CHAPTER 10

Review of Spaces

Matthew W. Hearn,1 Christopher T. Vogel,2 Robert M. Laughlin,3 and Christopher J. Haggerty4

1Private Practice, Valparaiso, Indiana, USA

2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Missouri–Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri, USA

3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Naval Medical Base San Diego, San Diego, California, USA

4Private Practice, Lakewood Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Specialists, Lees Summit; and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri, USA

Never let the sun rise or set on pus.

—Matt Hearn

General Principles of Surgical Infection Management

- Incisions should be placed within non-involved skin and mucosa when possible. Incisions placed within necrotic or inflamed tissues result in delayed healing and unaesthetic scars.

- Incisions should be placed within aesthetic areas when possible. Incisions should parallel resting skin tension lines and should be placed within natural skin creases.

- Incisions should be placed to allow for gravity-dependent drainage when possible.

- Sharp dissection is recommended within the superficial layers only (skin, subcutaneous tissues, and mucosa). Blunt dissection is continued through the deeper layers to minimize damage to vital structures. Dissection patterns should parallel vessels and nerves to minimize iatrogenic damage to these structures.

- Each space should be explored completely to ensure complete disruption and evacuation of purulence and to avoid compartmentalization of the space.

- All explored spaces require drain placement. The exception is the peritonsillar space.

- Drains should be removed when they become nonproductive. Drains are removed based on the patient’s physical examination and drainage output. Drains are typically left in place for 72–120 hours. Nonproductive drains left in place for extended periods of time may lead to recontamination of the space.

- Wound margins are cleaned daily to remove blood clots, debris, and discharge.

Vestibular Space

Boundaries

- Superior: Buccinator muscle

- Inferior: Buccinator muscle

- Anterior: Intrinsic lip musculature

- Posterior: Buccinator muscle

- Lateral: Vestibular mucosa

- Medial: Mandible or maxilla with overlying periosteum

- Contents: Areolar connective tissue, parotid duct, long buccal, and mental nerves

- Connections: Canine (infraorbital) space and buccal space

- Signs and symptoms: Vestibular fluctuance

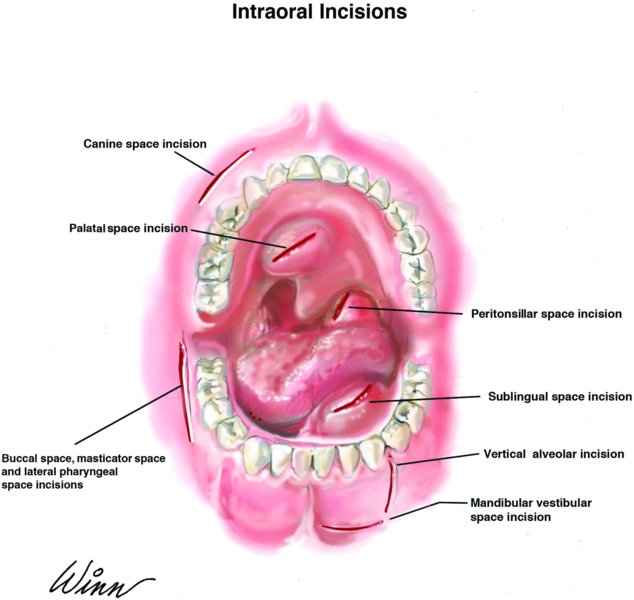

- Approach: Drainage is achieved via an incision parallel to and in the depth of the vestibule, ideally at the height of fluctuance. Blunt dissection is utilized to explore the vestibular space. Vertical incisions are utilized in the region of the mental foramen to avoid injury to the mental nerve (Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. Intraoral drainage incision sites.

Key Points

The vestibular space is a potential space between the vestibular mucosa and the underlying muscles of facial expression.

Buccal Space (Buccinator Space)

Boundaries

- Superior: Zygomatic arch

- Inferior: Lower border of the mandible

- Anterior: Labial musculature (zygomatic and depressor muscles at the angle of the mouth)

- Posterior: Pterygomandibular raphe

- Lateral: Skin of the cheek

- Medial: Buccinator muscle and the overlying buccopharyngeal fascia

- Contents: Buccal fat pad, Stensen’s duct, transverse facial artery and vein, and the anterior facial artery and vein

- Connections: Canine space, submandibular space, masticator space, and infratemporal space

