Diagnosis and treatment planning

What was the diagnosis?

The diagnosis was chronic periapical periodontitis associated with an infected necrotic root canal. The cause of pulp necrosis was very likely coronal leakage and caries exposure, although the possibility that the pulp may have been iatrogenically exposed during caries excavation should be considered. The exposed pulp may have been vital (although irreversibly inflamed) or already necrotic at the time of the previous course of restorative treatment. If the pulp was still vital at that time, caries associated with a leaking restoration may have maintained the insult to the pulp tissue, resulting in pulp necrosis.

What treatment should be carried out in this case?

Endodontic treatment should be performed, followed by placement of a well-adapted plastic composite restoration. The defective and discoloured restorations in the other maxillary incisors should also be replaced.

What are the goals of antimicrobial endodontic treatment?

The ultimate goal of the endodontic treatment is to maintain or restore health of the periapical tissues. The treatment of teeth with irreversibly inflamed pulps is essentially a prophylactic approach, since the radicular vital pulp is usually free of infection, and so the rationale is to treat the root canal to prevent further pulp necrosis and infection which would eventually result in periapical periodontitis. On the other hand, in cases of infected necrotic pulps like the case described here, an intraradicular infection is already established and, as a consequence, endodontic treatment should focus not only on prevention of introduction of new microorganisms, but also on elimination of those colonizing the root canal.

Entrenched in the protected anatomy of the root canal system, bacteria are beyond the reach of the host defences and systemically administered antibiotics. Therefore, endodontic infections can only be treated by means of endodontic treatment using antibacterial procedures.

Treatment procedures should ideally render the root canal system free of microorganisms. However, given the complex anatomy of the root canal system, it is widely recognized that, with available instruments, irrigants and preparation techniques, fulfilling this goal is virtually impossible for the vast majority of cases. Therefore, the realistic goal is to reduce bacterial populations to a level below that necessary to induce or sustain periapical disease. The clinician should adopt an evidence-based antibacterial protocol that predictably disinfects the root canal and allows this goal to be accomplished.

Discussion

How does caries cause pulp necrosis and subsequent periapical periodontitis?

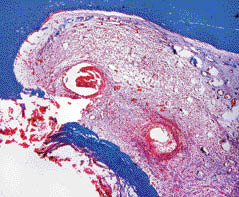

Bacteria within carious lesions are organized in authentic biofilms; if left untreated, this carious front advances towards the pulp and simultaneously the tooth structure is destroyed in the process. Diffusion of bacterial products through dentinal tubules induces pulp inflammation long before the pulp is exposed. After exposure, the pulp surface becomes colonized and covered by bacteria from the caries biofilm and becomes severely inflamed (Figure 1.1.2). Some tissue invasion by bacteria may also occur. As a response to the sustained bacterial challenge, the pulp tissue invariably undergoes necrosis and then loses the ability to contain the bacterial invasion. Eventually, invading bacteria colonize the necrotic pulp tissue. If left untreated, the events of bacterial aggression, pulp inflammation, necrosis and subsequent infection gradually move towards the apical portion of the root canal until virtually the entire root canal is necrotic and infected.

Figure 1.1.2 Histologic section of a tooth with caries exposure. The pulp was vital, but severely inflamed at the area of exposure (Gomori’s trichrome staining).

Bacteria colonizing the necrotic root canal will then induce damage to the periapical tissues and give rise to inflammatory changes. Bacteria exert their pathogenicity by wreaking havoc on the host tissues through direct and/or indirect mechanisms. Bacterial virulence factors that cause direct tissue harm include those that are toxic to host cells and/or disrupt the intercellular matrix of the connective tissue. Furthermore, bacterial structural components stimulate the development of host immune reactions capable not only of defending the host against infection, but also of causing severe tissue destruction. Pus formation in acute apical abscess and bone resorption associated with chronic periapical periodontitis are clear examples of tissue destructive effects indirectly caused by bacteria. They are indirect because of being promoted by the host itself in defence against bacterial infection.

In addition to caries lesions, are there other avenues for endodontic infection?

Under normal conditions, the pulp–dentine complex is isolated and protected from the oral microbiota by the overlying enamel and cementum, the same way the connective tissues elsewhere in the body are segregated from the microbiota residing in body cavities and surfaces by the epithelium of mucosa or skin. Once the integrity of these natural layers is breached (for example; as a result of caries, trauma-induced fractures and cracks, restorative procedures, scaling and root planning, attrition or abrasion) or naturally absent (for example; because of gaps in the cemental coating at the cervical root surface), the pulp–dentine complex will be exposed to the oral environment. This complex is then challenged by microorganisms present in carious lesions, saliva bathing the exposed dentinal area or in the dental biofilm formed onto the exposed area. The subgingival biofilm associated with periodontal pockets may also represent a source of microorganisms which may access the pulp via dentinal tubules at the cervical region of the tooth or through lateral and apical foramina.

Whatever the route of bacterial access to the root canal, necrosis of pulp tissue is a prerequisite for the establishment of primary endodontic infections. As long as the pulp is vital, it can protect itself against bacterial invasion and colonization. However, if the pulp becomes necrotic as a result of caries, trauma, operative procedures or periodontal disease, the necrotic tissue can be very easily infected. This is because host defences do not function in the necrotic pulp tissue.

What is the difference between a primary and secondary infection?

Primary (endodontic) infections occur in untreated teeth. Microorganisms may also be detected in root canals after

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses