CHAPTER 14 INFERIOR ALVEOLAR NERVE LATERALIZATION AND MENTAL NEUROVASCULAR DISTALIZATION

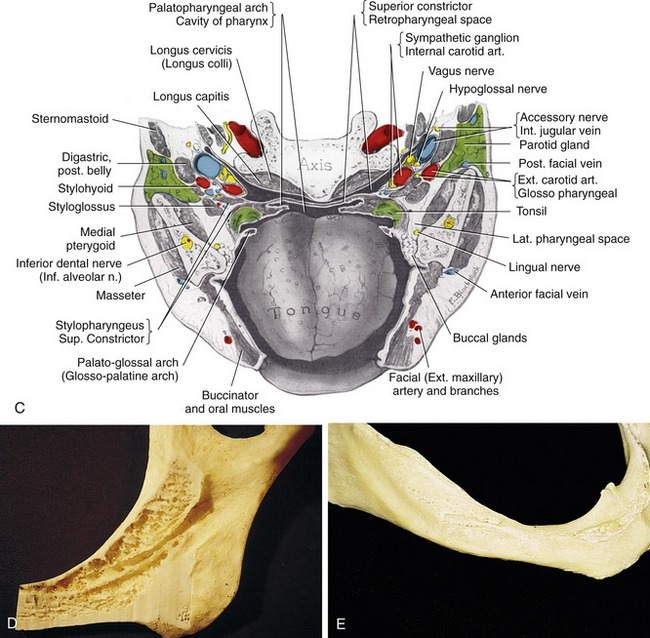

Since the development of endosteal implant reconstruction in the early 1960s, the severely atrophic posterior mandible has presented challenges for the implant reconstruction team. Most obviously, the presence of the inferior alveolar canal and its contents has required that the implant practitioner take precautions to avoid damaging the canal’s vital structures (Figures 14-1 and 14-2). One early solution was to surgically enter the posterior mandible, explore and isolate the inferior alveolar nerve and, in some instances, the mental neurovascular bundle, and relocate the nerve on a permanent or temporary basis as endosteal implants were simultaneously placed.1

Because of its technical difficulty, this reconstruction procedure was not widely used at first.2,3 In the past 10 years, however, it has begun to receive significant attention from various practitioners around the world.4–11 It still requires that the implant practitioner has complete familiarity with the specific anatomy (see Chapter 7) and the surgical handling of the neurovascular structures, even though technologic advancements have begun to facilitate nerve repositioning. With this consideration in mind, this chapter reviews the indications for and limitations of two related procedures: (1) inferior alveolar nerve lateralization, and (2) distalization of the mental neurovascular bundle. It also provides a detailed description of how the procedures are performed.12–14

Indications

Indications

Limitations

Limitations

Limiting factors include the following:

A higher degree of neurological deficiency is associated with distalization of the mental neurovascular bundle than with lateralization of the inferior alveolar nerve.11,13 An obvious reason for this difference in outcome is the fact that the surgical procedure for the former requires the use of high-speed or regular rotary instruments to circumvent completely the bone of the mental foramen from the buccal aspect of the mandible. Also, the incisive nerve that branches off from the mental nerve must be severed to mobilize the mental nerve and move it distally.15 Both factors require more manipulation and increase the risk of injury, therefore increasing postsurgical edema and potential complications.

Nerve Anatomy

Nerve Anatomy

Solar et al. and Ulm et al.16–30 documented the position and classification of the intraosseous path of the mental nerve. They reported the course of the mental nerve within the mandible as observed in 37 dried human specimens. Two types of pathways were documented. In 22 cases a siphon configuration was noted at the end of the mental canal and exit point. The investigators observed an arch that travels laterally and cranially. This area is wide, compared with the 4 to 5 mm before the exit of the foramen itself. This type of pathway was classified as Type I. A distance of up to 5 mm was measured between the mental foramen and the most anterior point (anterior loop) of the canal. No correlation was made between this distance and the degree of atrophy of the jaw.

In the other 15 of the 37 specimens, the mental canal was observed as ascending directly from the mandibular canal to the mental foramen without curving forward (i.e., no anterior loop). This type of pathway or course was classified as Type II. The average angle of inclination between the plane through which the mental canal (anterior loop) courses and the horizontal plane was measured at 50 degrees (Figure 14-4).

Preoperative Computed Tomographic Scans and Analysis

Preoperative Computed Tomographic Scans and Analysis

Regular radiographic studies, whether panoramic lateral cephalometric, occlusal, or periapical views, will not define a medial-lateral position of the inferior alveolar canal or mental foramen. They will only define the inferior-superior position as it relates to the residual crest of the ridge and the inferior border of the mandible.28,30–35

In some cases the nerve may be located significantly toward the medial or lateral cortical plates. This situation precludes the need to lateralize the neurovascular bundle during implant placement. In other words, the implant can be primarily placed medial or lateral to the canal without surgically repositioning these vital structures (Figure 14-5).36 A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan with three-dimensional reformatted images is recommended to define clearly the medial and lateral positions of the canal and foramen in all cases involving lateralization or distalization of these nerves.37

It is now possible to analyze these images by using SIM/Plant interactive software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Once the images are loaded into the computer, the nerve pathway and position can be defined easily and the neurovascular pathway can be highlighted in various colors (Figure 14-6, A and B). When the position and degree of the loop of the mental nerve and the position and pathway of the inferior alveolar nerve have been ascertained, the case can be planned with a high degree of accuracy. In addition, the computer can define the density, dimension, size, shape, and position of the bone and the number, size, and shape of planned implants (see Chapter 8 and Figure 14-6, C and D).12

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses