Chapter 1

An overview of the management of medical emergencies and resuscitation in the dental practice

INTRODUCTION

Every dental practice has a duty of care to ensure that an effective and safe service is provided for its patients (Jevon, 2012). The satisfactory performance in a medical emergency or in a resuscitation attempt in the dental practice has wide-ranging implications in terms of resuscitation equipment, resuscitation training, standards of care, clinical governance, risk management and clinical audit (Jevon, 2009).

The Resuscitation Council (UK) (2013) has updated its standards for clinical practice and training in resuscitation for dental practitioners and dental care professionals in general dental practice. All members of the dental team need to be aware of what their role would be in the event of a medical emergency and should be trained appropriately with regular practice sessions (Greenwood, 2009).

The aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of the management of medical emergencies and resuscitation in the dental practice.

CONCEPT OF THE CHAIN OF SURVIVAL

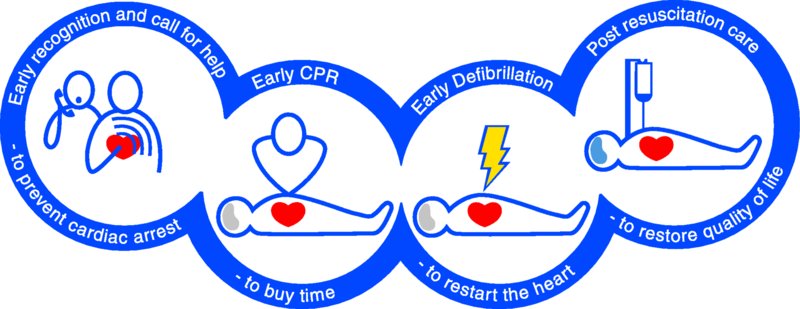

Survival from cardiac arrest relies on a sequence of time-sensitive interventions (Nolan et al., 2010). The concept of the original chain of survival emphasised that each time-sensitive intervention must be optimised in order to maximise the chance of survival: a chain is only as strong as its weakest link (Cummins et al., 1991).

The chain of survival (Figure 1.1) stresses the importance of recognising critical illness and/or angina and preventing cardiac arrest (both in and out of hospital) and post-resuscitation care (Nolan et al., 2006):

- Early recognition and call for help to prevent cardiac arrest: this link stresses the importance of recognising patients at risk of cardiac arrest, dialling 999 for the emergency services and providing effective treatment to hopefully prevent cardiac arrest (Nolan et al., 2010); patients sustaining an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest usually display warning symptoms for a significant duration before the event (Müller et al., 2006).

- Early CPR to buy time and early defibrillation to restart the heart: the two central links in the chain stress the importance of linking CPR and defibrillation as essential components of early resuscitation in an attempt to restore life. Early CPR can double or even triple the chances of a patient surviving an out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation (shockable rhythm) induced cardiac arrest (Holmberg et al., 1998, 2001; Waalewijn et al., 2001).

- Post-resuscitation care to restore quality of life: the priority is to preserve cerebral and myocardial function and to restore quality of life (Nolan et al., 2010).

Figure 1.1 Chain of survival. Source: Laerdal Medical Ltd, Orpington, Kent, UK. Reproduced with permission.

INCIDENCE OF MEDICAL EMERGENCIES IN DENTAL PRACTICE

The incidence of medical emergencies in dental practice is very low. Medical emergencies occur in hospital dental practice more frequently, but in similar proportions to that found in general dental practice (Atherton et al., 2000). With the elderly population in dental practices increasing, medical emergencies in the dental practice will undoubtedly occur (Dym, 2008).

A literature search for published surveys on the incidence of medical emergencies and resuscitation in the dental practice found the following.

Survey of dental practitioners in Australia

A postal questionnaire survey of 1250 general dental practitioners undertaken in Australia (Chapman, 1997) found that:

- one in seven (14%) had had to resuscitate a patient;

- the most common medical emergencies encountered were adverse reactions to local anaesthetics, grand mal seizures, angina and hypoglycaemia.

Survey of dentists in England

A survey of dentists (Girdler and Smith, 1999) (300 responded) in England found that over a 12-month period they had encountered:

- vasovagal syncope (63%) – 596 patients affected;

- angina (12%) – 53 patients affected;

- hypoglycaemia (10%) – 54 patients affected;

- epileptic fit (10%) – 42 patients affected;

- choking (5%) – 27 patients affected;

- asthma (5%) – 20 patients affected;

- cardiac arrest (0.3%) – 1 patient affected.

Survey of dental practitioners in a UK university dental hospital

Atherton et al. (2000) assessed the frequency of medical emergencies by undertaking a survey of clinical staff (dentists, hygienists, nurses and radiographers) at a university dental hospital. The researchers found that:

- fainting was the commonest event;

- other medical emergency events were experienced with an average frequency of 1.8 events per year;

- highest frequency of emergencies were reported by staff in oral surgery.

Survey of dentists in New Zealand

A total of 199 dentists responded to a postal survey undertaken by Broadbent and Thomson (2001) in New Zealand, with the following findings:

- Medical emergencies had occurred in 129 practices (65.2%) within the previous 10 years (mean – 2.0 events per 10,000 patients treated under local analgesia, other forms of pain control or sedation);

- Vasovagal events were the most common emergencies occurring in 121 (61.1%) practices within the previous year (mean 6.9 events per 10,000 patients treated under local analgesia, other forms of pain control or sedation).

Survey of dental staff in Ohio

A survey of dental staff in Ohio (Kandray et al., 2007) found that 5% had performed CPR on a patient in their dental surgery.

Survey of dentists in Germany

A survey of 620 dentists in Germany (Müller et al., 2008) found that in a 12-month period:

- 57% had encountered up to 3 emergencies;

- 36% had encountered up to 10 emergencies;

- Vasovagal episode was the most common reported emergency – average 2 per dentist;

- 42 dentists (7%) had encountered an epileptic fit;

- 24 dentists (4%) had encountered an asthma attack;

- 5 dentists (0.8%) had encountered choking;

- 7 dentists (1.1%) had encountered anaphylaxis;

- 2 dentists (0.3%) had encountered a cardiopulmonary arrest.

GENERAL DENTAL COUNCIL GUIDELINES ON MEDICAL EMERGENCIES

Standards for the Dental team (General Dental Council, 2013) emphasises that all dental professionals are responsible for putting patients’ interests first, and acting to protect them. Central to this responsibility is the need for dental professionals to ensure that they are able to deal with medical emergencies that may arise in their practice. Such emergencies are, fortunately, a rare occurrence, but it is important to recognise that a medical emergency could happen at any time and that all members of the dental team need to know their role in the event of one occurring.

The General Dental Council, in its publication Principles of Dental Team Working (General Dental Council, 2006), states that the person who employs, manages or leads a team in a dental practice should ensure that:

- There are arrangements for at least two people available to deal with medical emergencies when treatment is planned to take place;

- All members of staff, not just the registered team members, know their role if a patient collapses or there is another kind of medical emergency;

- All members of staff who might be involved in dealing with a medical emergency are trained and prepared to deal with such an emergency at any time;

- Members of the team practice together regularly in a simulated emergency so they know exactly what to do.

Maintaining the knowledge and competence to deal with medical emergencies is an important aspect of all dental professionals continuing professional development (General Dental Council, 2006). The above guidance has been endorsed by the Resuscitation Council (UK) (2013).

RESUSCITATION COUNCIL (UK) QUALITY STANDARDS

The Resuscitation Council (UK)’s Quality standards for cardiopulmonary resuscitation practice and training: primary dental care (2013) provides guidance and recommendations concerning the management of a cardiac arrest in the dental practice.

Topics covered include medical risk assessment, resuscitation procedures and the use of resuscitation equipment in the dental practice in general dental practice. It also includes topics such as staff training, patient transfer and post-resuscitation/emergency care.

The key recommendations in the statement are that:

- Every dental practice should have a procedure in place for medical risk assessment of their patients;

- Specific resuscitation equipment should be immediately available in every dental practice (this should be standardised throughout the United Kingdom);

- Every clinical area should have immediate access to an automated external defibrillator (AED);

- Dental practitioners and dental care professionals should receive training in CPR, including basic/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses