The Parotid and Submandibular Papillae

Patient Selection for Sialendoscopy

Physical Examination: Inspection and Palpation

Local Anesthesia of the Parotid Gland

Local Anesthesia of the Submandibular Gland

Local Anesthesia with Sedation

Probes, Dilators, Guide Wires, Bougies

Retropapillary Approach to the Duct

Scope Sterilization: Autoclave, Gas, Soaking

Introduction

Sialendoscopy is a recently developed semirigid optical technique that is used to inspect and manipulate pathological conditions located in the salivary gland ductal system. Because of the limited size of the ductal system, the development of the instruments used has required unique engineering expertise. Sialendoscopy, first described in 1990,1 is widely performed for major salivary gland “lithiasis-like” or obstructive syndromes to aid in making a diagnosis and to carry out treatments. This chapter deals with the diagnostic aspects of sialendoscopy.

Definition

Diagnostic sialendoscopy is defined as a method of inspecting the major salivary gland ductal system by inserting a small-caliber endoscope. The procedure aids in the diagnosis of lithiasis (salivary stones), ductal stenosis, and other types of pathological condition that can be visualized in the ducts.

Interventional sialendoscopy can be defined as a method of manipulating pathological conditions identified on diagnostic sialoendoscopy—e.g., by removing stones, dilating structures or stenoses with balloons or stents, and taking biopsies of abnormal ductal lesions. Instruments are needed to perform these manipulations and have to be inserted through the working channel alongside the endoscope’s inspection channel.

Sialendoscopic Anatomy

The Ductal System

The Ductal System

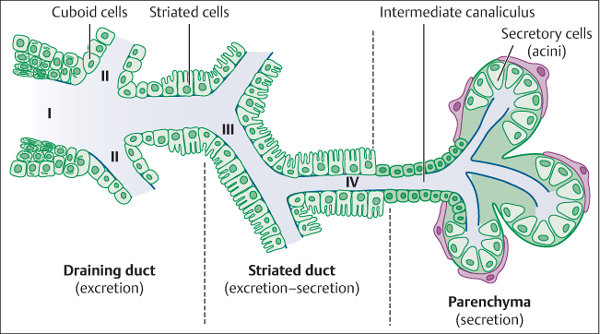

The ductal system originates in the major salivary glands and terminates at the salivary papilla. Running from the papilla to the gland is the main duct or primary duct (known as the Wharton duct in the case of the submandibular gland and as the Stensen duct in the parotid gland), which separates into secondary levels or branches without systematization, with decreasing ductal diameters from the main duct to the terminal glandular substance. It is not possible to enter the third-level or fourth-level branches, and the ability to explore each ductal level depends on the diameter and orientation in each. The usable diameter is less than 3–4 mm in the submandibular gland primary duct and less than 2 mm in the parotid gland primary duct.2 The main duct is lined with salivary cuboid cells. The second-level and third-level branches are lined with striated cells, which have a secretory role. The terminal glandular branches are only lined with secretory cells, with an acinar architecture (Fig. 9.1).

Fig. 9.1 The ductal system of a major salivary gland. Moving from left to right (as seen on sialendoscopy from the papilla to the glandular substance), the scope follows: I, the main duct; II, second-level branches; III, third-level branches; and IV, fourth-level branches.

The Parotid and Submandibular Papillae

The Parotid and Submandibular Papillae

The parotid and submandibular papillae are distinctly different, and different and specific surgical techniques are required in order to enter or penetrate each.

The parotid papilla is located on the buccal mucosa bilaterally, at the level of the second upper molar. When the scope has entered the papilla, the duct is followed perpendicularly through the mucosa and then posteriorly toward the buccinator muscle. The duct then turns around the anterior border of the masseter muscle to reach the substance of the parotid gland.

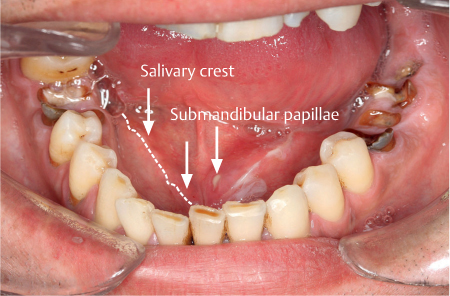

The submandibular papillae are located on either side of the frenulum of the tongue on the anterior floor of the mouth. They are pediculated at the medial part of the salivary crest; the duct orifice is located on the upper papilla surface (Fig. 9.2). The submandibular papilla is difficult to enter or cannulate due to its lack of rigidity, with a freely mobile, “wobbly” duct opening. The technique of submucosal infiltration around the papilla is very helpful for stabilizing or fixing the papilla.3 It is sometimes not possible to cannulate the submandibular papilla, however, and another approach known as the retrograde papilla method has been therefore been developed (see below).

Fig. 9.2 The papillae of the Wharton ducts (submandibular glands). On the left is the salivary crest, dividing the sublingual slope from the lingual slope. The papillae are situated at the end of the lingual slope of the salivary crest (arrows). The left papilla is open, showing pus.

Patient Selection for Sialendoscopy

The indications for interventional sialendoscopy are presented in Chapter 15. As sialendoscopy is a relatively new clinical technique, new indications are regularly being described and published, and the list of indications is therefore not yet finalized. Currently, the main indications for sialendoscopy are in patients with the obstructive mealtime syndrome, most often due to lithiasis (stones), especially in the submandibular glands, and less frequently due to ductal stenosis.

In a series of 200 sialendoscopy cases, it was observed that:

Ninety percent of obstructive submandibular syndromes were due to lithiasis and 10% to stenosis or allergic sialadenitis.

Ninety percent of obstructive submandibular syndromes were due to lithiasis and 10% to stenosis or allergic sialadenitis.

Fifty percent of obstructive parotid syndromes were due to lithiasis, while the other 50% were due to ductal stenosis, which is observed as frequently as lithiasis in parotid gland mealtime syndrome.4

Fifty percent of obstructive parotid syndromes were due to lithiasis, while the other 50% were due to ductal stenosis, which is observed as frequently as lithiasis in parotid gland mealtime syndrome.4

In patients who suffer salivary gland swelling or enlargement at mealtimes, other causes have also been observed, such as ductal kinks, mucous plugs, ductal polyps, and foreign bodies. In some cases, no cause is found and a diagnosis of obstructive allergic sialadenitis is considered.

The informed consent procedure is discussed in Chapter 15. As in all surgical techniques, patients need to be warned that sialendoscopy can result in morbidity, even though it is a relatively atraumatic procedure. Sialendoscopy can be combined with other surgical interventions, such as a combined technique (endoscopy together with an open ductal exploration) and/or excision of the main gland substance. The risks of the procedure have to be explained to each patient, as well as the possibility of carrying out different combinations of procedures in a single surgical session, or alternatively in different sessions. However, doing all of the relevant procedures in a single sitting or a single surgical session is regarded as best practice.

Because of the different shapes of the papillae, it is easier to penetrate the Stensen duct than the Wharton duct. However, the Wharton duct is easier to explore than the Stensen duct because of the ductal anatomy and diameter.

Because of the different shapes of the papillae, it is easier to penetrate the Stensen duct than the Wharton duct. However, the Wharton duct is easier to explore than the Stensen duct because of the ductal anatomy and diameter.

Clinical Features

Mealtime Syndrome

Mealtime Syndrome

The mealtime syndrome is classically associated with cheek pain and salivary gland swelling. The majority of patients scheduled for sialendoscopy suffer from a possible mechanical salivary ductal obstruction, which induces pain and swelling in the major salivary glands. These symptoms—pain and gland swelling—are classically encountered at the start of the period of episodic obstruction, but after a few weeks or months, the syndrome changes more to that of continuous cheek pain and swelling. Without treatment, some of the infectious episodes can precipitate increased pain, local gland inflammation with pus appearing at the papilla, and associated fever.

Systematic Radiography

Systematic Radiography

In some cases, the typical symptoms of the mealtime syndrome are not present. In these patients, the diagnosis is made or confirmed on a radiographic panoramic view or an occlusal view of the floor of the mouth, usually requested for dental reasons, or on computed tomography (CT) of the neck or mouth, or using ultrasound of the neck and salivary glands.

Signs of Infection

Signs of Infection

Infection may present as ductal, glandular, or periductal swelling with pain. The infectious complications of ductal obstruction are sometimes the only symptoms and signs that prompt the patient to seek medical advice.

Diagnostic Work-Up

Physical Examination: Inspection and Palpation

Physical Examination: Inspection and Palpation

The physician must be seated in front of the patient, on the same level. Tongue depressors or retractors, gloves, and good illumination of the mouth are essential equipment for a thorough examination of the oral cavity.

The first step is an extraoral examination, in an attempt to locate the gland swelling (unilateral or bilateral); there may or may not be tenderness, loss of gland elasticity, redness of the overlying skin (erythema), or a discharging sinus or fistula.

The second step is an intraoral examination, starting with an inspection of the papilla to see whether there is any saliva or even pus being produced, and observation of the local mucosa around the papilla area to assess any redness (erythema) or swelling of the anterior floor of the mouth.

The third step involves a combination of intraoral and extraoral palpation of the floor of the mouth and/or cheek, both anteriorly and laterally, to detect any thickening or the presence of a foreign body such as a stone. The location of a stone on bimanual palpation makes it possible to select the best treatment for duct obstruction5 (Fig. 9.3).

Fig. 9.3 Bimanual palpation of the floor of the mouth. Palpation should be carried out by moving from the gland to the papilla. When the palpation is finished, the clinician should inspect the papilla to assess the flow of pus or saliva (cf. Fig. 9.2).

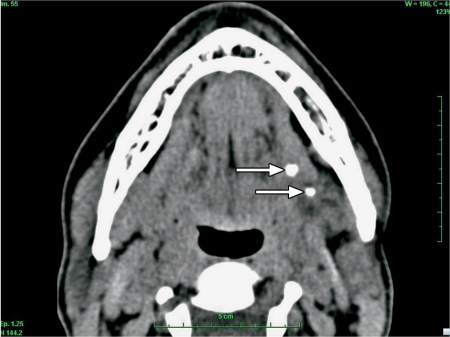

Fig. 9.4 Computed tomography without contrast injection to evaluate an obstructive mealtime syndrome in the left submandibular gland. Two stones are visible (arrows). Only one stone had been visualized on ultrasound.

Imaging before Sialendoscopy

Imaging before Sialendoscopy

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is an inexpensive, atraumatic, noninterventional technique that is often used to investigate pathological conditions in the salivary glands. If a specialist ultrasonographer is available, the accuracy of examinations for salivary gland diseases is reported to be over 90%, but the accuracy falls to below 50% when an ultrasonographer who is not a salivary gland specialist is used.6 When it is performed by a specialist ultrasonographer or sialendoscopist, ultrasound may be the only investigation that is indicated before endoscopy is carried out, and it is reported that the location and diameter of stones and ductal enlargement are easily evaluated with ultrasound alone.

Sialography

This examination technique also requires an experienced radiologist, and it exposes the patient to radiation. Sialography still has a role in the investigation of salivary gland obstruction. The mobility of stones can be assessed during sialography, and this is an important characteristic when choosing the best extraction technique. In stenoses, sialography provides better definition than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and it can also estimate the length and diameter of the stenosis better than diagnostic sialendoscopy.

Computed Tomography

CT scan without injection (Fig. 9.4) is more expensive than ultrasound and exposes patients to radiation, but CT is nevertheless still the most sensitive imaging technique for diagnosing salivary stones. Routine use of iodine injection is not recommended, as it may lead to diagnostic errors in differentiating between injected blood vessels and stones. CT has an overall accuracy of 90%, irrespective of the clinical expertise available, and for physicians it is a better way of locating stones than ultrasound.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI does not expose patients to radiation. Depending on the sequence used, MRI shows stones as black against the background of the duct and glandular tissue. On CT, stones appear as white lesions against a gray background. The latest generation of MRI equipment, using T1-weighted and T2-weighted combination sequences, provides better sensitivity and stone contrast than the older-generation devices. Sialo-MRI is a technique used to identify the salivary ductal system without contrast, and it provides images similar to those obtained with sialography, but with less definition.

A comprehensive history and clinical examination are essential before any paraclinical examinations are carried out. The paraclinical examinations recommended before sialendoscopy are as follows:

A comprehensive history and clinical examination are essential before any paraclinical examinations are carried out. The paraclinical examinations recommended before sialendoscopy are as follows:

Ultrasound. The problem with ultrasound is that the accuracy of the results depends on the ultrasonographer’s level of expertise and that the stone location is not objectively visible for the sialendoscopist.

Ultrasound. The problem with ultrasound is that the accuracy of the results depends on the ultrasonographer’s level of expertise and that the stone location is not objectively visible for the sialendoscopist.

MRI. This is the most expensive method, and it provides poor definition or contrast between the stone and soft tissue. MRI should only be considered when the patient’s history suggests a diagnosis of stone but a calcified stone has not been diagnosed on CT.

MRI. This is the most expensive method, and it provides poor definition or contrast between the stone and soft tissue. MRI should only be considered when the patient’s history suggests a diagnosis of stone but a calcified stone has not been diagnosed on CT.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

CT scan without injection. This is currently the best imaging technique, as it provides all the necessary information needed by the sialendoscopist: number of stones, location, diameter, and sometimes ductal dilation. The method does expose the patient to radiation, but it is not dependent on the radiologist.

CT scan without injection. This is currently the best imaging technique, as it provides all the necessary information needed by the sialendoscopist: number of stones, location, diameter, and sometimes ductal dilation. The method does expose the patient to radiation, but it is not dependent on the radiologist.