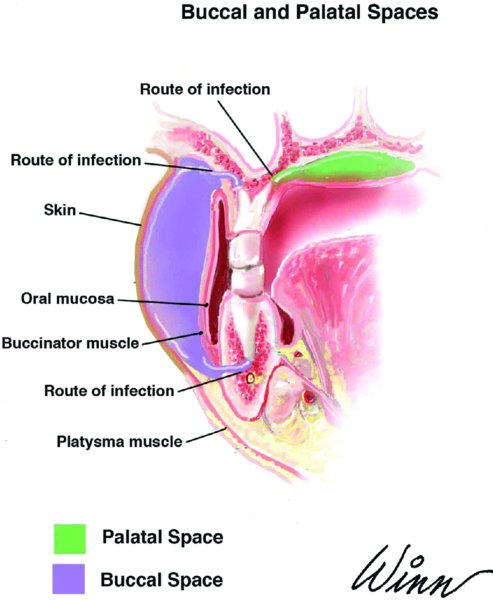

- Signs and symptoms: Cheek edema (Figure 10.2)

- Approach: The buccal space may be drained intraorally or extraorally. Intraoral drainage is best accomplished via a mandibular or maxillary vestibular incision with dissection through the buccinator muscle (Figure 10.1). Extraoral drainage is achieved via a submandibular incision (Figure 10.3). Blunt dissection is directed superiorly and superficial to the buccinator muscle to enter the buccal space (Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.2. Typical presentation of a buccal space abscess with marked cheek edema anterior to the masseter.

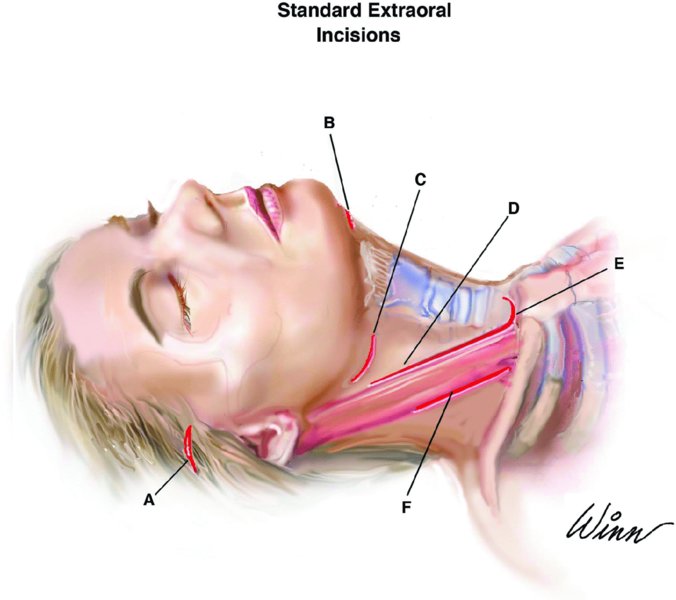

Figure 10.3. (A) Gillies incision; (B) submental incision; (C) submandibular incision; (D) anterior sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) incision; (E) transcervical mediastinum incision; and (F) posterior SCM incision.

Figure 10.4. Anatomy of the buccal and palatal spaces.

Key Points

- Isolated buccal space abscesses do not cause trismus. Trismus, in the presence of a buccal space abscess, is an important and ominous finding that should alert the clinician to the posterior spread of infection.

- In the pediatric population (age 3 months–3 years), it is important to differentiate between a true buccal space abscess of odontogenic origin and from Haemophilus influenzae cellulitis.

Palatal Space

Boundaries

- Superior: Palate

- Inferior: Periosteum

- Anterior: Alveolar process of the maxilla

- Posterior: Periosteal attachment to the palate and the maxilla

- Lateral: Maxillary alveolus

- Medial: Midline space (however, abscesses are typically contained laterally due to firm periosteal attachment)

- Contents: Greater palatine nerve, artery, and vein, and nasopalatine nerve

- Connections: None

- Signs and symptoms: Localized palatal swelling

- Approach: Drainage is achieved via an incision through palatal mucosa into the abscess cavity that parallels the regional vasculature, in particular the greater palatine neurovascular bundle (Figure 10.1).

Key Points

Palatal space infections typically arise from the palatal roots of maxillary molars and premolars (Figure 10.3).

Canine Space (Infraorbital Space)

Boundaries

- Superior: Infraorbital rim

- Inferior: Oral mucosa

- Anterior: Quadratus labii superioris muscles (levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, levator labii superioris, zygomaticus minor, and zygomaticus major)

- Posterior: Levator anguli oris (caninus) muscle

- Lateral: Buccal space

- Medial: Nasal cartilages and subcutaneous tissue

- Contents: Angular artery and vein and the infraorbital nerve

- Connections: Vestibular space and buccal space

- Signs and symptoms: Obliteration of the nasolabial fold and periorbital edema

- Approach: Intraoral drainage is accomplished via an incision located within the depth of the vestibule, immediately adjacent to the abscessed tooth (Figure 10.1). Blunt dissection is carried superiorly through the levator anguli oris (caninus) muscle and into the canine space.

Key Points

- Canine space infections typically arise when an anterior maxillary periapical abscess (typically from a canine) erodes through the buccal plate superior to the attachment of the caninus muscle.

- Care must be taken to avoid damage to the infraorbital nerve during exploration of the canine space.

- The facial veins are generally valveless (allowing bidirectional flow). Infections of the canine space can result in septic thrombophlebitis or emboli of the angular vein. Cavernous venous sinus thrombosis can result from ascension from the angular vein, to the inferior ophthalmic vein, and into the cavernous sinus. Prompt and aggressive treatment of canine space infections are necessary to avoid this exceeding rare, but potentially devastating sequela.

Submental Space

Boundaries

- Superior: Mylohyoid muscle

- Inferior: Superficial (investing) layer of the deep cervical fascia

- Anterior: Inferior border of the mandible

- Posterior: Hyoid bone

- Lateral: Anterior bellies of the digastric muscles

- Medial: No true medial border as it is a midline space

- Contents: Anterior jugular veins and lymph nodes

- Connections: Submandibular space

- Signs and symptoms: Submental edema and erythema (Figure 10.5)

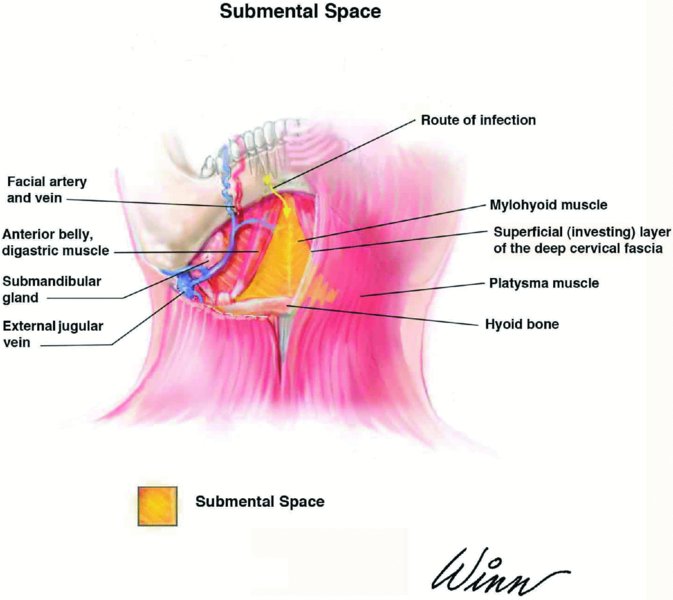

- Approach: Drainage is accomplished via a horizontal midline incision just anterior to the hyoid bone within the submental skin crease (Figure 10.3). Incisions placed near the hyoid bone provide gravity dependent drainage as the hyoid bone is the most inferior boundary of the submental space (Figure 10.6). Blunt dissection is directed superiorly through skin, subcutaneous tissue, and the platysma muscle to enter the submental space. Care must be taken to avoid the anterior jugular veins. The submental space may also be drained intraorally via a vestibular incision continued through the mentalis muscle. The intraoral approach fails to provide dependent drainage.

Figure 10.5. Typical submental abscess presentation with obvious edema and erythema of the submental region. Prior to surgical drainage, a sterile aspirate is obtained for culture and sensitivity.

Figure 10.6. Anatomy of the submental space.

Key Points

- The submental space is commonly involved via medial extension of submandibular space infections. Other potential sources of infection include direct spread from the mandibular incisors and symphyseal fractures.

- The spread of infection from the submental space posterolateral to the anterior digastric muscles allows for direct bilateral extension of infections to the submandibular and sublingual spaces. Bilateral brawny cellulitis of the submental, sublingual, and submandibular spaces is termed Ludwig’s angina.

Submandibular Space (Submaxillary Space, Submylohyoid Space)

Boundaries

- Superior: Inferior and lingual surfaces of the mandible and the mylohyoid muscle

- Inferior: Investing fascia with the digastric tendon at the apex

- Anterior: Anterior belly of the digastric muscle

- Posterior: Posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the stylohyoid muscle

- Lateral: Platysma muscle and investing fascia

- Medial: Hyoglossus and mylohyoid muscles

- Contents: Facial artery and vein, marginal mandibular nerve, mylohyoid nerve, submandibular gland, and lymph nodes

- Connections: Lateral pharyngeal space, submental space, sublingual space, and buccal space

- Signs and symptoms: Swelling at the inferior border of the mandible that extends medially to the anterior digastric muscle and posteriorly to the hyoid bone

- Approach: Drainage is accomplished via an extraoral submandibular approach (Figure 10.3). A 2–4 cm incision is placed 2–3 cm caudal to the inferior border of the mandible, parallel to the resting skin tension lines at the level of the hyoid bone and at the point that will allow for maximum gravity-dependent drainage (see Figure 10.10 in Case Report 10.1). A hemostat is introduced through the skin incision and is directed toward the inferior border of the mandible. The hemostat is then directed lingual to the mandible to enter the submandibular space. Blunt dissection continues superiorly along the lingual aspect of the body of the mandible and is continued superiorly to the mylohyoid muscle.

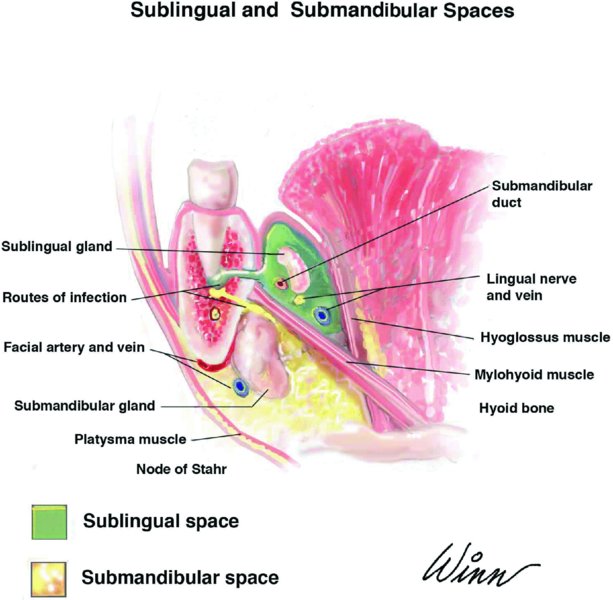

Figure 10.7. Anatomy of the sublingual and submandibular spaces.

Figure 10.8. Coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan demonstrating a combined submandibular-sublingual space abscess.

Figure 10.9. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan demonstrating a combined submandibular-sublingual space abscess.

Figure 10.10. The incision is marked caudal to the inferior border of the mandible, parallel to the resting skin tension lines, at the level of the hyoid bone, and in an area that will allow for maximum dependent drainage.

Key Points

The submandibular approach provides extraoral access to the sublingual, submandibular, buccal, masticator (pterygomandibular and masseteric), and lateral pharyngeal spaces.

Sublingual Space

Boundaries

- Superior: Oral mucosa of the floor of the mouth

- Inferior: Mylohyoid muscle

- Anterior: Mandible

- Posterior: Open

- Lateral: Lingual cortex of the mandible

- Medial: Muscles of the tongue

- Contents: Sublingual gland, lingual nerve, Wharton’s duct, hypoglossal nerve, and the sublingual artery and vein

- Connections: Submandibular space and the lateral pharyngeal space

- Signs and symptoms: Floor of the mouth and tongue elevation, dysphasia, and sialorrhea

- Approach: Drainage is best accomplished via an extraoral submandibular approach (Figure 10.3). Once the submandibular space is explored, blunt dissection continues superiorly along the lingual aspect of the body of the mandible and is continued through the mylohyoid muscle to enter the sublingual space. Nondependent drainage can be achieved via an intraoral incision placed at the anterior and lateral portion of the floor of the mouth, parallel and lateral to the submandibular duct (Figure 10.1). Blunt dissection proceeds through the oral mucosa and directly into the sublingual space.

Key Points

- Infections of the sublingual space are typically odontogenic in origin. Whether an odontogenic infection occurs within the sublingual space or the submandibular space is a result of the spread of the infection in relation to the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle (Figure 10.7). Infections originating superior to the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle (teeth anterior to the second molar) will occur within the sublingual space. Infections originating inferior to the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle (second and third molars) will present within the submandibular space.

- Posteriorly, the sublingual space is contiguous with the submandibular space, allowing for rapid spread of infection.

Figure 10.11. Purulence is expressed once the submandibular space is entered.

Figure 10.12. Blunt finger dissection is utilized to ensure that the entire submandibular and sublingual spaces have been explored.

Figure 10.13. Drain placement within the right submandibular, sublingual, and lateral pharyngeal spaces.

Masticator Space (Masticatory Space, Masseter–Mandibulopterygoid Space)

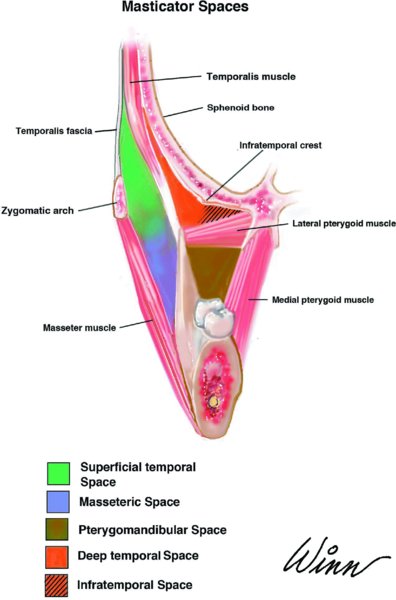

The masticator space consists of four subspaces:

- Masseteric (submasseteric) space

- Pterygomandibular space

- Superficial temporal space

- Deep temporal space

Boundaries

- Superior: Temporal crest

- Inferior: Pterygomasseteric sling and the inferior border of the mandible

- Anterior: Orbital rim and the anterior border of the ramus

- Posterior: Posterior border of the mandible

- Lateral: Parotideomasseteric fascia (superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia)

- Medial: The greater wing of the sphenoid bone, the squamous portion of the temporal bone, and the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia deep to the medial pterygoid

- Contents: Muscles of mastication (temporalis, masseter, medial, and lateral pterygoids), internal maxillary artery, mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, and the buccal fat pad

- Connections: All subspaces are interconnected (Figure 10.14). Connections also exist between the buccal, lateral pharyngeal, and infratemporal spaces.

- Signs and symptoms: Trismus and edema

Figure 10.14. Anatomy of the masticator space.

Key Points

- The masticator space contains the masseteric (submasseteric), pterygomandibular, deep, and superficial temporal spaces (Figure 10.14).

- Individual subspaces will be discussed in detail in the following four subsections.

Masseteric (Submasseteric) Space

Boundaries

- Superior: Zygomatic arch

- Inferior: Inferior border of the mandible

- Anterior: Anterior border of the ramus

- Posterior: Posterior border of the ramus

- Lateral: Parotideomasseteric fascia (superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia)

- Medial: Vertical ramus of the mandible

- Contents: Masseter muscle, masseteric artery, and vein

- Connections: Superficial temporal space and pterygomandibular space

- Signs and symptoms: Trismus and posterior mandibular angle edema

- Approach: Drainage is best accomplished via an extraoral submandibular approach to allow for gravity dependent drainage (Figure 10.3). After entering the submandibular space, blunt dissection is continued posteriorly through the pterygomasseteric sling to enter the masseteric space located between the body of the masseter and the lateral ramus of the mandible. Alternatively, the masseteric space may be accessed intraorally (Figure 10.1) via a vertical incision lateral and parallel to the pterygomandibular raphe. Sharp dissection is carried through the buccinator muscle, and blunt dissection is continued to enter the masseteric space.

Key Points

- Common sources of infection include pericoronitis, third molar abscesses, and mandibular angle fractures.

- The intraoral approach is often impractical due to the presence of trismus and the inability to establish dependent drainage.

Pterygomandibular Space

Boundaries

- Superior: Lateral pterygoid muscle

- Inferior: Pterygomasseteric sling

- Anterior: Anterior border of the ramus

- Posterior: Posterior border of the ramus

- Lateral: Ascending ramus

- Medial: Superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia

- Contents: Inferior alveolar artery, vein, and nerve; lingual and mylohyoid nerves

- Connections: Masseteric space, infratemporal space, and lateral pharyngeal space

- Signs and symptoms: Trismus

- Approach: Extraoral drainage is accomplished via a submandibular approach (Figure 10.3). Once the inferior border of the mandible is reached, blunt dissection proceeds posteriorly through the pterygomasseteric sling to enter the pterygomandibular space located between the body of the medial pterygoid muscle and the medial ramus of the mandible. Intraorally, the space may be accessed through an incision placed lateral and parallel to the pterygomandibular raphe through the buccinator muscle (Figure 10.1). Blunt dissection is carried into the pterygomandibular space on the medial side of the mandible. In addition, the intraoral approach may be carried inferiorly through the pterygomandibular space, passing through the pterygomasseteric sling into the submandibular space. This may then be connected to a submandibular approach, and a through-and-through intraoral-extraoral drain can be passed with resulting gravity-dependent drainage.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses