tooth are seen shortly after the initiation of calcification of the cusp tips. Thereafter, one may attempt to delineate the completed crown formation and various degrees of root formation (usually expressed in fractions), through to the fully closed root apex. By and large, orthodontic treatment is performed on a relatively older section of the child population and, as such, the stages of root formation are usually the only factors which remain relevant.

The stage of tooth development that is easiest to define is that relating to the closure of the root apex. For as long as the dental papilla is discernible at the root end, the apex is open and still developing. Once fully closed, the papilla disappears and a continuous lamina dura is seen to intimately follow the root outline. The accuracy with which one may assess fractions of an unmeasurable and merely ‘expected’ final root length is far less reliable and much more subject to individual observer variation.

Root development of the permanent teeth is completed approximately 2.5–3 years after normal eruption [5]. This allows us to conclude that, at the age of 9 years, the mandibular incisors (which erupt at age 6) will be the first teeth to exhibit closed apices and that these will usually be closely followed by the four first permanent molars. At 9.5 years, the mandibular lateral incisors will complete, while at 10 years and 11 years, respectively, the roots of the maxillary central and normally developing lateral incisors will be fully formed. This being so, when presented with a set of radiographs, we may proceed to assess dental age by following a simple line of investigation, which uses the dental age of 9 years as its starting point and then progresses forward or traces its steps back, depending on its findings.

If the mandibular central incisor roots are complete, we may presume the patient is at least 9 years old (dental age) and we may then advance, checking for closed apices of first molars (9–9.5 years), mandibular lateral incisors (9.5 years), maxillary central incisors (10 years), normally developing maxillary lateral incisors (11 years), mandibular canines and first premolars (12–13 years), maxillary first premolars (13–14 years), normally developing second premolars and maxillary canines (14–15 years) and second molars (15 years).

By this method, we may arrive at a tentative determination for dental age on the basis of the last tooth in this sequence which has a closed apex (Figure 1.4). It is now important to relate the actual development of the remaining teeth in the sequence to their expected development that may be derived from the wall chart or from tables that have been presented in the literature. This may then provide corroborative evidence in support of an overall and definitive dental age determination.

Fig. 1.4 Root apices are closed in all first molars, all mandibular and three of the maxillary incisors, excluding the left lateral incisor.

When the dental age is less than 9 years, none of the permanent teeth will have completed their root development and the clinician will have no choice but to rely on an estimation of the degree of root development, degree of crown completion and, in the very young, initiation of crown calcification (Figure 1.5). This is most conveniently done by working backwards from the expected development at age 9 years and comparing the dental development status of the patient to this, beginning with the mandibular central incisors and the first permanent molars. Thus, at dental age 6 years, one would find one-half to two-thirds root length of these teeth and this could be confirmed by studying the development of the other teeth. At the same time, one should expect unerupted maxillary central incisors with half root length, mandibular canines with one-third root length, first premolars with one-quart/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses